Concept

The determination of a Central Counterparty’s (CCP) minimum required skin-in-the-game is an exercise in system architecture, an act of calibrating the core incentive structure of modern financial markets. Viewing this regulatory requirement as a simple capital buffer is a fundamental misinterpretation of its function. Its true purpose is to serve as the primary alignment mechanism between the CCP’s commercial objectives and its public utility function of maintaining market stability. The precise quantum of capital a CCP must place at risk is the subject of intense analytical debate because it directly governs the clearinghouse’s own risk appetite.

When a CCP designs its margin models, stress tests, and member acceptance criteria, the knowledge that its own capital is the first institutional tranche to be consumed after a defaulter’s resources are exhausted provides a powerful and necessary constraint on its behavior. The entire system of central clearing is predicated on the principle of ‘defaulter pays’. A member’s failure should be absorbed by their own posted collateral and default fund contributions. The CCP’s skin-in-the-game is the critical backstop that precedes the socialization of losses among the surviving, non-defaulting members. Therefore, its calibration is a direct reflection of a regulator’s philosophy on systemic risk mitigation.

A regulator’s task is to architect a system where the CCP’s incentives are perfectly aligned with those of the clearing members and the market as a whole. This alignment is achieved by ensuring the CCP’s own contribution is substantial enough to make it a vigilant and impartial risk manager. An insufficient contribution risks moral hazard; the CCP might be tempted to lower standards to attract more clearing business, knowing that the financial consequences of a major default would be borne almost entirely by its members. Conversely, an excessively large requirement could render the CCP model uneconomical, increasing the cost of clearing for all participants and potentially driving risk back into less transparent, bilateral markets.

The regulatory process, therefore, involves a sophisticated analysis of the CCP’s entire risk management framework. It scrutinizes the margin models that determine the first line of defense, the stress testing scenarios that size the default fund, and the operational integrity of the default management process. The skin-in-the-game is the fulcrum upon which this entire structure balances. It is the component that ensures the CCP operates not merely as a transaction processor, but as a disciplined guardian of market integrity, with a direct, tangible, and painful financial stake in the outcome of its own risk management decisions.

