Concept

The core tension within a Central Counterparty (CCP) originates from its dual mandate. It operates as a private, profit-seeking entity while simultaneously serving a critical public function as a guarantor of financial stability. This structure inherently creates a potential for conflict. The introduction of a CCP’s own capital into the default waterfall, a mechanism known as “skin in the game” (SITG), is designed as an alignment tool.

It forces the CCP to internalize a portion of the risk it guarantees, creating a direct financial incentive to manage that risk with precision. The fundamental question is whether this alignment mechanism is potent enough to supersede the powerful, ever-present objective of profit maximization.

A CCP generates revenue through clearing fees, investment returns on collateral, and other service charges. To maximize these revenues, a CCP might be incentivized to expand its services, clear a wider array of more complex or volatile products, or relax its membership criteria to attract more participants. Each of these actions, while commercially logical, can systematically increase the risk profile of the clearinghouse. A larger, more diverse membership introduces a wider range of credit risks.

Clearing novel, less-liquid derivatives can complicate default management procedures and increase potential losses. Optimizing investment returns on trillions of dollars of posted collateral introduces investment risk. These profit-driven behaviors stand in direct opposition to the CCP’s role as a bulwark against systemic contagion.

A CCP’s skin in the game is the portion of its own capital at risk in a default, intended to align its risk management with member interests.

The placement and size of SITG within the default waterfall are the critical parameters that define its effectiveness. The default waterfall is the sequential application of financial resources to cover the losses from a defaulting clearing member. Typically, the defaulter’s own initial margin and default fund contribution are used first. The CCP’s SITG is often the next tranche of capital to be consumed.

Only after the CCP’s capital is exhausted are the mutualized default fund contributions of the surviving members utilized. This positioning makes the CCP’s capital the first line of defense for the collective membership, theoretically ensuring its interests are aligned with those of its non-defaulting participants. However, if the amount of SITG is trivial compared to the overall size of the default fund and the potential profits from riskier activities, its influence as an incentive mechanism diminishes significantly.

This dynamic creates a complex agency problem. The CCP’s management and shareholders are the agents, while the clearing members and the broader financial system are the principals who rely on the CCP’s prudent risk management. Without adequate SITG, the CCP may be incentivized to privatize gains (through higher fees on riskier products) while socializing losses (which are borne by the surviving members’ default fund contributions). A robust SITG tranche forces the CCP to absorb a meaningful portion of the initial losses, directly impacting its equity and profitability.

This creates a powerful incentive for the CCP’s board and senior management to enforce rigorous risk management, from setting conservative initial margin levels to conducting stringent due diligence on new members and products. The conflict, therefore, is a continuous negotiation between the commercial pressures to grow and the prudential necessity to remain resilient, with the magnitude of SITG serving as the primary fulcrum balancing these opposing forces.

Strategy

Analyzing the conflict of interest within a CCP requires a strategic framework that dissects the incentives of all parties involved ▴ the CCP’s management and shareholders, its clearing members, and the regulatory bodies overseeing the system. The central strategic tension is the trade-off between risk and revenue, a dynamic that is managed through the architectural design of the CCP’s risk management systems, most notably the default waterfall. The strategy for mitigating this conflict revolves around calibrating the CCP’s “skin in the game” to a level that makes prudent risk management the most profitable long-term strategy for the CCP itself.

The Duality of CCP Objectives

A CCP’s strategic objectives can be viewed through two distinct lenses. As a commercial enterprise, its goal is to maximize shareholder value. As a systemic risk manager, its goal is to ensure the stability of the markets it clears. These objectives are not always in opposition, but they create friction at critical decision points.

- Profit-Maximization Objective This objective is pursued by increasing clearing volumes, expanding into new product classes, and optimizing returns on invested collateral. The strategic imperative is growth. A CCP might lower its fees to attract business from a competitor, approve a new, volatile cryptocurrency derivative for clearing, or alter its collateral investment policy to seek higher yields. Each action is designed to enhance revenue.

- Risk-Mitigation Objective This objective is mandated by regulators and demanded by clearing members who rely on the CCP to protect them from counterparty default. The strategic imperative is resilience. This involves setting conservative margin requirements, enforcing strict membership standards, and maintaining a robust default waterfall. These actions increase safety but can also increase the cost of clearing, potentially driving away business and reducing profitability.

How Does Skin in the Game Modulate CCP Behavior?

