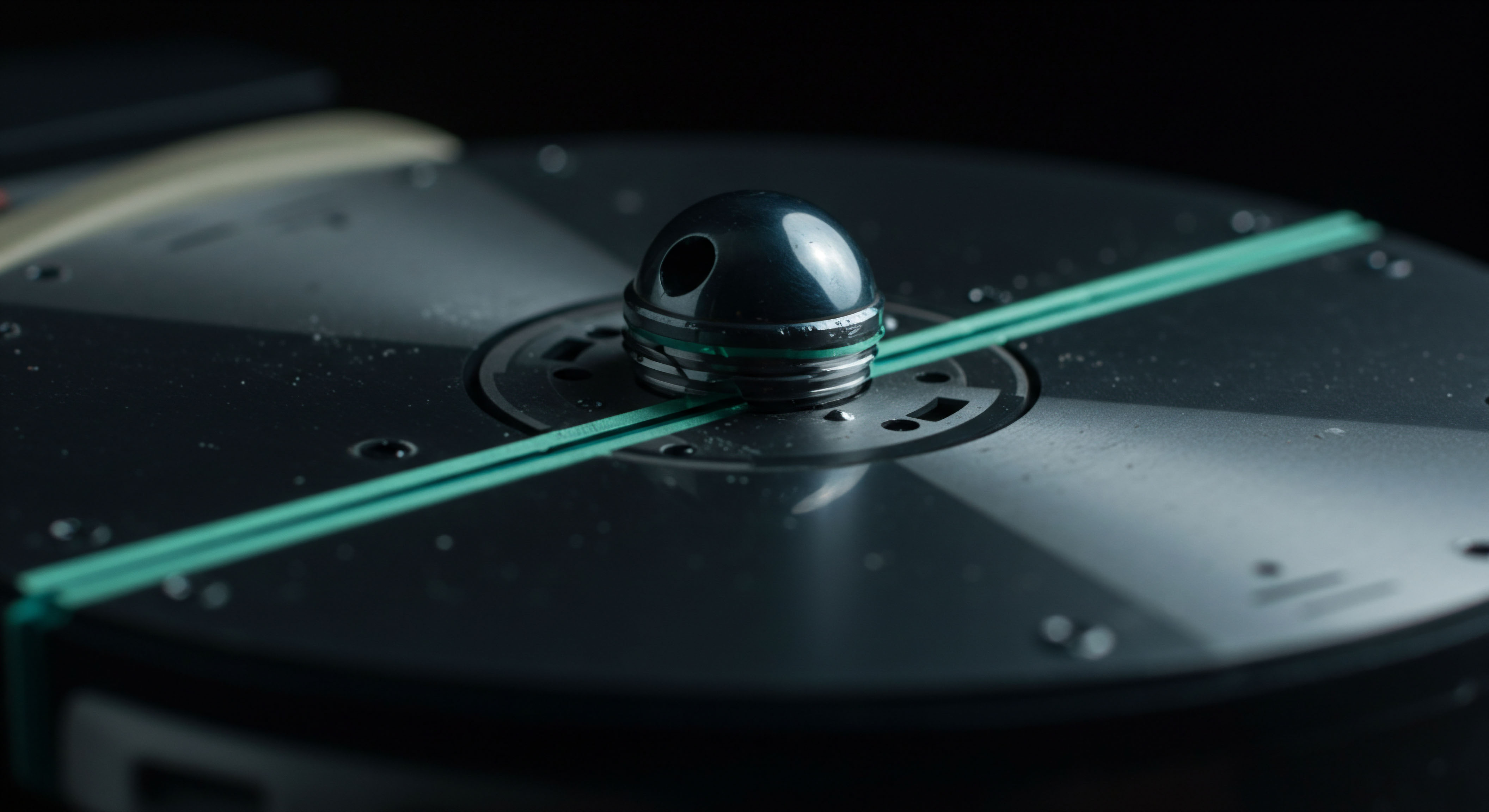

Concept

The architecture of international litigation is founded upon a jurisdiction’s rules of evidence disclosure. These protocols function as the operating system for dispute resolution, dictating the flow of information, the allocation of costs, and the very nature of strategic engagement. Understanding these systems is the foundational requirement for any effective litigation strategy. The core variance between these legal frameworks is a direct reflection of their underlying judicial philosophies.

