Concept

The inquiry into whether a sovereign debt crisis could overwhelm a central counterparty’s (CCP) default waterfall is an examination of the financial system’s core architecture. At its heart, this is a question of systemic resilience. A CCP is designed as a firewall, an entity engineered to absorb the failure of one of its members and prevent contagion. It achieves this by concentrating and managing counterparty credit risk.

The system functions by substituting the CCP as the counterparty to every trade, effectively neutralizing the direct credit risk between individual market participants. This concentration, however, creates a new potential point of failure, one of immense scale. The default waterfall is the sequential, pre-defined mechanism designed to handle a member’s failure without jeopardizing the CCP itself or the broader market.

A sovereign debt crisis introduces a unique and potent stressor into this system. High-quality sovereign bonds are the bedrock of financial collateral; they are the assets posted as margin to secure trading positions within the CCP. A crisis that undermines the value and liquidity of these specific instruments attacks the very foundation of the CCP’s risk management framework. The scenario presents a “wrong-way risk” of the highest order ▴ the financial health of the clearing members deteriorates for the same reason that the collateral they have posted to the CCP is losing its value.

This dual-front assault is the primary vector through which a sovereign debt crisis can initiate a cascade. The event tests not just the pre-funded resources of the waterfall but the stability of the surviving members who are contractually obligated to provide further support, all while they are likely experiencing the same systemic stress. The question, therefore, moves from the failure of a single member to the potential for a correlated failure across multiple members, driven by a common, systemic shock to the most trusted class of financial assets.

The Architecture of Systemic Risk Mitigation

Central counterparties represent a fundamental architectural shift in financial markets, designed to solve the problem of bilateral counterparty risk that became acutely visible during the 2008 financial crisis. By standing between a buyer and a seller in every transaction through a process called novation, a CCP becomes the “buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer.” This structure provides two immediate benefits. First, it allows for the multilateral netting of exposures, which significantly reduces the total volume of obligations and collateral required in the system.

Second, it standardizes and centralizes risk management, replacing a complex and opaque web of bilateral relationships with a single, highly regulated hub. This hub is responsible for establishing and enforcing risk controls for all its members.

The core of this risk management is the collection of margin.

- Initial Margin (IM) is the collateral posted by a clearing member to the CCP to cover potential future losses in the event of that member’s default. It is a forward-looking risk measure calculated to cover a specified confidence interval of potential price moves over a set period.

- Variation Margin (VM) is exchanged daily, or even intraday, to settle the profits and losses on a member’s open positions. This prevents the accumulation of large, unsecured exposures over time.

This margining system is the first line of defense. The concentration of risk within the CCP, however, means that its failure would be a catastrophic event, potentially causing far greater disruption than the failure of a single member in a purely bilateral system. Recognizing this, regulators and CCPs have engineered the default waterfall, a layered defense system designed to absorb losses in a sequential and predictable manner. The integrity of this waterfall is paramount to financial stability.

What Is the Role of Sovereign Debt as Collateral?

Sovereign debt, particularly from highly-rated governments, is considered the premier source of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) in the global financial system. Its role as collateral is foundational for several reasons. Central banks accept it in their open market operations, it is a key asset in repurchase agreements (repos), and, most importantly for this context, it is a primary form of initial margin accepted by CCPs.

CCPs require initial margin to be in the form of cash or assets that are both secure and highly liquid, enabling the CCP to seize and liquidate them quickly in the event of a default. Sovereign bonds have historically met these criteria perfectly.

A crisis of confidence in sovereign debt directly translates into a crisis of confidence in the collateral underpinning the cleared derivatives market.

The system’s reliance on this asset class creates a deep, structural vulnerability. A sovereign debt crisis, characterized by a rapid decline in the market value of a country’s government bonds and a seizure in their liquidity, strikes at the heart of the CCP’s risk management. The value of the initial margin posted by clearing members falls, prompting margin calls from the CCP.

To meet these calls, members may need to sell assets, including the very sovereign bonds that are falling in price, creating a self-reinforcing downward spiral. This procyclical effect is a key mechanism through which a sovereign debt crisis can amplify systemic stress.

