Concept

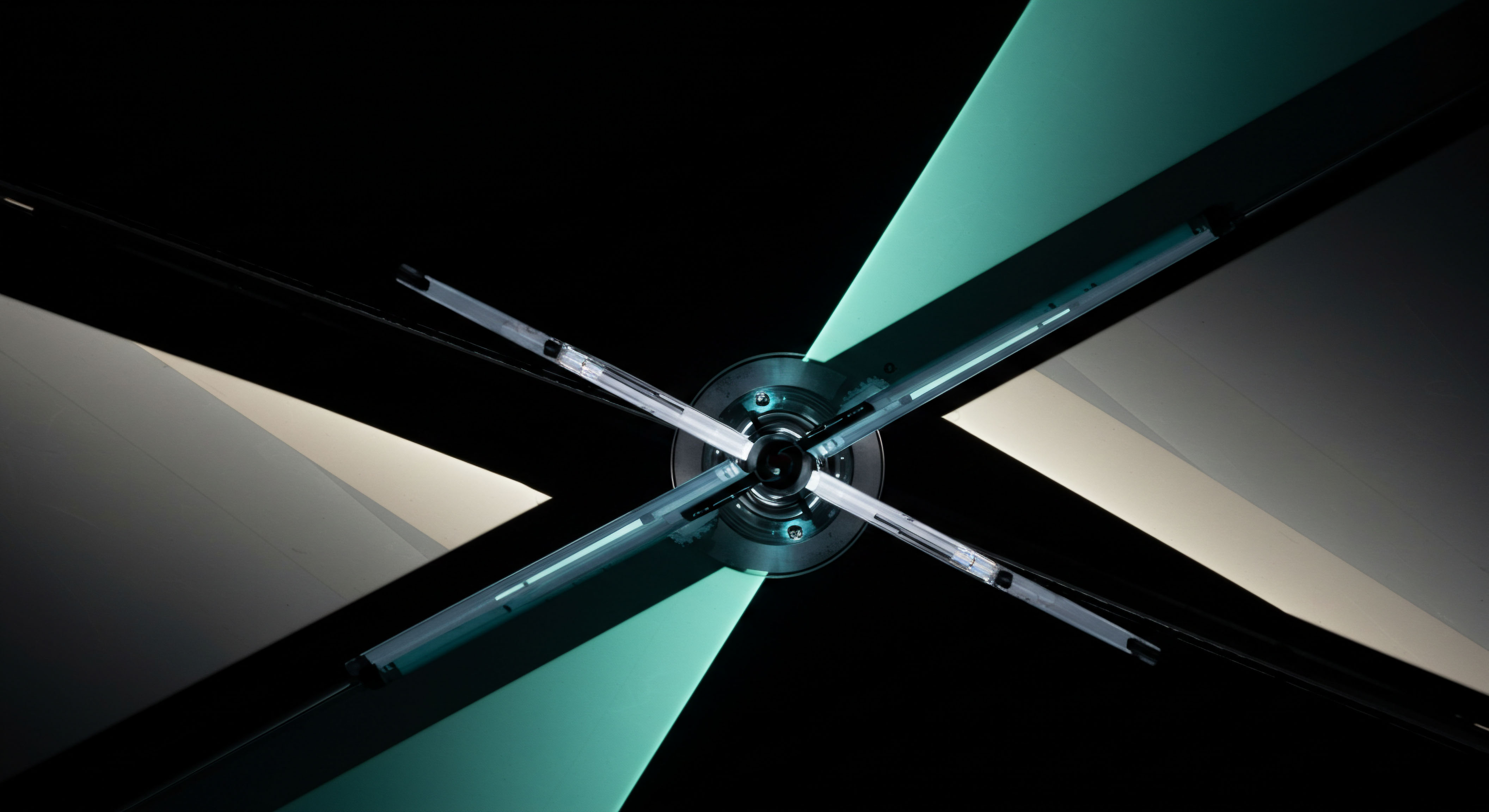

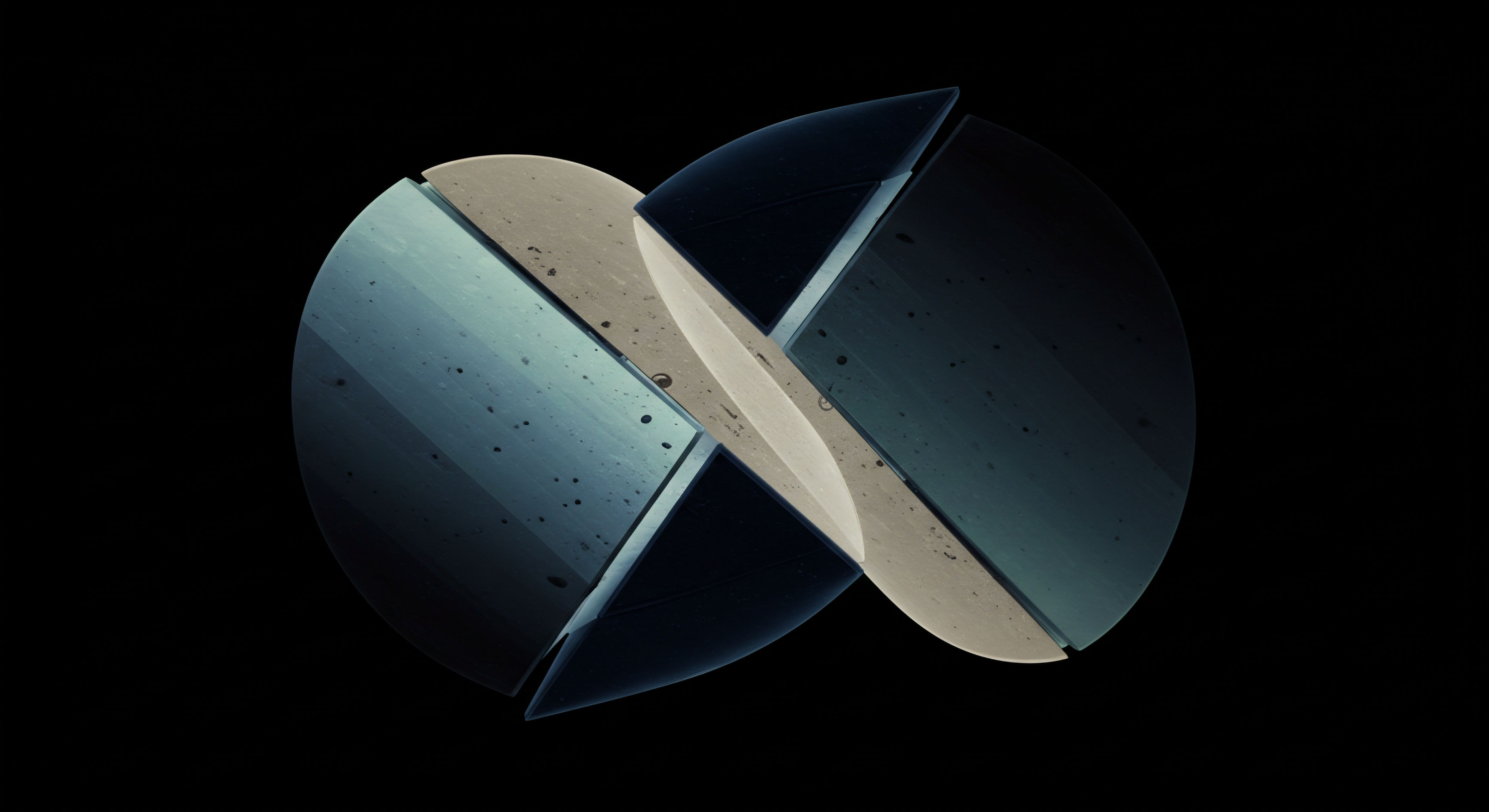

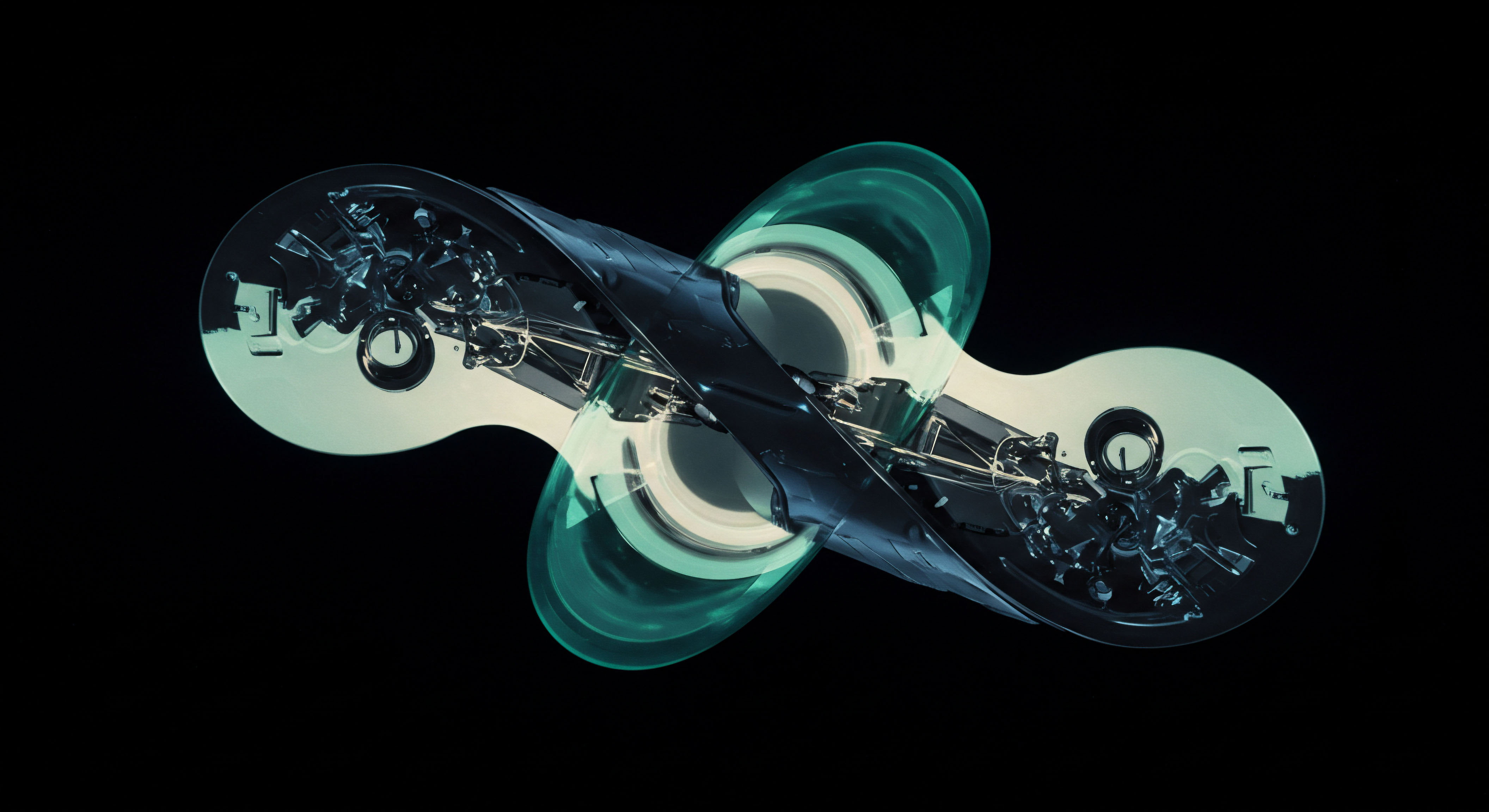

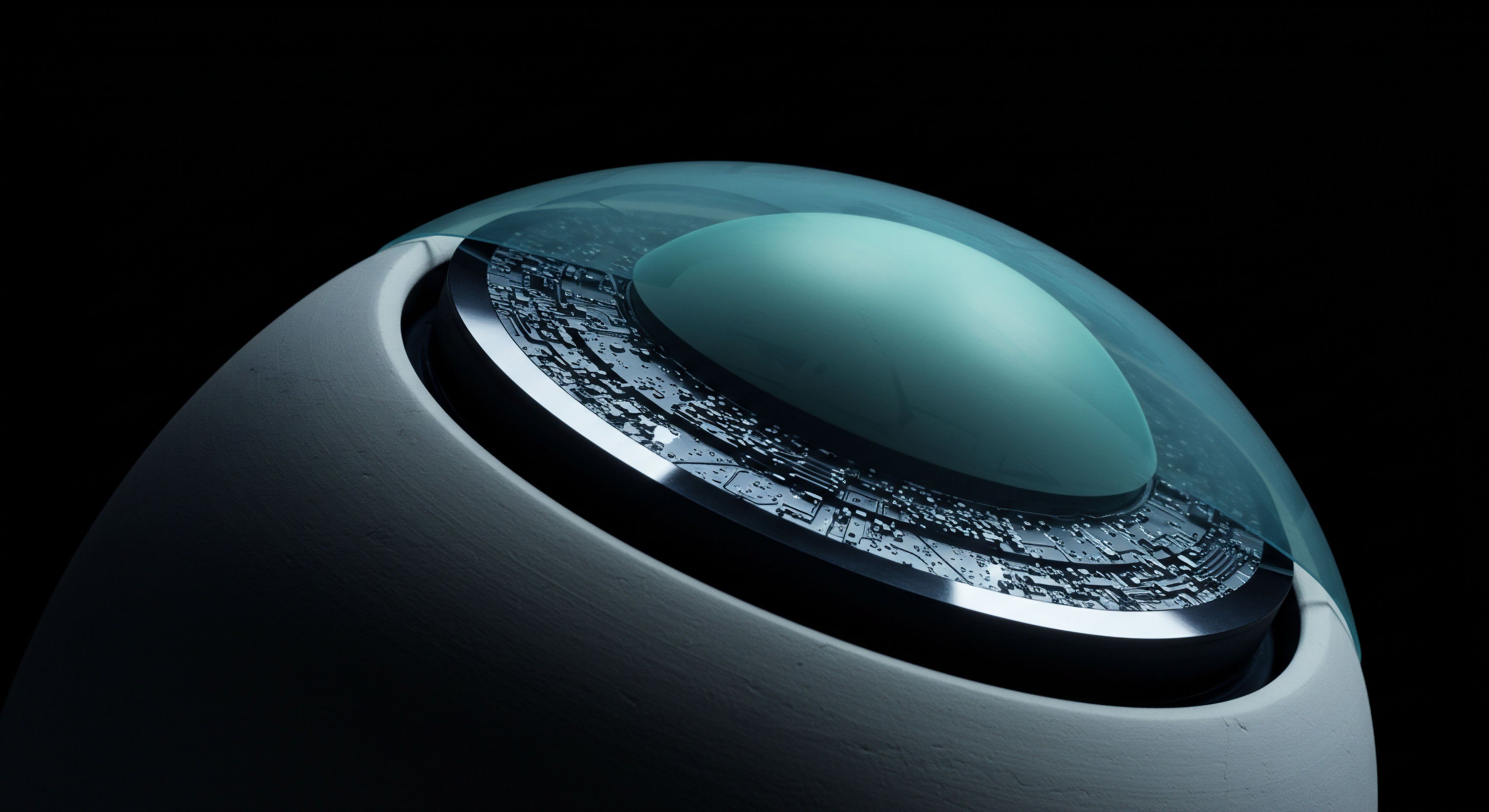

The core function of a Central Counterparty (CCP) is to become the operational nexus of a market, absorbing and reallocating counterparty risk through a process of novation. By stepping between the original buyer and seller, the CCP transforms a complex web of bilateral obligations into a simplified hub-and-spoke architecture. Within this centralized structure, the mechanism of multilateral