One model prioritizes an exhaustive search for truth, assuming that near-total transparency is the most direct path to a just outcome. An alternative model elevates efficiency and privacy, operating on the principle that justice is best served by a focused, judge-led inquiry with minimal intrusion into a party’s affairs. A third approach seeks to synthesize these opposing views, creating a hybrid system that balances the competing demands of transparency and cost.

In any cross-border dispute, a party’s initial and most critical task is to map its strategy to the specific disclosure regime it confronts. The selection of a particular jurisdiction, where possible, becomes a primary strategic decision. The variance in these rules dictates everything from the initial budget to the ultimate probability of success. For instance, a litigant with a strong case but limited direct evidence may seek out a jurisdiction with broad discovery powers, intending to build its case using documents procured from the adversary.

Conversely, a party facing a speculative claim may favor a jurisdiction with restrictive disclosure rules to prevent the opponent from engaging in an exploratory, and costly, search for evidence. These initial calculations are fundamental to the entire litigation process. The rules are not passive administrative guidelines; they are active components of the strategic landscape.

The specific rules for discovery are heavily jurisdiction dependent, shaping the entire course of legal proceedings.

The obligation to disclose evidence is a critical and often burdensome stage of litigation. The scope of this duty is defined by the specific rules of the court in which the case is filed. In some jurisdictions, such as Queensland, Australia, the right to disclosure is automatic, meaning parties must exchange relevant documents as a standard part of the process. In other systems, including the Federal Court of Australia and numerous U.S. federal and state courts, a party must formally apply to the court for an order compelling disclosure.

This procedural distinction has profound strategic implications. An automatic disclosure requirement forces parties to be prepared with their evidence from the outset. A system requiring an application allows for strategic arguments about the scope and necessity of disclosure, creating an early battleground in the litigation.

The reach of disclosure extends to all documents within a party’s “possession, custody or power.” This definition is broad and encompasses documents held by agents, parent companies, or third parties over whom the litigant has a legal right to demand access. Even documents that are confidential or contain commercially sensitive information are typically discoverable if they are relevant to the issues in the case. Courts recognize that this process involves a significant invasion of privacy.

However, this concern is outweighed by the public interest in ensuring that justice is based on a complete factual record. This tension between confidentiality and the pursuit of truth is a central theme in the design and application of disclosure rules across all jurisdictions.

Strategy

Strategic planning in multi-jurisdictional litigation is an exercise in comparative systems analysis. The choice of legal system, when available, or the adaptation to an imposed one, is the single most important variable influencing cost, risk, and potential outcomes. The procedural rules governing the disclosure of evidence are the primary drivers of this strategic calculus.

Three principal models define the global landscape ▴ the expansive discovery model of the United States, the managed disclosure approach of England and Wales, and the highly restrictive systems common in civil law jurisdictions. Each model presents a unique set of strategic opportunities and challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Disclosure Regimes

The strategic implications of each disclosure model are best understood through a direct comparison of their core features. The American system, governed by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP), is designed for maximum informational access. The English system, under its Civil Procedure Rules (CPR), particularly the disclosure pilot scheme in Practice Direction 57AD, represents a move toward proportionality and judicial management. Civil law systems, by contrast, operate on an entirely different philosophy, where the parties, not the court, are primarily responsible for assembling their own evidence.

| Feature | United States (FRCP) | England & Wales (CPR PD57AD) | Civil Law (Exemplar) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope of Disclosure | Broadly defined as any non-privileged matter relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case. | Limited to specific models of “Extended Disclosure” agreed upon by the parties or ordered by the court, focusing on key issues. | Extremely limited; no broad pre-trial discovery. Parties submit documents they intend to rely on. |

| Initiation of Process | Parties exchange initial disclosures automatically and can then serve broad discovery requests. | Parties must cooperate on a “Disclosure Review Document” and agree on the scope of disclosure, with court oversight. | No formal discovery process. The judge may request specific documents during proceedings. |

| Key Mechanisms | Depositions (oral testimony under oath), interrogatories (written questions), requests for production of documents. | Disclosure limited to documents. No depositions. Emphasis on cooperation and technology to manage data. | No pre-trial depositions or interrogatories. Evidence is presented at hearings. |

| Cost Allocation | Each party generally bears its own costs, regardless of the outcome. | The losing party typically pays a significant portion of the winner’s legal costs (“costs follow the event”). | Costs are often fixed by statute and are relatively low. The loser pays the winner’s costs. |

| Judicial Philosophy | Truth is best found through a wide-ranging, party-driven search for evidence. | A balance between truth-seeking and proportionality, with active judicial management to control costs. | The judge leads the inquiry, and parties are expected to present their own cases. Efficiency is paramount. |

