Concept

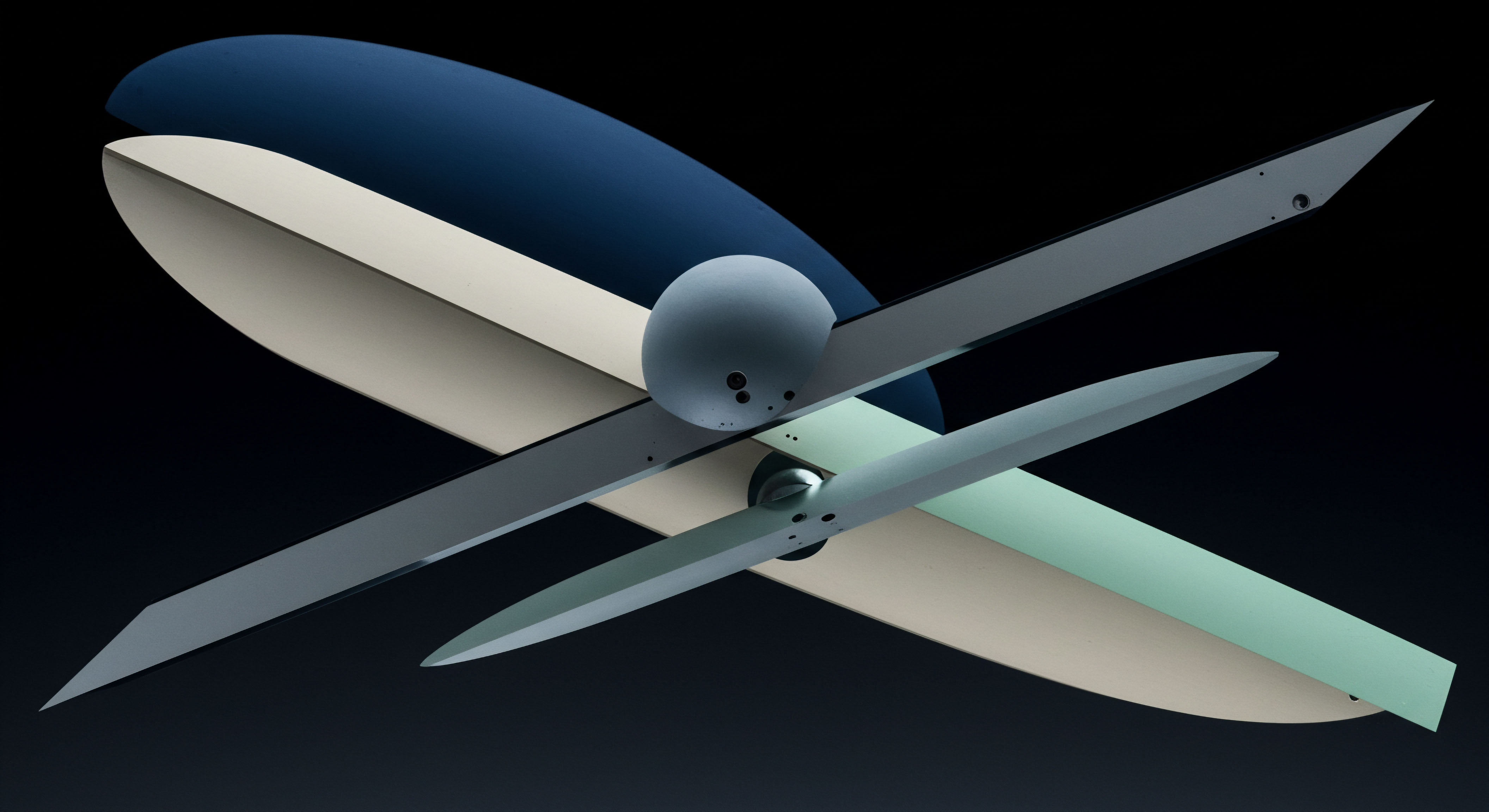

The integration of a central clearing counterparty (CCP) with a central limit order book (CLOB) represents a fundamental re-architecting of market structure. It systemically alters the flow of risk, capital, and information within the trading lifecycle. At its core, this synthesis addresses the foundational vulnerability of a purely bilateral CLOB environment which is counterparty risk. In a traditional CLOB, every matched order creates a direct, bilateral obligation between two anonymous participants.