netting materializes. This process aggregates a clearing member’s multitude of positions across all its counterparties into a single net position with the CCP.

The result is a dramatic reduction in the total gross exposure and, consequently, a profound decrease in the capital required for initial margin. It is a system designed for maximum capital efficiency.

Clearing fragmentation directly dismantles this elegant architecture. Fragmentation occurs when identical or economically equivalent contracts are cleared across multiple, non-interoperable CCPs. Instead of a single, unified pool of positions that can be netted against one another, a firm is left with multiple, isolated pools. A long position in an interest rate swap at one CCP can no longer offset a short position in an identical swap at another.

Each position must be margined independently at its respective clearinghouse. The foundational benefit of multilateral netting ▴ the ability to compress gross exposures down to a single net obligation ▴ is systematically negated. The system reverts to a state of balkanized risk, where capital efficiency is eroded by the operational boundaries of competing clearing infrastructures.

Clearing fragmentation forces a dealer to collateralize offsetting positions at different CCPs, negating netting benefits and increasing costs.

This erosion is not a theoretical abstraction. It manifests as a tangible increase in the total initial margin a firm must post. Capital that could be deployed for investment, hedging, or market-making activities is instead sequestered as collateral, tied up in redundant margin calls across disparate venues. The operational load also intensifies.

