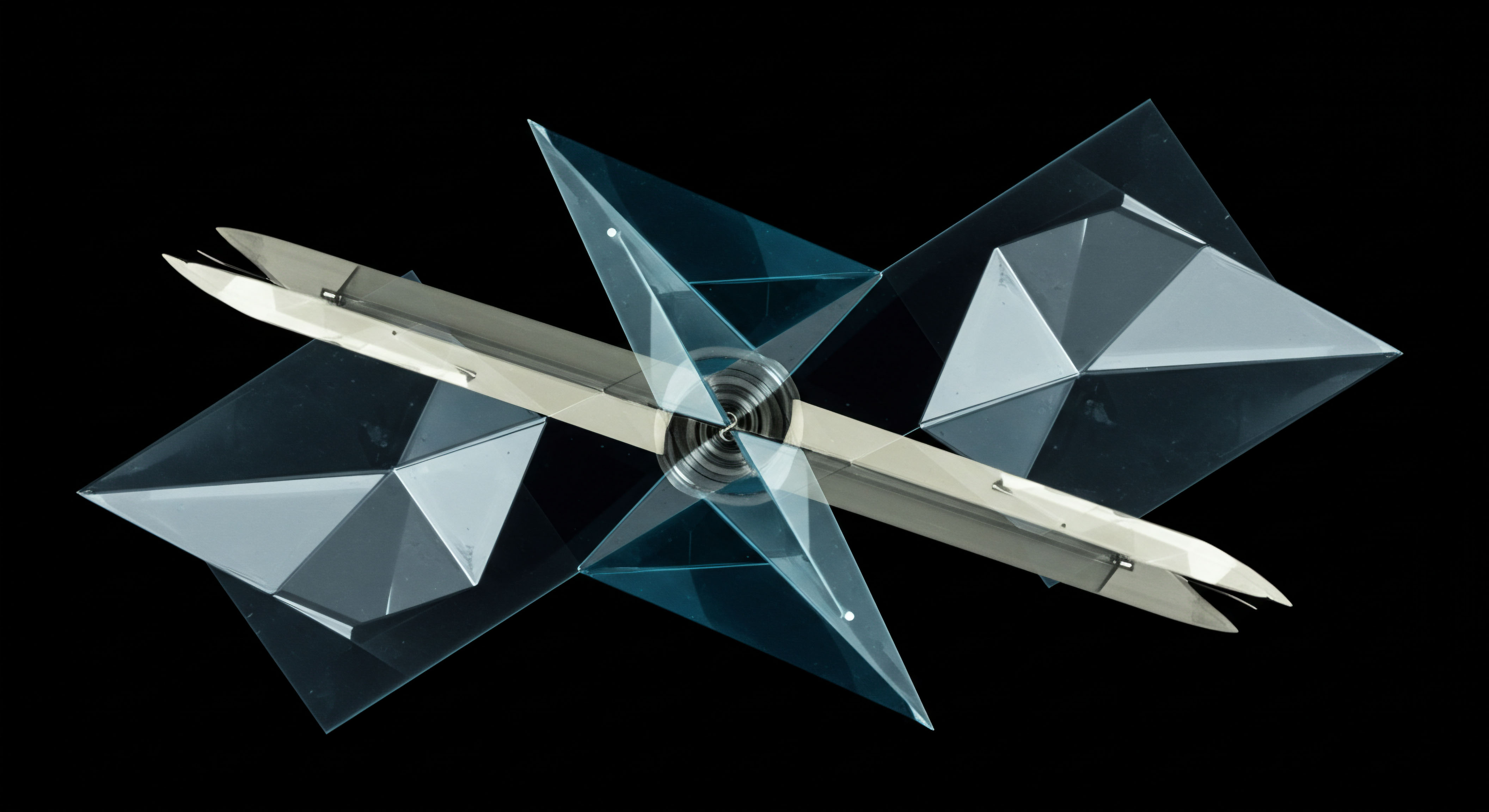

The Market as a System of Spreads

Financial markets are systems of distributed information. Prices for the same asset across different venues represent distinct moments in the price discovery process. An inter-exchange spread is the differential between the price of a single asset on two separate exchanges. This condition arises from the natural fragmentation of liquidity in global markets.