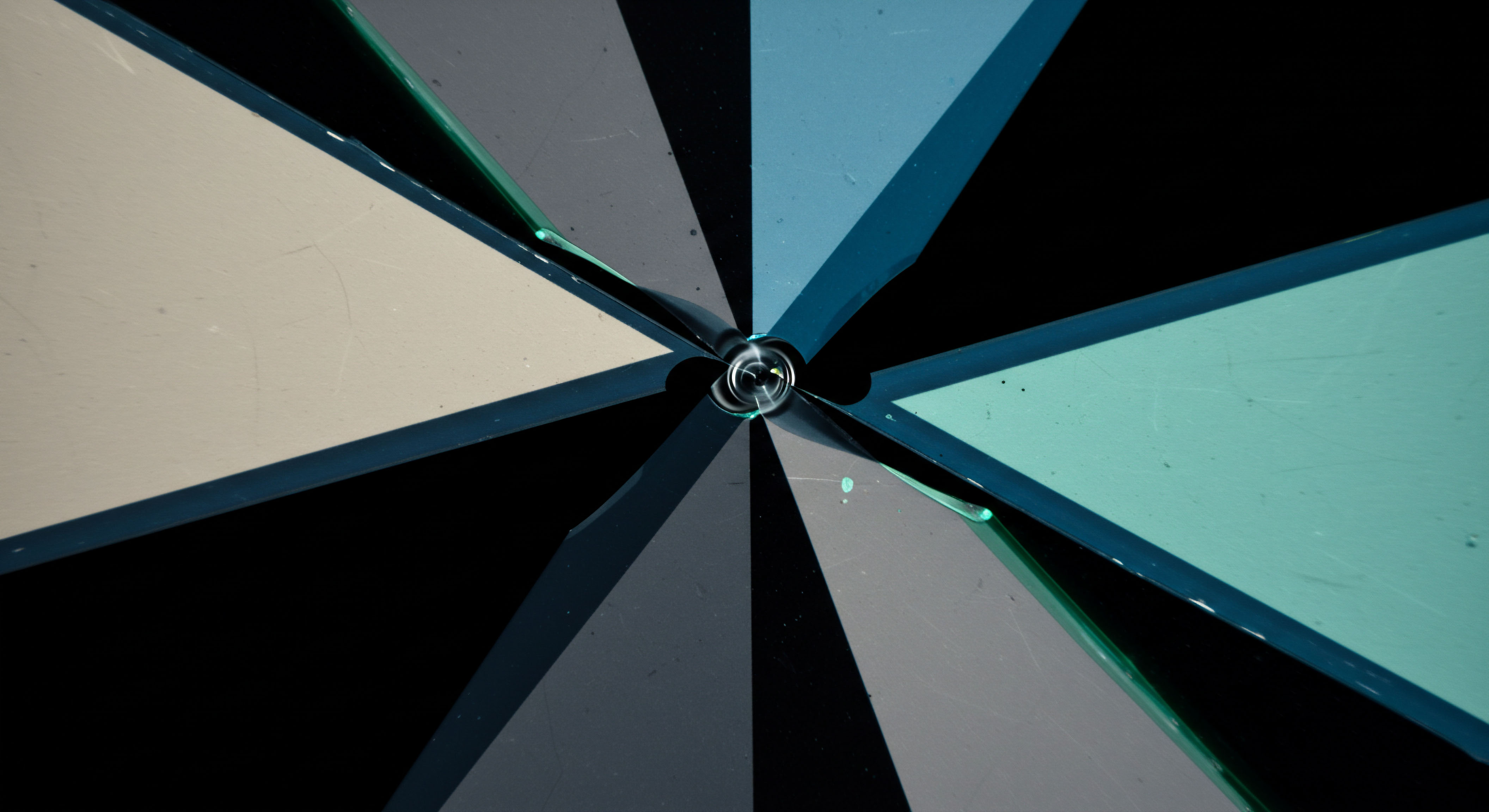

A CCP’s skin-in-the-game is the calibrated incentive mechanism ensuring its private interests align with its public duty to maintain financial stability.