Strategic Implications of the American System

The U.S. discovery process is a powerful strategic weapon. Its breadth allows litigants to request vast amounts of information, including internal emails, reports, and electronic data that might lead to admissible evidence. This creates a dynamic where a plaintiff can file a lawsuit with a plausible claim and then use the discovery process to find the evidence needed to prove it. The strategic objective often becomes imposing significant costs on the opposing party.

The sheer expense of collecting, reviewing, and producing millions of documents can pressure a defendant into a settlement, regardless of the merits of the underlying case. This is amplified by the “American Rule” on costs, where each side pays its own legal fees, removing the deterrent of potentially having to pay the winner’s expenses.

What Are the Primary Goals in US Discovery?

The strategic goals within the American discovery framework extend beyond simple evidence gathering. A primary objective is often to gain leverage. By making discovery requests that are expensive and time-consuming to fulfill, a party can drain an opponent’s resources and resolve. Another key goal is to explore the opponent’s case in its entirety, identifying weaknesses and potential lines of attack.

The deposition process, unique to the U.S. system, is a critical tool for this. It allows lawyers to question opposing parties and key witnesses under oath before trial, locking in their testimony and assessing their credibility. This pre-trial examination is invaluable for shaping trial strategy and evaluating settlement offers.

The English Approach a Managed Strategy

The English system offers a “middle way” between the American and civil law extremes. The introduction of Practice Direction 57AD has shifted the focus from broad disclosure to a more tailored and cooperative process. Parties are now required to engage with each other at a very early stage to identify the key issues in dispute and agree on a proportional scope of disclosure. This forces a strategic discipline that is absent in the U.S. system.

A litigant cannot simply launch a wide-ranging fishing expedition. Instead, they must articulate precisely what categories of documents are needed and why they are relevant to the agreed-upon issues. The strategic advantage here lies in early case assessment and skillful negotiation. A party that can clearly define the issues in its favor can significantly limit the scope, and therefore the cost, of disclosure.

The English system is a middle way, with court-managed disclosure but significant costs of the process and awards of costs to the successful party.

The “loser pays” cost rule is a powerful strategic consideration in the English system. The risk of having to cover the opponent’s legal fees, which can be substantial, discourages speculative litigation. It forces parties to make a cold, hard assessment of their chances of success before proceeding.

This creates a more cautious and calculated strategic environment. The objective is to conduct the litigation as efficiently as possible while positioning the case to either win at trial or achieve a favorable settlement where the other side contributes to costs.

Navigating Foreign Blocking Statutes

A significant strategic challenge in international litigation arises from “blocking statutes.” These are laws enacted by foreign governments to prevent their citizens or companies from complying with discovery requests from other countries, particularly the United States. For example, a French company sued in a U.S. court may be ordered to produce certain documents under the FRCP, while French law prohibits their disclosure. This places the company in a “catch-22” situation ▴ comply with the U.S. court order and face penalties in France, or comply with French law and face sanctions in the U.S. for failing to produce evidence.

Strategically, the existence of a blocking statute can be used both defensively and offensively. A defendant may use it to argue for a protective order to limit the scope of discovery. A plaintiff, on the other hand, may need to develop strategies to obtain the necessary information through alternative means, such as letters rogatory or other international legal assistance treaties. The key is to understand that these conflicting legal obligations are a foreseeable part of the strategic landscape in cross-border disputes and must be addressed proactively.

