Concept

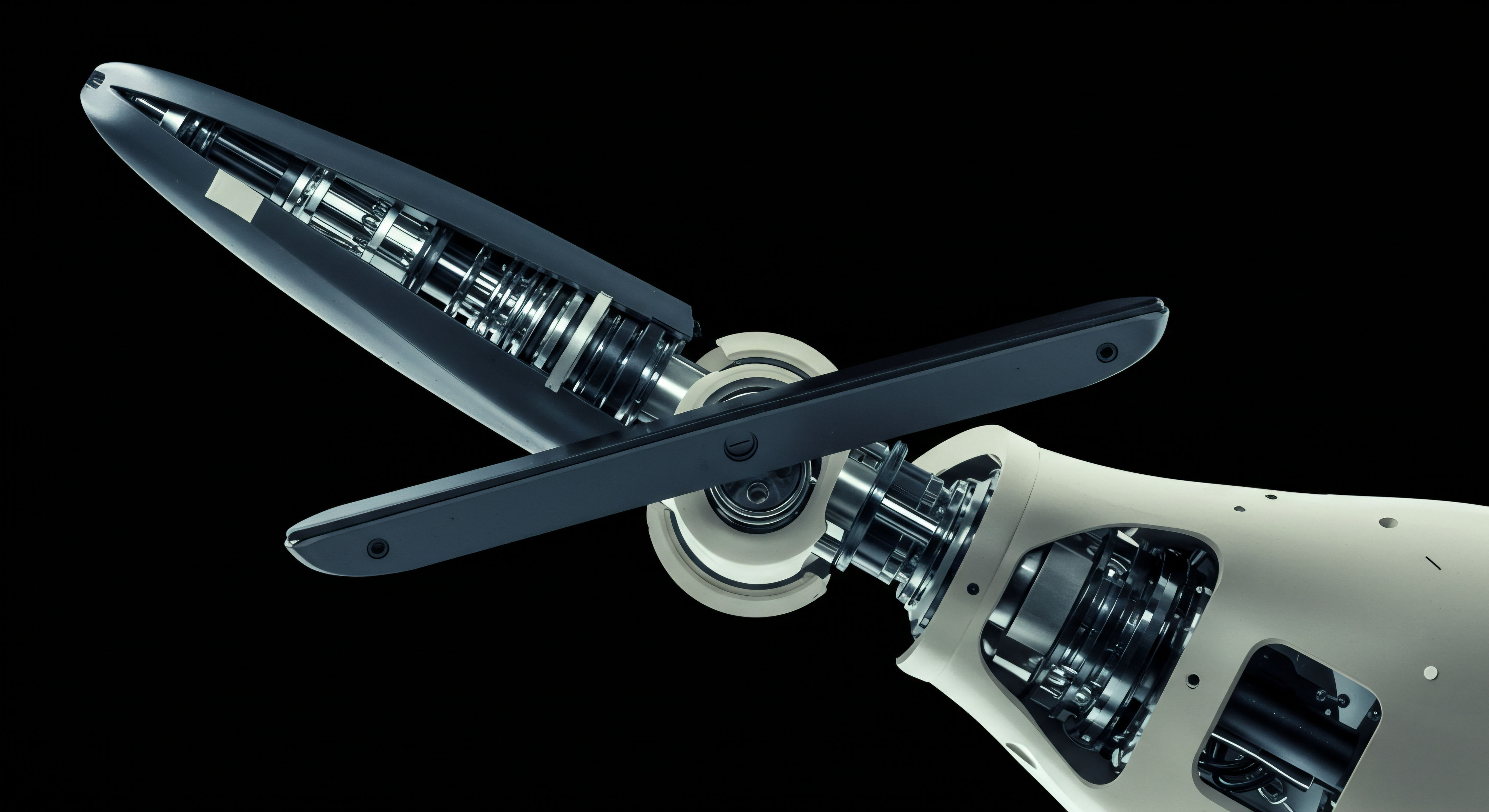

The architecture of any robust financial system is defined by its control mechanisms, the pre-programmed responses to stress that dictate survival. Within the intricate network of bilateral credit agreements, the cross-default threshold amount represents a critical, and often misunderstood, systemic circuit breaker. Its function is direct and absolute. This single, negotiated value determines the precise point at which financial distress in one part of a counterparty’s portfolio creates a default event across all their obligations with your firm.