The system’s integrity rests on the implicit assumption that both parties will fulfill their settlement obligations. A CCP removes this direct linkage. Through a process called novation, the CCP interposes itself between the buyer and the seller of every trade the moment it is executed. The original contract is extinguished and replaced by two new contracts ▴ one between the seller and the CCP, and another between the buyer and the CCP. The CCP becomes the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer.

This architectural shift has profound consequences for the cost of trading. The apparent cost structure of a CLOB, once dominated by explicit execution fees and the implicit cost of the bid-ask spread, expands to include a new set of risk-based pricing mechanisms. The CCP, now guaranteeing the performance of every trade, must quantify and collateralize the risk it assumes. This introduces the direct costs of clearing, most notably initial and variation margin.

Initial margin is a form of good-faith deposit, a performance bond posted by both parties to cover potential future losses in the event of a default. Variation margin is the daily, or even intraday, cash settlement of profits and losses on open positions. These margin requirements represent a direct funding cost for market participants. Capital that could have been deployed elsewhere is now encumbered as collateral, introducing a significant opportunity cost that must be factored into any trading strategy.

The systemic benefit conferred by the CCP is the mutualization of counterparty risk. The failure of a single large participant in a bilateral market can trigger a cascade of defaults, threatening the stability of the entire system. A CCP acts as a circuit breaker in this scenario. It absorbs the losses from a defaulting member using a predefined waterfall of financial resources.

This waterfall typically includes the defaulting member’s own margin, the CCP’s own capital, and a default fund contributed to by all clearing members. This mutualized guarantee fund is a form of insurance, and like any insurance, it comes with a premium. This premium is embedded in the overall cost of clearing, manifesting as clearing fees, default fund contributions, and the stringent capital requirements for membership. The cost of trading on a cleared CLOB, therefore, is a direct reflection of the price of systemic stability. It transforms an opaque, unpriced, and potentially catastrophic tail risk into a transparent, quantifiable, and ongoing operational cost.

Central clearing transforms latent counterparty risk into explicit, quantifiable costs through mechanisms like margin and default fund contributions.

This transformation of risk into cost has a significant impact on market behavior and liquidity dynamics. The requirement to post margin increases the cost of holding open positions, which can disincentivize certain types of speculative trading and reduce overall leverage in the system. For market makers, who provide liquidity by continuously quoting buy and sell prices, margin requirements increase the cost of carrying inventory. This can lead to wider bid-ask spreads as market makers demand higher compensation for the increased cost of their liquidity provision.

A study on Nordic equity markets found that the introduction of a CCP led to a decline in trading volume, suggesting that the increased costs can deter some market activity. The implementation of central clearing can also create a more resilient market structure, which may attract new participants who were previously deterred by the high counterparty risk of bilateral trading. The increased transparency and standardized risk management of a cleared market can lower the barriers to entry for some firms and promote greater competition among liquidity providers.

The architectural design of the clearing system itself becomes a critical determinant of cost. The models for accessing the CCP, such as direct clearing membership versus client clearing through a general clearing member (GCM), present different cost structures and operational burdens. Direct members bear the full cost and responsibility of maintaining their own clearing infrastructure and contributing to the default fund. Clients of a GCM pay fees for the service but are insulated from the direct operational complexities.

The choice of access model is a strategic decision for trading firms, balancing the direct costs of membership against the fees and potential dependencies associated with client clearing. The SEC’s expansion of clearing mandates in the US Treasury market highlights the importance of these access models, as firms must navigate the operational and cost implications of connecting to the clearing infrastructure. The presence of a single, dominant CCP versus a multi-CCP environment also impacts costs through the effects of competition and liquidity fragmentation. A multi-CCP model could foster competition and lower clearing fees, but it could also fragment liquidity and reduce the netting efficiencies that are a primary benefit of central clearing.

Strategy

Strategically evaluating the cost of trading on a centrally cleared CLOB requires a multi-dimensional analysis that extends far beyond the nominal execution fee. The introduction of a CCP fundamentally reframes the cost equation, shifting a significant portion of the expense from implicit, event-driven risks to explicit, ongoing operational costs. A sophisticated trading entity must dissect these costs into their constituent components to build a robust execution strategy. These costs can be broadly categorized into direct costs, indirect costs, and systemic costs, each with its own set of strategic considerations.

