Concept

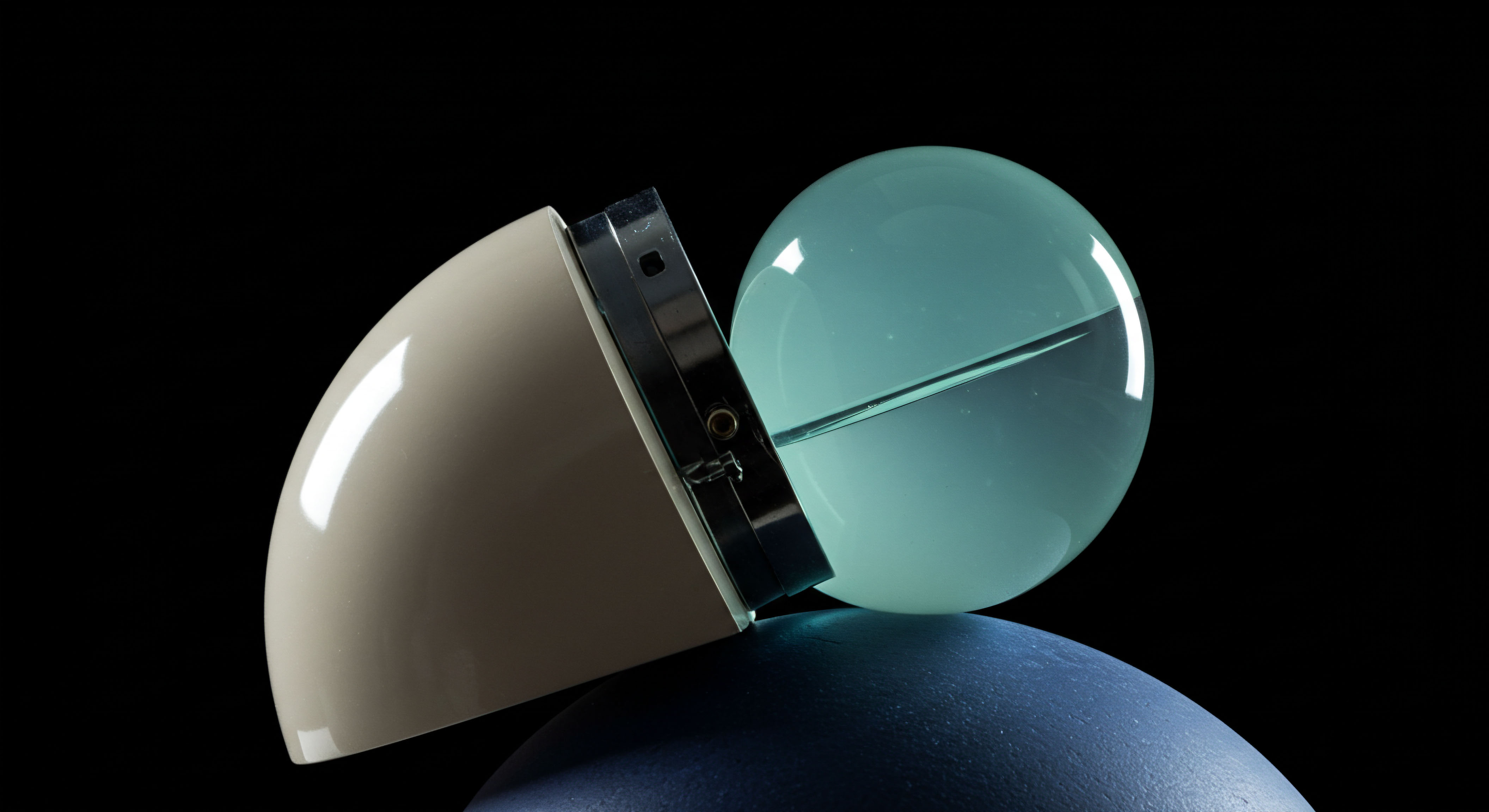

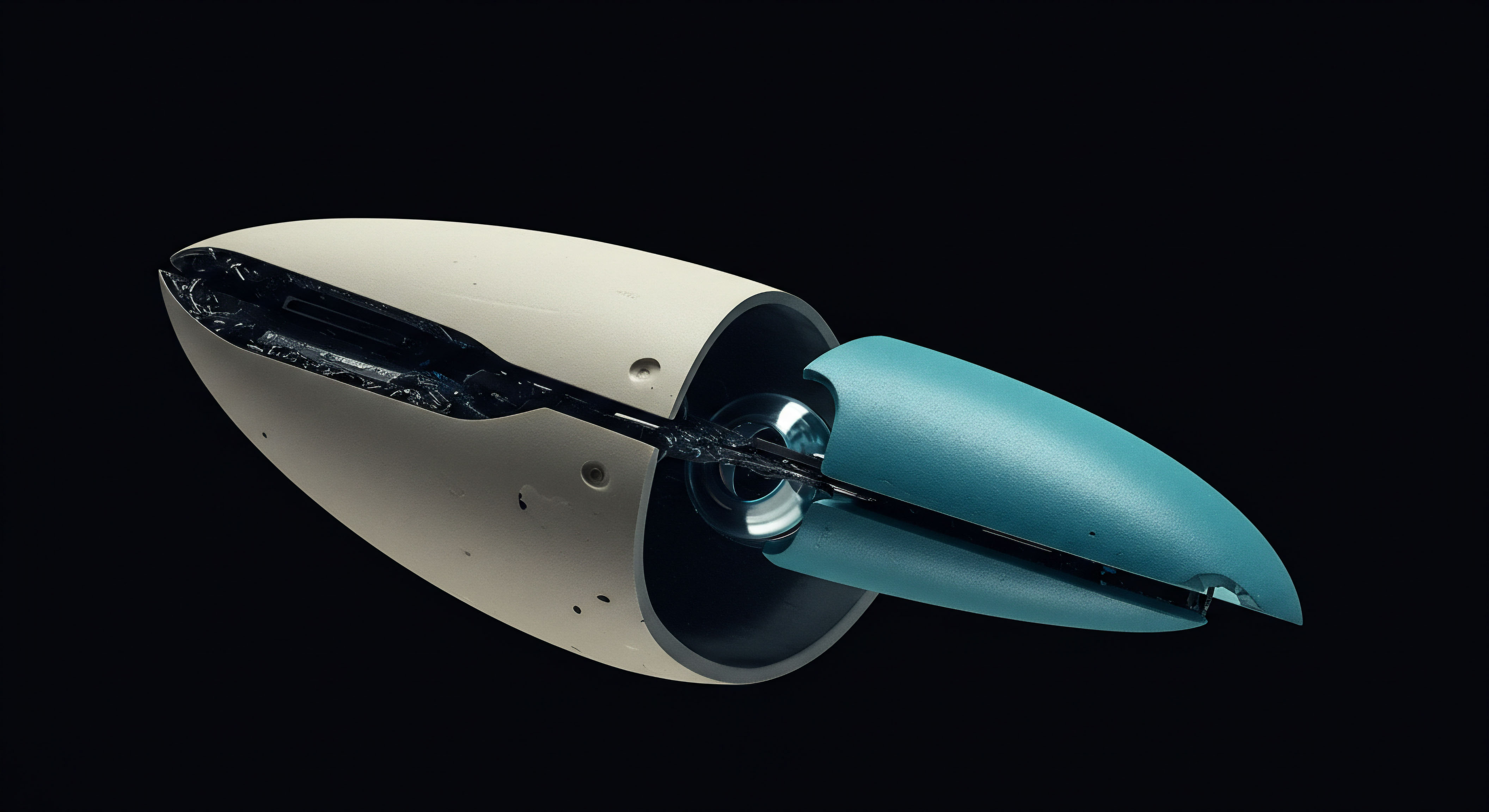

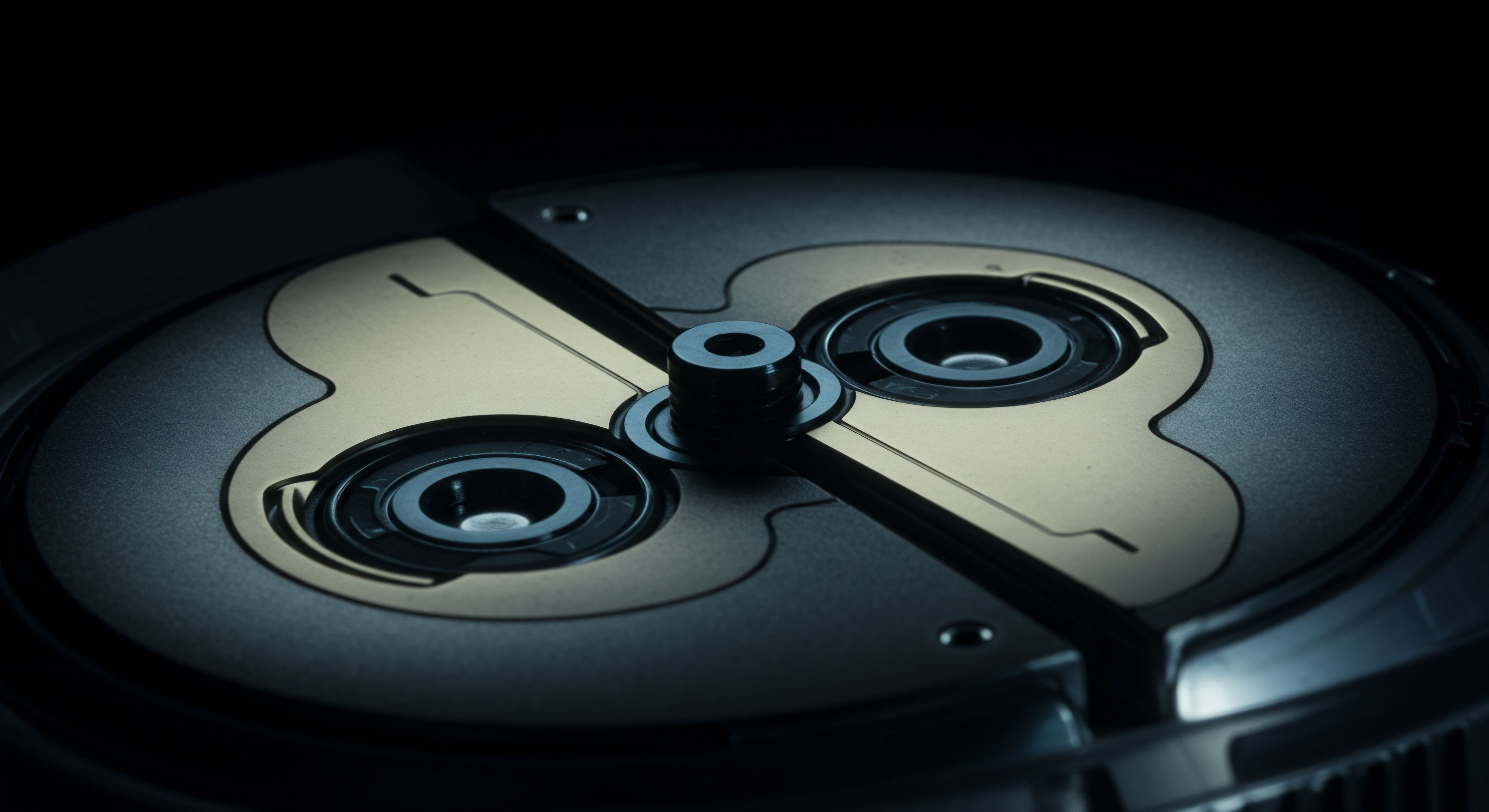

The question of achieving a unified global regulatory framework for crypto assets is frequently presented as a political challenge, a matter of aligning the divergent interests of sovereign nations. This perspective, while valid, overlooks a more fundamental systemic conflict. The core issue resides in the collision of two distinct architectural philosophies ▴ the decentralized, cryptographically-secured design of digital assets and the centralized, jurisdictionally-bound structure of traditional financial oversight.

A unified framework is therefore not simply a matter of agreeing on rules; it requires reconciling these opposing operational paradigms. For the institutional participant, understanding this foundational tension is the first step toward constructing a resilient operational posture in an environment defined by regulatory fragmentation.