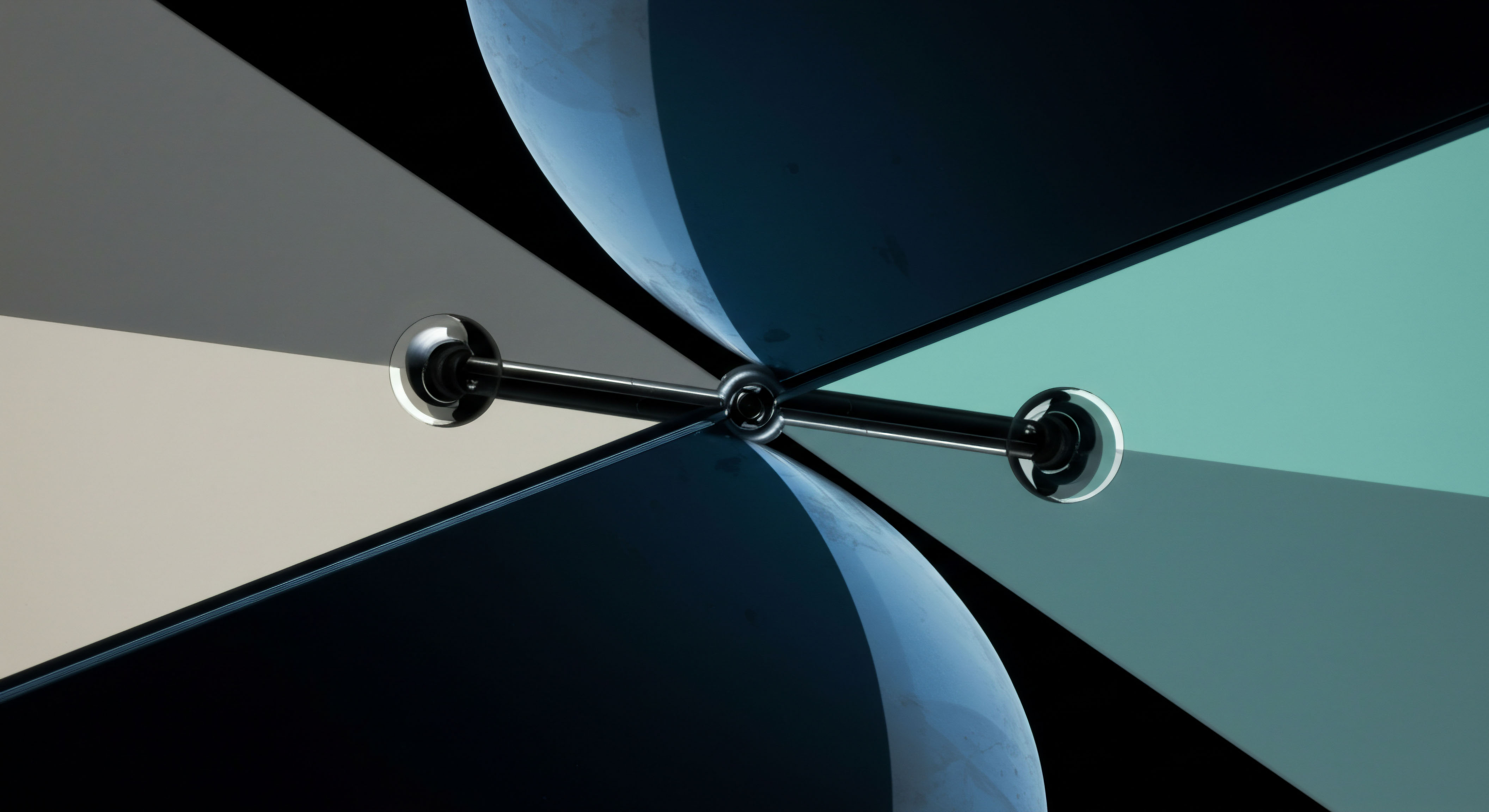

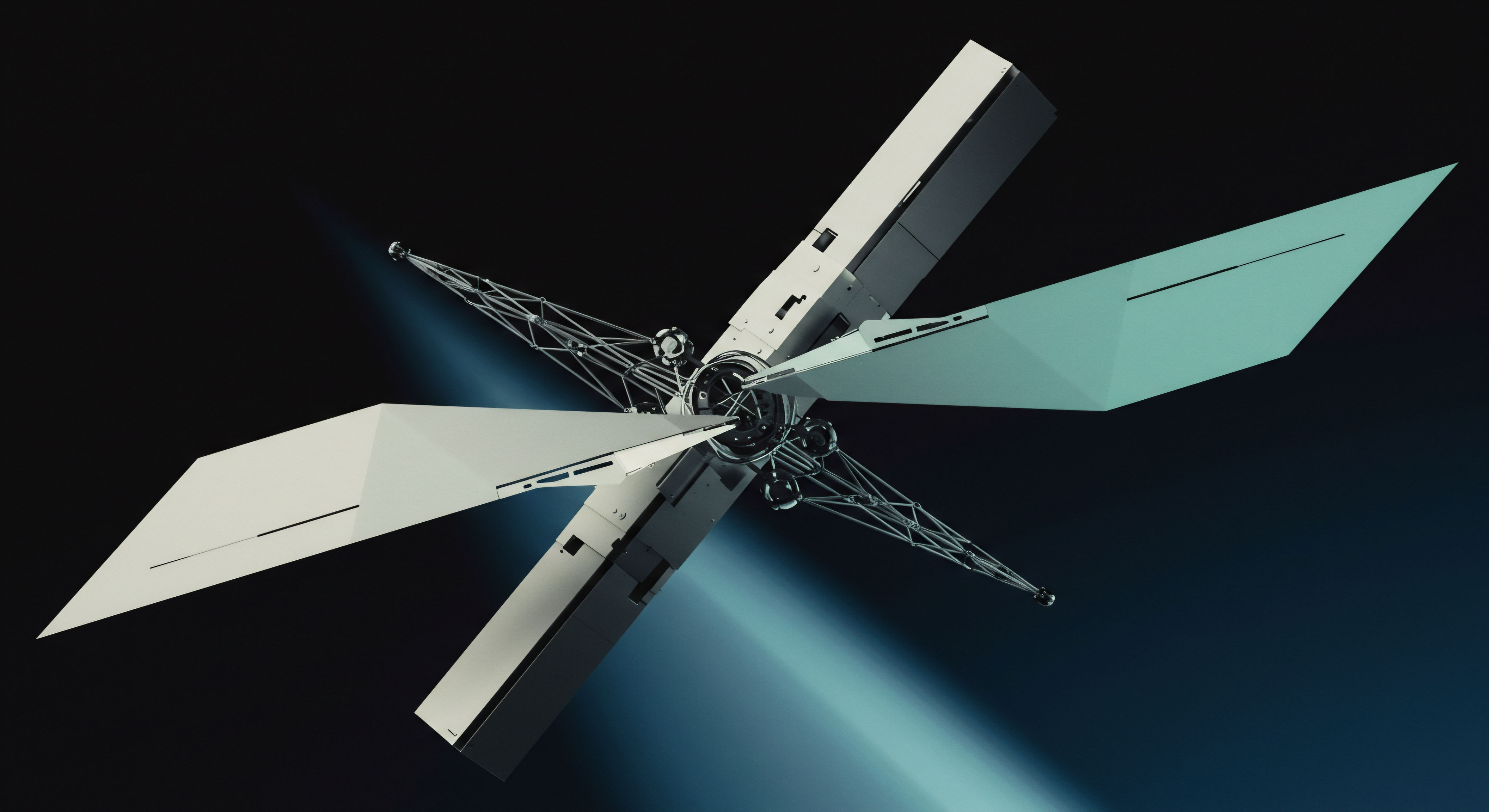

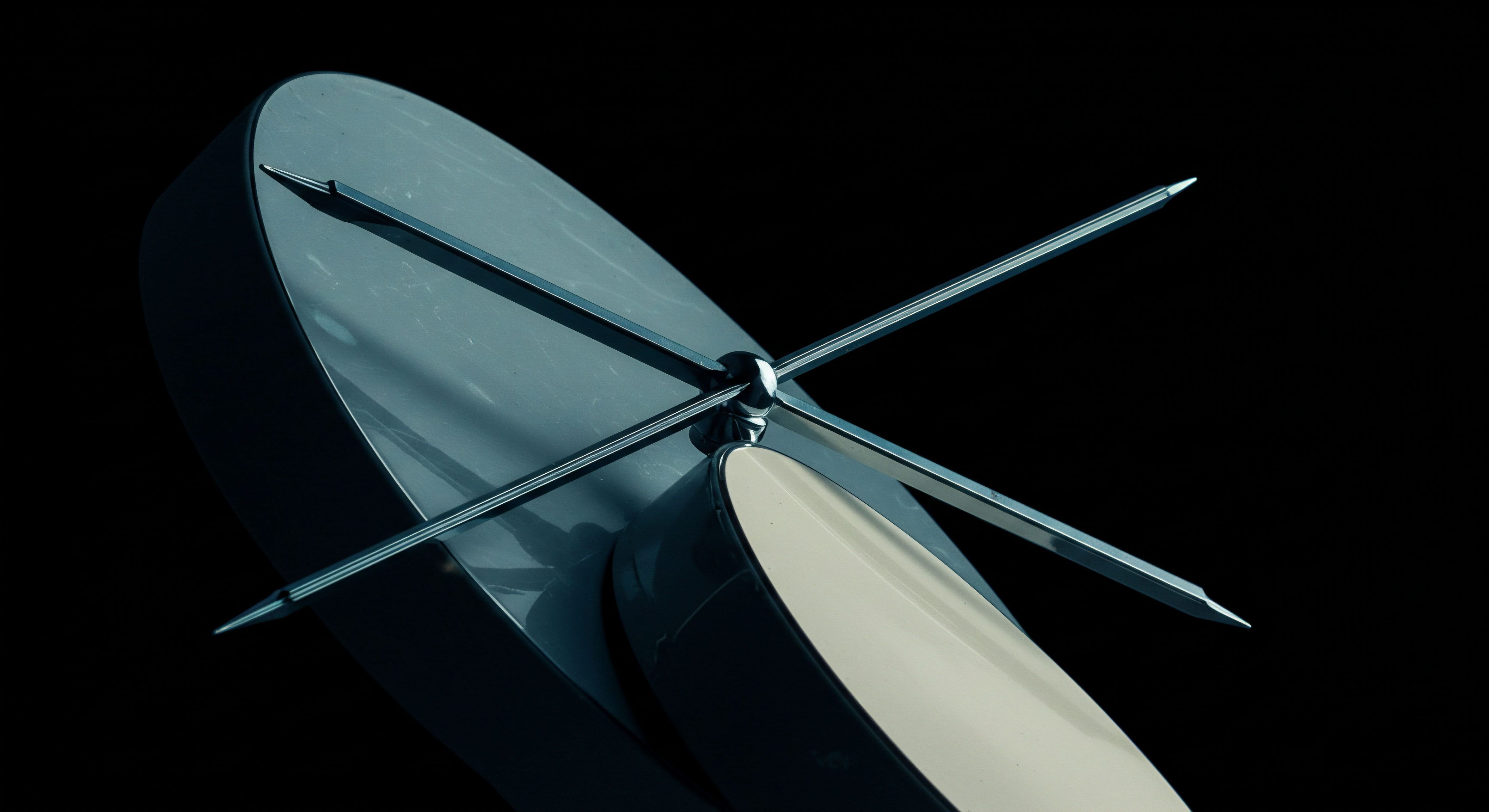

A firm must now manage liquidity, collateral, and risk not for one centralized entity, but for a collection of them, each with its own rulebook, margin methodology, and operational quirks. The simplicity of the hub-and-spoke model is lost, replaced by the complexity of managing multiple, disconnected clearing relationships. This structural inefficiency introduces new forms of systemic friction, most notably the “CCP basis,” a persistent price differential for the same product cleared at different CCPs, which reflects the embedded cost of fragmented clearing.