It is the codified line between contained financial difficulty and contagious default. Understanding its direct impact on counterparty risk exposure requires viewing it not as a legal formality, but as the primary calibration tool for a firm’s sensitivity to external financial contagion.

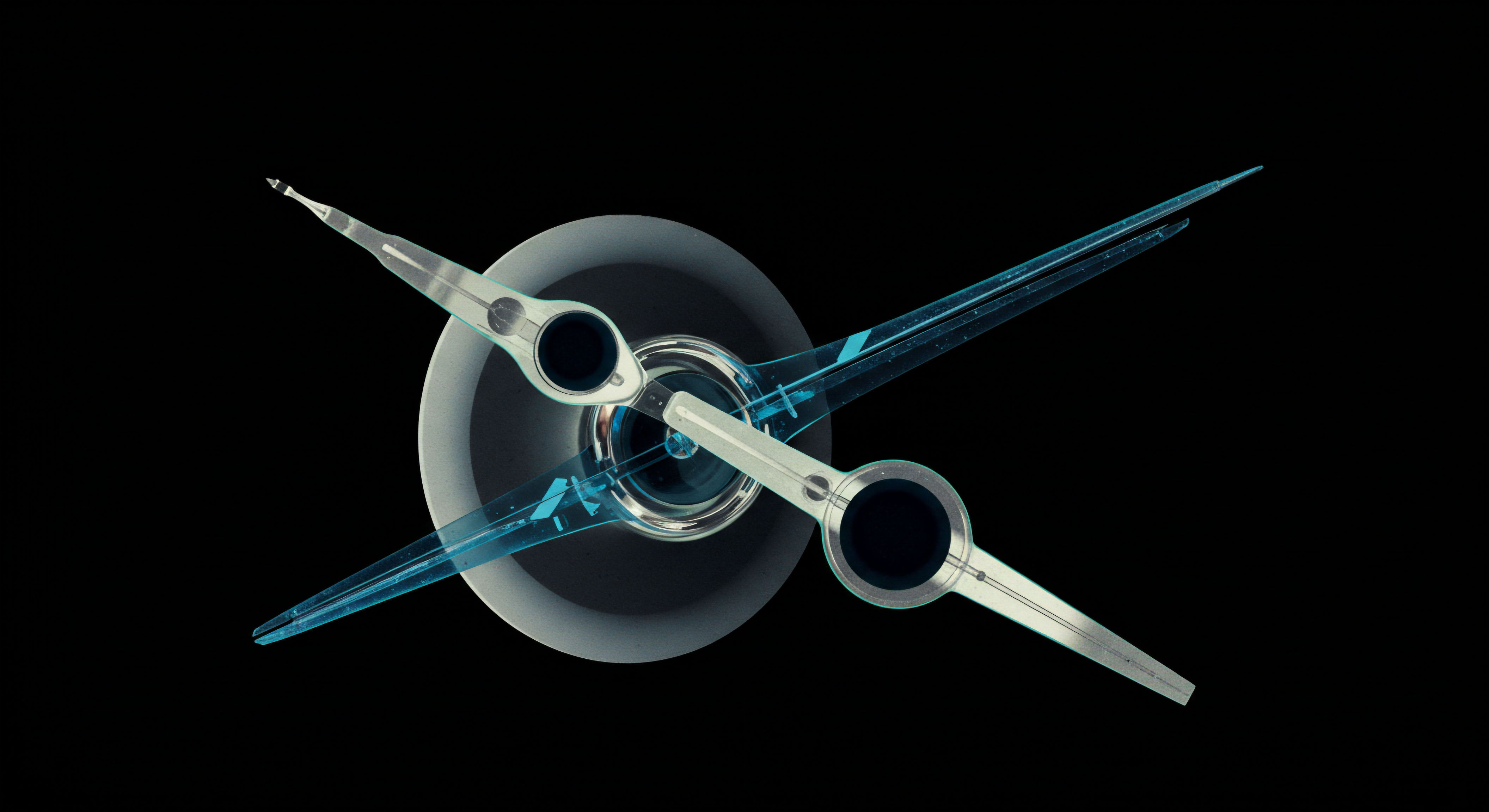

A firm’s exposure to a counterparty is rarely limited to a single transaction. It is a web of trades, loans, and other financial instruments, each with its own terms. A cross-default clause links these disparate agreements. It stipulates that a default on a specified external debt obligation ▴ known as “Specified Indebtedness” ▴ is considered a default on the agreement you hold with them.

The threshold amount is the monetary value that this external default must exceed to activate the clause. A threshold set at $20 million means your counterparty can default on other loans up to that amount without triggering any consequence in your agreement. The moment a default on other obligations surpasses $20 million, your firm gains the immediate right to terminate all transactions and seize collateral.

The cross-default threshold transforms a counterparty’s external financial stability into a direct and measurable component of your own firm’s risk framework.

This mechanism fundamentally alters the nature of counterparty risk. The risk is no longer confined to the specific performance of the transactions you have with a counterparty. It expands to encompass the entirety of their financial stability and discipline across all their credit relationships. The threshold amount is the lens through which you view that external risk.

A low threshold provides a highly sensitive early warning system, signaling potential distress at the first sign of trouble. Conversely, a high threshold is designed to filter out minor financial noise, ensuring that only genuinely systemic threats to the counterparty’s solvency can trigger a default event. The choice between these settings is a foundational decision in the architecture of a firm’s risk management protocol, directly shaping its resilience to market-wide credit events.

What Defines the Thresholds Scope?