Deconstructing the Direct Cost Architecture

Direct costs are the most transparent and quantifiable expenses associated with cleared trading. They are the fees and funding requirements explicitly charged by the CCP and its members. The primary components are:

- Clearing Fees ▴ These are per-transaction or volume-based fees charged by the CCP for the service of novation, risk management, and settlement. They are analogous to an exchange’s execution fee but are specifically for the clearing function.

- Initial Margin (IM) ▴ This is the most significant direct cost for most participants. IM is a collateral deposit required to cover potential future exposure in the event of a member’s default. The amount of IM is calculated by the CCP using complex risk models, such as SPAN (Standard Portfolio Analysis of Risk) or a value-at-risk (VaR) based methodology. The cost of IM is the funding cost of the assets posted as collateral, which could be cash or high-quality liquid securities. A firm must analyze the opportunity cost of this encumbered capital.

- Variation Margin (VM) ▴ This is the daily, or sometimes intraday, settlement of profits and losses on open positions. While not a cost in the traditional sense, the need to meet VM calls requires a highly efficient treasury function and access to liquidity, which has an associated operational cost. Failure to meet a VM call can trigger a default.

- Default Fund Contributions ▴ Clearing members are required to contribute to a mutualized default fund, which acts as a layer of protection for the CCP after a defaulting member’s margin is exhausted. This contribution represents capital that is tied up and at risk, and its cost must be amortized across the firm’s trading activities.

A strategic approach to managing these direct costs involves optimizing collateral usage. Firms can employ collateral transformation services to convert less liquid assets into eligible collateral, albeit for a fee. They can also engage in portfolio margining, where the IM for a portfolio of correlated positions is calculated on a net basis, potentially reducing the total margin requirement compared to calculating it for each position individually.

The strategic management of trading costs on a cleared CLOB pivots from managing execution slippage to optimizing collateral and funding efficiency.

Analyzing the Indirect and Systemic Cost Implications

Indirect costs are less transparent but can have an equally significant impact on profitability. These costs arise from the way central clearing alters market dynamics and capital allocation.

One of the most significant indirect costs is the impact on liquidity and the bid-ask spread. As market makers must now fund margin for their inventory, their cost of providing liquidity increases. This cost is invariably passed on to liquidity takers in the form of wider spreads.

A firm’s strategy must account for this potential increase in implicit trading costs. A study on the introduction of CCPs in Nordic equity markets showed a decline in trading volume, which can be partially attributed to these increased costs of liquidity provision.

Another critical indirect cost is the impact on balance sheet capacity. For bank-affiliated dealers, bilateral trades consume balance sheet space due to regulatory capital requirements like the leverage ratio. Central clearing allows for the netting of exposures, which can significantly reduce the balance sheet impact of a given set of trades. This can free up capacity for additional market-making or proprietary trading.

The cost of not using central clearing, in this context, is the opportunity cost of this constrained balance sheet capacity. The SEC’s push for expanded clearing in the Treasury market is partly motivated by this desire to increase dealer capacity and improve market resilience.

How Does Central Clearing Reshape Liquidity Provision?

Central clearing fundamentally reshapes the incentives and costs for liquidity providers. The requirement to post margin on inventory increases the carrying cost for market makers. This can lead to a reduction in the depth of the order book, as market makers become more selective about the liquidity they provide.

However, the reduction in counterparty risk can also attract new liquidity providers to the market, potentially increasing competition and offsetting the impact of higher costs. The net effect on liquidity is an empirical question and can vary depending on the specific market and the design of the clearing system.