Every exchange possesses its own unique order book, with its own depth of supply and demand, leading to temporary and persistent pricing dislocations. These are not market flaws; they are fundamental characteristics of its structure.

Understanding this structure is the first step toward operating within it professionally. The price of an asset on one exchange versus another is a reflection of that venue’s immediate liquidity and order flow. A temporary surge in buying activity on one platform will create a momentary price deviation from the global average. Capturing the value of these deviations is the entire discipline of spread trading.

It is a systematic process designed to extract returns from the market’s inherent structural dynamics. The goal is to identify these price gaps and execute trades to profit from the difference as they converge.

This approach treats the market as a landscape of opportunities defined by price relationships. Different types of spreads exist, including those between related assets or contracts with different expiry dates, but the inter-exchange spread is the most direct expression of spatial arbitrage. It capitalizes on price differences for the identical asset, making it a pure play on market infrastructure. The existence of a spread indicates a momentary inefficiency and an opportunity for price convergence.

A trader’s objective is to position their portfolio to benefit from this convergence. The strategy is built upon the principle that, over time, arbitrage forces will cause these dislocated prices to realign. Success in this domain requires a perspective that views the market not as a single entity, but as a network of interconnected liquidity pools, each with its own micro-dynamics.

The Arbitrage Mechanic in Practice

Profiting from inter-exchange spreads requires a defined operational framework. The core mechanic involves the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same asset on two different exchanges to capture the existing price gap. This is a market-neutral approach, as the position is hedged against overall market direction.

The profit is generated from the spread itself, not from a directional bet on the asset’s price movement. This section details the protocols for executing these strategies with precision.

Strategy One the Direct Inter-Exchange Arbitrage

The most straightforward application of this concept is direct arbitrage. This involves identifying a cryptocurrency trading at a lower price on one exchange and a higher price on another, then executing opposing trades to capture the difference. This strategy’s effectiveness is contingent on speed and preparation, as these opportunities can be fleeting.

Execution Protocol

A successful execution requires having assets positioned correctly before a trade is initiated. The latency involved in moving capital between exchanges makes it impossible to react to a spread by first sending funds. A parallel trading strategy is the professional standard, where a trader holds capital on multiple exchanges simultaneously. This preparedness allows for immediate action when a profitable spread is identified.

- Asset Allocation ▴ You must maintain inventories of both the asset you wish to trade (e.g. Bitcoin) and the quote currency (e.g. USDT) on at least two separate exchanges. For example, hold both BTC and USDT on Exchange A and Exchange B.

- Spread Identification ▴ Constantly monitor the price of your target asset across both exchanges. An opportunity exists when the bid price on one exchange is higher than the ask price on the other, after accounting for all trading fees.

- Simultaneous Execution ▴ When a profitable spread is found, you execute two trades at once. You would sell the asset on the exchange where the price is higher and buy the same amount of the asset on the exchange where the price is lower. For instance, sell 1 BTC on Exchange A for $70,100 while simultaneously buying 1 BTC on Exchange B for $70,000.

- Position Realignment ▴ After the trade, your inventory will be skewed. You will have more USDT on Exchange A and more BTC on Exchange B. Periodically, you will need to rebalance these holdings, which may involve transferring assets between venues during periods of low market volatility.

Risk Parameters

The primary risks in direct arbitrage are related to execution. Slippage can occur if the price moves between the moment you identify the spread and the moment your trades are filled. This is particularly relevant in volatile or illiquid markets.

Additionally, trading fees on both exchanges must be factored into every calculation to ensure the spread is genuinely profitable. A failure to account for fees can turn an apparent profit into a net loss.

A tight spread in a highly liquid market means that the cryptocurrency is in high demand, allowing for quick trades that are close to the market price.

Strategy Two the Basis Spread

A more structured method for trading spreads involves using futures contracts. Basis trading is an arbitrage strategy that captures the difference between the spot price of an asset and its futures price. This “basis” is a quantifiable spread that tends to converge as the futures contract approaches its expiration date. This strategy allows traders to lock in a defined profit over a set period.