The operational power of the threshold is defined by the scope of “Specified Indebtedness” within the credit support annex (CSA) or ISDA Master Agreement. This definition dictates which types of a counterparty’s debt are monitored. A narrowly defined scope might only include public bonds and syndicated loans, offering a clear but limited view of their financial health.

A broader definition could encompass obligations under other derivative transactions, private credit lines, and other forms of borrowing. This wider net provides a more holistic picture of counterparty leverage and potential stress points.

The calibration of the threshold amount itself is an expression of risk tolerance. For a major global bank, this is typically set as a percentage of its total shareholders’ equity, such as 2% or 3%. This ensures the threshold scales with the institution’s size and represents a truly material threat to its solvency. For smaller entities or funds, a fixed dollar amount is more common.

The negotiation of this figure is a critical part of the counterparty onboarding process, reflecting a deep analysis of the counterparty’s balance sheet, their other credit relationships, and the overall volatility of the markets in which they operate. A firm must model how a potential breach would occur and ensure the threshold provides enough time to act before the counterparty’s position deteriorates irretrievably.

Strategy

Strategically, the cross-default threshold is a tool for managing the informational asymmetry inherent in credit relationships. A firm cannot perfectly monitor all of a counterparty’s activities. The threshold serves as a proxy, a pre-agreed signal that automatically communicates a significant negative credit event. The strategy behind setting this threshold involves a careful balance between protection and stability.

An overly aggressive, low threshold can create relationship fragility, while a passive, high threshold can expose the firm to unacceptable losses. The optimal strategy is one that aligns the threshold’s sensitivity with the firm’s specific risk appetite and the nature of its relationship with the counterparty.

Calibrating the Threshold a Strategic Balancing Act

The decision of where to set the cross-default threshold is a fundamental strategic choice with significant consequences for both risk management and commercial relationships. It is a process of calibrating a firm’s defenses to the specific level of threat it is willing to tolerate from each counterparty.