The table below outlines the strategic trade-offs a firm must consider when operating in a centrally cleared environment.

| Cost Component | Strategic Consideration | Optimization Tactic |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Margin | The opportunity cost of encumbered capital is a primary driver of overall trading cost. High margin requirements can make certain strategies prohibitively expensive. | Employ portfolio margining to net exposures. Utilize collateral optimization services to fund margin with the most cost-effective assets. |

| Bid-Ask Spread | Increased costs for market makers due to margin requirements can lead to wider spreads. This is an implicit cost that impacts all liquidity takers. | Use sophisticated execution algorithms that are sensitive to order book depth and spread dynamics. Time trades to coincide with periods of high liquidity. |

| Balance Sheet Capacity | For regulated entities, the netting benefits of clearing can significantly reduce regulatory capital consumption, freeing up balance sheet for other activities. | Prioritize cleared products for trades that have a high balance sheet impact in the bilateral market. Quantify the value of freed-up capacity. |

| Operational Overhead | Managing collateral, meeting margin calls, and interfacing with the CCP requires significant investment in technology and personnel. | Automate treasury and collateral management functions. Consider using a GCM to outsource some of the operational burden, while carefully analyzing the associated fees. |

The Competitive Landscape and Access Models

The choice of how to access the CCP is a critical strategic decision. The two primary models are direct clearing membership and client clearing via a GCM. Direct membership offers the lowest per-transaction clearing fees and the greatest control, but it comes with the high fixed costs of meeting the CCP’s capital requirements, contributing to the default fund, and building the necessary operational infrastructure. Client clearing involves paying a GCM to clear trades on one’s behalf.

This model has lower fixed costs but higher variable costs in the form of clearing fees charged by the GCM. It also introduces a new form of concentrated risk ▴ dependency on the GCM.

The strategic choice depends on a firm’s trading volume, operational capacity, and risk tolerance. High-volume trading firms may find direct membership to be more cost-effective in the long run. Smaller firms or those with less sophisticated operations will likely find client clearing to be the only viable option.

The increasing mandate for clearing in markets like US Treasuries is forcing many firms to make this strategic choice, weighing the costs and benefits of each model. The potential for multiple competing CCPs further complicates this decision, as firms may need to connect to multiple clearinghouses to access the full range of market liquidity, potentially fragmenting their positions and reducing netting benefits.

Execution

The execution of a trade in a centrally cleared CLOB environment is a complex, multi-stage process that requires precise operational and technological integration. From a systems architecture perspective, the simple act of matching a buy and sell order on the CLOB is merely the prelude to a sophisticated post-trade lifecycle managed by the CCP. Mastering this lifecycle is essential for any firm seeking to control costs and manage risk effectively. The core of this process revolves around novation, margin calculation, and default management.

The Operational Playbook for a Cleared Trade

The lifecycle of a cleared trade can be broken down into a series of distinct operational steps. Each step requires specific technological capabilities and procedural discipline.

