Concept

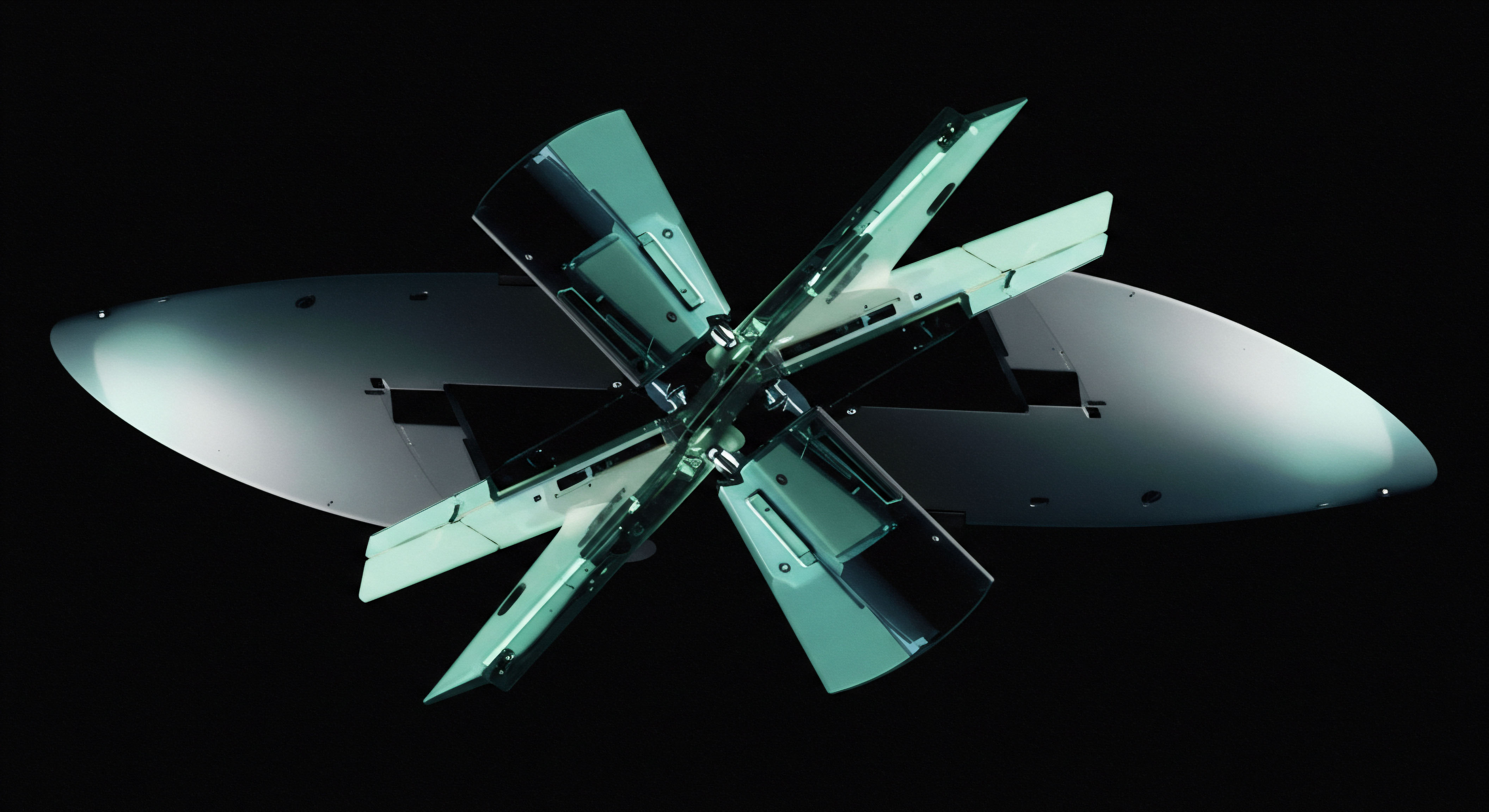

The transition from a bilateral to a centrally cleared architecture for over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives represents a fundamental re-engineering of market risk. Your direct experience in a pre-mandate environment involved managing a complex, distributed web of counterparty exposures, where each trading relationship was a discrete universe of risk, documentation, and collateralization. Central clearing collapses this distributed network into a hub-and-spoke model. The central counterparty (CCP) becomes the system’s new gravitational center, fundamentally altering the physics of how risk is priced and how liquidity behaves.

This shift is an architectural one. The CCP inserts itself into the transaction through a process of novation, becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. This act dissolves the direct credit linkage between the original counterparties. The operational reality is that your exposure is no longer to a diverse portfolio of trading partners but is concentrated into a single, highly regulated entity designed to absorb and manage default risk.