Digital assets operate on principles of disintermediation and borderless value transfer, their integrity upheld by distributed consensus mechanisms rather than by a central authoritative body. This architecture is inherently global and indifferent to the geographic location of its participants. In stark contrast, financial regulation is the quintessential expression of national sovereignty. It is built upon a system of geographically-demarcated perimeters, with central banks, securities commissions, and financial intelligence units acting as gatekeepers for their respective economies.

Each regulatory body enforces rules tailored to its specific mandate, be it monetary stability, investor protection, or the prevention of illicit finance. The result is a patchwork of national and regional legal systems that are, by design, unequipped to supervise a technology that transcends their borders effortlessly.

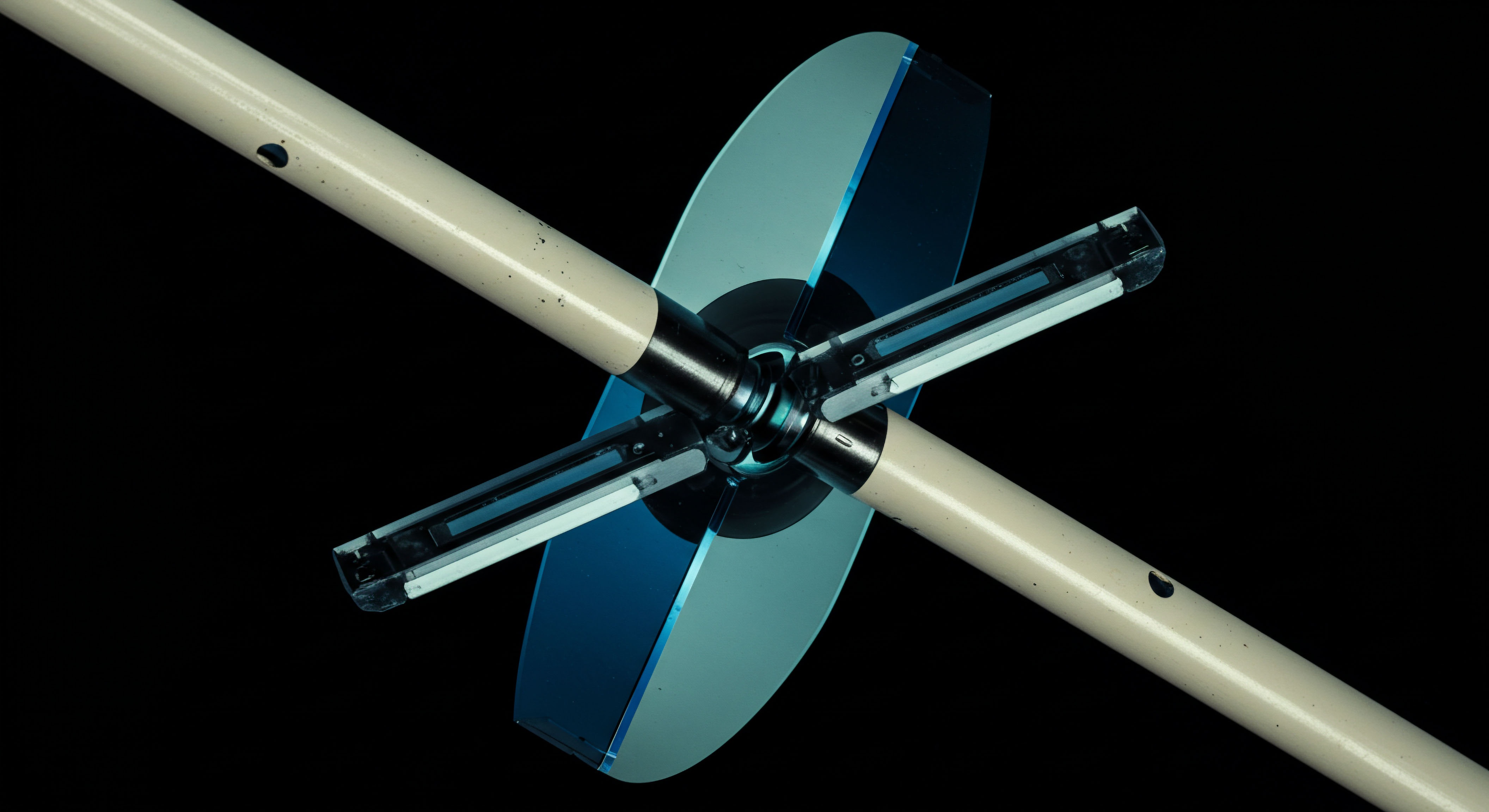

A globally unified regulatory system for crypto assets confronts the architectural mismatch between decentralized technology and centralized national oversight.