Skin in the game acts as the primary strategic lever to align these divergent objectives. Its effectiveness is a function of its size and position within the default waterfall. A larger SITG tranche makes the CCP more sensitive to default losses, thus shifting its strategic calculus towards more conservative risk management. It transforms an abstract risk into a tangible threat to the CCP’s own equity.

Consider the strategic decision of whether to clear a new, high-risk derivative product. Without significant SITG, the CCP’s analysis might be skewed towards the potential fee income. The risk is largely externalized to the clearing members, whose default fund contributions would absorb the majority of losses. With a substantial SITG tranche, the CCP is forced to weigh the potential fee income against a credible threat to its own capital.

This internalizes the risk and incentivizes a more thorough and cautious evaluation of the new product. The table below illustrates how varying levels of SITG can influence a CCP’s strategic orientation.

| Strategic Decision Point | Low SITG Environment (Profit-Focused) | High SITG Environment (Risk-Aware) |

|---|---|---|

| New Product Approval | Incentive to approve higher-risk, higher-fee products, as potential losses are primarily mutualized among members. | Incentive to apply stringent risk analysis, as a default could significantly erode the CCP’s own capital. |

| Initial Margin Modeling | Pressure to set lower margins to attract more clearing business and reduce costs for members, increasing the CCP’s competitiveness. | Incentive to set conservative margins to create a larger buffer, protecting the CCP’s SITG tranche from being breached. |

| Membership Expansion | Motivation to lower entry barriers to increase the number of fee-paying members, potentially accepting firms with weaker credit profiles. | Strong incentive to enforce rigorous credit standards for all members to minimize the probability of a default that could trigger SITG losses. |

| Collateral Investment Policy | Temptation to invest cash collateral in slightly riskier assets to generate higher returns, boosting CCP profitability. | Focus on capital preservation, investing collateral in highly liquid, low-risk assets to ensure its availability during a crisis. |

Regulatory Frameworks as a Strategic Constraint

Global regulatory standards, such as the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) developed by CPMI-IOSCO, provide a foundational strategic constraint on CCPs. These principles mandate robust governance, comprehensive risk management frameworks, and sufficient financial resources. Principle 4, for instance, requires a CCP to effectively measure, monitor, and manage its credit exposures to its participants. Principle 15 requires it to identify and manage operational risks.

These regulations create a baseline for prudent behavior. However, many of these principles are qualitative. The quantitative implementation, such as the precise level of SITG, is often left to the discretion of the CCP and national regulators. This is where the conflict of interest can re-emerge, as a CCP may lobby for the minimum possible SITG requirement to preserve its strategic flexibility and maximize its profit potential. The ultimate strategy for ensuring financial stability, therefore, is a combination of robust, principle-based regulation and a sufficiently large, risk-sensitive SITG that makes the cost of imprudent behavior prohibitively high for the CCP itself.

Execution

The execution of a CCP’s dual objectives manifests in its operational risk management protocols and financial architecture. The conflict between safety and profit is not an abstract concept; it is embedded in the day-to-day calculations, policy decisions, and governance structures of the clearinghouse. Examining the precise mechanics of the default waterfall provides the clearest view of how “skin in the game” functions as an executed control mechanism.

The Default Waterfall an Operational Blueprint

The default waterfall is a pre-defined, sequential process for allocating losses in the event a clearing member fails to meet its obligations. It is the operational playbook for a crisis. The structure of this waterfall is the most critical element in determining the incentives of the CCP and its members.

While specific waterfalls vary, a common structure is outlined by regulatory bodies and industry practice. The execution of loss allocation follows a strict hierarchy, moving from resources provided by the defaulter to resources provided by the CCP, and finally to resources provided by the surviving members.

