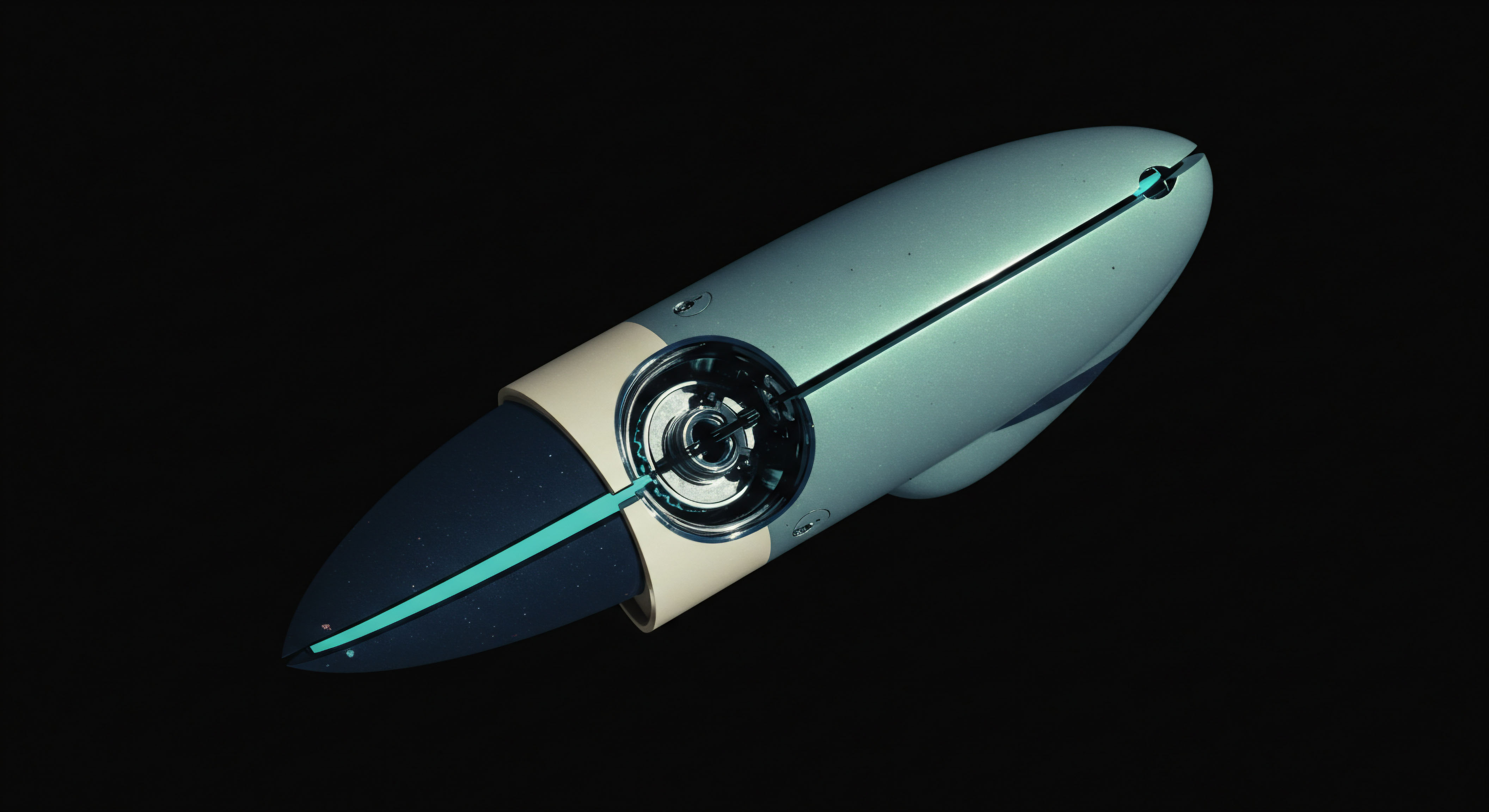

Concept

The architecture of financial stability within centrally cleared markets rests on a sophisticated alignment of incentives. A critical component of this system is the concept of “skin in the game” (SITG), which refers to the portion of a central counterparty’s (CCP) own capital that is put at risk to cover losses from a clearing member’s default. This mechanism is designed to ensure that the CCP’s risk management protocols are robust, as its own financial resources are on the line. The presence of SITG provides a powerful incentive for the board and senior management of a CCP to take risk management seriously.