Understanding this new architecture is the prerequisite to exploiting its properties. The core function of the CCP is to manage the counterparty credit risk that was previously a bilateral concern. It achieves this by erecting a fortress of pre-funded financial resources, built primarily from the margin contributions of its clearing members.

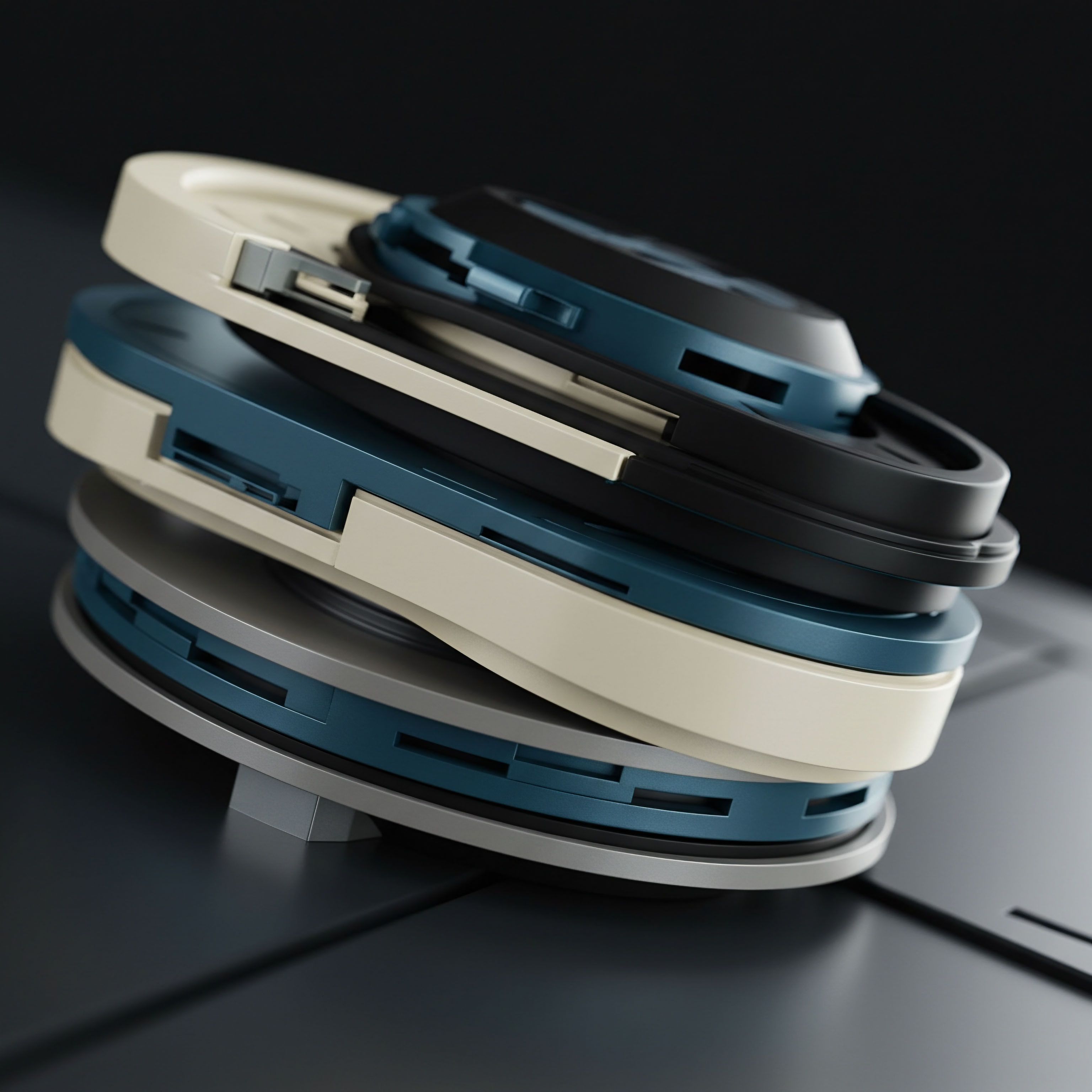

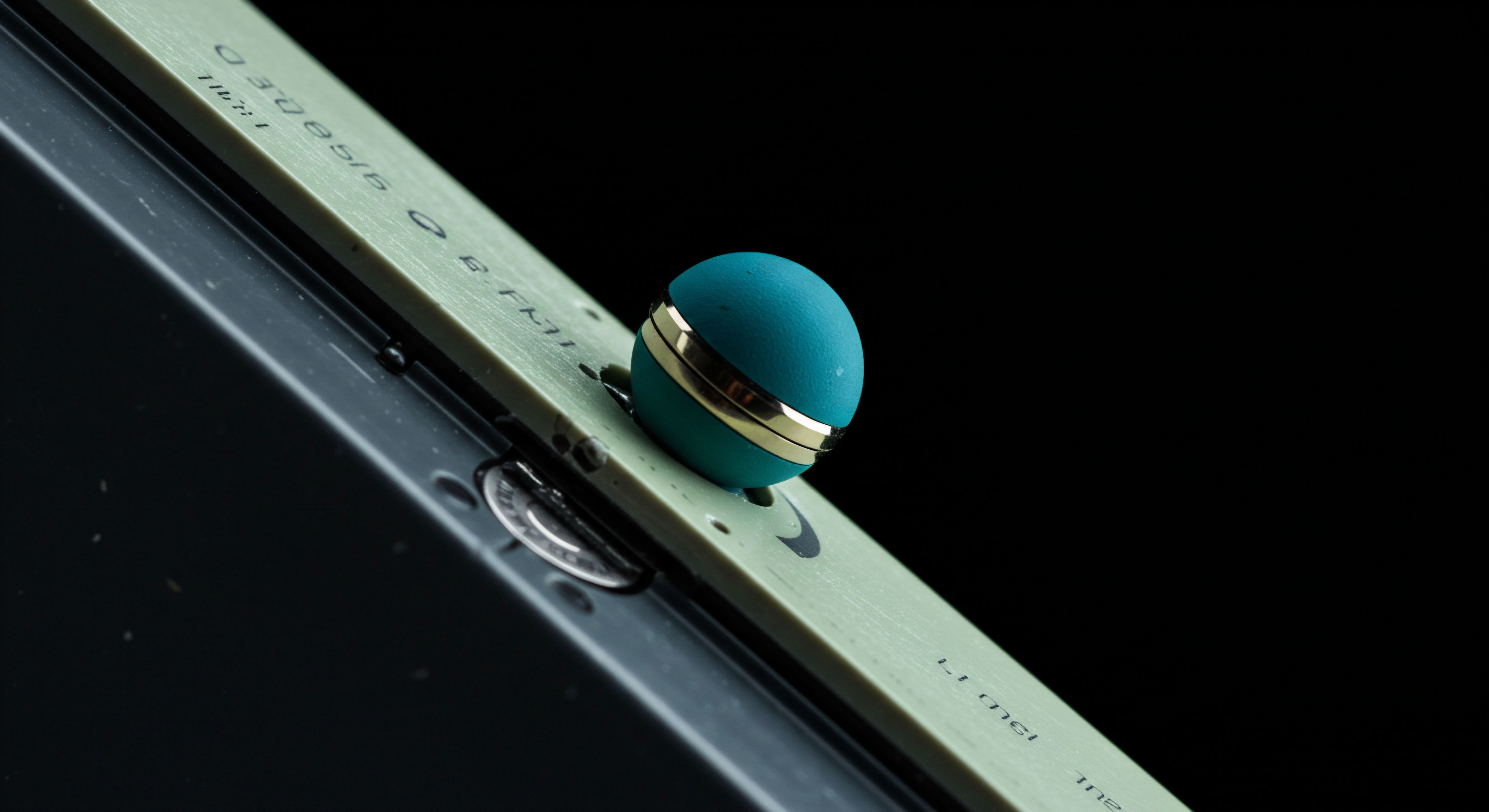

Central clearing re-architects the OTC market by replacing a web of bilateral credit exposures with a centralized hub-and-spoke system managed by a CCP.

The implications of this structural change are profound and systemic. The system standardizes not just the contracts themselves but also the protocols for risk management. Daily, and often intra-day, marking-to-market and the associated flow of variation margin create a high-frequency cash flow reality that is far more intensive than traditional bilateral collateralization schedules. This standardized process creates a uniform language for risk, allowing for greater fungibility and interoperability between market participants who adopt it.

The entire system is designed to prevent the catastrophic failure of a single participant from triggering a cascade of defaults, a primary objective born from the 2008 financial crisis. The introduction of a CCP transforms the nature of risk from an idiosyncratic, counterparty-specific variable into a standardized, system-level parameter.

Strategy

Strategically navigating the centrally cleared environment requires a dual focus on the explicit costs introduced by the CCP and the second-order effects on market liquidity. The pricing of a derivative is no longer a simple negotiation of its market value plus a qualitative assessment of counterparty risk. It is now an explicit, multi-component calculation dictated by the CCP’s risk management framework. Concurrently, liquidity has become bifurcated, concentrating in standardized, cleared products while potentially receding from the bespoke, bilateral space.