Strategy

Analyzing the strategic interplay between a sovereign debt crisis and a CCP’s default waterfall requires a systems-thinking approach. The process is not a single event but a chain reaction, where each stage amplifies the stress on the next. The strategic vulnerabilities can be understood by dissecting the transmission channels from the initial sovereign shock to the potential exhaustion of the CCP’s entire loss-absorbing structure.

The Initial Shock and Procyclical Feedback

The sequence begins with a catalyst that shatters confidence in a sovereign’s ability to service its debt. This could be a ratings downgrade, a failed bond auction, or a political crisis. The immediate consequence is a sharp repricing of that sovereign’s bonds.

This is the initial shock. Its strategic importance lies in its dual impact on the balance sheets of major financial institutions, which are typically the largest clearing members of a CCP.

- Direct Balance Sheet Impact ▴ Major banks hold substantial amounts of sovereign debt as part of their liquidity buffers and investment portfolios. A price collapse directly erodes their capital base.

- Collateral Devaluation Impact ▴ The same banks use these sovereign bonds as collateral to post initial margin at CCPs. As the value of this collateral falls, the CCP’s risk models will register an exposure. The CCP will then issue a margin call, demanding additional collateral to cover the shortfall.

This creates a powerful procyclical feedback loop. The demand for additional high-quality collateral occurs at the precise moment its supply is effectively shrinking and the clearing members’ capacity to provide it is weakest. This is further exacerbated by the risk-sensitive nature of CCP margin models.

Increased market volatility, a hallmark of any crisis, causes the models to demand even higher levels of initial margin, intensifying the liquidity strain on members. This process is depicted in the table below, illustrating how a volatility shock translates into increased margin requirements.

| Market State | Observed Volatility | Value-at-Risk (VaR) Multiplier | Required Initial Margin (Illustrative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 2% | 1.5x | $100 million |

| Stressed | 8% | 2.5x | $400 million |

| Crisis | 20% | 4.0x | $1,600 million |

As the table shows, a spike in market volatility leads to a non-linear increase in initial margin requirements. This is an intentional design feature to protect the CCP, but during a systemic crisis, it can trigger a liquidity drain that destabilizes the very members the CCP is meant to protect. Firms scrambling for liquidity may be forced to sell assets into a falling market, further depressing prices and amplifying the crisis.

The Clearing Member Default

A sufficiently severe sovereign crisis can push one or more major clearing members toward insolvency. The combination of direct losses on bond holdings and the immense liquidity pressure from CCP margin calls can become untenable. The default of a major clearing member is the event that activates the CCP’s default waterfall. At this point, the CCP’s primary objective shifts from risk prevention to loss management.

The CCP seizes the defaulting member’s entire portfolio of cleared trades and their posted initial margin. The CCP is now exposed to the market risk of this portfolio and must act to neutralize it, typically by auctioning the positions off to the surviving clearing members or hedging them in the open market.

The failure of a clearing member transforms the CCP’s function from a risk-neutral administrator to a direct bearer of market risk.

The critical challenge during a sovereign debt crisis is that the defaulting member’s portfolio is likely to be heavily concentrated in instruments correlated with the sovereign’s health (e.g. interest rate swaps, credit default swaps on the sovereign or related entities). Hedging or auctioning these positions in a panicked and illiquid market is extraordinarily difficult. The bids received may be low, resulting in a loss that far exceeds the initial margin posted by the now-defaulted member. This is when the cascade through the default waterfall truly begins.

How Does the Waterfall Propagate the Crisis?

The default waterfall is designed to mutualize losses that exceed the defaulter’s dedicated resources. While this design protects the CCP, it also acts as a direct transmission channel for stress to the surviving clearing members. The sequence is as follows:

- Defaulter’s Resources Exhausted ▴ The losses from liquidating the defaulter’s portfolio first consume their initial margin and their contribution to the default fund.

- CCP’s Capital Consumed ▴ Next, a slice of the CCP’s own capital, known as “skin-in-the-game,” is used. This is typically a small portion of the total resources.

- Mutualized Fund Depleted ▴ The CCP then begins to draw on the default fund contributions of all the surviving, non-defaulting members. This is the first point where the defaulter’s losses are directly imposed on the “healthy” members.

During a sovereign debt crisis, this mutualization is particularly dangerous. The surviving members are already weakened by the same systemic shock that caused the initial default. They are experiencing losses on their own bond holdings and facing their own heightened margin calls. The depletion of their default fund contributions at the CCP represents another direct capital loss, further weakening their financial position.