It acts as a disciplining function, compelling the CCP to enforce prudent initial margin requirements and maintain a resilient default waterfall. The default waterfall is the sequential process through which losses are allocated, starting with the defaulted member’s assets, then the CCP’s SITG, and finally the mutualized guarantee fund contributed by non-defaulting members.

The prevailing logic supports SITG as a vital safeguard. It creates a buffer that protects surviving clearing members from immediately bearing the full cost of a peer’s failure. In principle, this alignment of interests between the CCP and its members should foster a more secure clearing environment. The CCP, motivated by self-preservation, is expected to police risk-taking among its members, while members, in turn, are incentivized to monitor the CCP’s risk management practices.

This symbiotic relationship is the theoretical bedrock of the modern clearing system. The structure of the default waterfall, with SITG positioned at a specific layer, is a deliberate piece of financial engineering intended to balance these interests and fortify the system against catastrophic failure.

An excessive amount of skin in the game can distort the delicate balance of incentives within a clearinghouse, potentially leading to risk aversion that stifles market growth or, conversely, to a mispricing of risk that jeopardizes financial stability.

However, a critical question arises from this framework ▴ can a CCP have too much skin in the game? The answer is a complex one, with significant implications for market structure and stability. An excessively large SITG contribution can paradoxically create a new set of negative incentives. If the CCP’s capital contribution to the default waterfall becomes disproportionately large, it can dilute the incentives for clearing members to participate actively in the default management process.

This is because the members’ own contributions to the mutualized guarantee fund are further insulated from loss, reducing their imperative to engage in the critical work of auctioning a defaulted member’s portfolio. The result can be a less efficient and more costly default management process, ultimately borne by the entire market.

Furthermore, the ownership structure of the CCP introduces another layer of complexity. Many clearinghouses have demutualized, transitioning from member-owned cooperatives to for-profit, investor-owned corporations. In this model, the interests of shareholders (who desire profit maximization) and clearing members (who desire risk minimization and low costs) can diverge. An excessive SITG requirement in a for-profit CCP could lead to several adverse outcomes.

The CCP might become overly conservative in its risk management, setting prohibitively high margin requirements that stifle liquidity and increase the cost of clearing for all participants. Alternatively, to attract business, it might underprice risk in certain products, knowing that its large SITG contribution provides a seemingly robust buffer, while the long-tail risks are still ultimately socialized among the members. This creates a moral hazard, where the CCP reaps the rewards of increased volume while the systemic risk to the clearing ecosystem grows.