- The Low Threshold Strategy This approach prioritizes maximum protection and early detection. By setting a low monetary threshold, a firm ensures that even a relatively minor default on an external obligation gives it the option to terminate its own exposure. This strategy is often employed with counterparties that are perceived as higher risk, are less transparent, or operate in volatile sectors. It provides a “tripwire” that alerts the firm to the first signs of financial difficulty, allowing it to exit the relationship before a small problem becomes a catastrophic failure. The downside of this strategy is the risk of “false positives,” where a minor, manageable issue at the counterparty triggers a default, potentially destroying a valuable long-term relationship over a non-systemic event.

- The High Threshold Strategy This approach prioritizes relationship stability and avoids overreacting to market noise. A high threshold is set at a level that would only be breached by a truly existential threat to the counterparty’s solvency. This strategy is suitable for high-quality, systemically important counterparties with whom the firm has a deep and multifaceted relationship. It shows a degree of trust and prevents the disruption of valuable trading lines due to minor or technical defaults elsewhere. The inherent risk is a delayed reaction. The firm sacrifices early warning signals for stability, meaning that by the time the threshold is breached, the counterparty’s situation may have deteriorated so severely that recovery of funds is already compromised.

How Is the Threshold Measured for Different Instruments?

A critical strategic consideration is the methodology used to measure the amount of the defaulting debt, especially when applying cross-default provisions to complex financial instruments like derivatives. The traditional concept of “principal amount” is ill-suited for these transactions.

For standard loans and bonds, or “Specified Indebtedness,” the calculation is straightforward. The threshold is compared against the outstanding principal amount of the defaulted debt. This provides a clear, unambiguous figure. The complexity arises when the cross-default clause is expanded to cover “Specified Transactions,” which include swaps, options, and other OTC derivatives.

For these, there is no principal amount in the traditional sense. A firm and its counterparty must therefore agree on a different metric to measure the size of a default.

The application of a cross-default threshold to derivatives requires moving beyond simple principal amounts to more dynamic measures of exposure.

The strategic choice of metric is vital. A common approach is to use the mark-to-market (MTM) value of the terminated derivative positions. This reflects the current replacement cost of the transaction.

Another, more sophisticated approach is to use a measure of potential future exposure (PFE), which models the likely worst-case exposure over the life of the transaction. The choice of metric has a direct impact on the likelihood of a breach and must be carefully modeled and negotiated.

| Firm Profile | Typical Counterparty | Strategic Rationale | Preferred Threshold Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Macro Hedge Fund | Emerging Market Bank | High-risk environment requires an early warning system. Prioritizes capital preservation over relationship stability. | Low (e.g. $5M – $10M) |

| Corporate Treasury | Major Money Center Bank | Relationship is critical for daily operations. Seeks stability and avoids triggers from non-systemic events. | High (e.g. 2-3% of counterparty’s shareholder equity) |

| Pension Fund | Asset Manager (for derivatives hedging) | Moderate risk tolerance. Seeks protection but needs to maintain long-term hedging relationships. | Medium (e.g. a fixed amount like $25M or 1% of equity) |

| Proprietary Trading Firm | Another Trading Firm | High-velocity trading environment. Needs to react quickly to any sign of weakness in a counterparty with similar market exposure. | Low and tied to Net MTM Exposure |

Execution

The execution of a cross-default threshold strategy moves from theoretical calibration to operational reality. It requires the integration of legal negotiation, technological systems, and rigorous monitoring protocols. The effectiveness of the threshold as a risk mitigation tool depends entirely on the firm’s ability to execute these functions with precision and speed. A perfectly calibrated threshold is useless if the firm lacks the operational capacity to detect a breach and act upon it in a timely manner.