If the losses are large enough to exhaust the entire pre-funded default fund, the CCP can make further “cash calls” or “assessment calls,” demanding additional funds from the surviving members. This is the final stage of the cascade, where the stress is no longer contained and is actively spreading, potentially causing a second, and then a third, clearing member to fail. This is how a single default can cascade into a systemic collapse that overwhelms the CCP structure entirely.

Execution

The execution of a CCP’s default management process during a sovereign debt crisis is a high-stakes operational procedure where financial architecture is tested in real-time. Understanding this process requires a granular analysis of the default waterfall’s mechanics and the quantitative impact of a correlated, systemic shock. The core challenge is managing a default where the value of both the defaulter’s positions and their posted collateral are collapsing simultaneously.

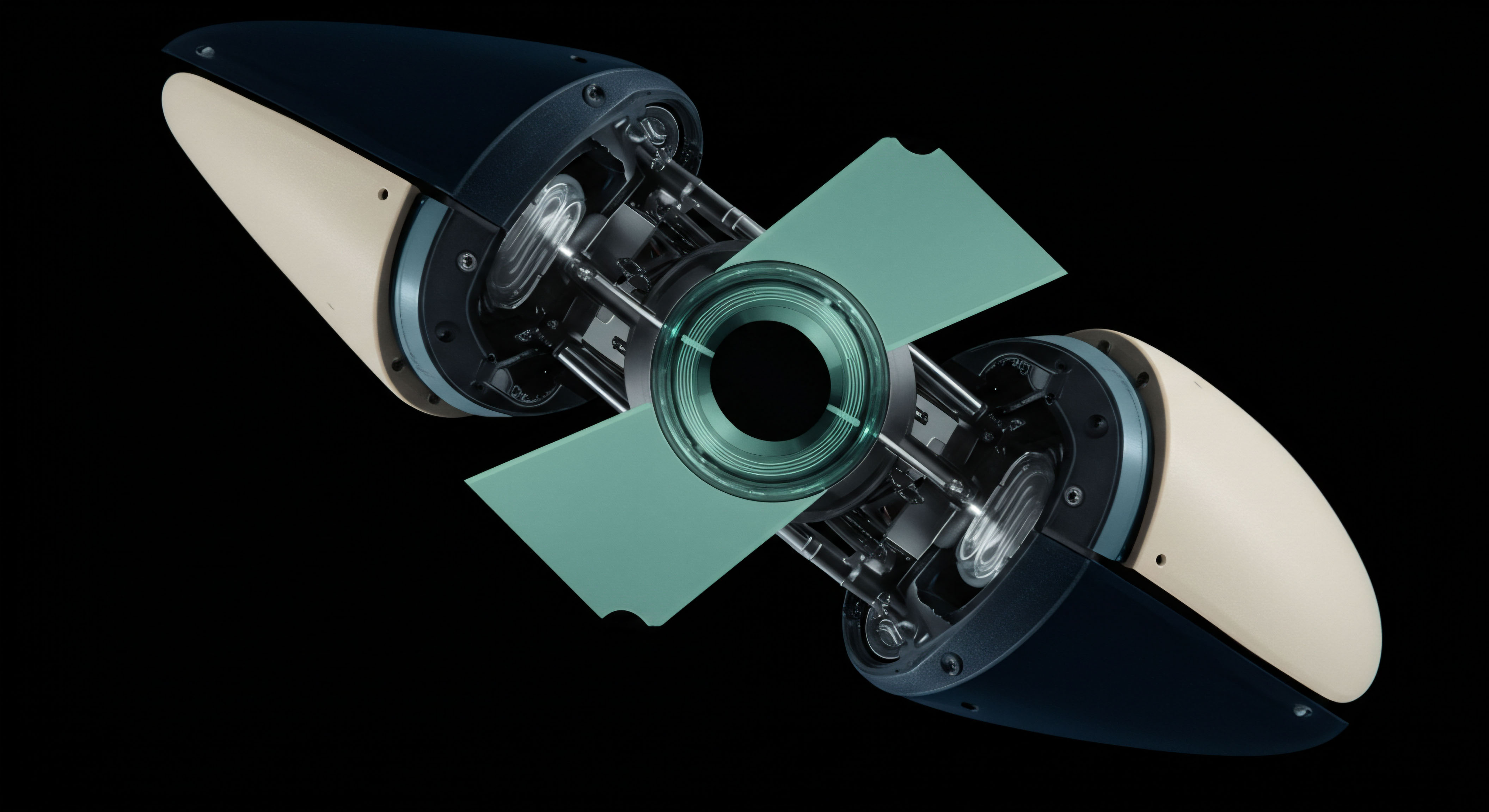

Anatomy of the Default Waterfall Sequence

A CCP’s default waterfall is a rigidly defined, sequential application of financial resources to cover losses stemming from a member’s failure. Its structure is designed to ensure transparency and predictability in a crisis, but its effectiveness hinges on the assumption that member defaults are largely idiosyncratic events. A systemic crisis challenges this premise. The following list details the typical layers of the waterfall, which function as the CCP’s operational playbook for loss allocation.

- Initial Margin of the Defaulting Member ▴ This is the first layer. The CCP immediately seizes the initial margin posted by the member that has failed. This collateral is specific to the defaulter and is meant to cover the vast majority of potential losses under normal market conditions.

- Default Fund Contribution of the Defaulting Member ▴ The second line of defense is the defaulter’s own contribution to the mutualized default fund. This resource is also exhausted before any losses are shared among other parties.

- CCP “Skin-in-the-Game” (SITG) ▴ The third layer involves the CCP contributing a portion of its own capital. This demonstrates that the CCP has a direct financial stake in the effectiveness of its own risk management. However, the amount is typically modest compared to the total size of the default fund.

- Default Fund Contributions of Surviving Members ▴ This is the critical mutualization stage. Once the defaulter’s resources and the CCP’s SITG are depleted, the CCP begins to allocate the remaining losses against the default fund contributions of the non-defaulting members.