The New Economics of Derivative Pricing

Central clearing dismantles the traditional model of pricing counterparty risk, which was encapsulated in Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA) and Debit Valuation Adjustment (DVA). Instead, it erects a new cost structure based on transparent, operationalized fees and collateral requirements. This transforms risk pricing from a complex modeling exercise into a direct, tangible cost of trading.

The primary components of this new pricing equation are:

- Initial Margin (IM) ▴ A good-faith deposit posted by both parties, calculated by the CCP to cover potential future losses in the event of a member’s default over a specified close-out period. This is the most significant cost component, as it requires posting high-quality liquid assets that could otherwise be used for other purposes. The CCP’s IM models are typically based on Value-at-Risk (VaR), meaning more volatile and less liquid instruments incur higher margin requirements.

- Variation Margin (VM) ▴ The daily, or even intra-day, cash settlement of gains and losses on a derivatives portfolio. While not a net cost over the life of the trade, the operational friction and funding requirements for meeting VM calls are a material consideration.

- Default Fund Contributions ▴ Clearing members must contribute to a mutualized default fund, which acts as a secondary layer of protection after a defaulting member’s own resources are exhausted. This represents a long-term capital commitment and a contingent liability.

- Clearing Fees ▴ These are the direct, per-transaction fees charged by the CCP for its services. While typically the smallest component, they are a direct and unavoidable cost.

The table below provides a strategic comparison of the pricing inputs for a typical interest rate swap under both market structures.

| Pricing Component | Bilateral (Non-Cleared) Environment | Centrally Cleared Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Counterparty Risk | Priced via CVA/DVA; a complex, model-driven calculation of expected loss due to counterparty default. Highly bespoke to each counterparty. | Replaced by Initial Margin, Default Fund contributions, and clearing fees. The cost is standardized, transparent, and directly tied to the CCP’s risk model. |

| Funding Cost | Funding Valuation Adjustment (FVA) arises from the cost of funding collateral for uncollateralized or imperfectly collateralized trades. | FVA is still present but is now driven by the cost of financing high-quality liquid assets required for Initial Margin and meeting daily Variation Margin calls. |

| Operational Overhead | High costs associated with negotiating legal documents (ISDA Master Agreements, CSAs) and managing bespoke collateral agreements with each counterparty. | Reduced legal overhead per trade, but increased operational intensity related to daily margining, collateral management, and CCP reporting. |

| Price Transparency | Low. Prices are discovered bilaterally, leading to wider bid-ask spreads and information asymmetry. | High. For standardized products, cleared markets offer greater price transparency, which generally leads to tighter bid-ask spreads. |

How Does Central Clearing Reshape Market Liquidity?

The impact of central clearing on liquidity is not uniform. It acts as a powerful catalyst, concentrating liquidity in certain areas while drawing it away from others. This creates a more heterogeneous liquidity landscape that must be navigated with precision.