The Operational Playbook Implementing and Monitoring

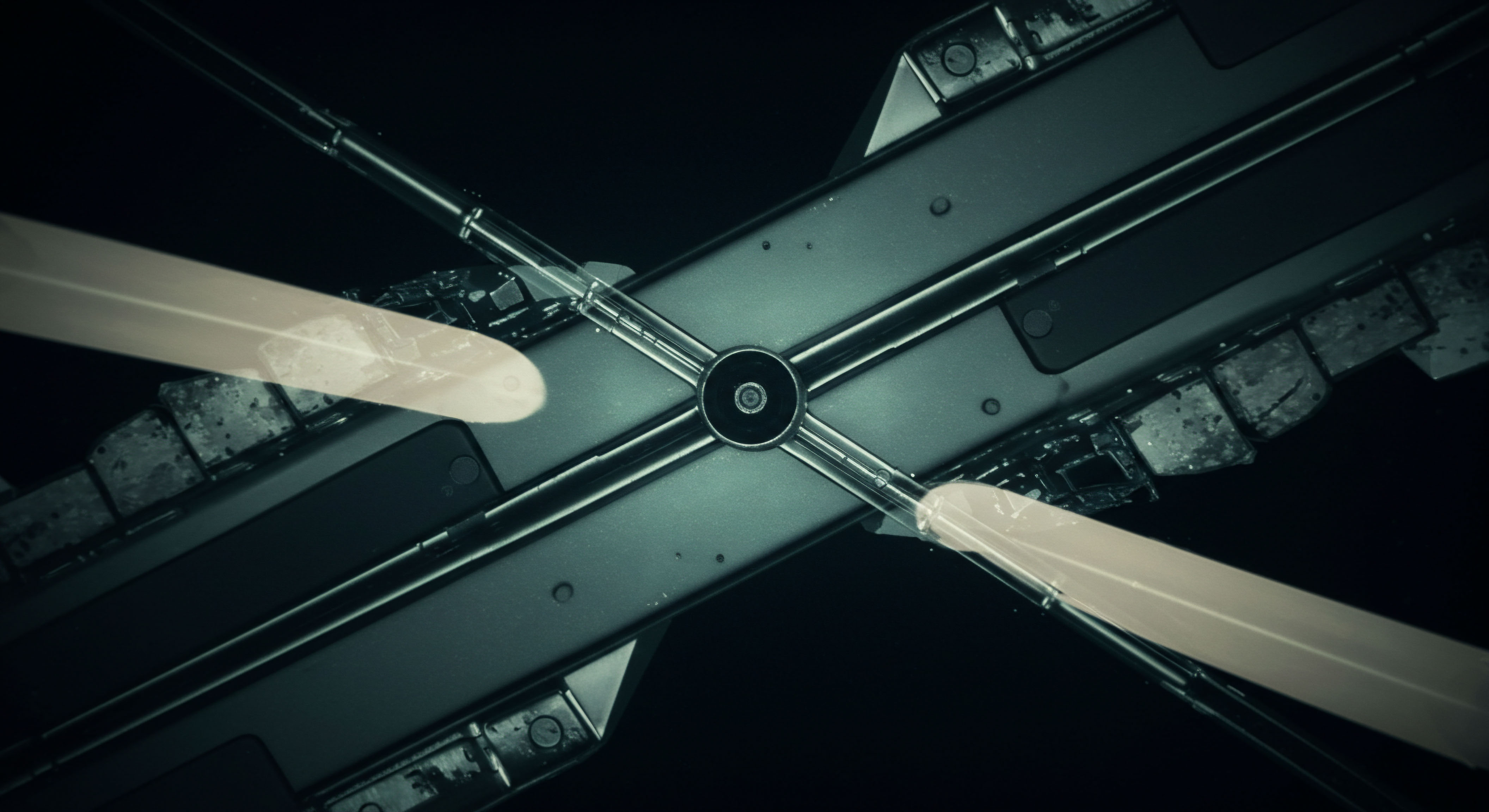

Implementing a cross-default monitoring system is a multi-stage process that combines legal diligence, systems architecture, and active risk management. It is a continuous cycle, not a one-time setup.

- Counterparty Due Diligence and Negotiation Before any agreement is signed, the risk team must conduct a thorough analysis of the potential counterparty’s capital structure, existing debt covenants, and overall financial health. This analysis directly informs the negotiation of the ISDA Master Agreement and its Credit Support Annex (CSA). The negotiation phase is where the threshold amount, its currency, and the precise definition of “Specified Indebtedness” and “Specified Transactions” are legally codified. This requires close collaboration between the legal, risk, and business teams.