- Unfunded Assessment Rights (Cash Calls) ▴ If losses exceed the entirety of the pre-funded resources (all margin and the entire default fund), the CCP has the right to make additional capital calls on its surviving members. This is the point where the pre-funded defenses have failed, and the CCP is drawing on the current liquidity of its already-stressed members.

- Resolution Tools ▴ Should the cash calls be insufficient or if they would trigger further defaults, the CCP enters its end-of-waterfall scenario. Tools at this stage can include variation margin gains haircutting (capping the profits paid out to members with winning trades) or even the forced tear-up of contracts, a measure of last resort that signals a partial or total failure of the clearing system.

Quantitative Modeling of a Waterfall Cascade

To operationalize this concept, consider a hypothetical scenario. A major CCP has 20 clearing members. A severe sovereign debt crisis in a key country (e.g. Italy or Japan) causes the default of one of its largest members (Defaulter A).

The CCP’s task is to close out Defaulter A’s portfolio, which has a massive, unhedged exposure to the crisis. The resulting loss from this close-out is $15 billion. The table below models the depletion of the CCP’s default waterfall resources.

| Waterfall Layer | Available Resources | Loss Applied | Remaining Resources | Systemic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defaulter A’s Initial Margin | $8.0 billion | $8.0 billion | $0 | No contagion yet; defaulter’s resources absorb initial loss. |

| Defaulter A’s Default Fund Contribution | $1.0 billion | $1.0 billion | $0 | Full use of defaulter’s dedicated funds. |

| CCP’s Skin-in-the-Game | $0.5 billion | $0.5 billion | $0 | CCP capital is hit, signaling a serious event. |

| Surviving Members’ Default Fund | $19.0 billion | $5.5 billion | $13.5 billion | Direct capital loss for all 19 surviving members. Confidence erodes. |

| Total Loss So Far | $28.5 billion | $15.0 billion | $13.5 billion | The pre-funded waterfall has been breached. |

In this scenario, the initial loss of $15 billion has been covered. However, it has consumed all of the defaulter’s resources, the CCP’s own capital contribution, and a significant portion ($5.5 billion) of the mutualized default fund. This $5.5 billion loss is now spread across the 19 surviving members. Now, assume the crisis deepens, and a second, correlated default (Defaulter B) occurs, generating another $12 billion in losses.

The remaining default fund of $13.5 billion is now further depleted, leaving only $1.5 billion. The CCP is now on the brink of exhausting its pre-funded resources entirely. Any further losses would trigger cash calls on the surviving 18 members, who are themselves facing extreme market stress. This is the mechanism of the cascade in action.