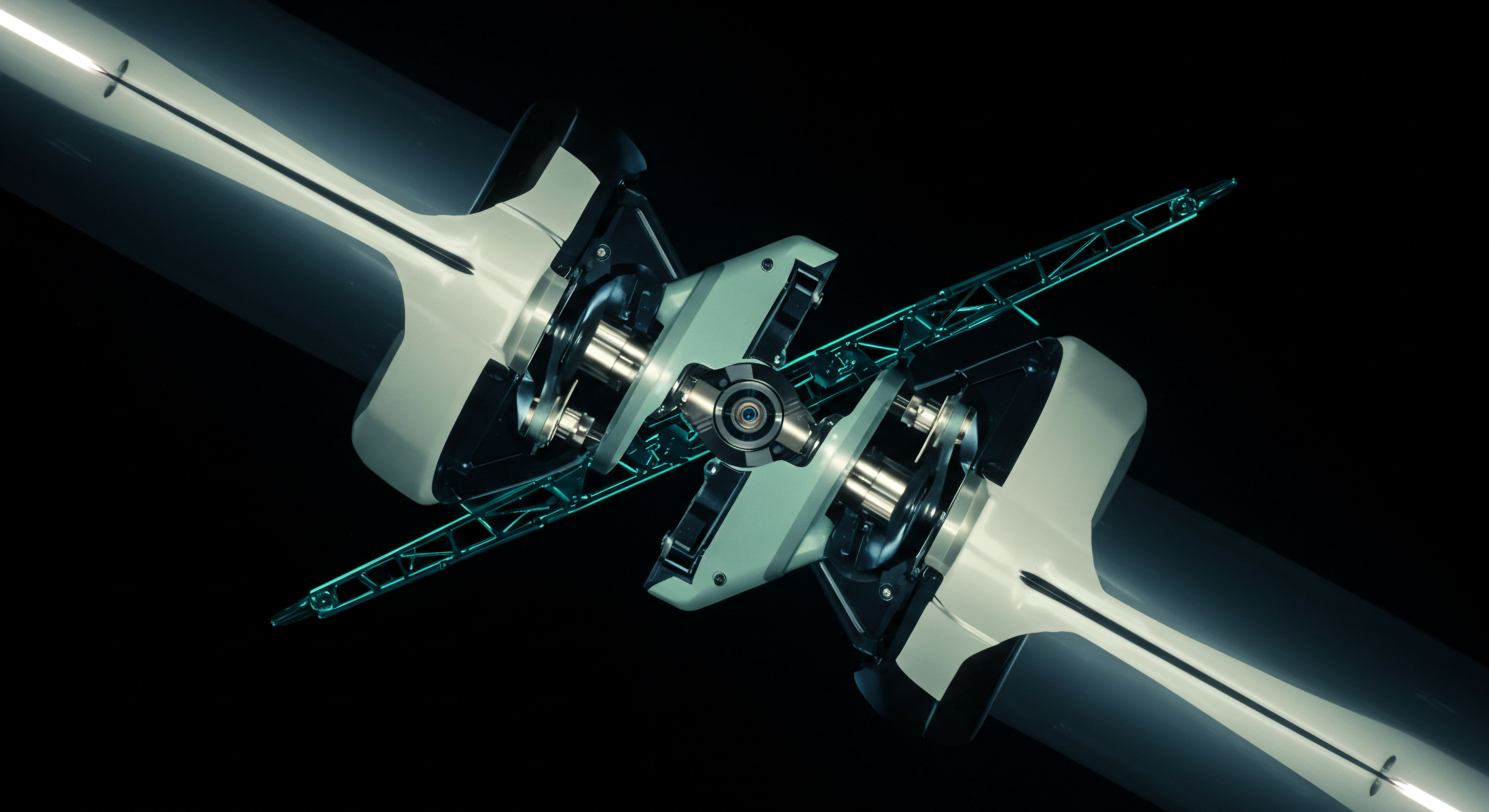

Execution

Executing a litigation strategy across different disclosure regimes requires a granular, operational focus. It moves beyond theoretical comparison to the precise mechanics of compliance and strategic action. For a multinational corporation, this means establishing a robust internal framework for document preservation, collection, and production that is flexible enough to adapt to the demands of any jurisdiction. The execution phase is where strategic plans are translated into defensible actions that can withstand judicial scrutiny.