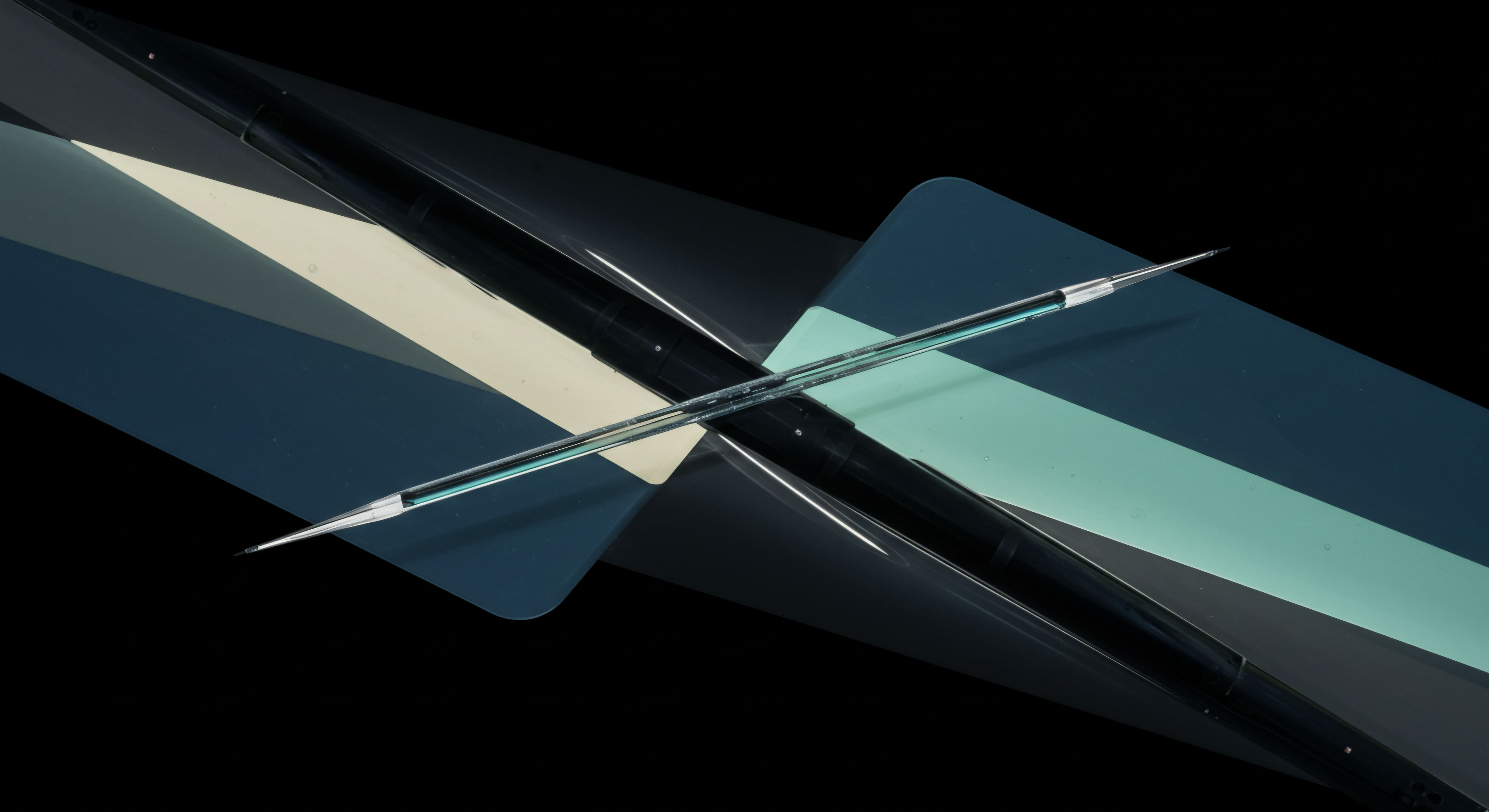

- Trade Execution and Submission ▴ A trade is executed on the CLOB when a buy and sell order match. The trade details are then immediately transmitted from the trading venue to the CCP. This communication typically occurs via a high-speed messaging protocol like FIX (Financial Information eXchange).

- Trade Registration and Novation ▴ The CCP validates the trade details and, if both parties are clearing members in good standing, accepts the trade for clearing. At this moment, novation occurs. The original bilateral contract is legally extinguished and replaced by two new contracts with the CCP. The CCP is now the central counterparty to the trade.