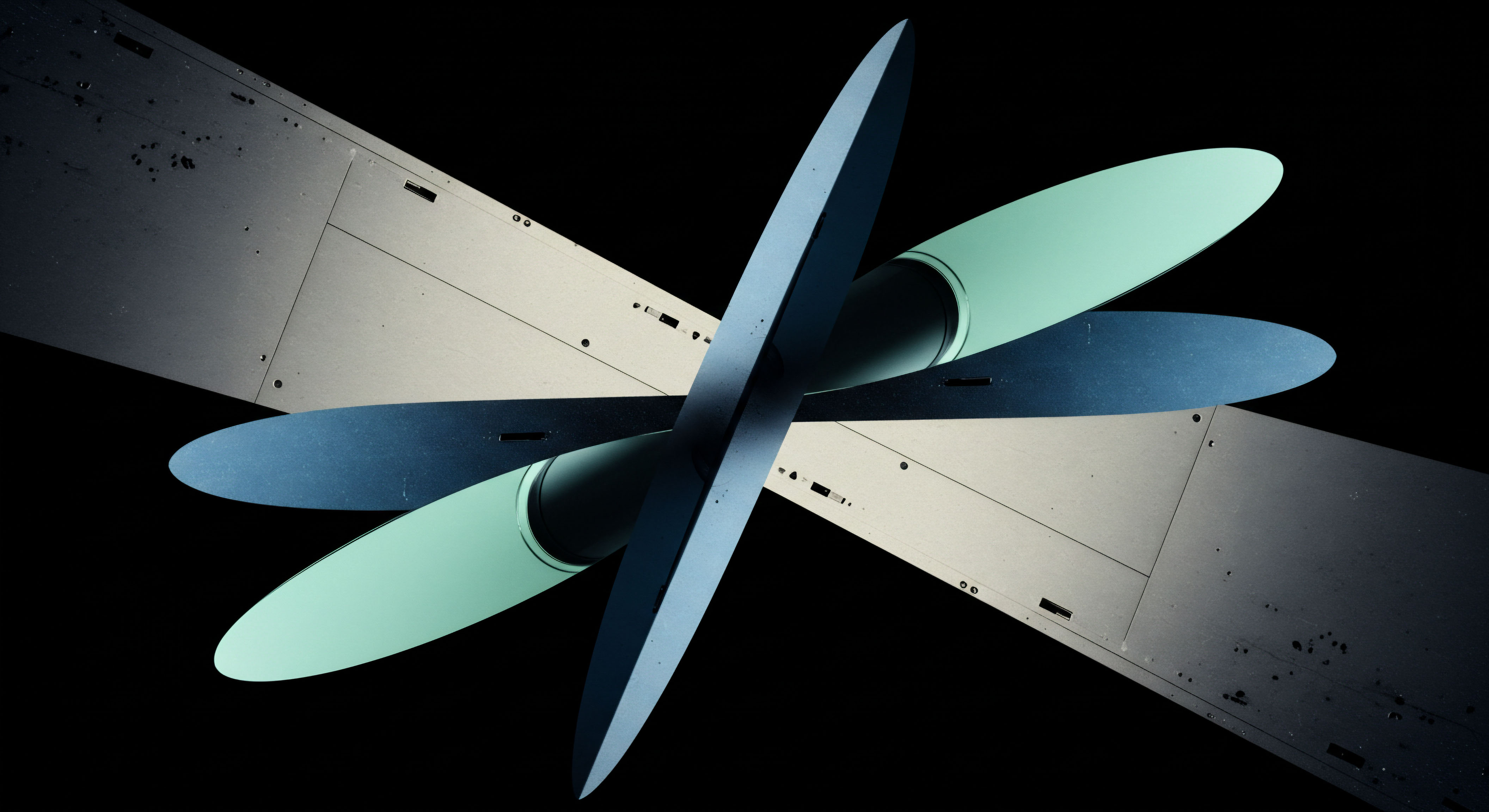

Strategy

Strategically, the calibration of a CCP’s skin in the game is a delicate balancing act. The goal is to optimize the incentive structure for all market participants ▴ the CCP, its clearing members, and their clients ▴ to ensure the resilience of the clearing system without introducing unintended consequences. An imbalance in either direction, too little or too much SITG, can have profound strategic implications for the functioning of financial markets. The debate over the appropriate level of SITG is, in essence, a debate about the optimal distribution of risk and responsibility within the clearing ecosystem.

The Moral Hazard of Excessive SITG

A primary strategic concern with an overly large SITG is the creation of moral hazard among clearing members. When a CCP’s contribution to the default waterfall is substantial, it can numb the risk sensitivity of its members. The members’ own capital is further down the loss-allocation chain, leading to a diminished sense of urgency in monitoring both the CCP’s risk management practices and the risk profiles of their fellow members. This can manifest in several ways:

- Reduced Participation in Default Management ▴ The default management process, which often involves auctioning the portfolio of a defaulted member, relies on the active and aggressive bidding of surviving members. If their own capital is not immediately at risk, they may be less inclined to bid competitively, leading to a less efficient auction and potentially larger losses for the CCP.

- Lax Scrutiny of CCP Operations ▴ Clearing members have a vested interest in ensuring their CCP operates with the highest standards of risk management. An excessive SITG can create a false sense of security, leading members to be less critical of the CCP’s margining models, stress testing methodologies, and technology infrastructure.