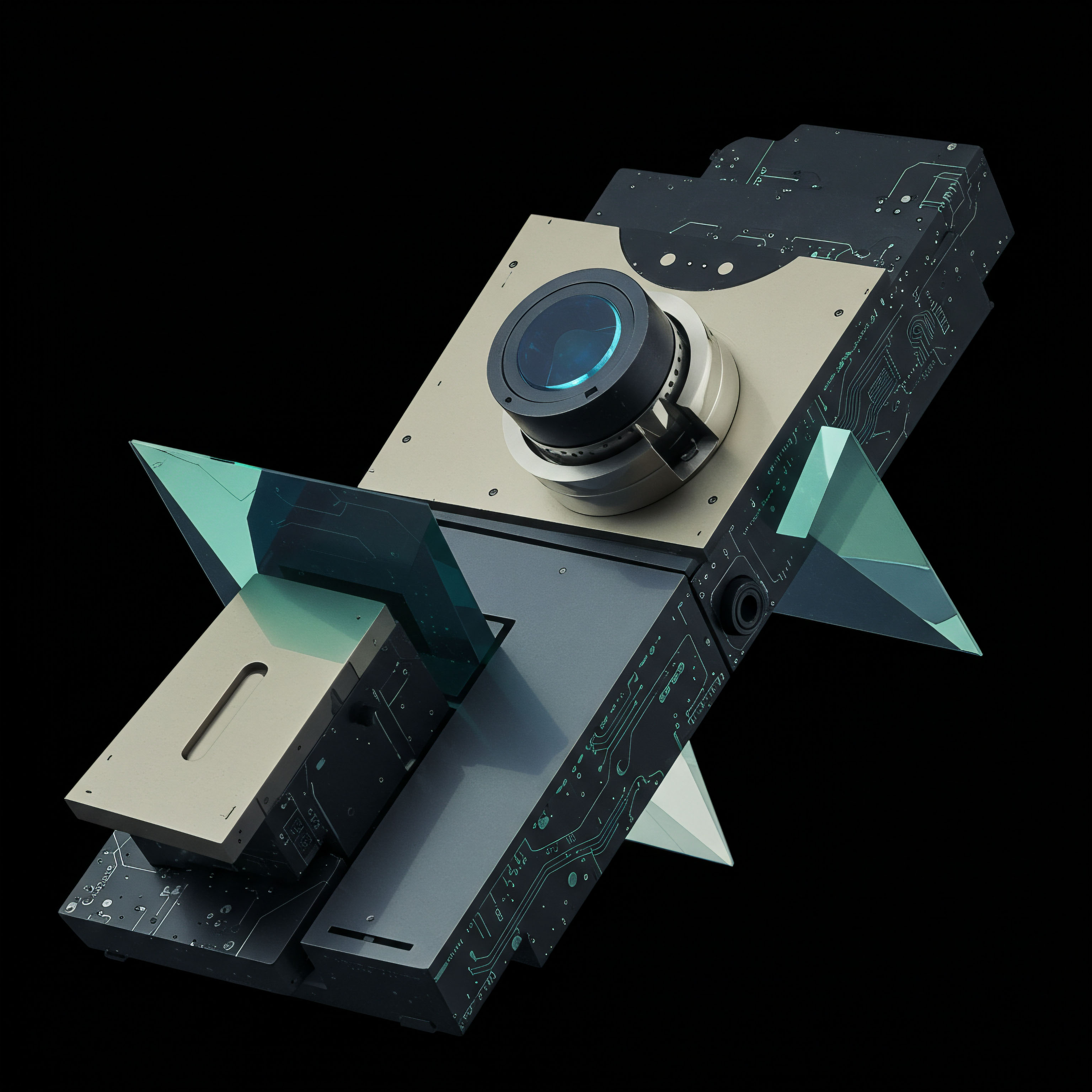

The default waterfall’s structure dictates the sequence of loss allocation, moving from the defaulter’s assets to the CCP’s capital and then to the members’ mutualized funds.

This sequence is paramount. By placing the CCP’s own capital (SITG) after the defaulter’s resources but before the non-defaulting members’ contributions, the waterfall operationally aligns the CCP’s financial health with that of its solvent members. The table below provides a granular, hypothetical example of a default waterfall for a CCP, illustrating the sequential execution of loss absorption.

| Waterfall Tranche | Description | Hypothetical Amount (USD) | Cumulative Coverage (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Defaulter’s Initial Margin | Collateral posted by the defaulting member to cover its potential future exposure. | $500 Million | $500 Million |

| 2. Defaulter’s Default Fund Contribution | The defaulting member’s contribution to the mutualized default fund. | $150 Million | $650 Million |

| 3. CCP’s Skin in the Game (SITG) | The CCP’s own capital contribution, at risk before member funds. | $250 Million | $900 Million |

| 4. Surviving Members’ Default Fund Contributions | The mutualized fund contributed by all non-defaulting members. | $2.5 Billion | $3.4 Billion |

| 5. Member Assessments (Cash Calls) | Additional calls for funds from surviving members, up to a pre-agreed cap. | $2.5 Billion | $5.9 Billion |

What Are the Practical Implications of This Execution?