- System Integration and Configuration Once the agreement is executed, the specific parameters must be programmed into the firm’s risk management system. This involves creating a unique counterparty profile and inputting the exact threshold amount and the scope of debt to be monitored. The system must be capable of distinguishing between different types of obligations and applying the correct measurement methodology (e.g. principal amount vs. MTM exposure).

- Continuous Monitoring Protocol The firm must establish a protocol for monitoring its counterparties for potential breach events. This is not a passive activity. It requires the use of automated data feeds that scan for credit-related news, rating agency downgrades, and public filings that might indicate a default. For significant counterparties, this may also involve monitoring the market price of their publicly traded debt or credit default swaps (CDS) for signs of distress.

-

Trigger Event Protocol A clear, pre-defined protocol must be in place for when a monitoring system flags a potential breach. This protocol dictates the immediate sequence of actions:

- An automated alert is sent to the primary risk officer and legal counsel.

- The risk team immediately verifies the authenticity of the default event using multiple sources.

- Legal counsel reviews the specific language of the governing ISDA agreement to confirm the breach and the firm’s rights.

- A decision is made by senior management on whether to exercise the right to terminate, based on the severity of the breach and the overall relationship with the counterparty.

- If termination is chosen, the operations team executes the necessary steps to close out positions, calculate final settlement amounts, and make demands on collateral.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

The execution of a sophisticated cross-default strategy relies on robust quantitative analysis. This involves not only setting the initial threshold but also understanding its impact under various market stress scenarios. Firms must model how different types of events would affect their net exposure and whether their chosen threshold provides adequate protection.

A well-executed strategy requires quantitative models that can simulate the financial impact of a threshold breach before it happens.

The table below illustrates a scenario analysis for a hypothetical firm, “Orion Capital,” managing its exposure to various counterparties. It shows how the interplay between the threshold amount, the nature of the default, and existing collateral determines the firm’s actions and ultimate financial outcome.

| Counterparty | Defaulting Debt (Specified Indebtedness) | Threshold Amount | Breach Occurred? | Our Net Exposure (MTM) | Collateral Held | Action Taken | Financial Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apex Solutions | $15M bond payment failure | $25M | No | $5M | $2M | Continue monitoring | None; risk is noted |

| Tiberium Financial | $60M loan acceleration | $50M | Yes | $30M | $20M | Immediate termination & collateral seizure | $10M residual exposure; legal claim filed |

| Legacy Industries | Technical covenant breach (no payment default) | $100M | No (as no payment default) | -$12M (Owed by Orion) | $0 | Monitor closely; contact counterparty for clarification | None; relationship maintained |

| Quantum Leap Fund | Failure to pay on a derivative (Specified Transaction) | $5M (measured by MTM) | Yes (MTM of default was $8M) | $12M | $15M | Immediate termination & collateral drawdown | Fully covered; $3M excess collateral returned |

Predictive Scenario Analysis a Case Study

Consider the case of two asset management firms, Firm A and Firm B, both holding significant derivatives positions with a regional bank, “Mercury Bank,” in early 2023. The market environment is becoming increasingly unstable due to rapid interest rate hikes.

Firm A, in its ISDA agreement with Mercury Bank, had negotiated a cross-default threshold of $50 million. Their rationale was based on a historical analysis of bank failures, and they believed this level represented a truly systemic event. Firm B, having a more cautious risk framework, had set its threshold at a much lower $15 million. They also expanded the definition of “Specified Indebtedness” to include the failure to post collateral on any derivatives transaction with any other counterparty for more than two business days.

In March 2023, a rumor circulates that Mercury Bank has suffered significant losses in its hold-to-maturity bond portfolio. While the bank remains solvent, one of its smaller hedge fund counterparties panics and pulls its financing lines. This forces Mercury Bank into a technical default on a small, $20 million private loan that it is unable to roll over due to the sudden liquidity crunch. The bank’s management views this as a minor issue that will be resolved within a week.