- Increased Appetite for Risk ▴ For some clearing members, a large SITG at the CCP level could be viewed as a subsidy for risk-taking. They may be tempted to take on riskier clients or engage in more speculative trading strategies, knowing that a significant portion of the potential losses would be absorbed by the CCP before their own guarantee fund contributions are touched.

What Is the Optimal Level of Skin in the Game?

Determining the optimal level of SITG is a complex exercise in quantitative risk management and game theory. There is no single answer, as the ideal amount depends on a variety of factors, including the size and complexity of the market being cleared, the number and diversity of clearing members, and the ownership structure of the CCP. However, some general principles can be applied:

- Proportionality ▴ The SITG should be large enough to be meaningful to the CCP, ensuring it has a strong incentive to manage risk prudently. A token amount would be ineffective. Conversely, it should not be so large as to dwarf the contributions of the clearing members, which would dilute their own incentives.

- Dynamic Calibration ▴ The optimal level of SITG may change over time as market conditions evolve. A static, one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to be effective. CCPs and their regulators should periodically review and adjust SITG requirements to reflect changes in market volatility, trading volumes, and the overall risk environment.

- Transparency ▴ The methodology for calculating and positioning the SITG within the default waterfall should be transparent to all market participants. This allows clearing members to accurately assess their own risk exposures and make informed decisions about their participation in the clearinghouse.

The strategic challenge lies in calibrating skin in the game to be a powerful incentive for the CCP without becoming a disincentive for its members.

The following table illustrates the strategic trade-offs associated with different levels of SITG:

| SITG Level | Positive Incentives | Negative Incentives |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Strong incentive for clearing members to monitor the CCP and each other. Active participation in default management. | Weak incentive for the CCP to manage risk prudently. Potential for under-margining and lax risk controls. |

| Optimal | Balanced incentives for both the CCP and its members. Strong risk management by the CCP, coupled with active monitoring and participation by members. | Difficult to determine and maintain. Requires ongoing calibration and a deep understanding of market dynamics. |

| High | Very strong incentive for the CCP to manage risk prudently. May lead to overly conservative risk management and high costs for members. | Moral hazard among clearing members. Reduced participation in default management. Potential for the CCP to become “too big to fail.” |

The Impact on Innovation and Competition

An often-overlooked consequence of excessively high SITG requirements is the potential to stifle innovation and competition in the clearing industry. A CCP with a very large amount of its own capital at risk may become extremely risk-averse, reluctant to clear new and innovative products, even if they would benefit the market. This can slow the pace of financial innovation and entrench the position of incumbent CCPs, making it more difficult for new entrants to compete.

The result is a less dynamic and potentially less efficient market structure. The challenge for regulators is to set SITG requirements at a level that promotes safety and soundness without creating undue barriers to entry or discouraging innovation.