The Market Neutral Position

This protocol creates a position that is delta neutral, meaning it is insulated from directional price movements. The profit is derived purely from the convergence of the spot and futures prices. For example, a trader might buy Bitcoin in the spot market while simultaneously selling a Bitcoin futures contract on a different exchange. If the futures contract is priced higher than the spot price, the trader has locked in the difference, which will be realized upon the contract’s settlement.

Consider a scenario where Bitcoin trades at $80,000 on a spot exchange, while a three-month futures contract on another exchange trades at $82,000. A trader could buy 1 BTC on the spot market and sell one futures contract. The $2,000 difference is the basis.

When the contract expires, the futures price and the spot price will converge. The trader delivers the asset at the agreed-upon futures price, realizing the $2,000 gain regardless of whether Bitcoin’s price went up or down in the interim.

Managing Convergence and Funding Rates

The basis is not static; it fluctuates over time due to changes in market sentiment, interest rates, and supply and demand dynamics. This fluctuation creates “basis risk” ▴ the risk that the spread could narrow or widen unexpectedly. However, for physically settled futures, the price of the future and the price of the underlying asset must converge at expiration.

In the case of perpetual futures, which do not have an expiration date, the mechanism that tethers the futures price to the spot price is the funding rate. When the perpetual contract trades at a premium to the spot price, longs pay shorts a funding fee, incentivizing traders to sell the perpetual and buy the spot, which in turn helps to close the spread. A basis trading strategy using perpetual futures can be designed to consistently collect these funding payments as a source of income, while remaining hedged against directional price risk.

Automating the Capture

The opportunities for inter-exchange spreads, particularly the most profitable ones, are often short-lived. Manual execution is frequently too slow to capture them effectively. Professional traders and firms utilize automated trading systems, often connecting directly to exchange APIs, to monitor prices and execute trades in milliseconds.

These systems can track hundreds of asset pairs across dozens of exchanges simultaneously, acting on opportunities far faster than a human operator could. Building or gaining access to such infrastructure is a key component of scaling these strategies from occasional trades into a consistent source of returns.