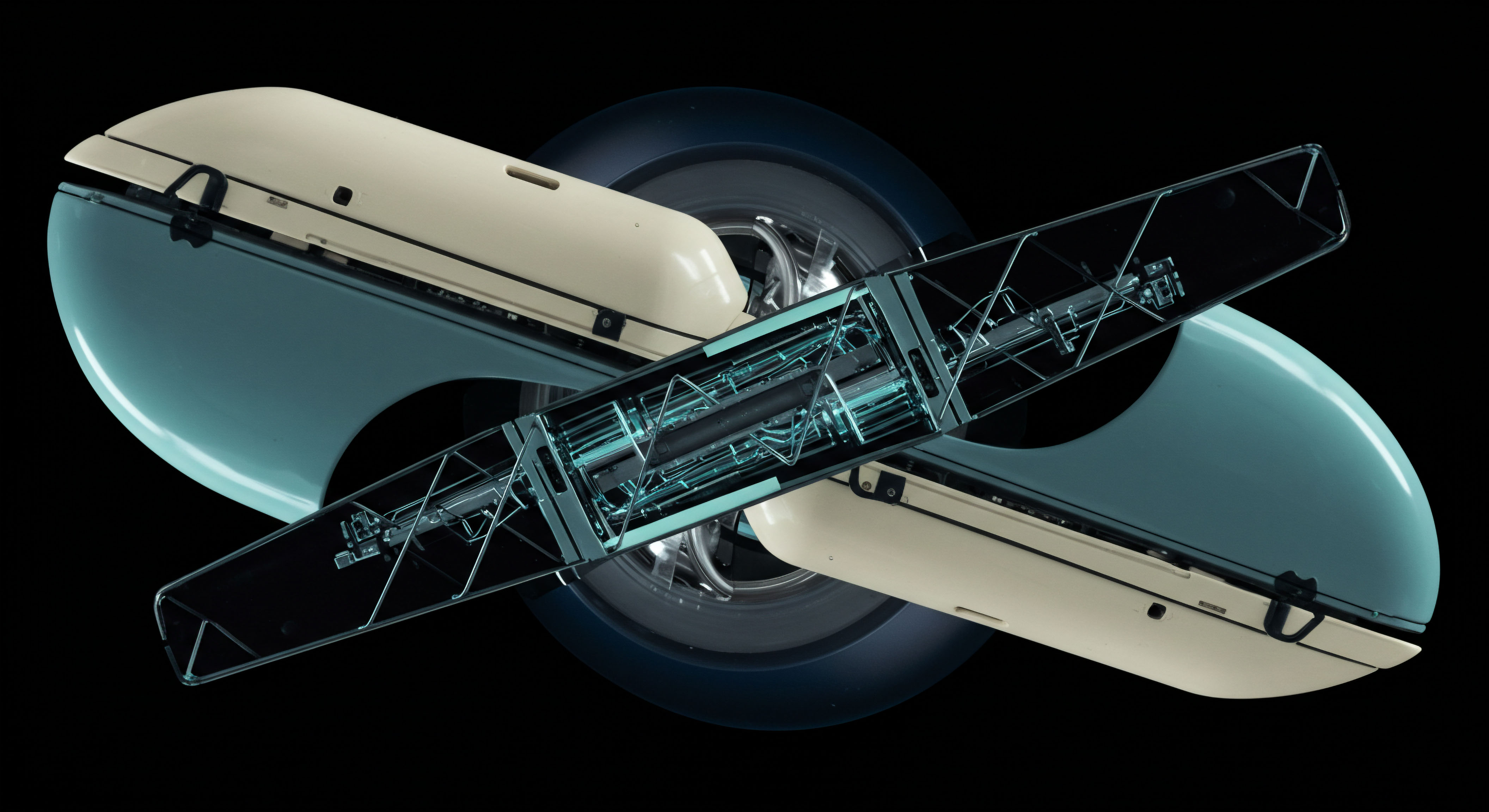

Understanding this concept from a systems perspective reveals its elegance. The CCP sits at the nexus of a complex network of exposures. Each member represents a node of potential risk. The CCP’s role is to manage the net risk of this entire system.

The regulatory determination of its own capital at risk is the primary input that governs the parameters of this management function. It is a quantitative expression of the principle that the entity best placed to control the risk must also have a meaningful exposure to that risk. The debate over its size, whether it should be a percentage of regulatory capital or a function of the total default fund size, is a debate about the sensitivity of this control mechanism. A small amount provides a signal, while a larger, more material amount provides a powerful forcing function, compelling the CCP to invest in superior risk analytics, enforce stringent membership criteria, and act decisively during a crisis. The process is a continuous loop of surveillance and adjustment, where regulators observe market volatility, the performance of CCPs under stress, and the evolving nature of financial products to ensure this critical component of the market’s operating system is calibrated for resilience.

Strategy

The regulatory strategy for calibrating a CCP’s skin-in-the-game (SITG) is rooted in a multi-layered defense model, commonly known as the default waterfall. This structure is a predefined sequence for allocating losses from a member default, and the CCP’s SITG is a strategically positioned layer within it. The overarching goal is to create a resilient system that can absorb extreme shocks while maintaining proper incentives for all participants.

Regulators must balance two primary objectives ▴ ensuring the CCP is a prudent risk manager and avoiding the imposition of uneconomic costs on the clearing system. This leads to distinct strategic approaches, primarily differentiated by their degree of prescriptiveness versus reliance on high-level principles.

The Architecture of the Default Waterfall

A CCP’s default waterfall is the operational sequence for loss allocation. Understanding the strategic placement of SITG requires understanding the layers that precede and follow it. The design is a clear application of the ‘defaulter pays’ principle, escalating from individual responsibility to mutualized liability.

- Defaulter’s Resources This is the first and most critical layer. It comprises all the financial resources posted by the defaulting clearing member.

- Initial Margin ▴ Collateral collected to cover potential future exposure from a member’s positions, typically calculated to a high confidence level (e.g. 99% or 99.5%) over a specified close-out period.

- Variation Margin ▴ Realized profits and losses on a member’s portfolio, collected or paid out daily to prevent the accumulation of large exposures.

- Default Fund Contribution ▴ The defaulting member’s own contribution to a separate, mutualized fund designed to absorb losses exceeding its initial margin.

- CCP’s Skin-In-The-Game This is the second layer of the waterfall. It consists of a dedicated portion of the CCP’s own capital. Its strategic placement, immediately after the defaulter’s resources are exhausted, is what creates the powerful incentive for the CCP. The CCP suffers a direct financial loss before any non-defaulting member’s contribution to the default fund is touched.