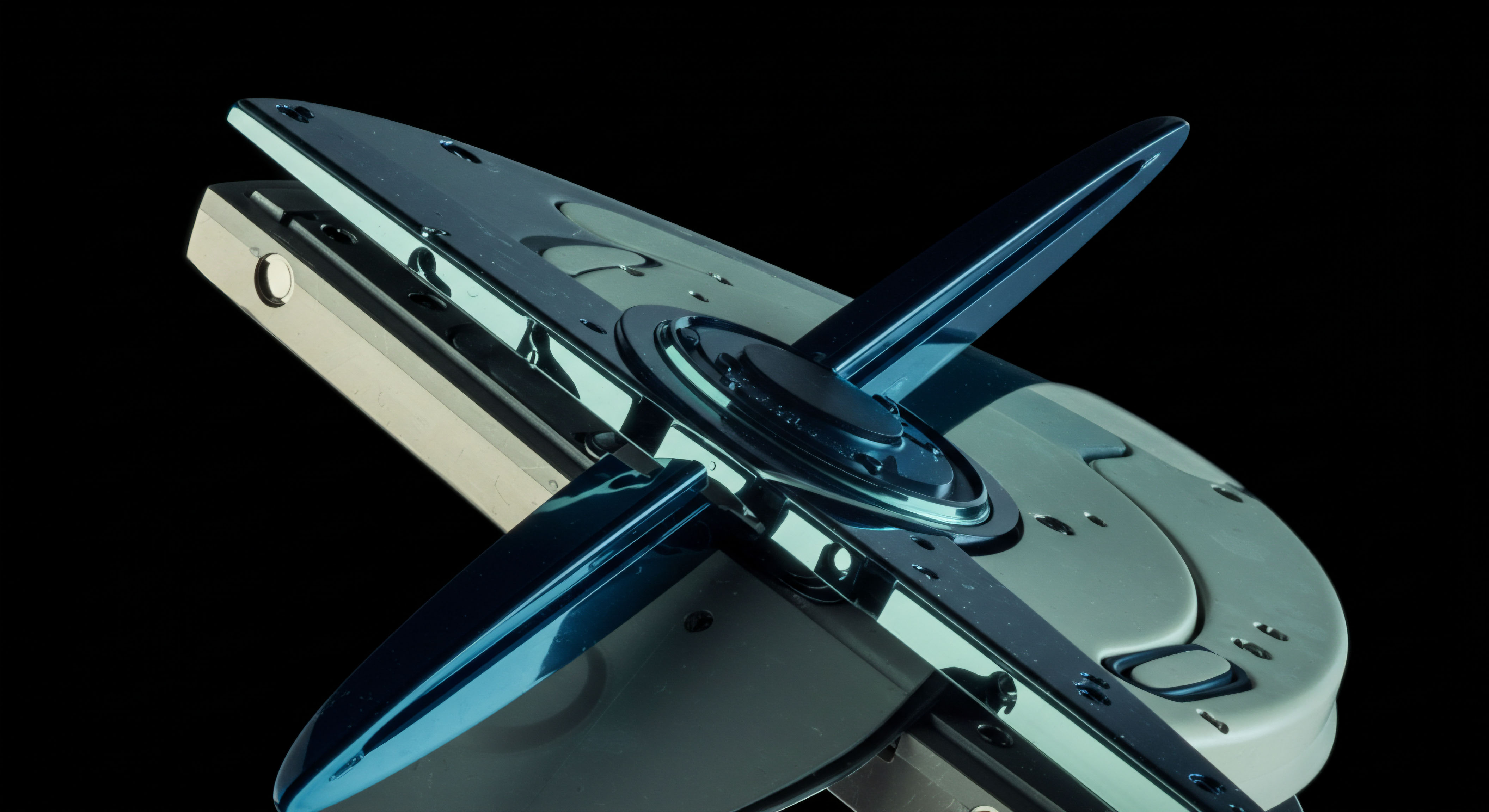

Execution

The execution of a “skin in the game” policy within a CCP’s operational framework is where the theoretical concepts of incentive alignment and risk management are translated into concrete actions and outcomes. The precise implementation of SITG, including its size, its position in the default waterfall, and the conditions under which it is replenished, has a direct and measurable impact on the behavior of both the CCP and its members. An improperly executed SITG strategy can lead to a range of adverse consequences, from operational inefficiencies to systemic crises.

How Can Excessive SITG Manifest in Practice?

The negative incentives created by an excessive SITG can manifest in several practical ways. A CCP facing a disproportionately large potential loss of its own capital may alter its operational behavior in ways that are detrimental to the market it serves. For example, it might become overly aggressive in its daily risk management, making frequent and pro-cyclical margin calls that exacerbate market stress.

During a crisis, a CCP with a large SITG might be tempted to delay the declaration of a default, hoping that market conditions will improve and allow the troubled member to recover, rather than triggering a loss of its own capital. This forbearance could ultimately increase the size of the loss and the risk to the entire system.

Conversely, a CCP with a very large SITG might be perceived by the market as having a “deep pocket,” leading to a different set of problems. Clearing members might be less diligent in their own risk management, assuming the CCP’s capital provides an unbreakable backstop. This could lead to a gradual erosion of risk discipline across the market, with members taking on more leverage and engaging in riskier trading strategies than they otherwise would. The result is a system that appears stable on the surface but is harboring hidden and growing vulnerabilities.

In the real world, the execution of an SITG policy determines whether it is a source of strength or a point of failure for a clearinghouse.