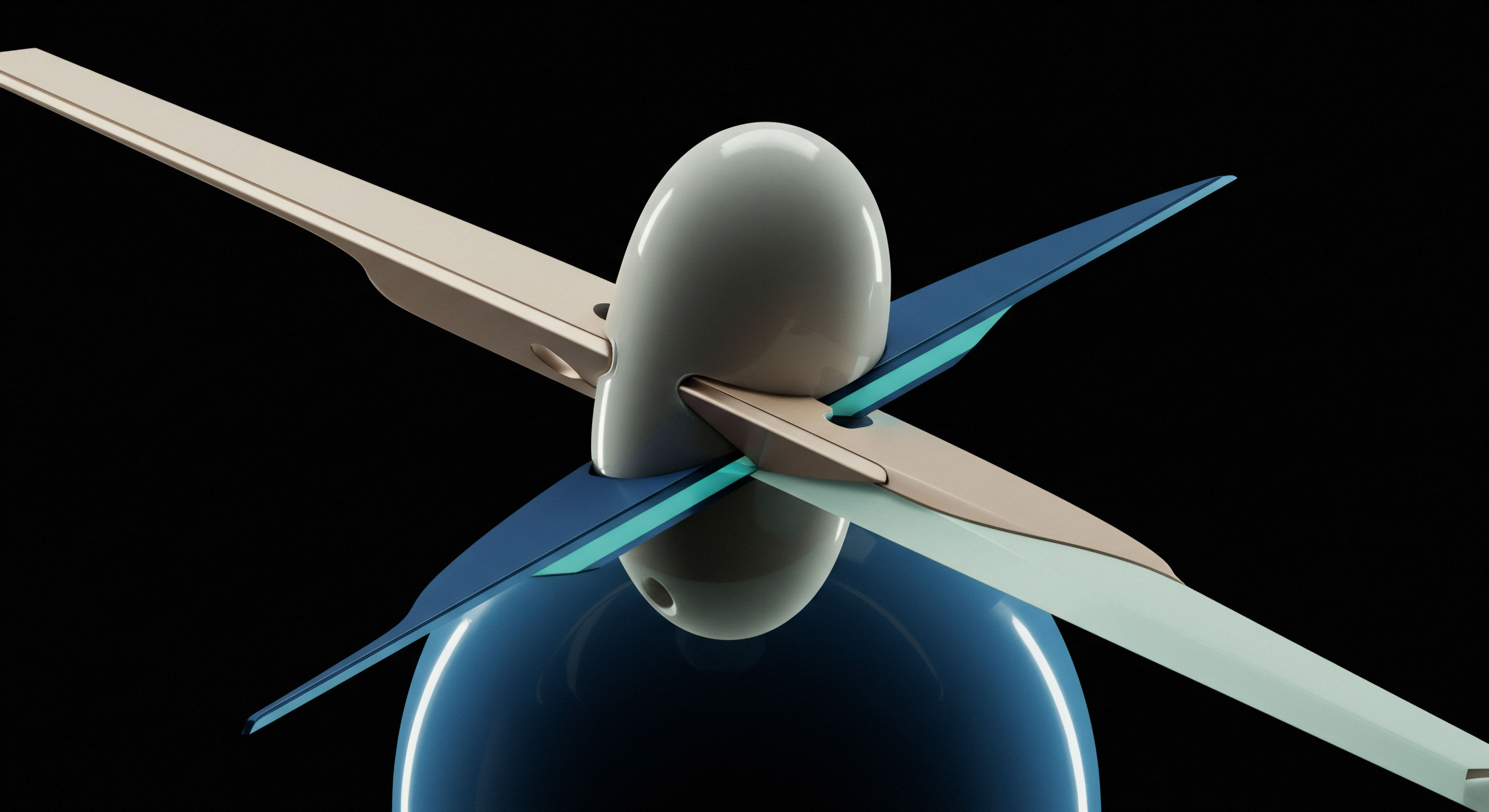

From Trades to a Systemic Return Engine

Mastering the mechanics of spread trading is the foundation. The next stage of development involves integrating these techniques into a broader portfolio strategy. This means moving beyond capturing individual spreads and architecting a system for continuous alpha generation. The focus shifts from single-trade profitability to building a diversified, resilient portfolio of market-neutral strategies that perform across varied market conditions.

Building a Diversified Spread Portfolio

Relying on a single asset pair on two exchanges introduces concentration risk. A more robust approach involves diversifying across multiple dimensions. This includes trading a variety of cryptocurrencies, as different assets will present opportunities at different times. It also means establishing a presence on a wide array of exchanges, from major centralized venues to more specialized platforms.

This diversification mitigates the risk of a single point of failure, such as an exchange going offline or a particular asset’s liquidity drying up. The result is a portfolio of many small, uncorrelated spread trades, which collectively can produce a smoother and more consistent return profile.

Advanced Risk the Basis Risk Component

While basis trading is market-neutral, it contains its own unique risk profile. Basis risk is the potential for the spread between the spot and futures price to move unfavorably after a position has been established. For instance, if you are long the basis (long spot, short futures), you profit as the basis narrows. If the basis widens instead, your position will show an unrealized loss.

Understanding the factors that drive the basis, such as shifts in carrying costs or changes in market sentiment, is critical. Managing this risk involves setting clear parameters for how much basis fluctuation you are willing to tolerate and potentially using options or other derivatives to hedge the basis itself.