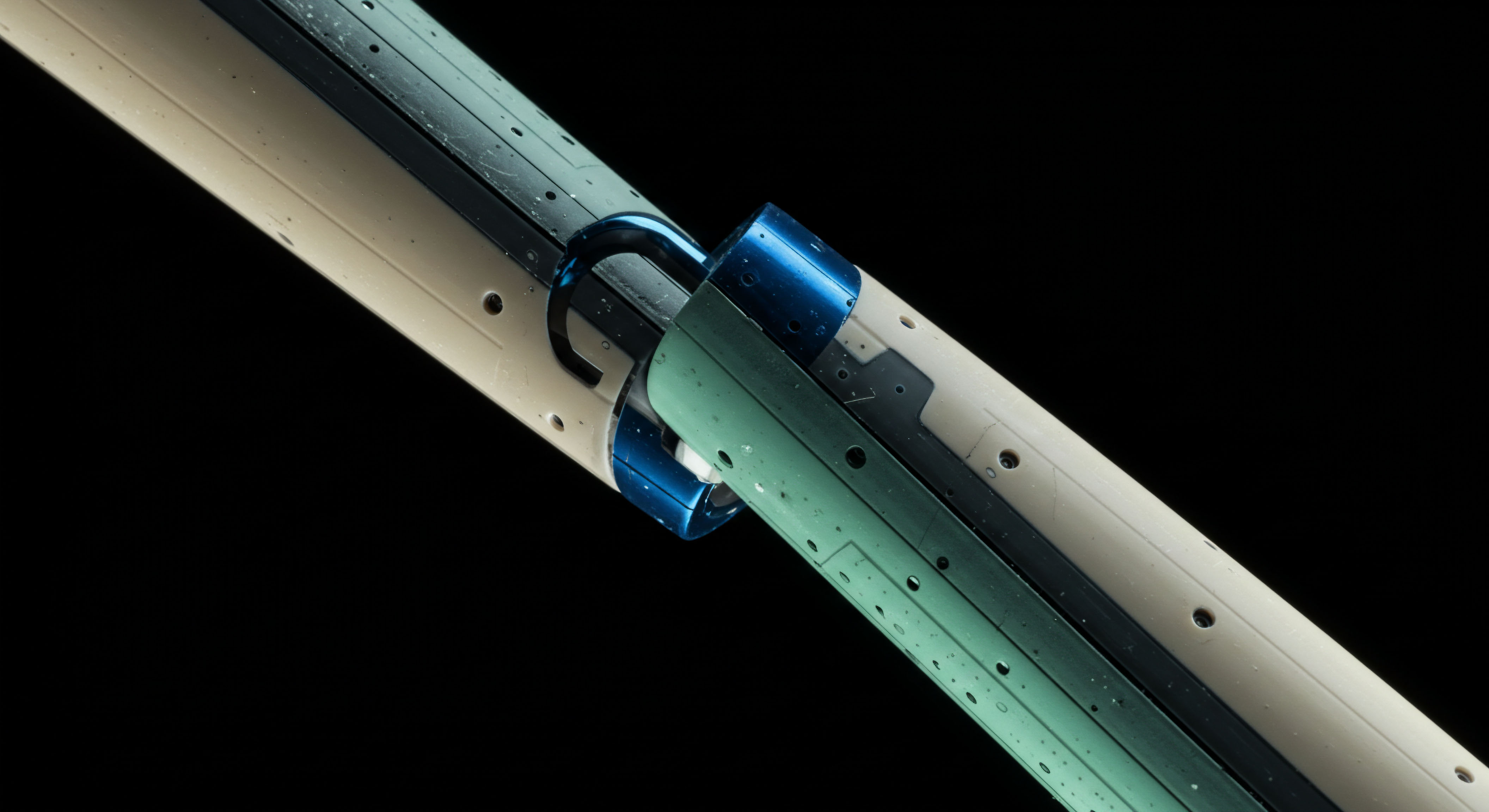

The mandate for central clearing has bifurcated the derivatives market, leading to deep liquidity pools for standardized contracts while potentially stranding complex, non-clearable instruments.

On one hand, clearing enhances liquidity for standardized products. By mitigating counterparty risk, it makes these instruments more fungible and attractive to a broader base of market participants. The reduction in risk lowers the barrier to entry for many firms, increasing the number of potential counterparties and deepening the pool of available liquidity. Regulatory mandates, such as those in the Dodd-Frank Act, further reinforce this by making non-cleared trades more expensive from a capital perspective, effectively pushing volume into the cleared space.

On the other hand, this very success creates two strategic challenges. First, it leads to market fragmentation. Liquidity for highly customized, complex derivatives that are ineligible for clearing may diminish as the bulk of trading activity migrates to standardized contracts. This can increase the cost and difficulty of hedging unique or exotic risks.

Second, the risk management practices of CCPs themselves introduce a new, systemic form of liquidity risk. CCPs’ margin models are inherently procyclical; in times of market stress and heightened volatility, margin requirements increase sharply across the system. This can trigger a sudden, widespread demand for high-quality collateral, potentially creating a liquidity squeeze precisely when it is most needed. This systemic liquidity demand is a new feature of the market architecture and a critical consideration for any institutional risk framework.

Execution

Executing within a centrally cleared framework shifts the operational focus from counterparty due diligence to the precise mechanics of margin and default management. The CCP’s rulebook is the new governing law, and its risk models are the primary determinants of trading costs. Mastering execution in this environment means understanding these systems at a granular level and integrating them into every stage of the trading lifecycle, from pre-trade analytics to post-trade collateral optimization.

The Operational Impact of Margin Calculation

The calculation of Initial Margin (IM) is the most critical execution detail. It is the mechanism by which the CCP translates the theoretical risk of a portfolio into a direct, upfront funding requirement. Most CCPs utilize sophisticated Value-at-Risk (VaR) models, such as historical simulation or filtered historical simulation, to determine the appropriate level of IM.

These models typically aim for a high confidence level (e.g. 99.5% or 99.7%) over a specific close-out period (e.g. five days for cleared swaps).