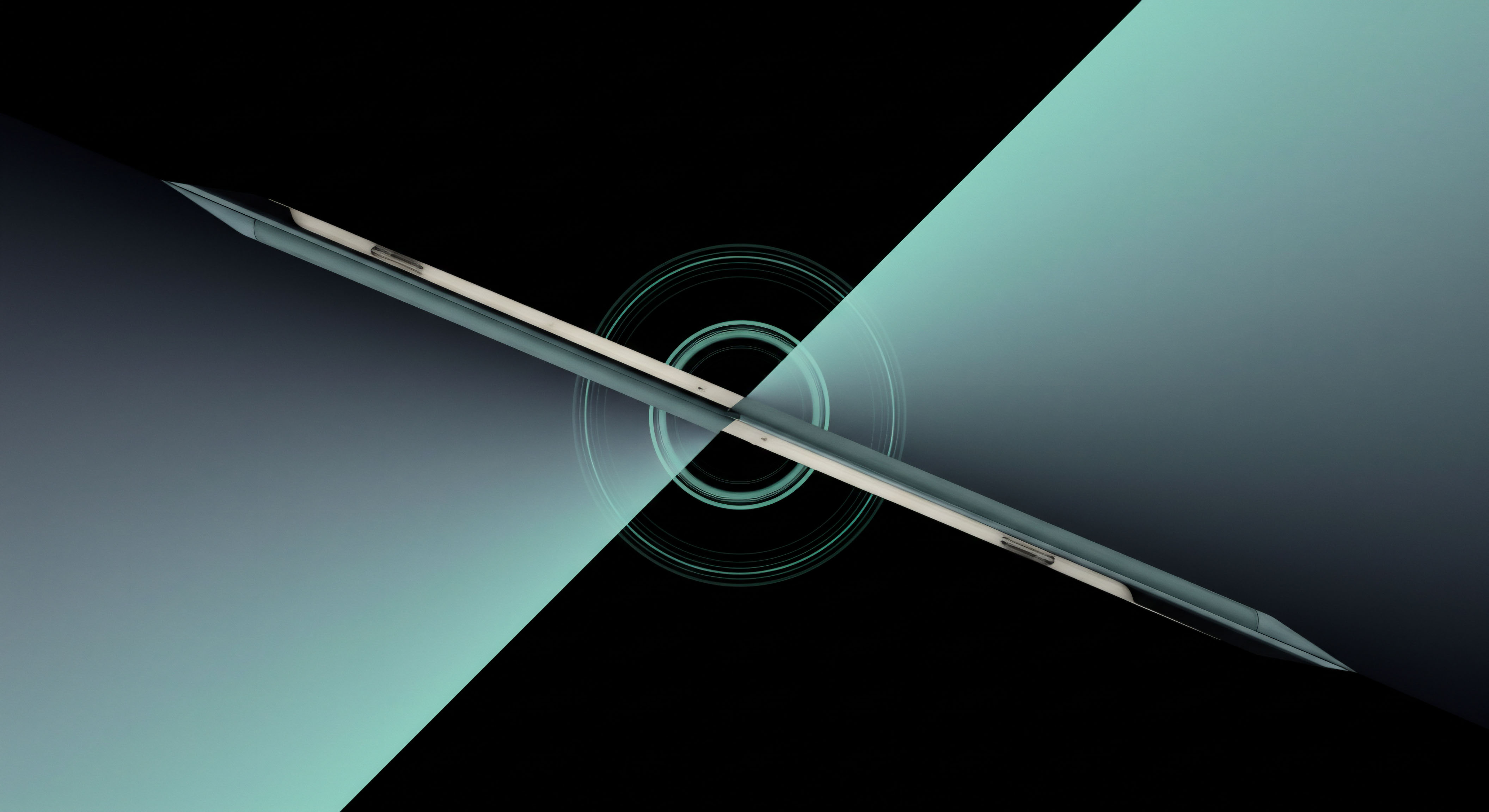

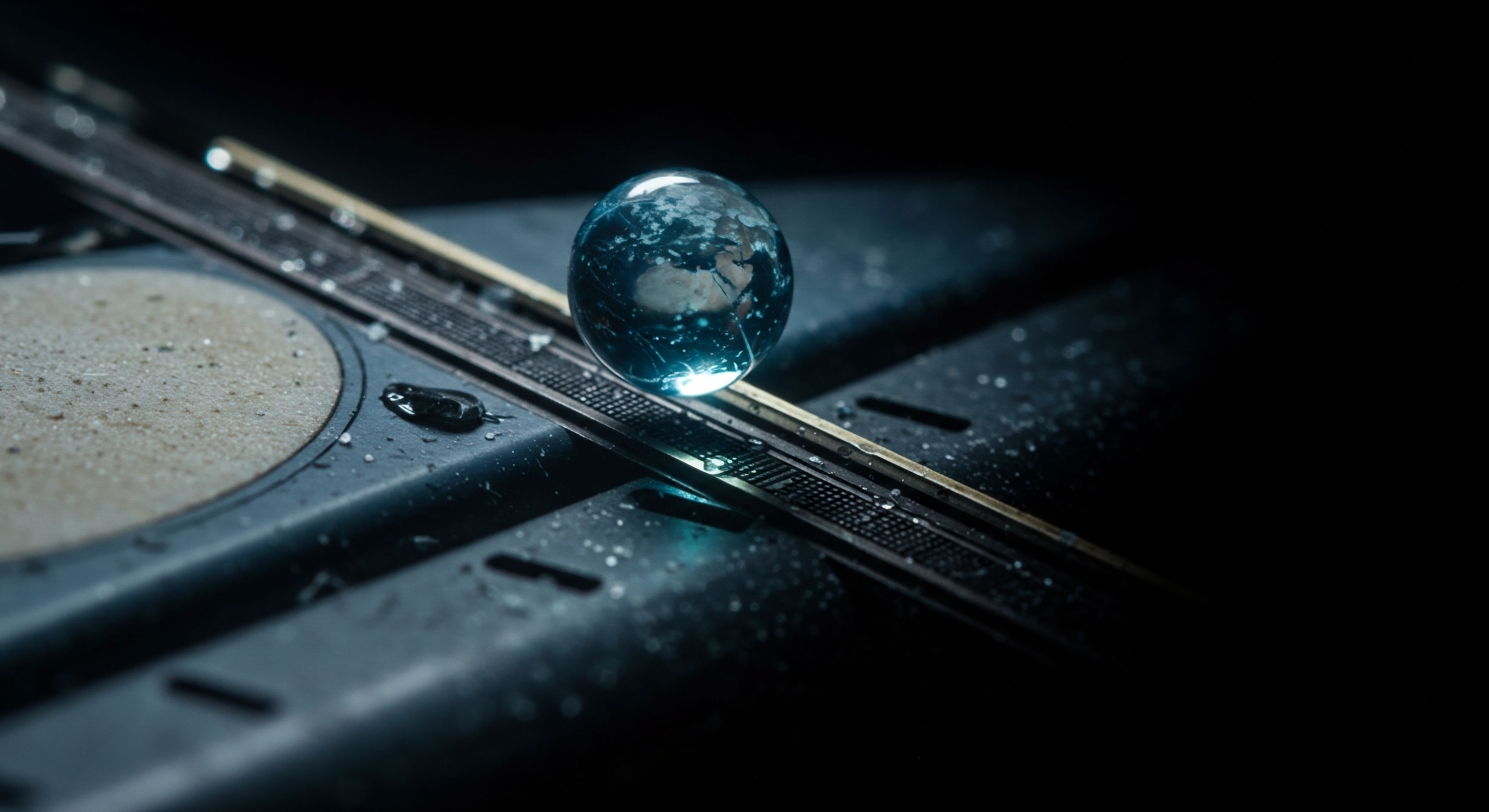

This architectural mismatch creates immediate operational complexities. A digital asset transaction, for instance, can be initiated by a user in one country, validated by a network of miners or validators distributed across dozens of others, and settle in a wallet held by a counterparty in yet another jurisdiction, all within minutes. The question of which regulator has authority becomes profoundly ambiguous. Is it the regulator of the originator, the recipient, the validators, or the location of the exchange where the asset might be traded?

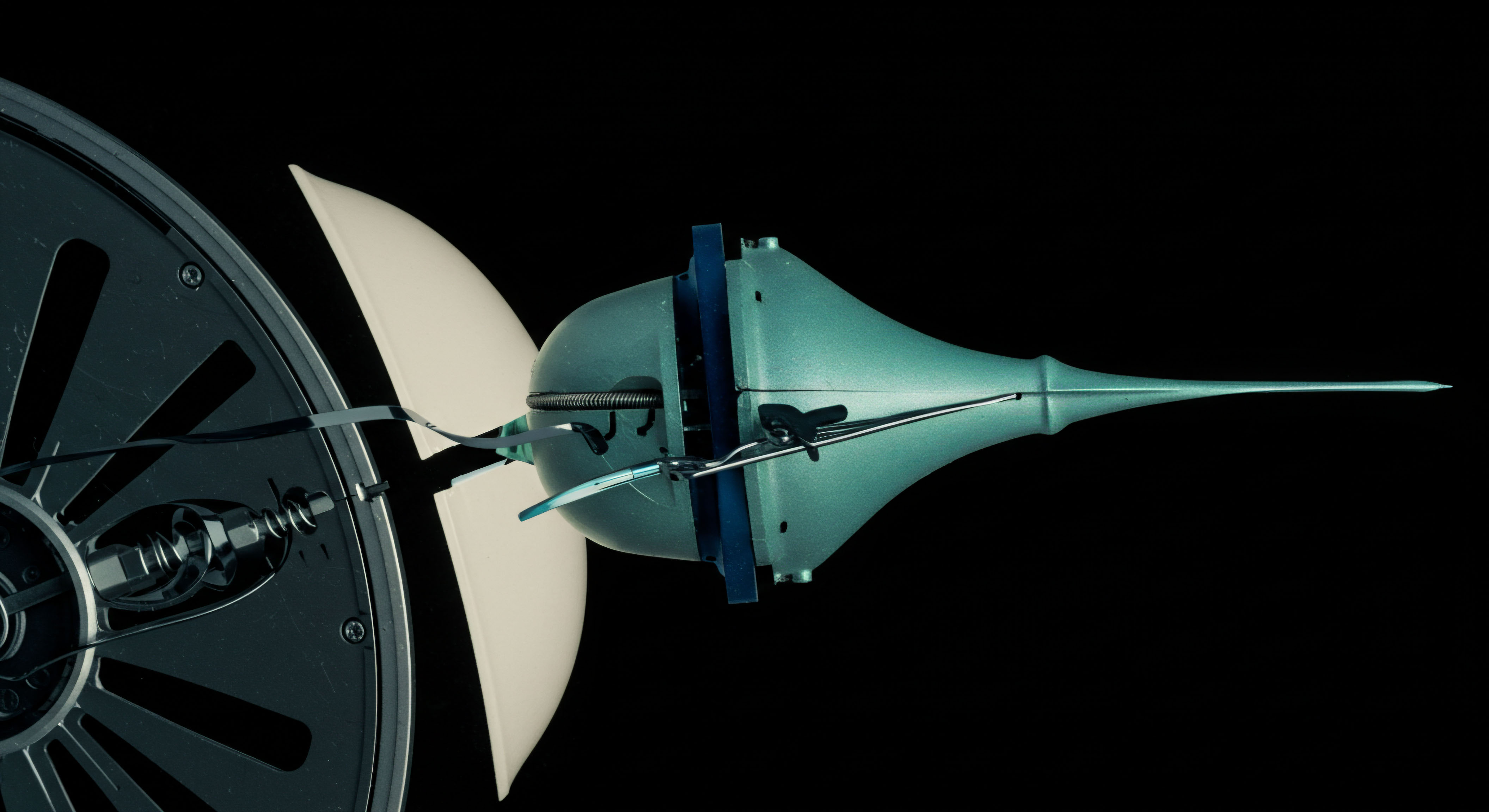

The system’s design resists the very concept of a single point of control that traditional regulation presupposes. This inherent resistance is a primary impediment to harmonization, as any proposed global standard must first define how to map a decentralized reality onto a framework of centralized enforcement points. The challenge is one of translation; converting the logic of a distributed ledger into the language of national statutes is a task for which there is no precedent.

From an institutional perspective, this is not an abstract or academic problem. It manifests as significant operational, legal, and compliance friction. A global financial institution seeking to offer crypto asset services must navigate a labyrinth of conflicting, overlapping, and sometimes contradictory rules. An asset classified as a commodity in one G20 nation may be deemed a security in another, and a form of electronic money in a third.

These classifications trigger entirely different sets of rules regarding issuance, custody, trading, and reporting. The absence of a shared global taxonomy for crypto assets prevents the development of scalable, cross-border operational workflows. Instead, institutions are compelled to build bespoke compliance systems for each market they enter, a process that is both capital-intensive and fraught with legal risk. The dream of a seamless, interconnected digital asset ecosystem, as promised by the technology, is confronted by the reality of a fragmented and disjointed regulatory landscape.