- Surviving Members’ Default Fund Contributions This is the third layer, representing the mutualization of risk. If the defaulter’s resources and the CCP’s SITG are insufficient to cover the losses, the collective contributions of the non-defaulting clearing members to the default fund are used.

- Further Loss Allocation Tools The final layers are reserved for extreme, often un-survivable, events. These are recovery and resolution tools which may include rights to call for additional default fund contributions from surviving members (cash calls) or mechanisms to allocate losses among them (e.g. variation margin gains haircutting).

Comparative Regulatory Philosophies

Regulators globally adhere to the same high-level principles established by bodies like the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (CPMI-IOSCO). However, the implementation of these principles reveals different strategic philosophies. The primary divergence is between a prescriptive, rules-based approach and a more flexible, principles-based framework.

The European approach, codified in the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR), is highly prescriptive. It explicitly defines the quantum and position of SITG. This strategy prioritizes harmonization and legal certainty. By setting a clear, non-negotiable floor, it ensures a baseline level of incentive alignment across all EU-based CCPs.

The US framework, by contrast, historically has been more principles-based, focusing on the adequacy of the CCP’s total financial resources to meet a “Cover 2” standard (i.e. withstand the default of its two largest members) without mandating a specific SITG amount or position. This approach allows for greater flexibility, enabling a CCP to tailor its capital structure to its specific risk profile, but relies more heavily on supervisory judgment to ensure incentives are properly aligned.