For Firm A, nothing happens. The $20 million default is well below its $50 million threshold. Their risk team notes the event but takes no action, respecting the high threshold designed to ignore such “minor” disruptions. They continue their trading relationship as normal.

For Firm B, the situation is entirely different. The $20 million default immediately breaches their $15 million threshold. Their risk system fires an automated alert to the Chief Risk Officer. Within hours, their legal team confirms the breach and their rights under the ISDA agreement.

Firm B’s portfolio with Mercury Bank has a positive net mark-to-market value of $35 million, against which they hold $30 million in collateral. They immediately issue a termination notice. They close out all their positions at the current market value and seize the $30 million in collateral, leaving them with a manageable unsecured claim of $5 million against Mercury Bank.

A week later, the rumors about Mercury Bank’s bond portfolio are confirmed to be true, and the losses are far larger than anticipated. A full-blown bank run occurs. The regulators step in over the weekend and place the bank into receivership. Firm A, which took no action, now finds all its contracts with Mercury Bank frozen.

Their net exposure of $40 million is now a deeply subordinated claim in a lengthy bankruptcy proceeding, with recovery prospects estimated at less than 10 cents on the dollar. Firm B’s decisive action, enabled by its more sensitive and carefully constructed threshold, allowed it to crystallize its position and protect its capital before the catastrophic failure, turning a potential $40 million loss into a much smaller $5 million one.