Strategy

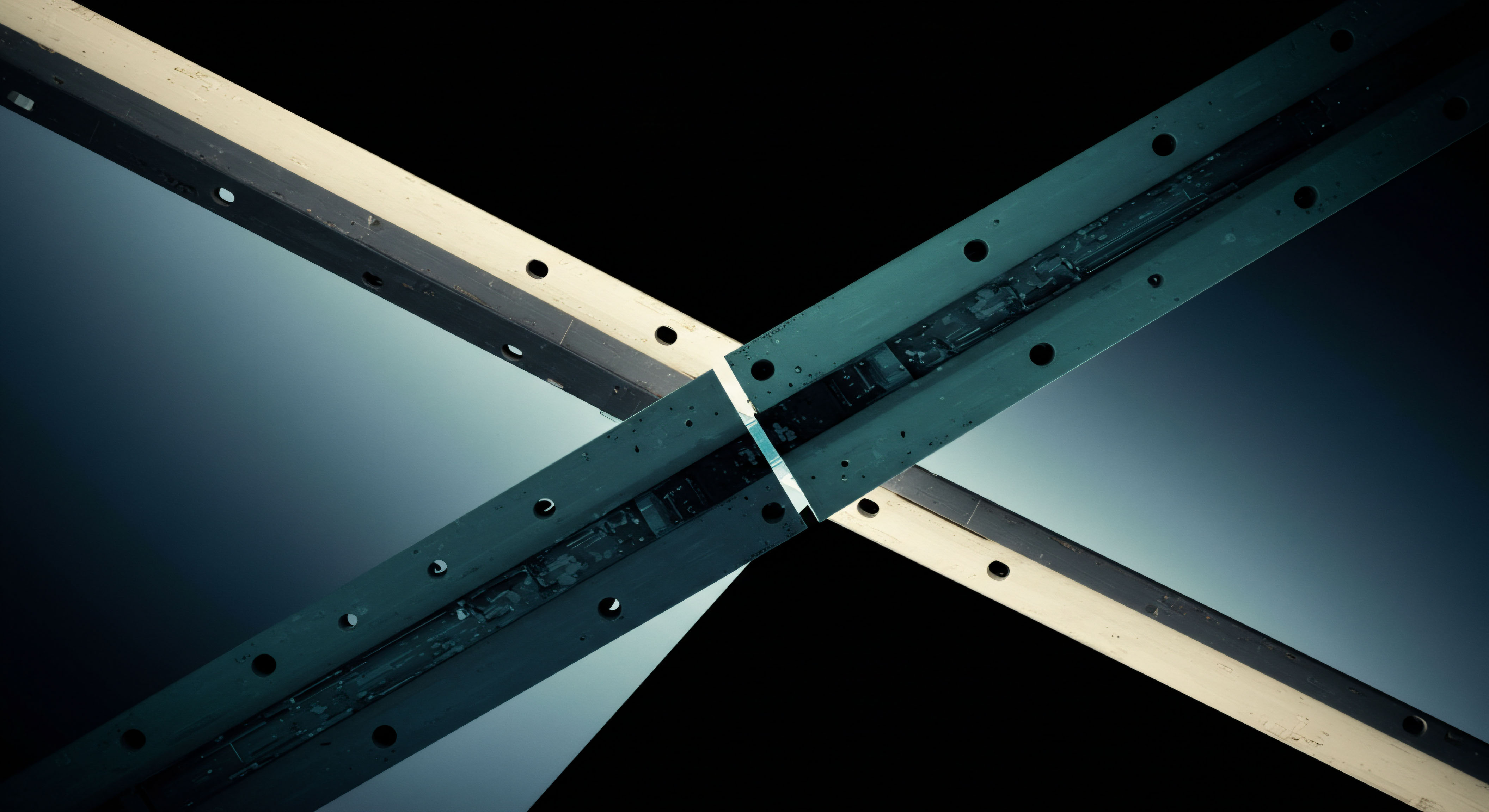

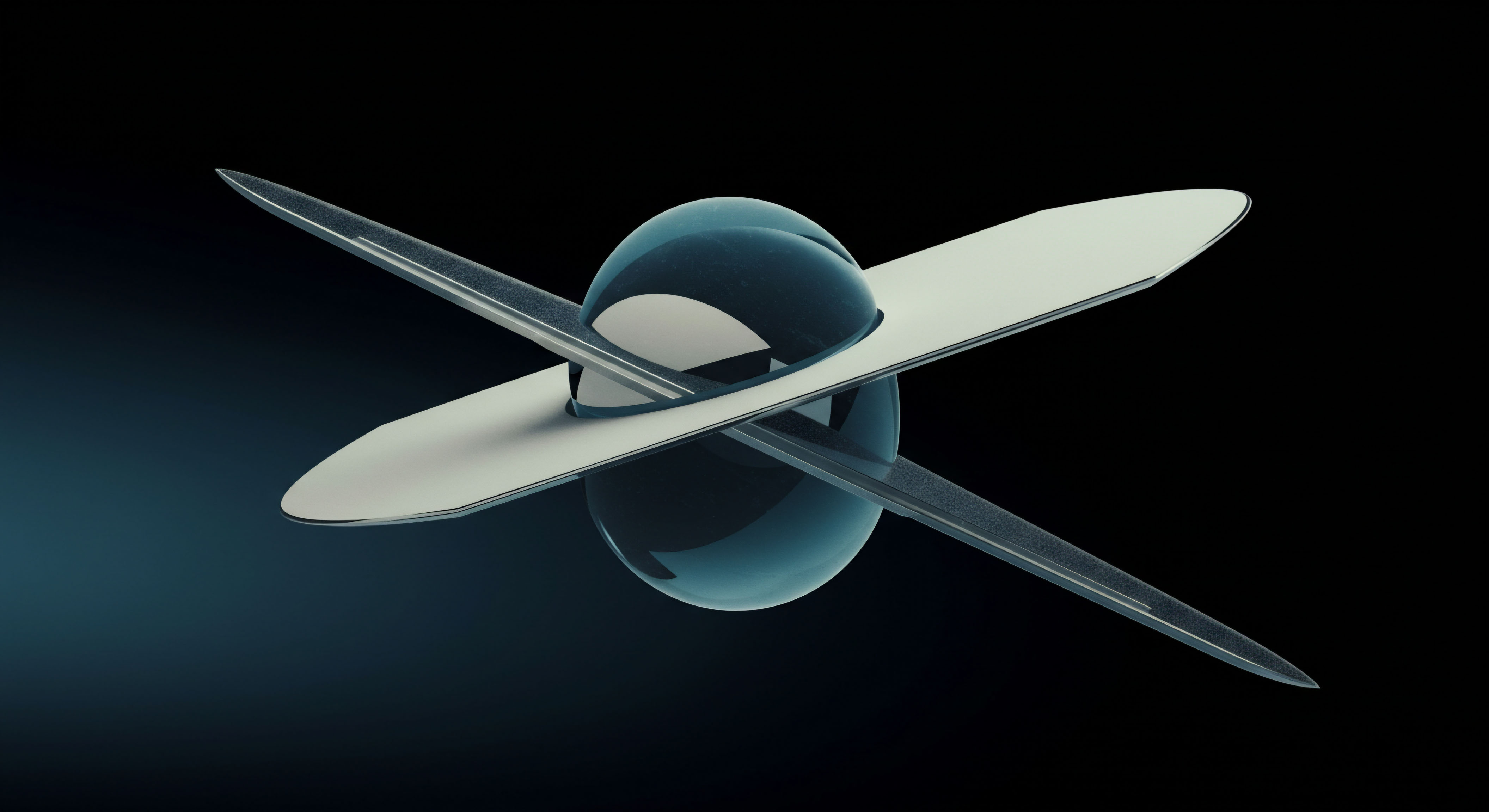

In the absence of a singular, unified global framework, the strategic landscape of crypto asset regulation has evolved into a competitive arena of competing models. Nations and economic blocs are not merely writing rules; they are articulating distinct strategic visions for the future of digital finance. For institutional players, navigating this environment requires moving beyond a simple checklist approach to compliance.

It demands a strategic analysis of these competing regulatory philosophies to understand their long-term implications for market structure, capital allocation, and technological development. Two dominant strategic poles have emerged, each with its own internal logic and operational consequences ▴ the comprehensive, top-down model and the iterative, market-driven approach.

The Comprehensive System Model

The European Union’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation represents the most prominent example of a comprehensive, top-down strategic framework. MiCA’s design philosophy is rooted in the principle of harmonization; it seeks to create a single, detailed rulebook for crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) and issuers operating across all EU member states. This approach provides a high degree of legal certainty and a “regulatory passport,” allowing a firm licensed in one member state to operate throughout the Union. The strategic objective is to foster a unified digital single market, attract investment by providing clear rules of engagement, and protect consumers with a consistent set of standards.

The operational implications of this model are significant. For institutions, MiCA offers a scalable path to market entry. A firm can invest in a single, robust compliance architecture designed to meet MiCA’s stringent requirements, confident that this system will be applicable across a large and wealthy economic bloc. The framework covers a wide spectrum of activities, from the issuance of stablecoins to the operation of exchanges and custody services, leaving little room for regulatory ambiguity.

This clarity reduces legal risk and simplifies strategic planning. However, the model’s comprehensiveness also introduces rigidity. The detailed, prescriptive nature of the rules may be slow to adapt to rapid technological innovation in areas like decentralized finance (DeFi), potentially stifling experimentation. The very process of creating such a detailed framework is lengthy, and by the time it is fully implemented, the technology it seeks to govern may have already evolved.