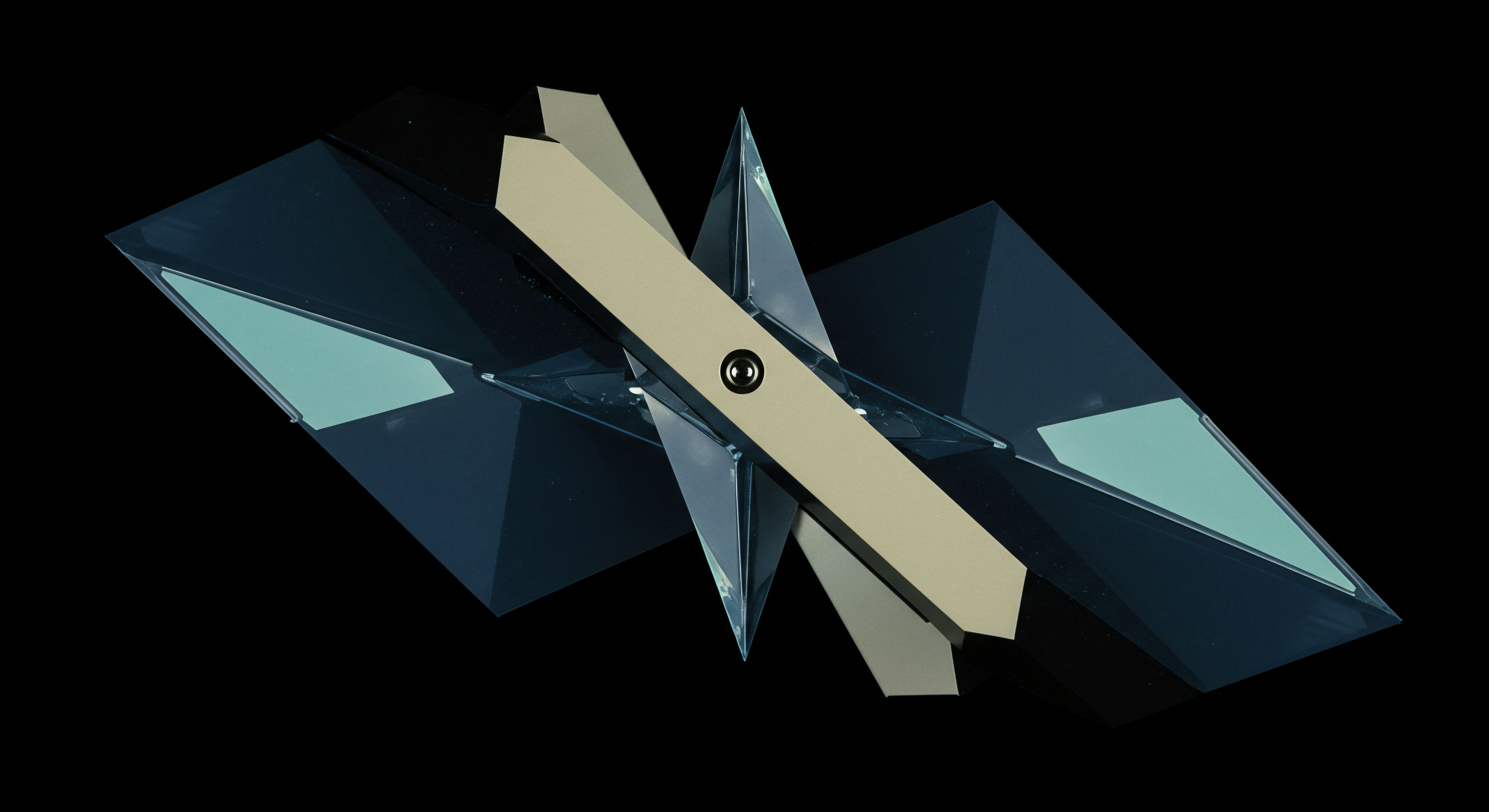

Regulatory strategies for CCP skin-in-the-game diverge between prescriptive rules that ensure uniformity and principles-based frameworks that allow for tailored risk management.

The table below compares these two strategic approaches, highlighting the architectural trade-offs inherent in each regulatory design.

| Attribute | Prescriptive (EU/EMIR Model) | Principles-Based (Traditional US Model) |

|---|---|---|

| SITG Sizing | Defined by a specific formula. For example, at least 25% of the CCP’s minimum regulatory capital requirement. | No explicit minimum SITG amount. Focus is on the adequacy of total financial resources to meet a specific stress scenario (e.g. Cover 2). |

| Waterfall Position | Mandated position. SITG must be used after the defaulter’s resources and before the non-defaulting members’ default fund contributions. | Positioning can be more flexible. The focus is on the result (resilience) rather than the specific sequence, though market practice often follows a similar structure. |

| Primary Advantage | Provides legal certainty, consistency, and a clear, harmonized standard across all regulated entities. Prevents a “race to the bottom” on capital standards. | Allows for greater flexibility for the CCP to optimize its capital structure and risk management framework based on the specific products it clears and the risks it faces. |

| Primary Disadvantage | Can be a one-size-fits-all approach. The fixed percentage may not be optimally calibrated for all CCPs, potentially being too low for some and too high for others. | Creates a greater reliance on supervisory judgment to assess the adequacy of incentives. Can lead to inconsistencies in application across different CCPs and supervisors. |

| Incentive Mechanism | The incentive is direct and explicit. The CCP knows precisely the amount of its capital at risk and its position in the loss hierarchy. | The incentive is implicit. The CCP is incentivized to manage risk prudently to avoid triggering a failure scenario that would consume its capital and lead to reputational ruin. |

The Evolving Strategy Second Skin

Recent regulatory developments, particularly in the European Union with the CCP Recovery and Resolution Regulation (CCPRRR), have introduced a further strategic layer a “second skin-in-the-game” (SSITG). This is an additional amount of the CCP’s own pre-funded resources that must be used after the mutualized default fund is depleted but before the CCP can trigger more extreme recovery tools, like cash calls on surviving members. The strategic purpose of this second tranche is to strengthen the CCP’s incentive to manage the entire default process effectively.

It ensures the CCP has a financial stake not just in preventing defaults, but also in containing the fallout from a default and minimizing the impact on the surviving members even after the initial SITG and the default fund have been consumed. This evolution shows a clear regulatory direction of travel ▴ continually refining the incentive structure to ensure the CCP’s interests are aligned with the market’s throughout the entire lifecycle of a crisis, from prevention to recovery.

Execution

The execution of regulatory policy on CCP skin-in-the-game translates strategic principles into a set of quantitative and procedural requirements. Regulators do not simply pick a number; they employ a detailed methodology that scrutinizes the CCP’s entire risk management architecture. This involves a granular assessment of the components of the CCP’s capital, the models used for stress testing, and the precise calculation of the SITG contribution. For an institutional market participant, understanding this execution layer is critical for evaluating the robustness of a CCP and the true level of risk in the system.

How Do Regulators Quantify Required Capital?