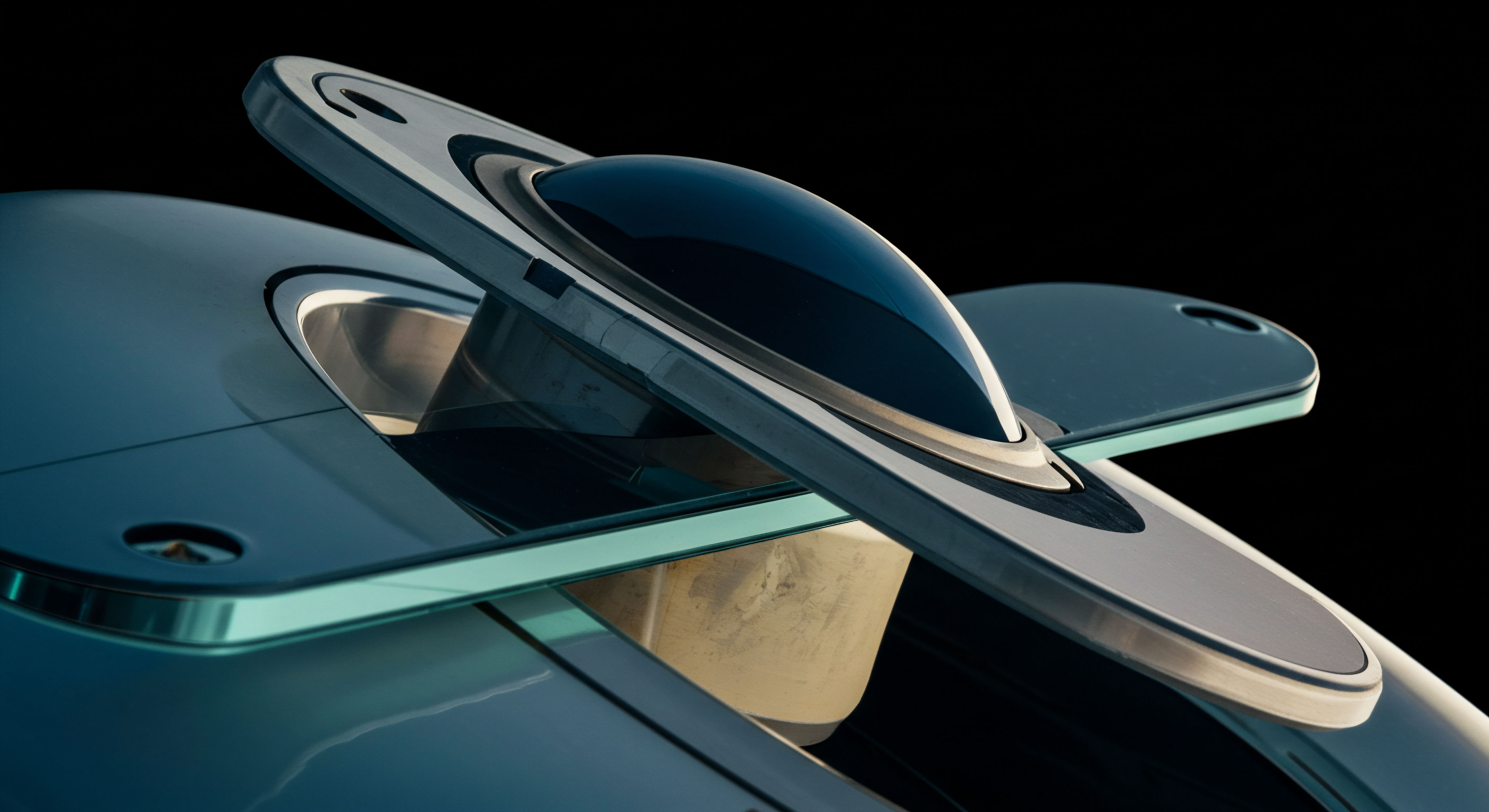

The Macro View Market Structure as an Asset

At the highest level of sophistication, a trader of inter-exchange spreads is not merely trading assets. They are trading the market’s structure itself. The portfolio’s performance becomes a function of systemic inefficiencies like liquidity fragmentation and the price discovery process. This perspective reframes the entire endeavor.

You are capitalizing on the predictable frictions within the global trading system. Your ‘asset’ is the persistent, quantifiable inefficiency that exists between different liquidity pools. This is a profound shift in mindset, from participating in the market to engineering a system that profits from the way the market operates. It requires a deep understanding of market microstructure, including order book dynamics, the impact of large trades, and the flow of information between different trading venues.