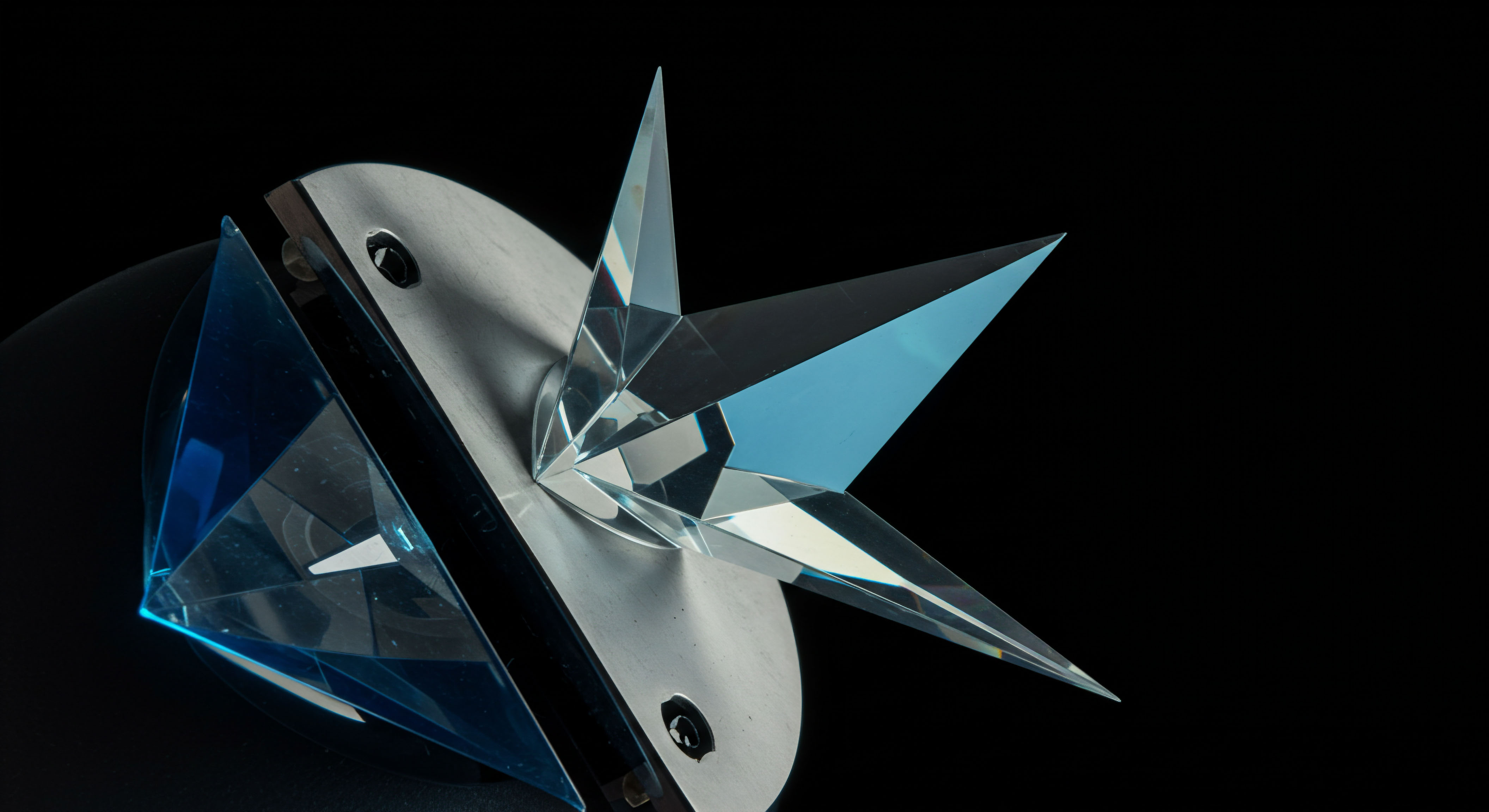

Strategic navigation of crypto regulation involves assessing the trade-offs between comprehensive but rigid frameworks and flexible but fragmented market-driven approaches.

The Iterative Market-Driven Approach

In contrast, the United States has, to date, pursued a more fragmented and iterative strategy. This approach is characterized by the application of existing financial regulations to the crypto asset space, with different agencies asserting jurisdiction based on their interpretation of an asset’s function. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates assets it deems to be securities, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) oversees crypto derivatives, and the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) enforces anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) rules. This strategy is market-driven in the sense that regulatory action often follows market developments and enforcement cases, rather than preceding them with a comprehensive rulebook.

The strategic advantage of this model is its flexibility. It allows regulators to adapt their oversight to new products and services without being locked into a specific legislative framework that may quickly become outdated. It also allows for innovation to occur in the gaps between existing regulations. For institutional participants, however, this approach creates substantial uncertainty.

The lack of a clear, unified federal framework results in a complex compliance calculus, where the legal status of an asset can be ambiguous and subject to change based on future regulatory pronouncements or court rulings. This “regulation by enforcement” can have a chilling effect on development, as firms may be hesitant to invest heavily in products that could later be deemed non-compliant. The operational cost of this uncertainty is high, requiring extensive legal analysis and a reactive compliance posture.

Comparative Strategic Analysis

The choice between these strategic models involves a fundamental trade-off between certainty and flexibility. The following table provides a comparative analysis of these two dominant regulatory strategies:

| Attribute | Comprehensive System Model (e.g. EU’s MiCA) | Iterative Market-Driven Approach (e.g. U.S.) |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Certainty |

High. Provides a clear, detailed rulebook for most crypto-asset activities. |

Low. Relies on interpreting existing laws, leading to ambiguity and “regulation by enforcement.” |

| Operational Scalability |

High. A single compliance framework can be “passported” across a large economic bloc. |

Low. Requires navigating a complex patchwork of federal and state-level regulations. |

| Adaptability to Innovation |

Low to Medium. Prescriptive rules may be slow to adapt to new technologies like DeFi. |

High. Regulators can respond to market changes without needing new legislation. |

| Time to Market |

Slow. The process of drafting and implementing comprehensive legislation is lengthy. |

Fast. Innovation can proceed in areas not explicitly covered by existing rules, albeit with risk. |

| Primary Risk |

Risk of stifling innovation and becoming outdated. |

Risk of legal and regulatory uncertainty, hindering long-term investment. |

International bodies like the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) are working to establish a set of baseline global standards, focusing on the principle of “same activity, same risk, same regulation.” Their strategy is not to create a single global rulebook, but to promote a consistent approach to key risk areas, such as financial stability, investor protection, and market integrity. This approach aims to create a floor for national regulations, reducing the potential for regulatory arbitrage where firms move to jurisdictions with weaker rules. For institutional strategists, monitoring the pronouncements of these bodies is critical, as they signal the likely direction of travel for national regulators and provide a blueprint for a future, more harmonized state.

Execution

The theoretical possibility of a unified global regulatory framework for crypto assets gives way to the immediate operational imperative of executing a compliant global strategy within the current, deeply fragmented reality. For an institutional entity, this is not a waiting game. It is an active process of system design, risk modeling, and technological integration. The objective is to construct a resilient, adaptive operational framework that can function effectively across multiple, often conflicting, regulatory regimes.

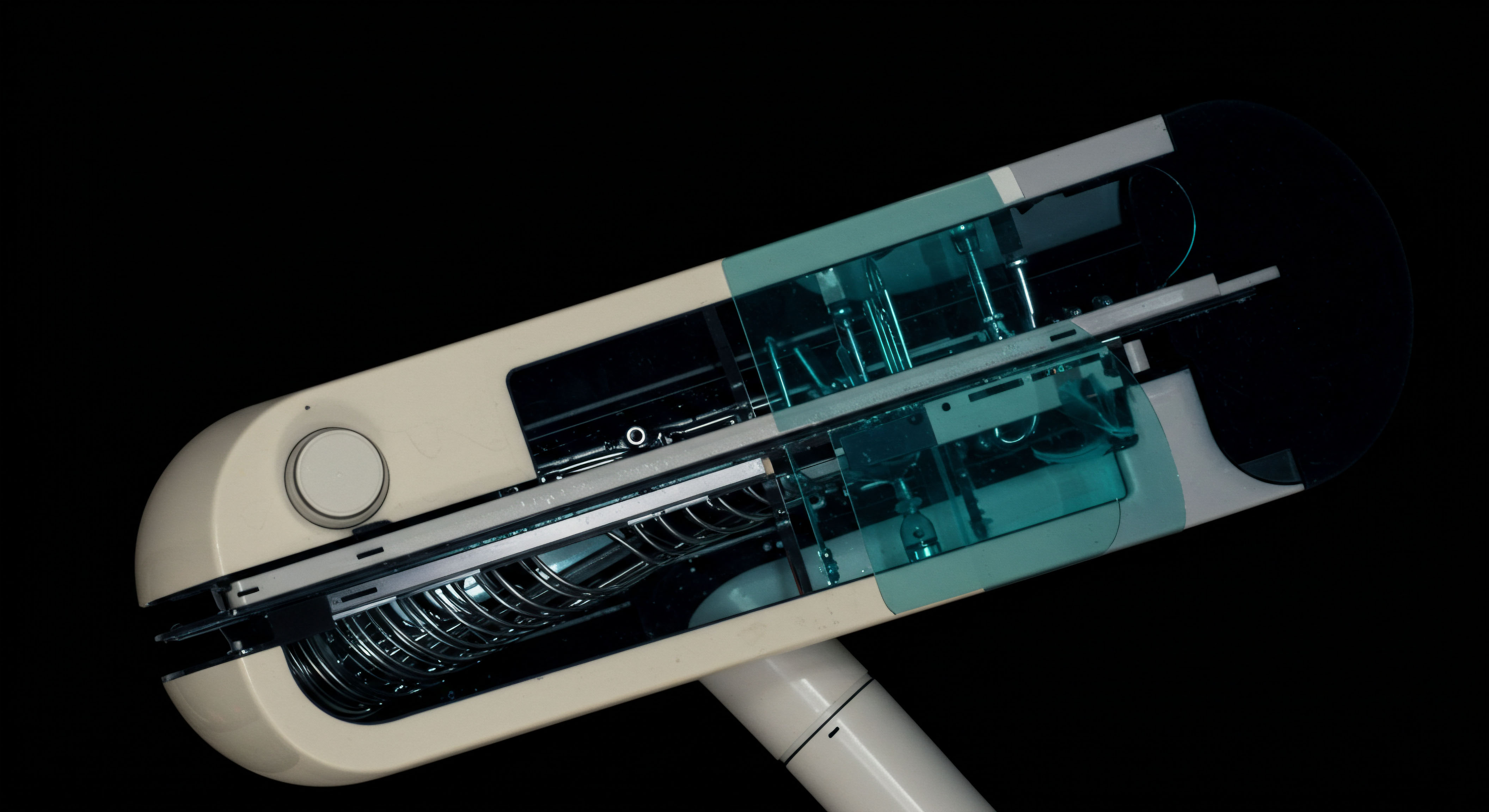

This execution-focused perspective treats regulation not as a static set of constraints, but as a dynamic system of systems that must be navigated with precision. Success is defined by the ability to build a compliance architecture that is both robust enough to satisfy the most stringent regulators and flexible enough to adapt to a constantly shifting global landscape.