In a default scenario where total losses amount to $1 billion, the execution would proceed as follows. The first $650 million would be covered by the defaulter’s own resources (Tranches 1 and 2). The next $250 million in losses would be absorbed entirely by the CCP’s SITG (Tranche 3), directly hitting the CCP’s balance sheet and profitability. The remaining $100 million of the loss would then be covered by the surviving members’ default fund contributions (Tranche 4).

In this scenario, the SITG was substantial enough to absorb a significant portion of the loss, but not all of it. This demonstrates the alignment ▴ the CCP suffers a major financial loss, reinforcing the need for prudent risk management. It also shows the limits ▴ if the SITG is exhausted, the risk is ultimately mutualized.

The conflict of interest in execution arises when the CCP has discretion over the parameters that feed into this waterfall. For example:

- Margin Model Calibration A CCP that prioritizes profit might calibrate its margin models to require less initial margin from members, making clearing through it cheaper and more attractive. This, however, reduces the size of Tranche 1, increasing the probability that a default will burn through to the CCP’s SITG and potentially to the members’ mutualized funds.

- Default Fund Sizing The CCP’s methodology for sizing the default fund (Tranches 2 and 4) is another critical execution point. A profit-driven CCP might advocate for a smaller default fund to reduce the financial burden on its members, thereby attracting more business. This again increases the risk to the entire structure.

- Governance and Risk Committees The decisions made in a CCP’s risk committee meetings are where the conflict is most acute. When presented with a proposal to clear a new, complex product, the committee must execute a balancing act. The commercial team will present revenue projections, while the risk management team will present potential loss scenarios. The presence of a significant SITG on the CCP’s balance sheet gives the chief risk officer a powerful, quantitative argument for caution, grounding the discussion in the tangible risk to the firm’s own capital.

Ultimately, the execution of risk management within a CCP is a function of its governance, its operational procedures, and the financial incentives created by its default waterfall. An appropriately sized and positioned SITG is a critical component of this execution, as it ensures that the pursuit of profit is always tempered by the direct, measurable, and painful financial consequences of a risk management failure.

References

- Cont, Rama. “Skin in the game ▴ risk analysis of central counterparties.” 2015.

- McPartland, John, and Rebecca Lewis. “The Goldilocks problem ▴ How to get incentives and default waterfalls ‘just right’.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Economic Perspectives, 2017.

- Ghamami, Samim. “Skin in the Game ▴ Risk Analysis of Central Counterparties.” 2023.

- World Federation of Exchanges. “A CCP’s skin-in-the-game ▴ Is there a trade-off?” 2020.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. “Skin in the Game ▴ Central Counterparty Risk Controls and Incentives.” 2015.

- Global Risk Institute. “Incentives Behind Clearinghouse Default Waterfalls.” 2017.

- Office of Financial Research. “Central Counterparty Default Waterfalls and Systemic Loss.” 2020.

- New York University Stern School of Business. “Liquidity Management in Central Clearing ▴ How the Default Waterfall Can Be Improved.” 2022.

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures & International Organization of Securities Commissions. “Principles for financial market infrastructures.” Bank for International Settlements, 2012.

- Financial Stability Board, CPMI & IOSCO. “Analysis highlights need to continue work on CCP financial resources.” 2022.

Reflection

The analysis of a CCP’s internal incentive structure moves beyond a purely academic exercise. It compels a critical examination of the foundational architecture upon which market participants build their own risk management frameworks. The degree to which a CCP successfully aligns its profit motives with its stability mandate has direct, tangible consequences for every firm that relies on it for clearing. The integrity of the entire system is predicated on this alignment.

Therefore, the crucial question for any institutional participant is not simply “Does a conflict of interest exist?” but rather, “How does our own operational framework account for the specific ways this conflict is managed at our CCPs?” Understanding the size of your CCP’s skin in the game, the mechanics of its default waterfall, and the governance of its risk committees are essential inputs for your own firm’s systemic risk model. The knowledge gained here is a component of a larger intelligence system, one that transforms a theoretical market structure problem into a practical, actionable element of your firm’s strategic resilience.

Glossary

Central Counterparty

Financial Stability

Profit Maximization

Default Waterfall

Initial Margin

Default Fund Contributions

Surviving Members

Clearing Members

Risk Management

Systemic Risk

Default Fund