From an execution standpoint, this has several direct consequences:

- Portfolio-Level Offsets ▴ IM is calculated at the portfolio level, not on a trade-by-trade basis. This means that new trades that are risk-reducing from the CCP’s perspective can lower the overall IM requirement. Pre-trade analysis tools that can accurately forecast the marginal IM impact of a new position are essential for efficient execution and capital usage.

- Asset Eligibility and Haircuts ▴ The type of collateral posted as IM is critical. CCPs accept a range of assets but apply haircuts based on the asset’s perceived credit quality and liquidity. Posting cash typically involves no haircut, while government bonds or corporate bonds will have their value reduced for margin purposes. Optimizing the portfolio of assets used as collateral is a key operational discipline.

- Procyclicality in Practice ▴ During a market crisis, two factors will conspire to dramatically increase IM requirements. First, the increase in realized volatility will directly feed into the CCP’s VaR model, raising the calculated margin. Second, a flight to quality may decrease the value of non-cash collateral, forcing firms to post additional assets. An execution framework must account for this contingent liquidity demand.

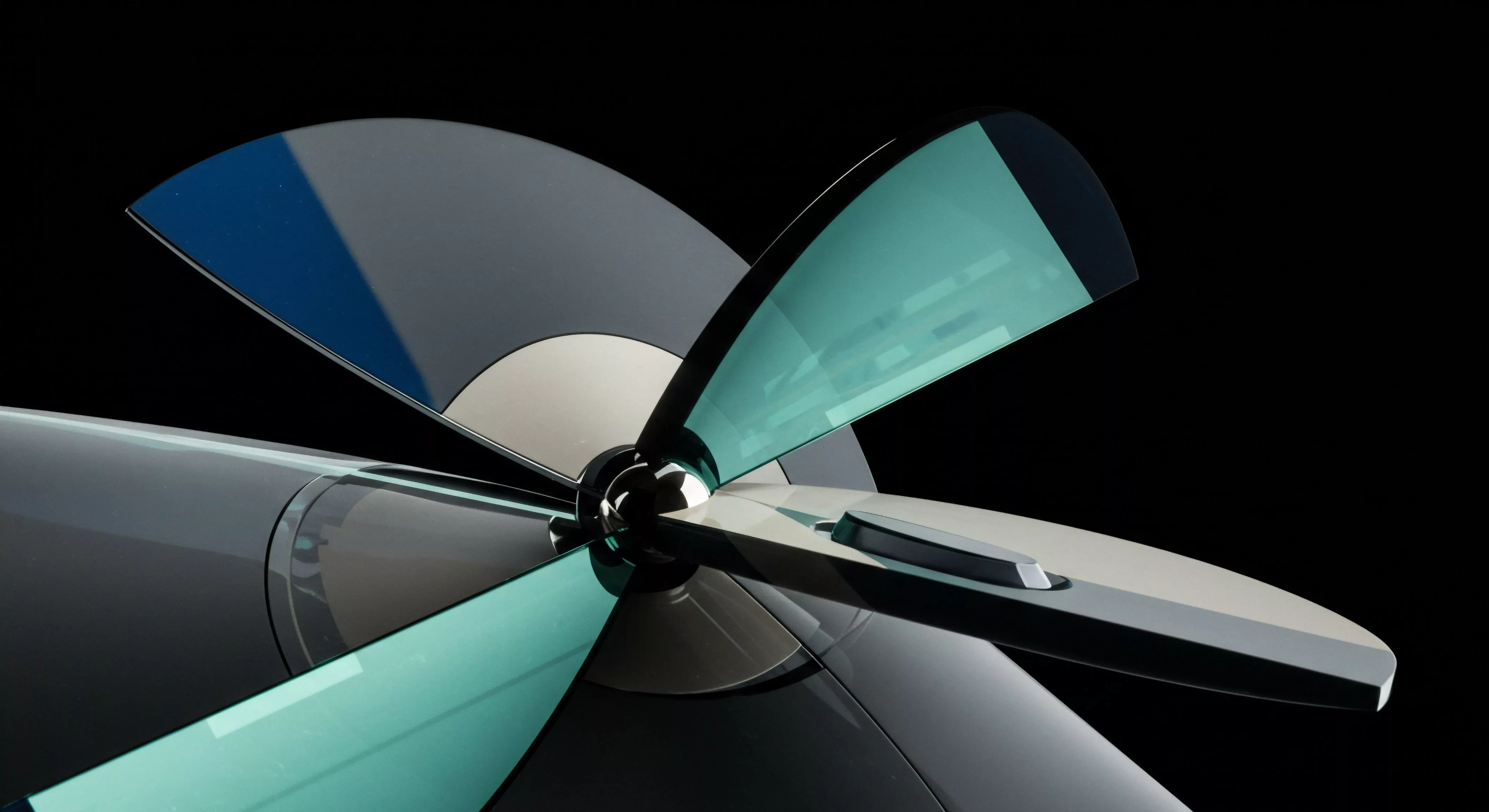

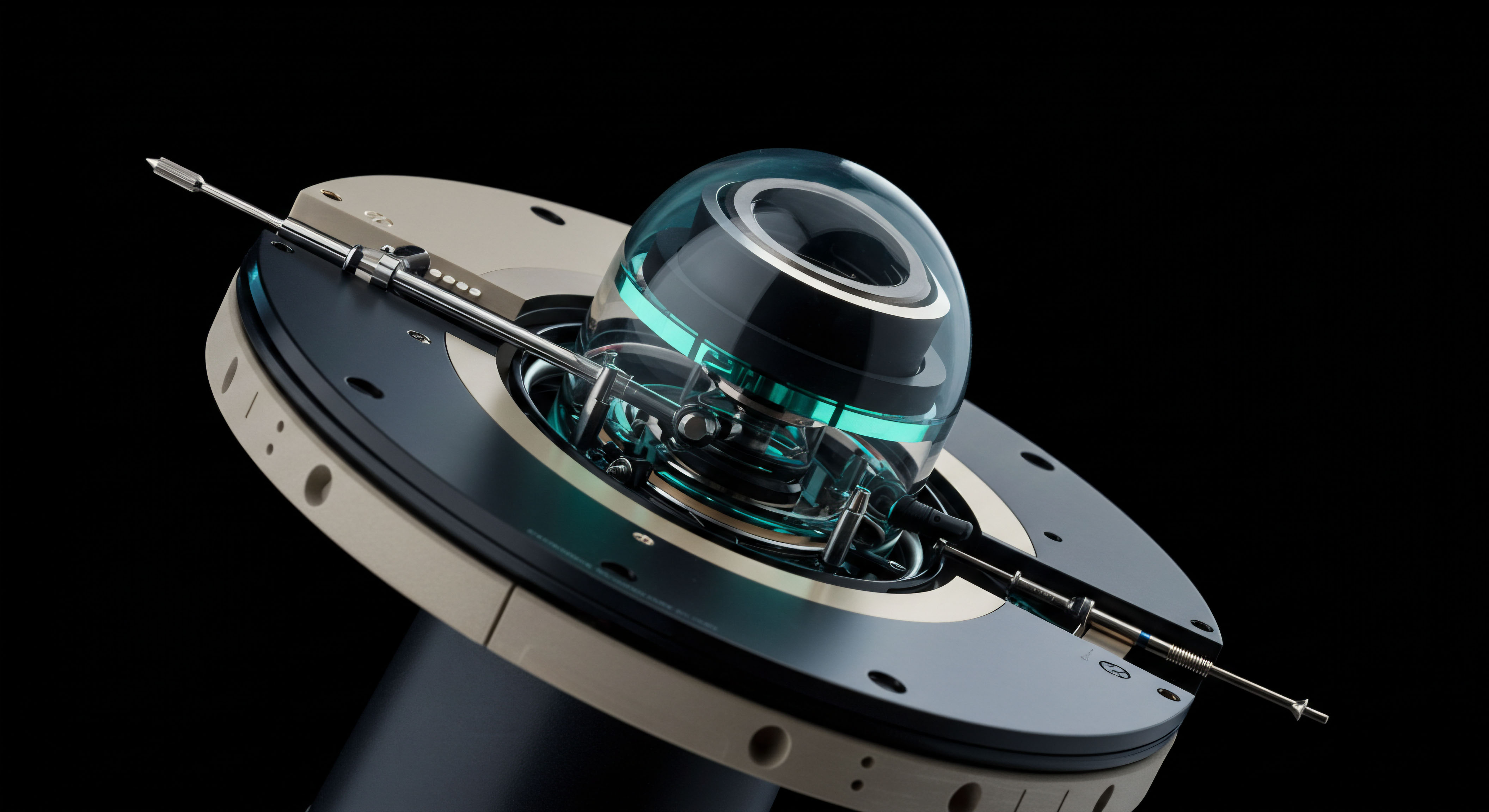

The Default Waterfall a Mutualized Risk System

While a CCP default is a remote tail-risk event, the structure of its default waterfall is a core component of the system’s pricing and risk profile. It represents a system of mutualized insurance among the clearing members. Understanding its layers is essential for any firm that is a direct clearing member.

The typical waterfall structure is as follows:

- Layer 1 ▴ The defaulting member’s posted Initial Margin.