What Is the Impact of a Sovereign Collateral Crisis?

The situation is critically worsened by the nature of the collateral itself. In a sovereign debt crisis, the CCP faces a “wrong-way risk” where the member’s default is correlated with the declining value of the collateral they posted. For instance, an Italian bank defaulting due to a crisis in Italian government debt will have posted large amounts of that same Italian debt as initial margin.

The failure of a CCP is no longer a theoretical tail risk but a plausible outcome when its foundational collateral is the source of the systemic crisis.

The CCP’s ability to liquidate this collateral at its pre-crisis valuation is compromised. It must sell these devalued bonds into a market with few buyers, realizing a recovery value far below what its risk models had assumed. This widens the loss from the default, accelerating the depletion of the waterfall.

The very asset intended to provide safety becomes a source of amplified risk, directly challenging the operational viability of the clearing system. The interconnectedness of the system means that stress in one CCP can also be transmitted to others, as major banks are often members of multiple CCPs globally, creating a potential for cross-CCP contagion.

References

- Arnsdorf, M. “Quantification of central counterparty risk.” Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions 5.3 (2012) ▴ 273-287.

- Cont, Rama. “Central clearing and systemic risk.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 9 (2017) ▴ 275-298.

- Duffie, Darrell, and Haoxiang Zhu. “Does a central clearing counterparty reduce counterparty risk?.” The Review of Asset Pricing Studies 1.1 (2011) ▴ 74-95.

- Glasserman, Paul, and Peyton Young. “Contagion in financial networks.” Journal of Economic Literature 54.3 (2016) ▴ 779-831.

- Ghamami, S. “A theory of collateral requirements for central counterparties.” American Economic Association, 2019.

- Gurrola-Perez, Pedro. “Procyclicality of CCP margin models ▴ systemic problems need systemic approaches.” Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 902 (2020).

- Heath, A. Kelly, G. and Manning, M. “Central counterparties ▴ what are they, why are they important and what is the Bank’s role?.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Q3 (2013).

- Huang, Wenqian, and Előd Takáts. “Model risk at central counterparties ▴ Is skin-in-the-game a game changer?.” BIS Working Papers No. 866 (2020).

- Loon, Y. C. and Z. K. O. Papaoikonomou. “Central counterparty exposure in the credit default swap market.” Financial Analysts Journal 71.1 (2015) ▴ 46-61.

- Murphy, D. and P. Nahai-Williamson. “The procyclicality of initial margin.” Journal of Financial Market Infrastructures 3.2 (2014) ▴ 1-22.

- Pirrong, Craig. “The economics of central clearing ▴ theory and practice.” ISDA Discussion Papers Series 1 (2011).

- Singh, Manmohan. “Collateral, net settlement and systemically important financial institutions.” IMF Working Paper No. 11/68 (2011).

- Wendt, Froukelien. “Central counterparties ▴ addressing their too important to fail nature.” IMF Working Paper No. 15/21 (2015).

Reflection

The analysis of a CCP’s vulnerability to a sovereign debt crisis forces a reflection on a core architectural trade-off in modern finance. We have engineered systems that solve for bilateral counterparty risk by concentrating that risk into systemically important nodes. The default waterfall is the operational protocol designed to manage this concentrated risk. The resilience of this entire structure, however, is predicated on the integrity of its foundational assets, namely high-quality sovereign debt used as collateral.

When the source of a systemic shock is the very asset class intended to provide safety, the system’s internal logic is turned against itself. The event ceases to be a test of a single institution’s risk management and becomes a test of the entire market’s structural soundness. This prompts a critical question for any institutional participant ▴ How robust is our own operational framework against a correlated, systemic crisis?

The knowledge of the cascade mechanism is one component of a larger intelligence system. True resilience requires an operational framework that can anticipate and model liquidity and collateral pressures under such extreme, system-wide stress scenarios, where the established rules of safety and risk are fundamentally challenged.

Glossary

Sovereign Debt Crisis

Central Counterparty

Default Waterfall

Clearing Members

Risk Management

Surviving Members

Sovereign Debt

Central Counterparties

Counterparty Risk

Clearing Member

Initial Margin

Default Fund

Skin-In-The-Game

Default Fund Contributions

Cash Calls