The following table outlines some of the potential negative operational outcomes of an excessive SITG and possible mitigation strategies:

| Operational Risk | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Default Management | Clearing members are less motivated to participate in the auction of a defaulted member’s portfolio, leading to lower recovery rates and higher losses for the CCP. | Introduce a second, smaller tranche of SITG that is only triggered after a portion of the members’ guarantee fund is used, realigning incentives for participation. |

| Pro-cyclical Margining | The CCP, fearing for its own capital, makes aggressive and frequent margin calls during periods of market stress, exacerbating volatility and liquidity shortages. | Implement through-the-cycle margining models that are less sensitive to short-term market fluctuations. Increase transparency around margin calculations. |

| Delayed Default Declaration | The CCP hesitates to declare a member in default, hoping the member will recover, which can increase the ultimate loss. | Establish clear and objective criteria for declaring a default, with independent oversight from regulators and a risk committee composed of clearing members. |

| Stifled Innovation | The CCP becomes overly conservative and refuses to clear new or complex products, even if they would benefit the market, for fear of incurring a loss. | Create a more flexible regulatory framework that allows for the phased introduction of new products with appropriate risk controls. Foster competition among CCPs. |

The Role of Governance and Regulation

Ultimately, the effective execution of an SITG policy depends on strong governance and intelligent regulation. The board of the CCP, its risk committee, and its regulators all have a crucial role to play in ensuring that SITG is calibrated and implemented in a way that promotes financial stability. This requires a deep understanding of the complex interplay of incentives within the clearing ecosystem and a willingness to adapt to changing market conditions.

For investor-owned CCPs, there is a particular need for robust governance structures to manage the inherent conflict between the interests of shareholders and the interests of clearing members. Independent directors, a strong and empowered risk committee with significant member representation, and vigilant regulatory oversight are all essential components of a well-functioning clearinghouse. The goal is to create a system of checks and balances that ensures the CCP is managed for the long-term health of the market, not just for the short-term profits of its shareholders.

References

- The World Federation of Exchanges. “A CCP’s skin-in-the-game ▴ Is there a trade-off?” 2020.

- Intercontinental Exchange. “The Importance of ‘Skin-in-the-Game’ in Managing CCP Risk.” 2020.

- Ghamami, Samim. “Skin in the Game ▴ Risk Analysis of Central Counterparties.” 2023.

- The Options Clearing Corporation. “Optimizing Incentives, Resilience and Stability in Central Counterparty Clearing.” 2020.

- Cerezetti, Sheila C. and Steven L. Schwarcz. “The Ownership of Clearinghouses ▴ When “Skin in the Game” Is Not Enough, the Remutualization of Clearinghouses.” Yale Journal on Regulation, 2020.