The foundation for determining SITG is the CCP’s overall regulatory capital requirement. This capital is intended to cover a range of risks beyond member defaults. Under a framework like EMIR, the total capital is built up from several components, ensuring the CCP can conduct an orderly wind-down or restructuring and cover various operational and business risks even without a member default. The SITG is then calculated as a percentage of this total required capital.

The primary components of a CCP’s regulatory capital include:

- Capital for wind-down or restructuring ▴ An amount sufficient to ensure the CCP can cease its operations in an orderly manner without causing a market disruption. This includes costs for maintaining operations for a period, closing out contracts, and returning member assets.

- Capital for operational and legal risks ▴ Resources to cover losses that could arise from inadequate internal processes, people, and systems, or from external events (e.g. cyber-attacks, legal challenges). This quantification is often based on advanced measurement approaches that model the frequency and severity of potential operational loss events.

- Capital for credit, counterparty, and market risks ▴ This covers risks not already accounted for by margin and default fund contributions. It includes investment risk on the CCP’s own liquid assets and exposures to its service providers.

- Capital for business risk ▴ A buffer to absorb losses from adverse changes in the CCP’s business environment, such as a decline in revenue or an increase in operating costs, ensuring it can remain a going concern.

The sum of these components forms the CCP’s minimum regulatory capital. The SITG is then typically set as a floor percentage of this amount. For instance, EMIR stipulates that the CCP must contribute at least 25% of its minimum regulatory capital to the default waterfall as its first tranche of skin-in-the-game. This ensures the SITG is proportional to the overall scale and risk profile of the CCP.

The Quantitative Modeling of the Default Waterfall

The core of the execution process lies in the quantitative modeling of the default waterfall. Regulators require CCPs to conduct rigorous stress testing to ensure their total pre-funded resources (initial margin and default fund) are sufficient to withstand extreme but plausible market scenarios. The internationally agreed upon standard is “Cover 2,” which requires a CCP to demonstrate that it has sufficient resources to survive the default of its two largest clearing members (and their affiliates) under such stressed conditions. The sizing of the SITG is intrinsically linked to this process, as it represents the CCP’s own contribution to this defensive wall.

Let’s consider a hypothetical, simplified example to illustrate the mechanics. A regulator is assessing a CCP’s compliance.

- Stress Scenario Definition ▴ The CCP, under regulatory supervision, defines a set of extreme but plausible market scenarios. These could include sharp, unexpected price moves, liquidity freezes in certain asset classes, or sovereign credit events.

- Exposure Calculation ▴ The CCP calculates the potential losses it would face from each clearing member’s portfolio under each stress scenario. The two members creating the largest aggregate losses are identified as “Cover 2.” Let’s assume these losses, after liquidating the defaulters’ initial margin, are $1.8 billion.

- Default Fund Sizing ▴ The total size of the mutualized default fund must be sufficient to cover this $1.8 billion stress loss. The CCP collects contributions from all its members to build this fund. Let’s assume the total default fund is sized at $2.0 billion.

- SITG Calculation ▴ Now, the regulator verifies the CCP’s SITG contribution. Suppose the CCP’s minimum regulatory capital, calculated based on its operational, business, and other risks, is $400 million. Under the EMIR framework, the CCP’s required SITG would be 25% of this amount, which is $100 million.

This SITG of $100 million is placed in the waterfall after the defaulters’ own resources but before the surviving members’ $2.0 billion default fund. While it may seem small relative to the total default fund, its strategic importance is paramount. It ensures the CCP loses a significant amount of its own capital before the mutualized fund is ever touched, creating a powerful incentive for prudent risk management.