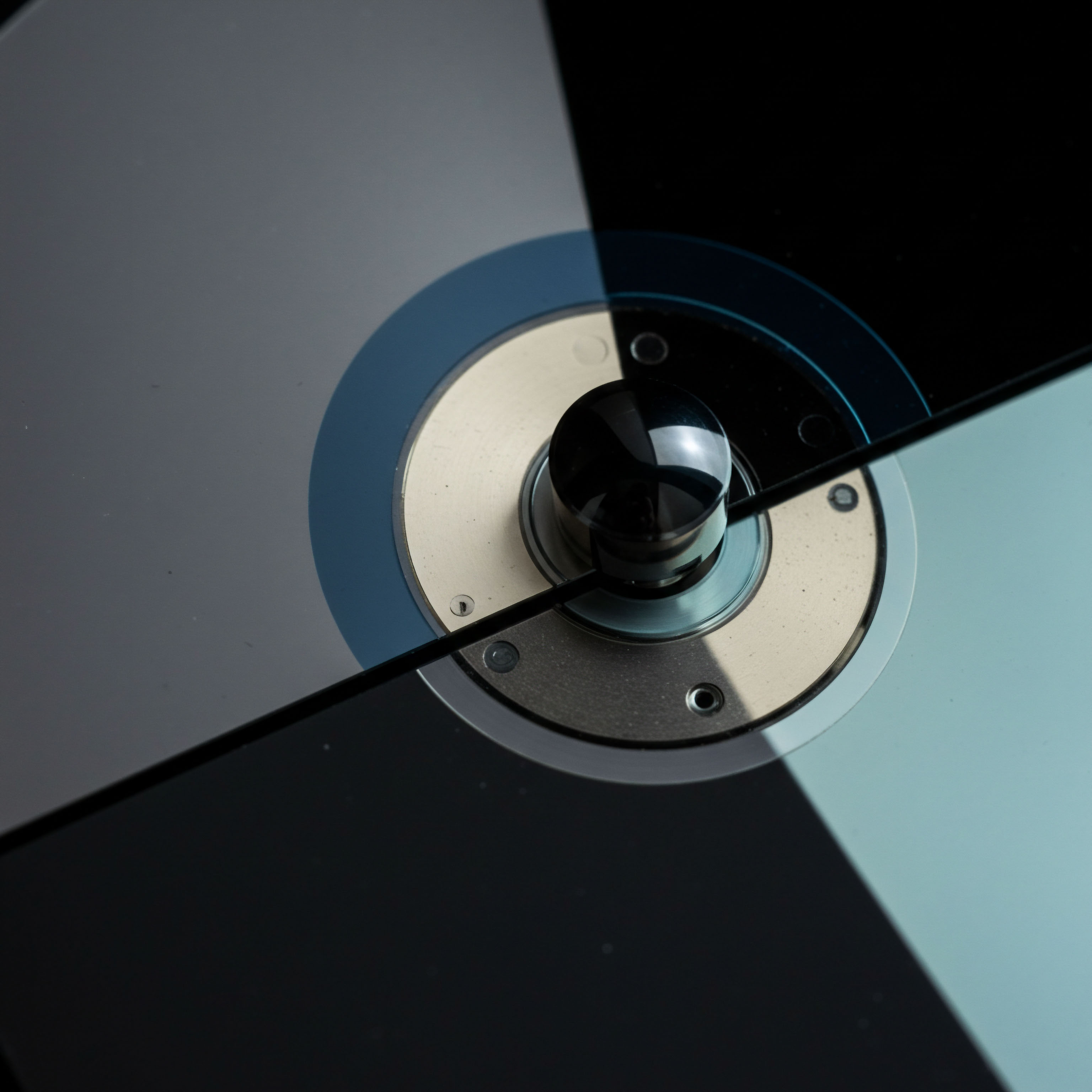

- Real-Time Risk Assessment ▴ Upon novation, the CCP’s risk engine immediately calculates the initial margin (IM) requirement for the new position. This calculation is performed on the clearing member’s entire portfolio to account for netting benefits. The CCP’s system must be capable of performing these complex calculations in near real-time.

- Collateral Management ▴ The clearing member must ensure that it has sufficient collateral on deposit with the CCP to cover the new IM requirement. This requires a sophisticated treasury function that can monitor margin requirements in real-time and move collateral as needed. Collateral is typically held in a segregated account at the CCP.

- Position Maintenance and Margining ▴ For the life of the position, the CCP will mark it to market at least once a day, and often more frequently. This process generates a variation margin (VM) call for members with losing positions. VM payments are typically made in cash and must be settled within a strict timeframe.

- Settlement ▴ At the maturity of the contract (or upon closing out the position), the CCP manages the final settlement process, ensuring the delivery of the underlying asset (if applicable) and the final exchange of cash.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

The cost of clearing is dominated by the cost of funding initial margin. Therefore, understanding and forecasting IM requirements is a critical execution capability. CCPs use various models to calculate IM, with VaR-based models becoming increasingly common. A simplified VaR model for a single position might look something like this:

IM = Position Value Volatility Confidence Level sqrt(Time Horizon)

Where:

- Position Value ▴ The notional value of the trade.

- Volatility ▴ The expected volatility of the instrument’s price over the time horizon.

- Confidence Level ▴ The statistical confidence level for the VaR calculation (e.g. 99% or 99.5%).

- Time Horizon ▴ The expected time to close out a defaulting member’s portfolio (e.g. 2 or 5 days).