Strategy

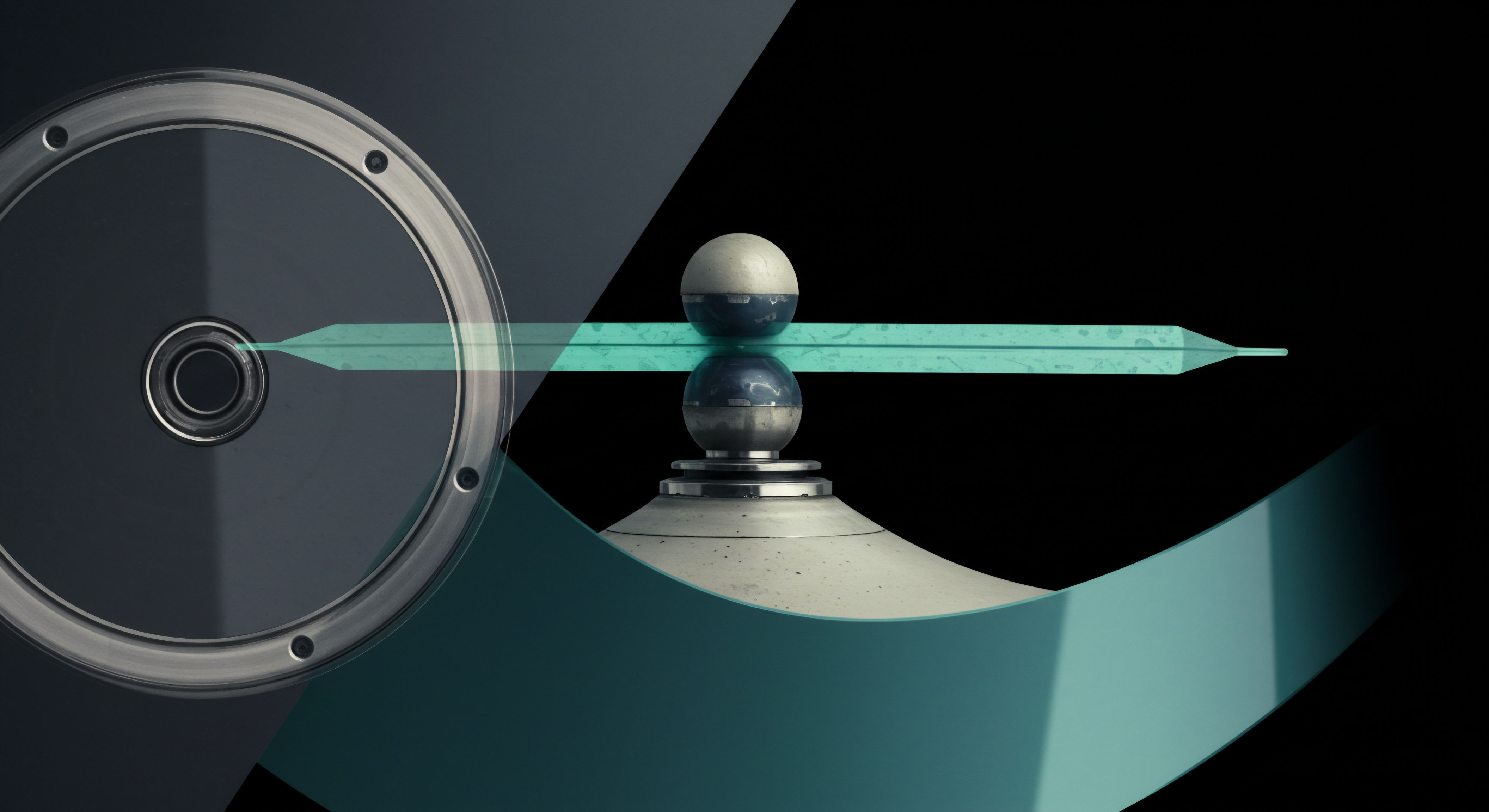

The strategic implications of clearing fragmentation extend far beyond a simple increase in margin costs. They fundamentally alter a firm’s approach to liquidity management, risk modeling, and market access. In a unified clearing environment, a firm’s treasury function operates with a high degree of predictability. In a fragmented world, it must become a dynamic, multi-faceted operation, constantly monitoring and managing liquidity across several collateral pools.