- Layer 2 ▴ The defaulting member’s contribution to the Default Fund.

- Layer 3 ▴ The CCP’s own capital contribution, often called “skin-in-the-game.”

- Layer 4 ▴ The surviving clearing members’ contributions to the Default Fund.

- Layer 5 ▴ Additional assessments on surviving clearing members, up to a capped amount.

The risk to a surviving member is concentrated in Layers 4 and 5. This exposure can be thought of as a contingent liability or the premium paid for the mutualized insurance provided by the CCP. Quantifying this exposure, often termed the Central Clearing Valuation Adjustment (CCVA), is a complex analytical challenge but a necessary one for a complete understanding of the risks involved.

Quantitative Cost Comparison a Hypothetical Swap

To illustrate the practical cost differences, consider a hypothetical $100 million notional, 5-year interest rate swap. The table below models the potential cost components in both a bilateral and a cleared framework. The figures are illustrative and demonstrate the structural differences in cost attribution.

| Cost Component | Bilateral Scenario (Indicative) | Centrally Cleared Scenario (Indicative) | Governing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit Valuation Adj. (CVA) | $250,000 (25 bps) | $0 | Bilateral counterparty credit model. |

| Initial Margin (IM) | $1,500,000 (Under bilateral margin rules) | $1,000,000 (Based on CCP VaR model) | Regulatory Rules vs. CCP Model. |

| Annual Funding Cost of IM (at 2%) | $30,000 | $20,000 | Firm’s cost of funds. |

| Default Fund Contribution | $0 | $150,000 (One-time, held by CCP) | CCP membership requirements. |

| Annual Clearing & Other Fees | $0 | $5,000 | CCP fee schedule. |

| Total Upfront Capital/Collateral | $1,500,000 | $1,150,000 | Sum of IM and DF contributions. |

This simplified model demonstrates how central clearing shifts the cost from an abstract CVA calculation to concrete, funded amounts for IM and the Default Fund. While the total collateral outlay might be lower in the cleared scenario due to portfolio netting benefits, the costs are explicit and require active liquidity management.

References

- Duffie, Darrell, and Henry T. C. Hu. “The ISDA master agreement and clearinghouse rules for OTC derivatives.” The Journal of Legal Studies 49.S1 (2020) ▴ S115-S146.

- Cont, Rama, and Rui Fan. “The impact of central clearing on counterparty risk, and the determinants of clearing rates.” SSRN Electronic Journal (2013).

- Arnsdorf, Matthias. “Central counterparty CVA.” Risk Magazine (2019).

- Borio, Claudio, Robert N. McCauley, and Patrick McGuire. “Clearing risks in OTC derivatives markets ▴ the CCP-bank nexus.” BIS Quarterly Review (2017).

- Loon, Y. C. and Zhaodong Zhong. “Does Dodd-Frank affect OTC transaction costs and liquidity? Evidence from real-time CDS trade reports.” Journal of Financial Economics 121.3 (2016) ▴ 625-649.

- Ghamami, Samim, and Paul Glasserman. “Central clearing and systemic liquidity risk.” International Journal of Central Banking (2021).

- Pirrong, Craig. “The economics of central clearing ▴ Theory and practice.” ISDA Discussion Papers Series 1 (2011).

- Hull, John C. “The credit, funding, and debit value adjustment.” The Journal of Credit Risk 12.3 (2016) ▴ 1-18.

- Brigo, Damiano, and Massimo Morini. “Counterparty risk and CVA ▴ A financial engineering perspective.” Risk Books (2012).

- Skeel, David. “The enduring legacy of the Dodd-Frank Act’s derivatives reforms.” Capital Markets Law Journal 15.4 (2020) ▴ 409-420.

Reflection

The architectural shift to central clearing has established a new operational reality. The system is designed for stability, standardizing risk through transparent protocols and mutualized backstops. This structure provides a powerful foundation for managing systemic risk. Yet, it also introduces new dynamics ▴ the procyclical demand for liquidity, the bifurcation of the market, and the concentration of risk at the CCP.

The essential question for your framework is no longer simply “who is my counterparty?” but “how does my portfolio interact with the clearinghouse system?” How does your operational infrastructure anticipate and manage the contingent liquidity demands inherent in this new architecture? The ultimate strategic advantage lies in building a system that not only complies with these new protocols but deeply understands their mechanics to optimize capital, manage liquidity, and execute with precision.

Glossary

Centrally Cleared

Central Clearing

Clearing Members

Variation Margin

Counterparty Risk

Cva

Initial Margin

Default Fund

Dodd-Frank Act

Liquidity Risk

Default Waterfall