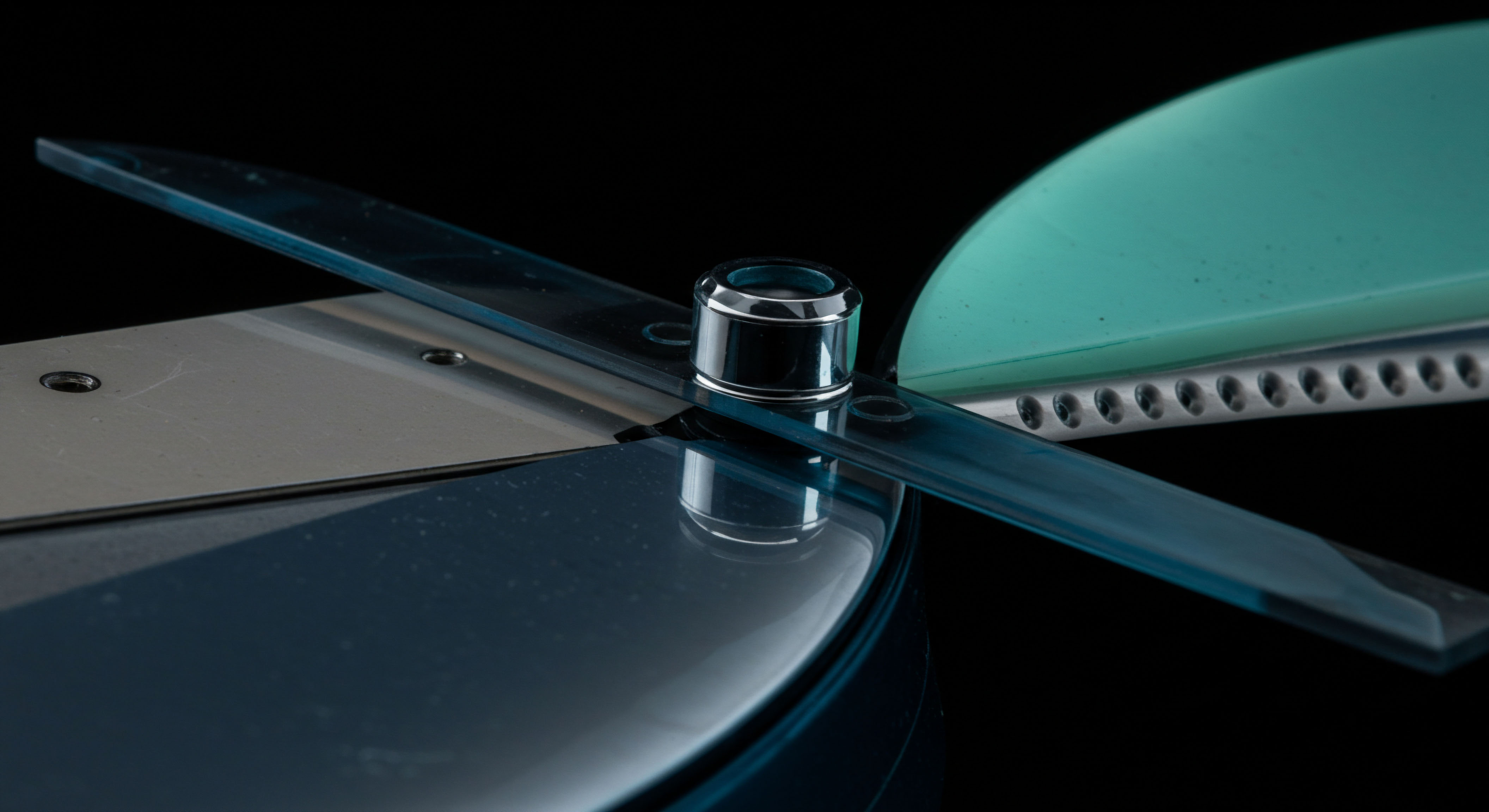

The execution of SITG policy hinges on rigorous stress testing and a clear, quantitative link between the CCP’s overall regulatory capital and its contribution to the default waterfall.

What Is the Practical Impact of Different Sizing Methodologies?

The debate around SITG sizing is not merely academic; different methodologies can produce vastly different results and incentive structures. The prescriptive regulatory approach (e.g. 25% of capital) provides a clear floor. However, some academic research proposes alternative methodologies that link SITG to the size of the mutualized risk.

For example, a model might suggest that SITG should be 15-20% of the total default fund to create adequate incentives. This alternative approach would link the CCP’s risk directly to the amount of risk its members are underwriting.