The table below provides a hypothetical example of an IM calculation for two different products, illustrating the impact of volatility on margin requirements.

| Product | Position Value | Annualized Volatility | Time Horizon (Days) | 99% Confidence Level (Z-score) | Calculated Initial Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Treasury Bond Future | $10,000,000 | 5% | 2 | 2.33 | $10,000,000 0.05 2.33 sqrt(2/252) = $103,500 |

| Equity Index Future | $10,000,000 | 20% | 2 | 2.33 | $10,000,000 0.20 2.33 sqrt(2/252) = $414,000 |

This simplified example demonstrates how higher volatility leads to significantly higher margin requirements. A firm’s execution strategy must incorporate sophisticated margin modeling to predict these costs and optimize capital usage. This involves not only calculating IM for individual positions but also understanding the portfolio effects that can reduce overall margin through netting.

What Happens in a Member Default?

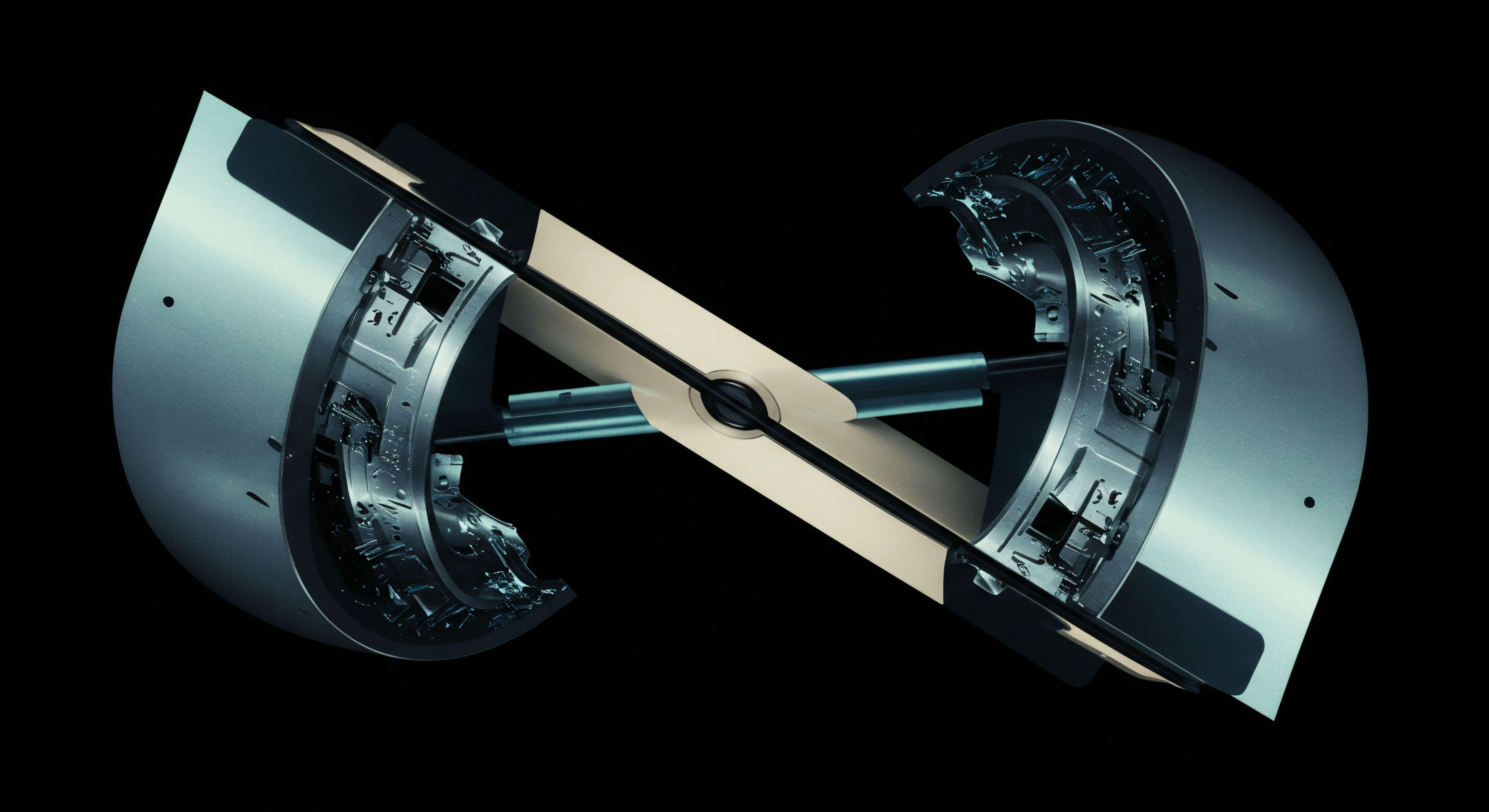

The ultimate test of a CCP’s execution framework is its ability to manage a member default. The process is governed by a strict, pre-defined set of rules known as the default waterfall. This waterfall ensures that losses are contained and that the broader market is protected.