The Operational Playbook for Cross Border Discovery

When litigation is anticipated, a company must immediately implement a “litigation hold” to preserve all potentially relevant documents. The execution of this hold varies significantly depending on the jurisdictions involved. The following steps outline a basic operational playbook for a company facing a dispute with potential exposure in both the U.S. and England.

- Immediate Preservation Notice ▴ Upon reasonable anticipation of litigation, the legal department must issue a formal litigation hold notice to all relevant employees (“custodians”). Under the English CPR, this duty extends to notifying former employees and taking reasonable steps to ensure third-party agents preserve relevant documents. This is a broader initial duty than typically required in the U.S.

- Identify the “Data Universe” ▴ The company must identify all sources of potentially relevant information. This includes emails, server data, laptops, mobile devices, and cloud storage. The English PD57AD explicitly requires parties to understand their “data universe” at a very early stage.

- Custodian Interviews ▴ The legal team should interview key custodians to understand how they create, store, and manage documents. This is critical for ensuring the litigation hold is effective and for planning the collection process.

- Data Collection and Processing ▴ Data must be collected in a forensically sound manner. This is typically handled by an e-discovery vendor. The data is then processed to remove duplicate documents and prepare it for attorney review.

- Document Review ▴ Attorneys review the collected documents to determine their relevance to the case and to identify any privileged material. This is the most expensive phase of discovery. The use of Technology Assisted Review (TAR) or AI software is increasingly common to manage costs, a practice encouraged by the English courts.

- Production ▴ Relevant, non-privileged documents are produced to the opposing party in a format agreed upon by the parties or ordered by the court.

Quantitative Modeling of Discovery Costs

The strategic decision to litigate in one jurisdiction over another is heavily influenced by cost. The following table provides a hypothetical cost model for a medium-sized commercial dispute, illustrating the dramatic difference in discovery expenses between the U.S. and English systems. The model assumes a dataset of 500 gigabytes of raw data.

| Discovery Phase | U.S. System (Broad Discovery) – Estimated Cost | English System (Managed Disclosure) – Estimated Cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Processing & Hosting | $75,000 | $50,000 | Assumes a narrower scope of collection under the English system reduces the volume of data hosted. |

| Attorney Document Review | $1,200,000 | $400,000 | Assumes a review rate of 50 documents per hour at $400/hour. The broader U.S. relevance standard leads to a much larger review set. |

| Depositions | $250,000 | $0 | Includes costs for preparing for and taking/defending 10 depositions. This process does not exist in the English system. |

| Discovery Motions & Disputes | $150,000 | $75,000 | The cooperative framework of PD57AD generally leads to fewer disputes over the scope of disclosure. |

| e-Discovery Vendor & Project Management | $100,000 | $60,000 | Costs are proportional to the volume of data and complexity of the project. |

| Total Estimated Cost | $1,775,000 | $585,000 | Illustrates how the procedural rules directly translate into a significant cost differential. |

Predictive Scenario Analysis a Patent Dispute

Imagine a German automotive technology firm, “AutoTech,” which holds patents for a new type of battery sensor. A U.S.-based competitor, “Global Motors,” launches a new electric vehicle that AutoTech believes infringes on its patents. Global Motors has its research and development headquarters in California, its European sales office in London, and its manufacturing plant in Munich.

AutoTech’s legal team must decide where to initiate litigation. Filing in the U.S. offers access to the broad discovery tools of the FRCP. AutoTech could depose Global Motors’ engineers, demand internal emails discussing the new vehicle’s design, and request all documents related to their R&D process. This would be a powerful tool to prove infringement, even without a “smoking gun” document at the outset.

The downside is the immense cost, estimated to be several million dollars, and the risk that Global Motors will use the same tools to launch a burdensome counter-assault on AutoTech’s own files. The German parent company’s documents could also be drawn into the U.S. discovery process.

Filing in England presents a different strategic calculation. The disclosure process would be more constrained. AutoTech would need to work with Global Motors to agree on the specific technical issues in dispute and then request targeted categories of documents related to those issues. This would be far less expensive.

The “loser pays” rule means that if AutoTech is confident in its case, it could recover a large portion of its legal fees from Global Motors. The lack of depositions is a drawback, as they would lose the opportunity to question key engineers under oath before trial.

Litigation in the UK is underpinned by the presumption that costs follow the event; this means that the loser pays the winner’s legal costs.