The Operational Playbook

An institution seeking to operate globally must develop a clear, systematic playbook for managing cross-jurisdictional regulatory risk. This playbook is a multi-stage process that moves from high-level policy to granular technological implementation.

- Establish a Global Regulatory Intelligence Function. The first step is the creation of a dedicated function responsible for monitoring the regulatory environment in all relevant jurisdictions. This is not a passive activity. It involves active engagement with regulators, participation in industry consultations, and the use of sophisticated legal tech platforms to track legislative and policy changes in real time. The output of this function is a continuously updated “regulatory map” that identifies key requirements, restrictions, and safe harbors in each market.

- Develop a Unified Asset Taxonomy. A core operational challenge is that different jurisdictions classify the same crypto asset in different ways. An institution must create its own internal, global taxonomy that maps each asset to its potential classifications (e.g. security, commodity, utility token, e-money token) under the laws of each target jurisdiction. This internal taxonomy becomes the master data source that drives all subsequent compliance processes.

- Implement a “Highest Common Denominator” Compliance Policy. The firm should establish a baseline global compliance policy based on the strictest applicable regulations. For example, Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures should be designed to meet the standards of the most demanding regulator (often adhering to the FATF Travel Rule recommendations). While this may result in higher initial compliance costs, it minimizes the risk of a catastrophic failure in a key market and provides a solid foundation that can be adjusted with jurisdiction-specific riders.

-

Geofence and Ringfence System Architecture. The technological architecture must be designed to enforce jurisdictional restrictions programmatically. This involves ▴

- Geofencing ▴ Using IP address analysis, GPS data, and other indicators to restrict access to certain products and services based on a user’s physical location.

- Ringfencing ▴ Structuring the legal and operational setup so that activities in one jurisdiction are legally and financially separated from those in others. This can contain the fallout from adverse regulatory action in a single market.

- Conduct Continuous Scenario-Based Stress Testing. The operational framework must be tested against a range of potential regulatory shocks. What happens if a major jurisdiction bans a specific type of stablecoin? What if a key asset is declared a security by the SEC? These scenarios should be modeled to understand their potential impact on liquidity, capital, and operations, allowing the firm to develop contingency plans in advance.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

The cost and complexity of regulatory fragmentation can be quantified. By modeling the operational and capital impacts of different regulatory regimes, an institution can make data-driven decisions about market entry and product development. The table below presents a simplified model of the varying capital requirements for a bank holding a hypothetical crypto asset, illustrating the financial consequences of regulatory divergence.

| Jurisdiction | Regulatory Framework | Asset Classification | Risk-Weighting (Illustrative) | Resulting Capital Charge (on a $10M Exposure) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union |

MiCA & Basel Committee Standards |

Group 2 Cryptoasset (Fails classification conditions) |

1250% (Effectively requires capital to cover the full exposure) |

$10,000,000 |

| Switzerland |

FINMA Guidance |

Payment Token with robust network |

800% (High-risk, but below full deduction) |

$8,000,000 |

| Singapore |

Payment Services Act |

Digital Payment Token |

Varies based on specific risk assessment, potentially lower for established tokens. |

~ $4,000,000 – $6,000,000 |

| United States |

Patchwork (SEC/CFTC/Federal Reserve) |

Ambiguous (Potentially an unregistered security) |

Effectively 1250% due to legal uncertainty and prudential conservatism. |

$10,000,000 |

This quantitative analysis reveals that the decision to operate in a particular jurisdiction is not merely a legal one; it is a profound capital allocation decision. The same asset can have dramatically different impacts on a firm’s balance sheet depending on the prevailing regulatory philosophy. An institution can use this type of modeling to optimize its global footprint, concentrating its activities in jurisdictions that offer a more favorable balance of market opportunity and capital efficiency.

Predictive Scenario Analysis

To bring these challenges to life, consider the hypothetical case of “Aethelred Bank,” a mid-sized European financial institution with ambitions to launch a Euro-denominated stablecoin, “EUR-S,” for use in global trade finance. The bank’s operational team is tasked with charting a course through the fragmented regulatory environment. Their initial plan is to secure a license under MiCA in the EU, which provides a clear path to issuance and passporting within the Union.

The MiCA framework requires them to hold 1:1 reserves in highly liquid assets, establish robust governance procedures, and provide clear redemption rights for holders. The process is arduous but clear.

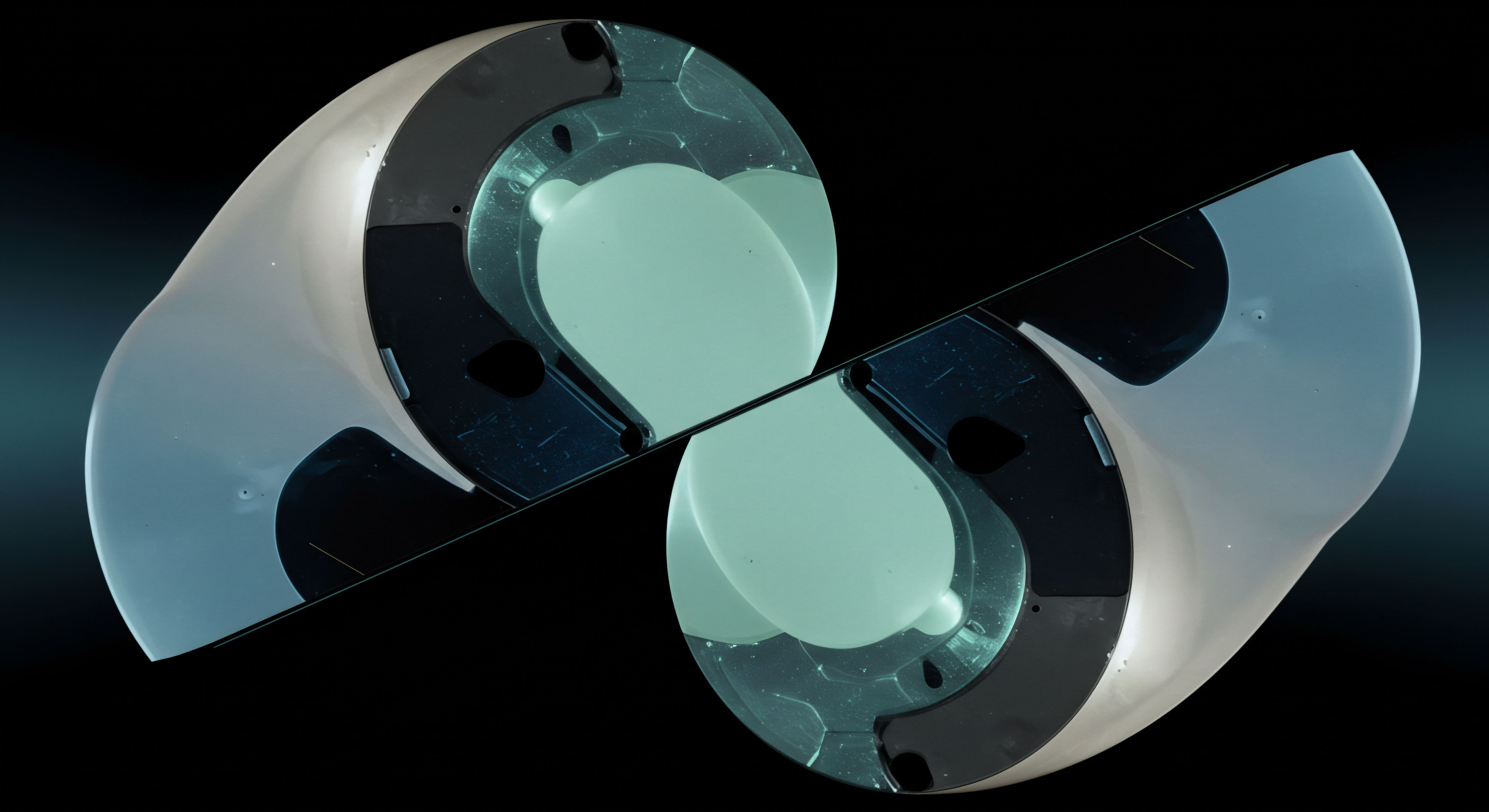

The first major friction point arises when Aethelred seeks to make EUR-S available to corporate clients in the United States. The US has no equivalent to MiCA. The bank’s legal team determines that if EUR-S is used to facilitate transactions that could be interpreted as investments, it might fall under the SEC’s jurisdiction as a security. To mitigate this, they must implement a complex monitoring system to track the usage of each EUR-S token by US clients, a costly and technologically demanding task.

Furthermore, the US Treasury requires them to comply with its stringent AML/CFT reporting standards, which differ in their specifics from the EU’s AMLD5/6 directives. The compliance team must now run two parallel transaction monitoring systems, one for EU rules and one for US rules, and reconcile the outputs.

The situation becomes more complex when a major client in the UK wishes to use EUR-S for supply chain financing. The UK, post-Brexit, is developing its own regulatory regime for stablecoins. While broadly aligned with international principles, it contains unique requirements around the legal status of the coin and the specifics of the reserve assets. Aethelred’s treasury department discovers that certain high-quality liquid assets acceptable under MiCA are not permissible under the UK’s proposed rules.

This forces them to segregate their reserve pools, creating one MiCA-compliant reserve and a separate, smaller UK-compliant reserve. This operational bifurcation increases costs and reduces the efficiency of their treasury management.