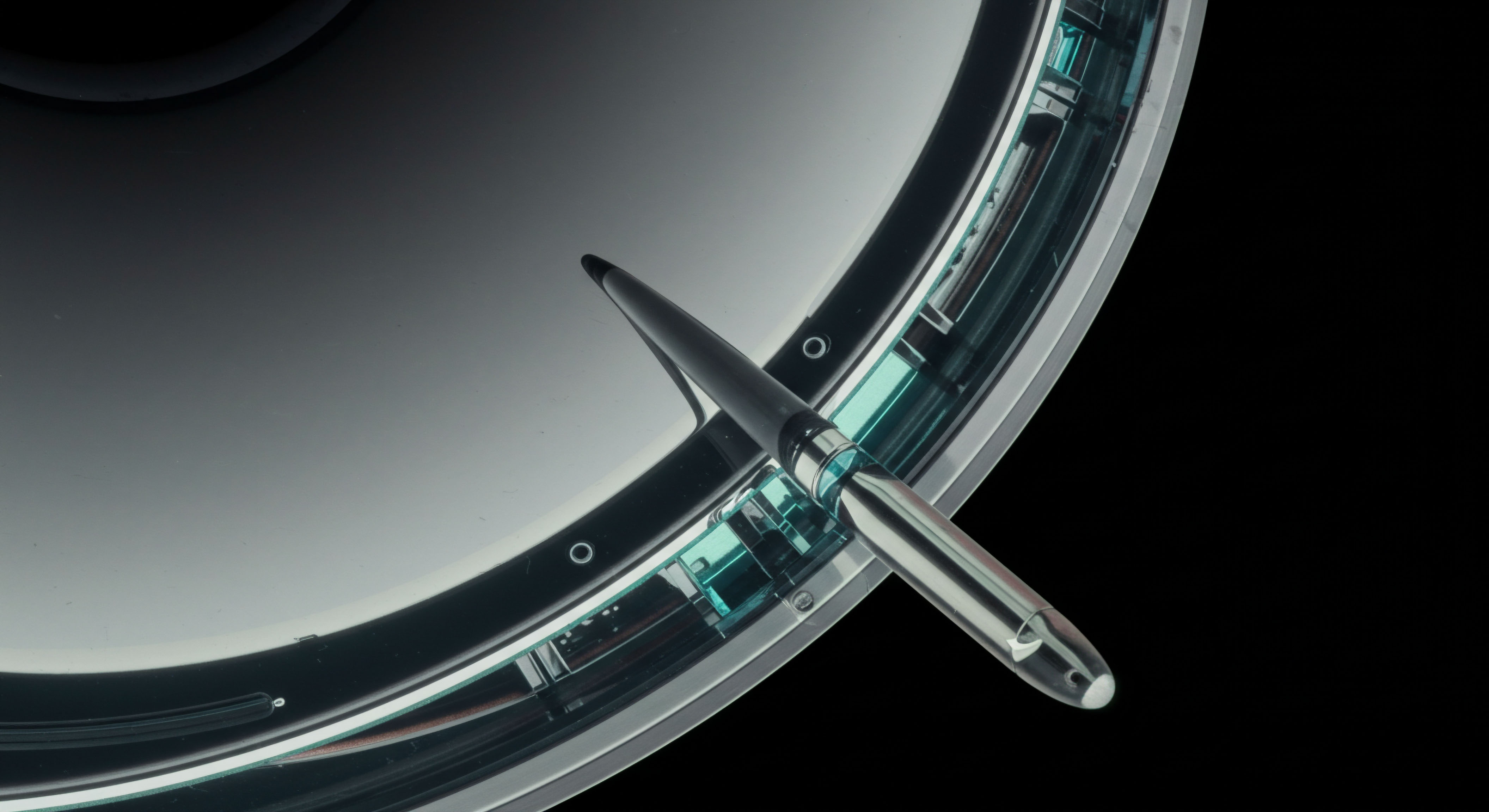

The Engineer’s Approach to the Market

You have moved beyond the conventional view of market participation. The price of an asset is no longer a single data point, but a spectrum of possibilities distributed across a global network. By learning to see the spreads between these points, you have gained access to a new dimension of strategic operation. This is the work of a market engineer, one who constructs a return profile from the very architecture of modern finance.

The path forward is one of continuous refinement, of sharpening your execution protocols and deepening your understanding of the market’s intricate machinery. Your portfolio is now a reflection of this systemic insight.

Glossary

Inter-Exchange Spread

Price Discovery

Supply and Demand

Parallel Trading

Futures Contract

Futures Price

Delta Neutral

Basis Risk

Basis Trading

Liquidity Fragmentation