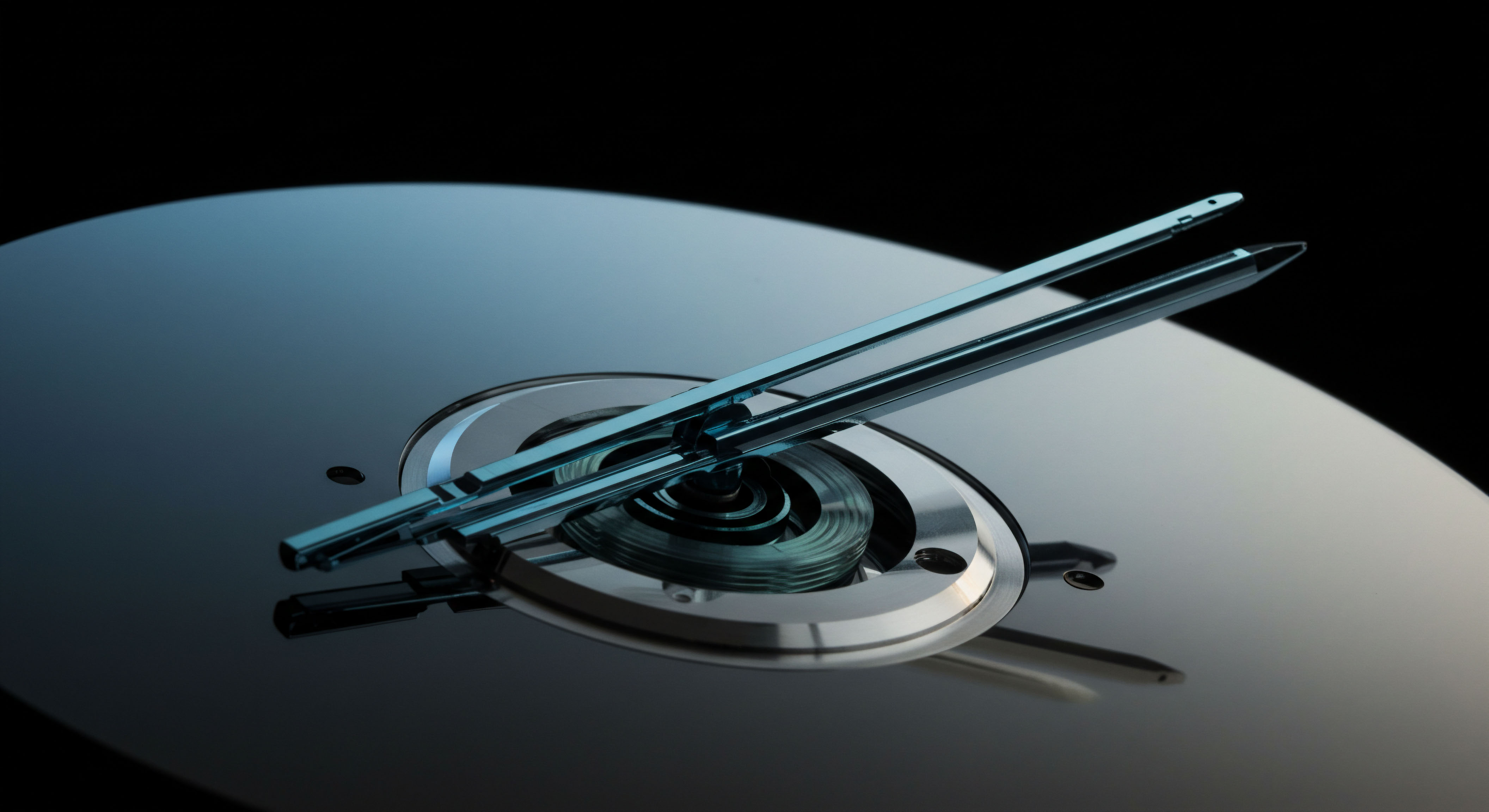

System Integration and Technological Architecture

Effective execution is impossible without a supporting technological architecture. This system is responsible for the flow of information and the automation of monitoring that enables a firm to act decisively.

- Data Feeds The foundation of the system is a constant stream of high-quality data. This includes real-time feeds from services like Bloomberg, Reuters, and other financial information providers. These feeds supply critical information on credit ratings, bond prices, news sentiment, and public filings (like SEC EDGAR reports) for all counterparties.

- Risk Engine This is the computational core of the architecture. The risk engine aggregates all transaction data for a given counterparty from the firm’s own trading systems. It calculates the net exposure in real-time, accounts for the value of any posted collateral, and continuously compares the known credit events of the counterparty against the pre-configured threshold amounts stored in its database. This engine must be powerful enough to handle complex calculations, such as Potential Future Exposure, for large portfolios.

- Alerting and Workflow System When the risk engine detects a breach, it must trigger an automated workflow. This system sends secure, detailed alerts to the relevant personnel in the risk, legal, and trading departments. The system should also create a case file, logging all relevant data, communications, and decisions for audit and compliance purposes. This ensures that the response to a critical event is structured and auditable, not ad-hoc and chaotic.

References

- “Cross Default – ISDA Provision – The Jolly Contrarian.” The Jolly Contrarian, 14 Aug. 2024.

- “Transactional Corner ▴ Cross-Default (Under Specified Transactions?) ▴ Drafting Considerations Related to a “Compound” Event of Default.” JD Supra, 18 Jan. 2024.

- “Cross Default ▴ Cross Default Scenarios ▴ Understanding the Domino Effect in Finance.” LinkedIn, 10 Apr. 2025.

- “Cross Default ▴ Definition, How It Works, and Consequences.” Investopedia.

- “Counterparty Risk.” AnalystPrep.

Reflection

The knowledge of how a cross-default threshold operates is a component part of a larger system of institutional risk intelligence. The true strategic question moves beyond the calibration of a single clause in an agreement. It prompts a deeper introspection into a firm’s entire operational framework. Does your current architecture treat these thresholds as static legal artifacts, reviewed only during contract negotiation?

Or does it integrate them as dynamic, living parameters within a real-time system that monitors, models, and provides actionable intelligence? The answer reveals the fundamental difference between a firm that simply documents risk and one that actively manages it, possessing the structural advantage to act with precision and control in moments of market-wide distress.

Glossary

Cross-Default Threshold

Counterparty Risk Exposure

Specified Indebtedness

Threshold Amount

Counterparty Risk

Risk Management

Isda Master Agreement

Credit Support Annex

Potential Future Exposure