Finally, a potential corporate partner in Singapore wants to integrate EUR-S into its payment systems. Singapore’s Payment Services Act provides a clear framework for digital payment tokens, but it imposes its own set of technology risk management standards and requires specific reporting to the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). Aethelred’s technology team must now build a third set of APIs and reporting modules specifically for the MAS. Within a year of launch, the seemingly straightforward project of issuing a Euro-backed stablecoin has morphed into a multi-headed operational hydra.

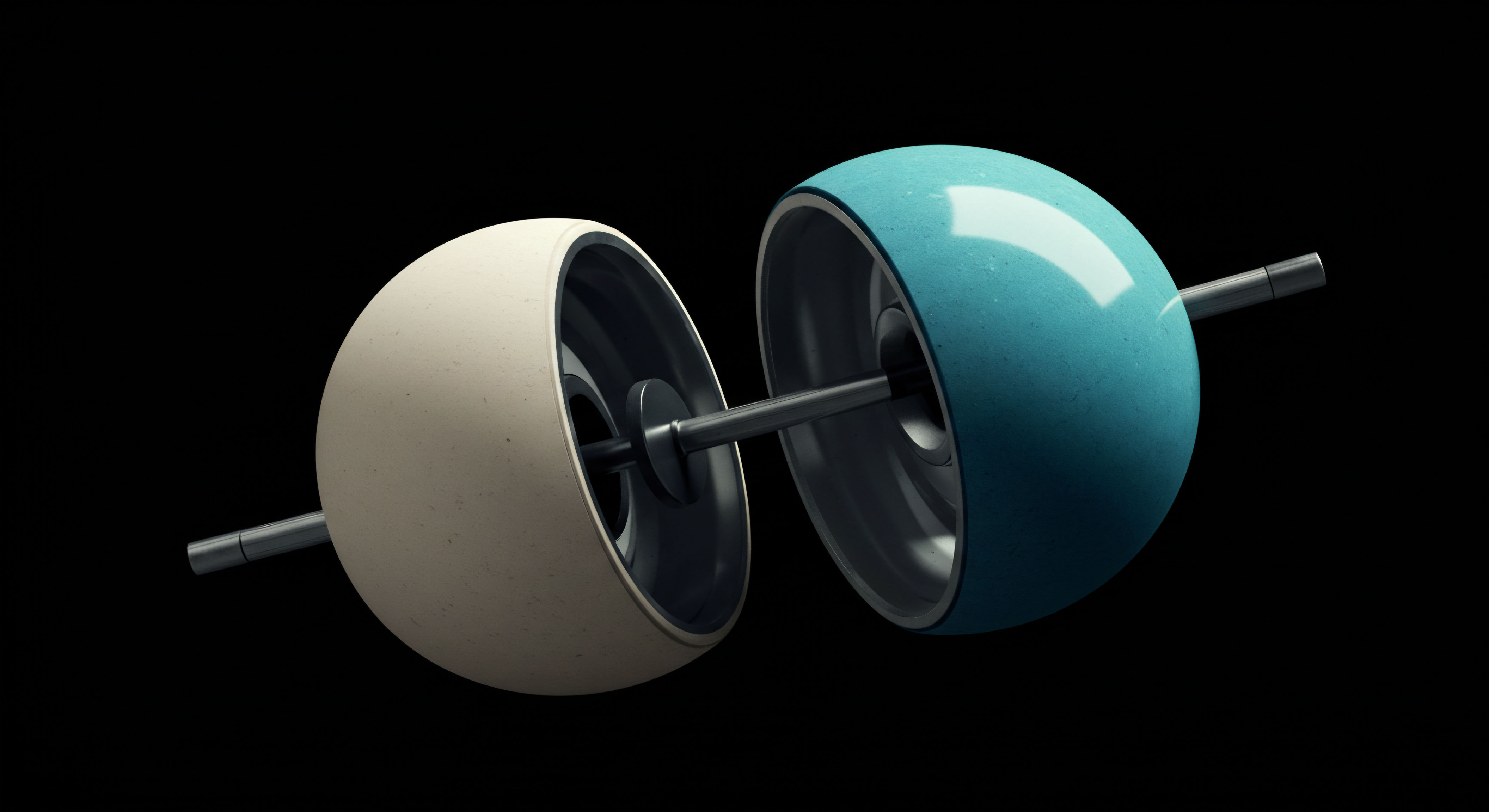

The bank is running four different compliance and reporting frameworks for what is, technologically, a single, fungible asset. The dream of a frictionless global payment instrument has been shattered by the reality of regulatory fragmentation. This case study illustrates that achieving global scale in the current environment is an exercise in managing complexity, not eliminating it.