The following table demonstrates the potential difference in outcomes between these two execution methodologies, using our previous example.

| Calculation Metric | Regulatory Mandate (EMIR) | Academic Incentive Model |

|---|---|---|

| Basis for Calculation | Minimum Regulatory Capital | Total Default Fund Size |

| Hypothetical Input Value | $400 million | $2.0 billion |

| Applied Percentage | 25% | 15% |

| Resulting SITG Amount | $100 million | $300 million |

| Primary Incentive Focus | Ensures SITG is proportional to the CCP’s overall operational and business risk profile. Provides a stable and predictable minimum. | Directly links the CCP’s financial stake to the amount of mutualized risk it is managing on behalf of its members. Creates a stronger sensitivity to changes in market-wide risk. |

As the table illustrates, the execution methodology has a profound impact. The academic model, by tying SITG to the scale of potential member losses, would require a significantly larger capital contribution from the CCP in this scenario. Regulators must weigh the benefits of the stronger incentive created by such a model against the potential costs of imposing higher capital requirements on CCPs. This is a core tension in the execution of regulatory policy ▴ calibrating the system for maximum safety without stifling the market it is designed to protect.

How Is Ongoing Compliance Ensured?

The determination of SITG is not a one-time event. It is a dynamic process of continuous supervision. Regulators require CCPs to:

- Conduct daily stress tests ▴ To ensure that the “Cover 2” standard is met on a daily basis as market positions and volatility change.

- Perform regular model validation ▴ An independent team must validate the models used for margin calculation and stress testing to ensure they are performing as expected and are not becoming outdated.

- Undergo periodic supervisory reviews ▴ Regulators conduct deep-dive reviews of the CCP’s risk management framework, including its capital calculations and SITG adequacy, on a regular basis.

- Adhere to disclosure requirements ▴ CCPs must publicly disclose key information about their risk management framework and the size and composition of their default waterfall, allowing market participants to conduct their own due diligence.

This continuous oversight loop ensures that the execution of the SITG policy remains effective as market conditions evolve, providing a resilient and adaptive core to the financial system’s architecture.

References

- Cont, Rama, and Samim Ghamami. “Skin in the Game ▴ Risk Analysis of Central Counterparties.” 2023.

- Berndsen, Ron. “A CCP’s skin-in-the-game ▴ Is there a trade-off?” The World Federation of Exchanges, Oct. 2020.

- European Association of CCP Clearing Houses (EACH). “EACH Paper ▴ Carrots and sticks ▴ How the skin in the game incentivises CCPs to perform robust risk management.” 2017.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. “Skin in the Game ▴ Central Counterparty Risk Controls and Incentives.” Bulletin, June 2015.

- European Securities and Markets Authority. “Final Report ▴ RTS on the methodology for calculation and maintenance of the additional amount of pre-funded dedicated own resources.” 31 Jan. 2022.

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and International Organization of Securities Commissions. “Principles for financial market infrastructures.” April 2012.

- Murphy, David. “Stress Testing and Bank-Capital Regulation ▴ A Survey.” Financial Management, vol. 46, no. 1, 2017, pp. 195-220.

- Duffie, Darrell, and Haoxiang Zhu. “Does a Central Clearing Counterparty Reduce Counterparty Risk?” The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2011, pp. 74-95.

Reflection

The regulatory architecture governing a CCP’s skin-in-the-game is a testament to the systemic function of incentives. Having examined the concept, strategy, and execution, the critical question for any institutional participant shifts from “what is the rule?” to “how does this specific calibration affect my own risk calculus?” The choice of a CCP is a choice of a risk management partner, and its skin-in-the-game is the most direct statement of its commitment to that partnership. Does your own operational framework fully account for the differences in these regulatory philosophies? How does the specific SITG quantum and waterfall position of your chosen CCP influence your own internal stress tests and capital allocation decisions?

The knowledge gained here is a component of a larger system of institutional intelligence. A superior operational edge is achieved when this external regulatory architecture is integrated into your own internal framework, transforming compliance from a passive requirement into an active source of strategic advantage.

Glossary

Central Counterparty

Skin-In-The-Game

Default Fund Contributions

Systemic Risk Mitigation

Clearing Members

Risk Management Framework

Risk Management

Regulatory Capital

Total Default

Default Waterfall

Initial Margin

Default Fund Contribution

Default Fund

Surviving Members

Recovery and Resolution

Cpmi-Iosco

European Market Infrastructure Regulation

Incentive Alignment

Risk Profile

Ccp Recovery and Resolution

Mutualized Default Fund

Stress Testing

Minimum Regulatory Capital

Minimum Regulatory