Filing in Germany, a civil law jurisdiction, would be the most restrictive. There would be no pre-trial discovery in the Anglo-American sense. AutoTech would have to present its case based almost entirely on the evidence it already possesses, such as its own analysis of the Global Motors vehicle. The process would be faster and much cheaper, but the burden of proof would rest almost entirely on AutoTech’s own investigative work.

The German court would lead the process, and the judges might appoint their own expert to evaluate the technology. The strategy here is one of speed and efficiency, banking on a strong, self-contained case.

Ultimately, AutoTech’s decision depends on its strategic priorities. If its primary goal is to uncover evidence it believes exists within Global Motors’ files, the U.S. is the logical choice, despite the cost. If its priority is a cost-effective resolution and it has a strong case, England is an attractive option.

If speed and efficiency are paramount and its evidence is already solid, Germany may be the best venue. This scenario demonstrates how jurisdictional differences in disclosure rules are not mere procedural details; they are the central pillars upon which the entire litigation strategy is built.

How Do Blocking Statutes Affect This Scenario?

If Global Motors’ manufacturing plant in Munich holds key documents, German privacy and data protection laws could act as blocking statutes. Even in a U.S. or UK lawsuit, Global Motors could argue that it is prohibited by German law from producing certain employee data or technical specifications stored in Germany. This would force AutoTech to engage in a complex legal battle over international comity, potentially delaying the case and requiring them to seek evidence through more formal and time-consuming government-to-government channels. The litigation strategy must account for this layer of complexity from the very beginning.

- Initial Assessment ▴ The first step is to identify any foreign laws that could impede the discovery process. This includes data privacy laws, state secrecy acts, and specific blocking statutes.

- Comity Analysis ▴ Courts in the U.S. will typically conduct a multi-factor comity analysis to determine whether to compel production despite a foreign law. Parties must be prepared to argue these factors, which include the interests of each nation and the hardship of compliance.

- Alternative Methods ▴ A proactive strategy involves identifying alternative means of obtaining the information, such as through the Hague Evidence Convention or other mutual legal assistance treaties.

References

- Clayton Utz. “Litigation 101 ▴ Discovery ▴ Understanding the process and obligations.” 9 June 2022.

- Society for Computers & Law. “Disclosure ▴ Three Jurisdictions ▴ Three Approaches.” 20 December 2011.

- Penningtons Manches Cooper. “Transatlantic litigation – disclosure, discovery and the difference.” 8 August 2024.

- Strong, S.I. “Jurisdictional Discovery in United States Federal Courts.” Washington and Lee Law Review, vol. 68, no. 3, 2011.

- Baker Botts. “Between a Legal Rock and a Hard Place ▴ Balancing Foreign Law and U.S. Discovery Obligations.” 1 July 2024.

Reflection

The analysis of jurisdictional disclosure rules reveals a critical truth about modern litigation ▴ the procedural framework is the strategic battlefield. Mastery of these systems provides a decisive operational edge. The rules governing the flow of information are not neutral; they are imbued with the legal and economic philosophies of their jurisdictions. Viewing these regimes as distinct operating systems, each with its own protocols, command structures, and vulnerabilities, allows a litigant to move beyond reactive compliance.

It enables the design of a proactive strategy that leverages the inherent architecture of the chosen forum. The ultimate objective is to construct a litigation framework that aligns the procedural environment with the substantive strengths of your case, transforming procedural requirements into strategic assets.

How Does Your Internal Framework Measure Up?

Consider your own organization’s readiness to engage in a multi-jurisdictional dispute. Is your data architecture designed to facilitate a targeted, efficient, and defensible document preservation and collection process? Can you effectively model the cost-benefit analysis of litigating in New York versus London or Frankfurt? The insights gained from understanding these systems are components of a larger intelligence apparatus.

True strategic capability is achieved when this legal systems analysis is integrated with your firm’s technological infrastructure and its overarching risk management philosophy. The question becomes how to architect an internal system that is as sophisticated and adaptable as the external legal systems it must navigate.

Glossary

Litigation Strategy

Disclosure Rules

Civil Law

Civil Procedure Rules

English System

Discovery Process

Blocking Statutes

Document Preservation

E-Discovery

Global Motors

Jurisdictional Differences