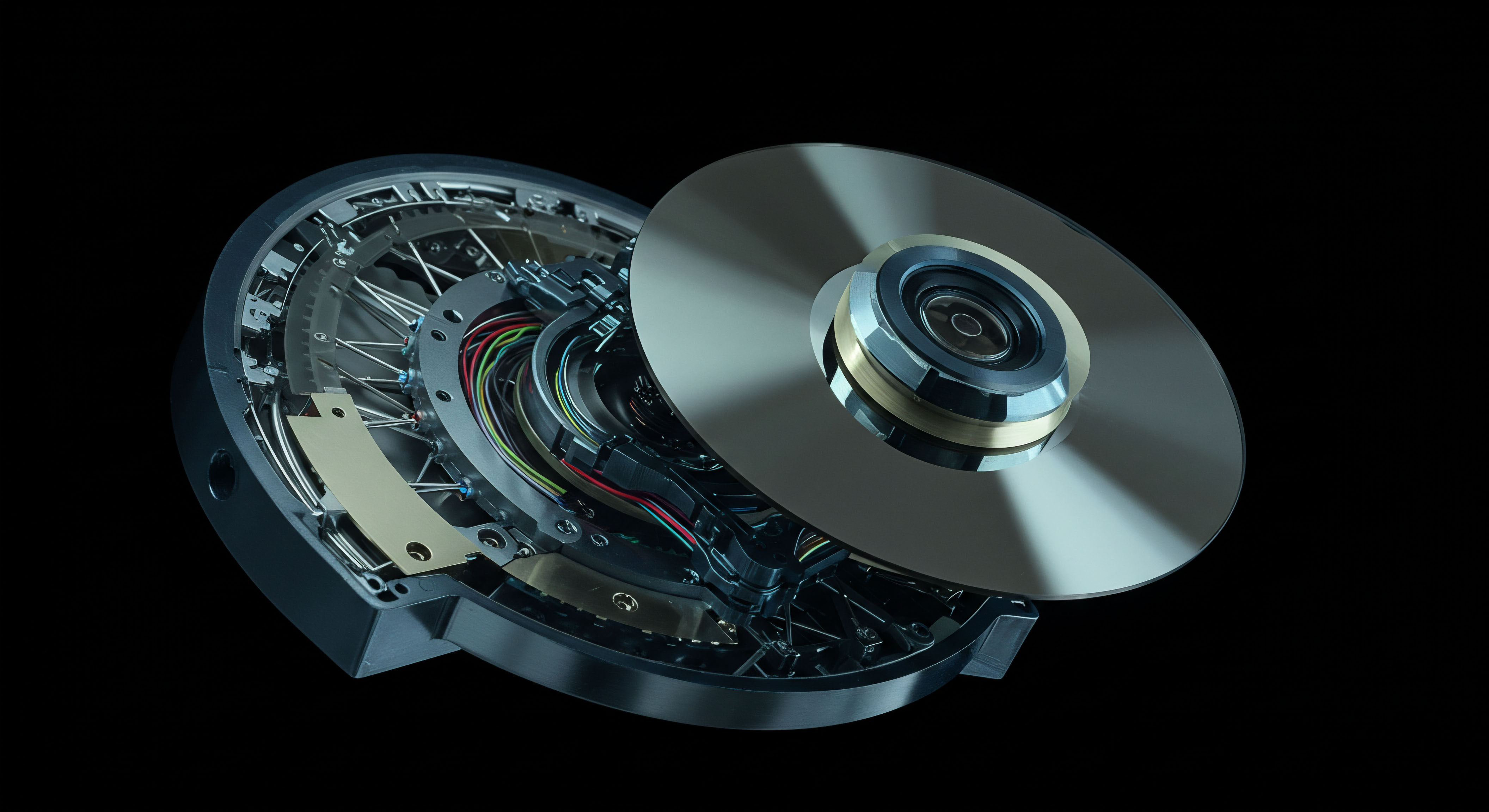

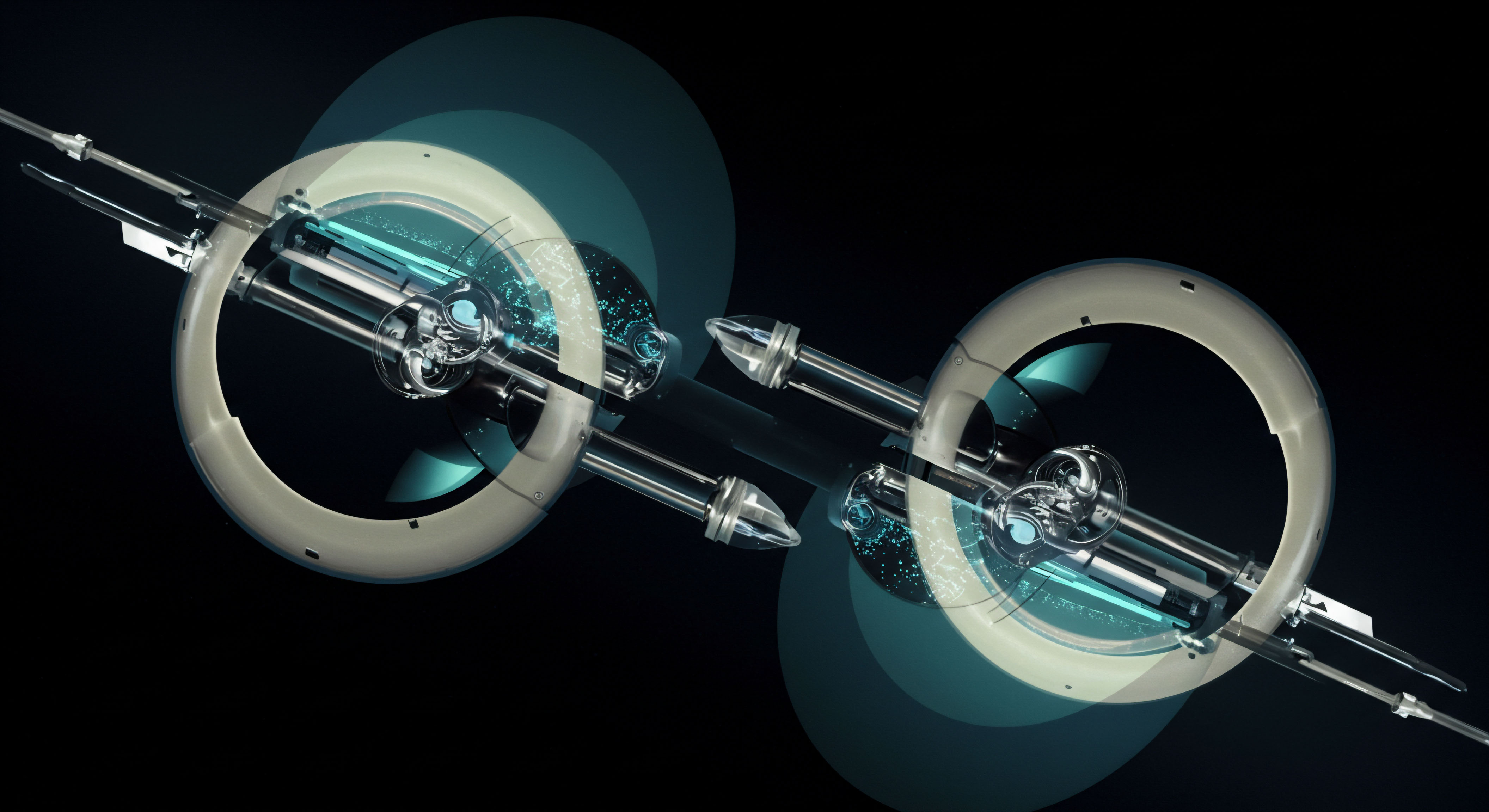

System Integration and Technological Architecture

The execution of a global crypto strategy is ultimately a technological challenge. An institution’s ability to navigate regulatory fragmentation depends on the sophistication of its “RegTech” (Regulatory Technology) stack. This is not a single piece of software, but an integrated architecture of systems designed to automate and manage compliance obligations across jurisdictions.

- Core Component ▴ The Compliance Engine. At the heart of the architecture is a rules-based compliance engine. This engine ingests the firm’s global regulatory map and its internal asset taxonomy. For every transaction, the engine applies the relevant set of jurisdictional rules. For example, a transaction involving a user in France and an asset classified as a “digital asset security” would trigger a specific set of rules related to investor disclosures and reporting, while a transaction involving a user in Japan and a “payment token” would trigger a different set of AML checks.

-

API Layer for Data Ingestion. The compliance engine must be fed with real-time data from multiple sources via a robust set of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). This includes ▴

- On-chain data ▴ From blockchain analytics providers like Chainalysis or Elliptic to trace the origin of funds and identify high-risk wallets.

- Off-chain data ▴ From KYC/AML service providers to verify customer identities.

- Market data ▴ From exchanges and data vendors to price assets for capital and risk calculations.

- Modular Reporting System. The architecture must include a modular reporting system that can generate regulatory reports in the specific formats required by different authorities. This system should be designed so that new modules can be added quickly as the firm enters new markets or as reporting requirements change. For example, it should be able to generate a suspicious activity report (SAR) for FinCEN, a threshold transaction report for AUSTRAC in Australia, and a report for the FATF Travel Rule data exchange.

Ultimately, the absence of a unified global regulatory framework forces institutions to internalize the function of harmonization. They must build their own private, internal “global framework” through a combination of policy, quantitative modeling, and sophisticated technological architecture. This is a formidable undertaking, but it is the only viable path to executing a compliant and successful global strategy in the world of digital assets.

References

- Financial Stability Board. (2023). Global Regulatory Framework for Crypto-asset Activities.

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). Financial Stability Report.

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2022). Prudential treatment of cryptoasset exposures.

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 on markets in crypto-assets (MiCA).

- Arslanian, H. & Fischer, F. (2019). The Future of Finance ▴ The Impact of FinTech, AI, and Crypto on Financial Services. Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Hara, M. (2017). High-Frequency Trading ▴ A Practical Guide to Algorithmic Strategies and Trading Systems. Wiley.

- Lo, A. W. (2017). Adaptive Markets ▴ Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought. Princeton University Press.

- Financial Action Task Force. (2023). Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers.

- International Organization of Securities Commissions. (2023). Policy Recommendations for Crypto and Digital Asset Markets.

- UK Treasury. (2023). Future financial services regulatory regime for cryptoassets ▴ Consultation and call for evidence.

Reflection

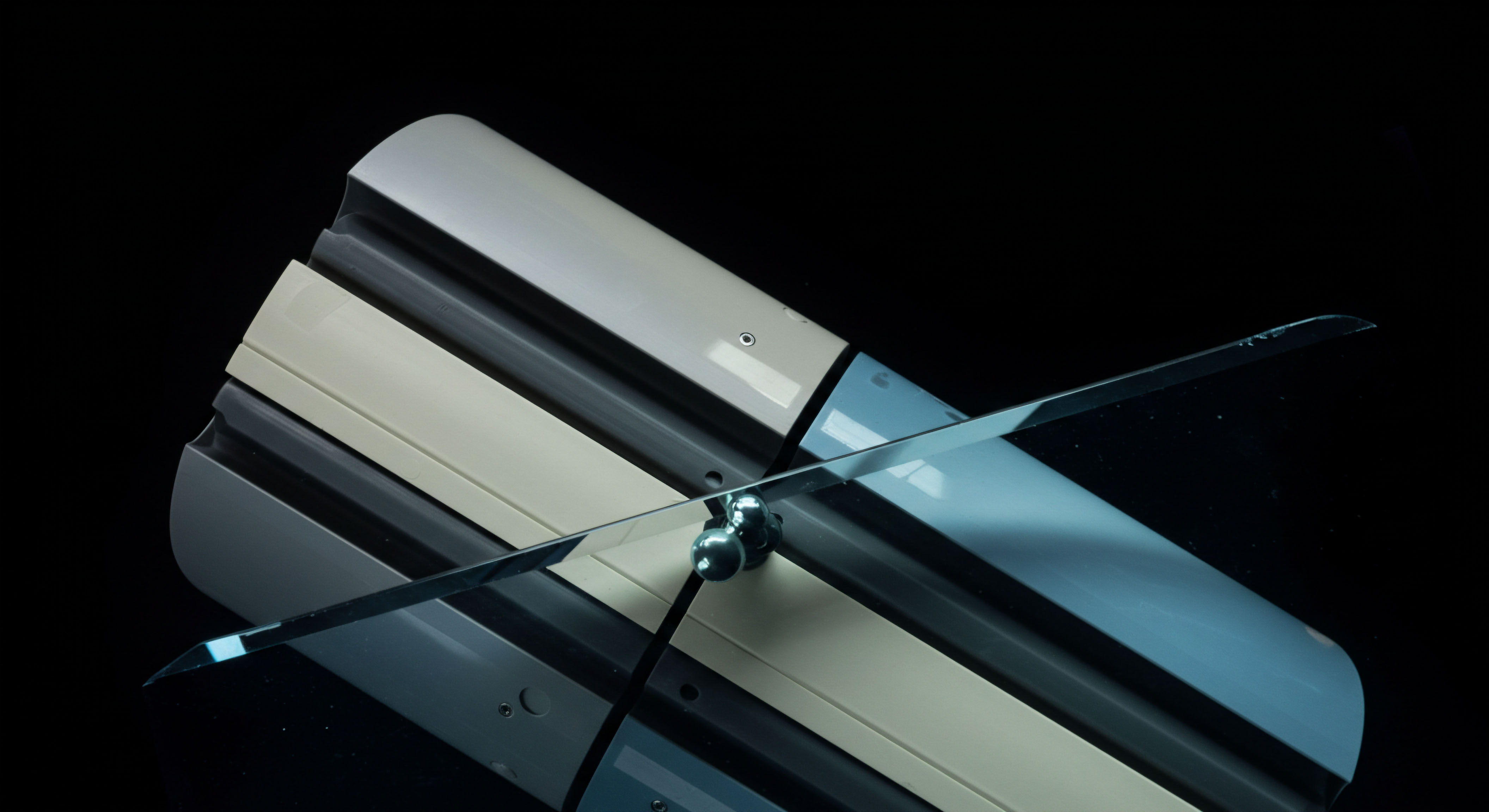

The journey through the fragmented labyrinth of global crypto asset regulation ultimately leads back to a foundational question for any institutional participant ▴ what is the architecture of our own operational intelligence? The pursuit of a unified external framework, while a laudable long-term goal for the international community, can obscure the immediate and actionable task of building a superior internal one. The knowledge gained about the competing models of regulation, the quantitative impacts of jurisdictional divergence, and the technological requirements for compliant execution are not merely academic points of interest. They are the essential components of a dynamic, resilient operational system.

Viewing the global regulatory landscape as a complex, adaptive system, rather than a static set of rules to be obeyed, shifts the institutional posture from reactive compliance to proactive design. The challenge is to construct an internal framework that mirrors the environment it seeks to navigate ▴ one that is modular, adaptable, and capable of processing disparate inputs to produce a coherent, risk-managed output. The true strategic advantage lies not in waiting for the world’s regulators to agree, but in building an operational capacity that thrives on their disagreement. This is the ultimate execution test ▴ to create a system of internal certainty in a world of external ambiguity, thereby transforming a global regulatory challenge into a unique institutional capability.

Glossary

Unified Global Regulatory Framework

Digital Asset

Crypto Asset

Crypto Asset Regulation

Mica

Compliance Architecture

Financial Stability Board

Regulatory Arbitrage

Global Regulatory Framework

Global Regulatory

Fatf Travel Rule

Regtech