The default waterfall typically proceeds as follows:

- The Defaulting Member’s Resources ▴ The CCP first seizes and liquidates the defaulting member’s initial margin and its contribution to the default fund.

- The CCP’s Own Capital ▴ The CCP then contributes a portion of its own capital (often called “skin-in-the-game”) to cover any remaining losses. This aligns the CCP’s incentives with those of its members.

- The Non-Defaulting Members’ Default Fund Contributions ▴ If losses still remain, the CCP will draw on the default fund contributions of the non-defaulting members.

- Further Loss Allocation ▴ In the extreme event that the default fund is exhausted, the CCP may have the right to call for additional assessments from its members or use other loss allocation tools.

This structured process is designed to prevent the contagion that can occur in bilateral markets. For a trading firm, the execution implications are clear ▴ the choice of a CCP and the analysis of its default waterfall are critical components of counterparty risk management. A firm must understand its potential exposure in a default scenario and factor that into its overall risk assessment.

System Integration and Technological Architecture

Executing trades in a cleared environment requires a robust and integrated technology stack. The key components include:

- Order and Execution Management Systems (OMS/EMS) ▴ These systems must be able to route orders to the CLOB and receive execution confirmations. They must also be able to tag trades with the correct clearing information.

- Post-Trade Processing Systems ▴ These systems are responsible for communicating with the CCP, submitting trades for clearing, and receiving margin calls. They must be able to process FIX messages and other CCP-specific protocols.

- Collateral Management Systems ▴ These are specialized systems that track a firm’s collateral inventory, optimize its usage, and manage the process of pledging and receiving collateral from the CCP.

- Risk Management Systems ▴ These systems must be able to replicate the CCP’s margin models to allow the firm to forecast its margin requirements and manage its risk exposure in real-time.

The integration of these systems is a significant undertaking. Firms must invest in technology and personnel to build and maintain this infrastructure. The move towards mandatory clearing in various markets is a major driver of this investment, as firms that fail to adapt will be unable to access liquidity in these markets. The operational challenge is particularly acute for smaller firms, who may need to rely on third-party vendors or GCMs to provide some of these capabilities.

References

- International Monetary Fund. (2024). Expanding central clearing in Treasury Markets (2). IMF Connect.

- Charoenwong, B. Kwan, A. & Wu, Y. (2022). Does Central Clearing Affect Price Stability? Evidence from Nordic Equity Markets. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- The TRADE. (2024). A look into the centrally cleared future. The TRADE.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2024). Developments in Central Clearing in the U.S. Treasury Market.

- International Monetary Fund. (2022). Expanding central clearing in US Treasury Markets ▴ Benefits and Costs. IMF Connect.

Reflection

The transition to a centrally cleared trading architecture is more than a procedural adjustment; it is a systemic evolution. The knowledge of its cost structure and operational mechanics provides a powerful lens through which to re-evaluate your own firm’s operational framework. Consider the flow of information and capital within your organization. Is your treasury function fully integrated with your trading desk, capable of responding to intraday margin calls with precision and efficiency?

Is your risk modeling sophisticated enough to predict and optimize collateral costs before trades are even executed? The answers to these questions reveal the true resilience and efficiency of your operating system. The centrally cleared market does not simply present a new set of costs; it offers a new paradigm for risk management and capital efficiency. The ultimate advantage lies not in simply paying the price of clearing, but in building an internal system that masters its complexities and harnesses its benefits.

Glossary

Counterparty Risk

Central Clearing

Novation

Variation Margin

Bid-Ask Spread

Margin Requirements

Opportunity Cost

Default Fund Contributions

Clearing Fees

Market Makers

Risk Management

General Clearing Member

Client Clearing

Direct Costs

Centrally Cleared

Clob

Initial Margin

Default Fund

Balance Sheet

Market Liquidity

Collateral Management