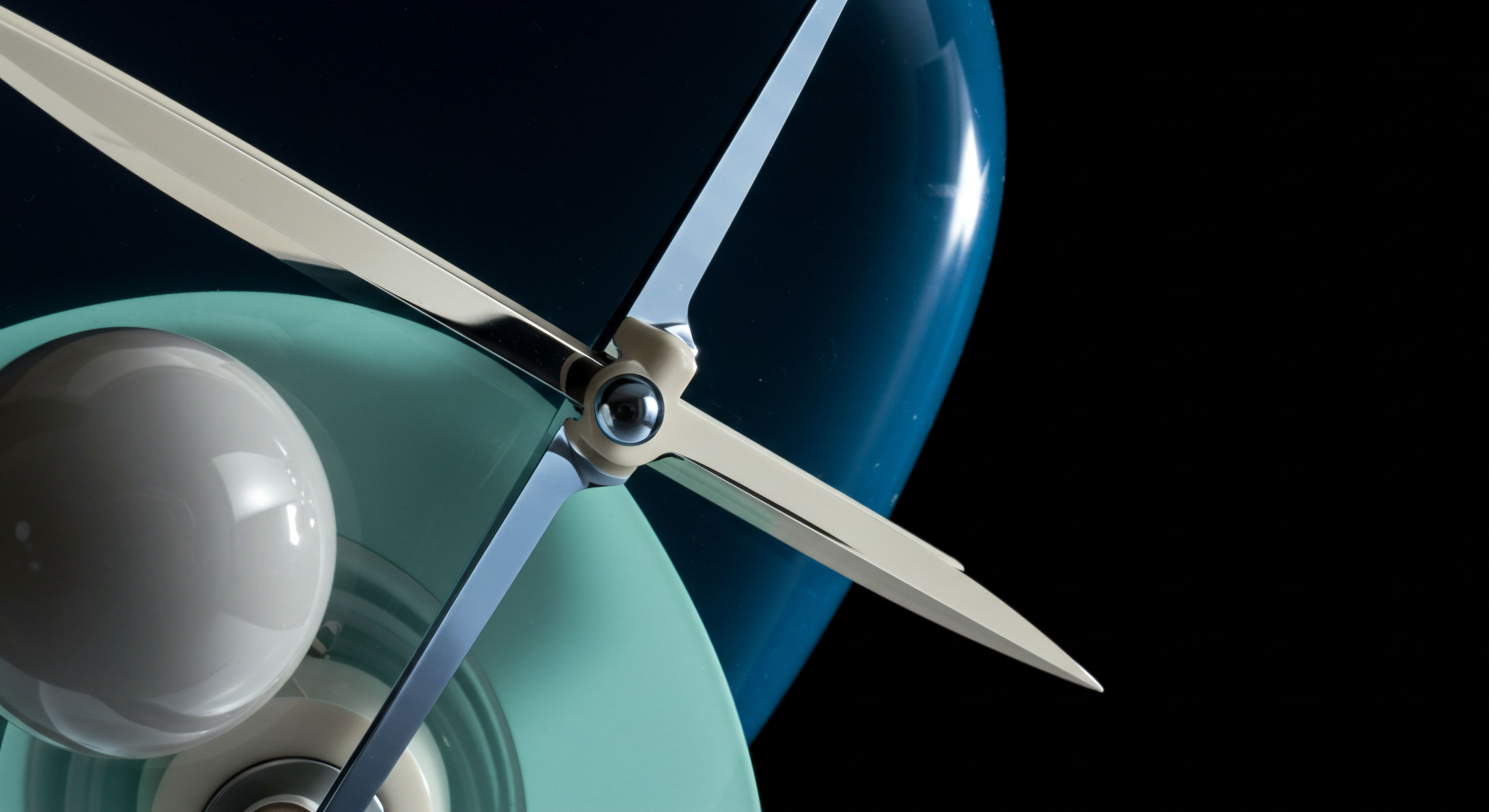

Reflection

The analysis of skin in the game within the context of central clearing is an inquiry into the very nature of financial architecture. It reveals that the mechanisms designed to ensure stability can, if improperly calibrated, become sources of systemic vulnerability. The question of how much risk a CCP should bear is a question of how we, as a market, choose to distribute responsibility and align incentives.

There is no perfect, static answer. The optimal solution is a dynamic equilibrium, constantly recalibrated in response to the evolving landscape of risk.

What Is the Ultimate Purpose of a Clearinghouse?

A clearinghouse is more than just a private utility; it is a public good, a critical piece of infrastructure upon which the stability of the financial system depends. Its design and operation must reflect this dual role. The debate over SITG is a reminder that the pursuit of private profit and the promotion of public good are not always perfectly aligned. It compels us to think critically about the governance structures, regulatory frameworks, and incentive mechanisms that are necessary to ensure our clearinghouses remain bastions of strength, even in the most turbulent of times.

As you consider your own operational framework, ask yourself how the incentives within your organization are aligned. Where are the points of potential conflict? Where are the hidden moral hazards? The principles that govern the design of a resilient clearinghouse ▴ proportionality, transparency, and a dynamic approach to risk management ▴ are the same principles that govern the design of any successful and enduring financial enterprise.

Glossary

Central Counterparty

Financial Stability

Default Waterfall

Guarantee Fund

Clearing Members

Risk Management

Default Management Process

Default Management

Systemic Risk

Moral Hazard

Moral Hazard among Clearing Members

Clearinghouse