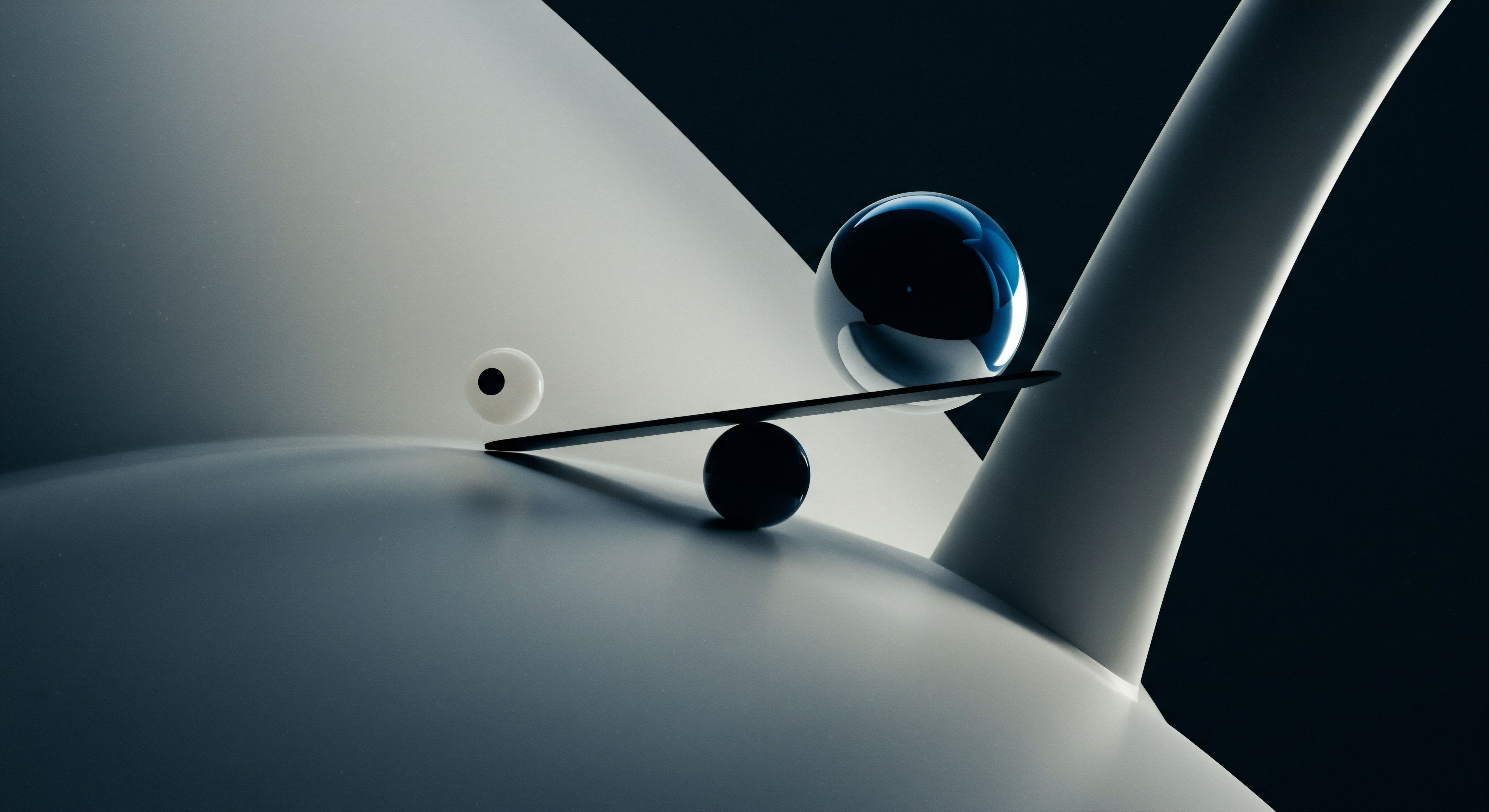

The primary strategic challenge is the structural inability to achieve a true, risk-neutral flat position from a clearing perspective. A dealer might have a perfectly balanced book on a global economic basis, yet from the perspective of the individual CCPs, it holds significant, non-zero positions that demand collateral.

How Does Fragmentation Impact a Firm’s Liquidity Management Strategy?

A firm’s liquidity management strategy must evolve from a centralized model to a decentralized, operationally intensive one. The need to post margin at multiple CCPs for what are economically offsetting positions creates a significant drain on high-quality liquid assets (HQLA). This has several downstream consequences:

- Collateral Silos ▴ Each CCP acts as a silo for collateral. Assets posted to one clearinghouse cannot be used to satisfy a margin call at another. This prevents the efficient, portfolio-wide use of a firm’s available collateral.

- Increased Funding Costs ▴ The higher overall margin requirement necessitates holding larger buffers of HQLA or entering into more frequent and costly repo transactions to source eligible collateral. This directly impacts the firm’s funding costs and profitability.

- Operational Drag ▴ The treasury team must manage multiple collateral accounts, monitor different margin call schedules, and understand varying eligibility criteria for each CCP. This increases operational risk and requires investment in sophisticated treasury management systems.

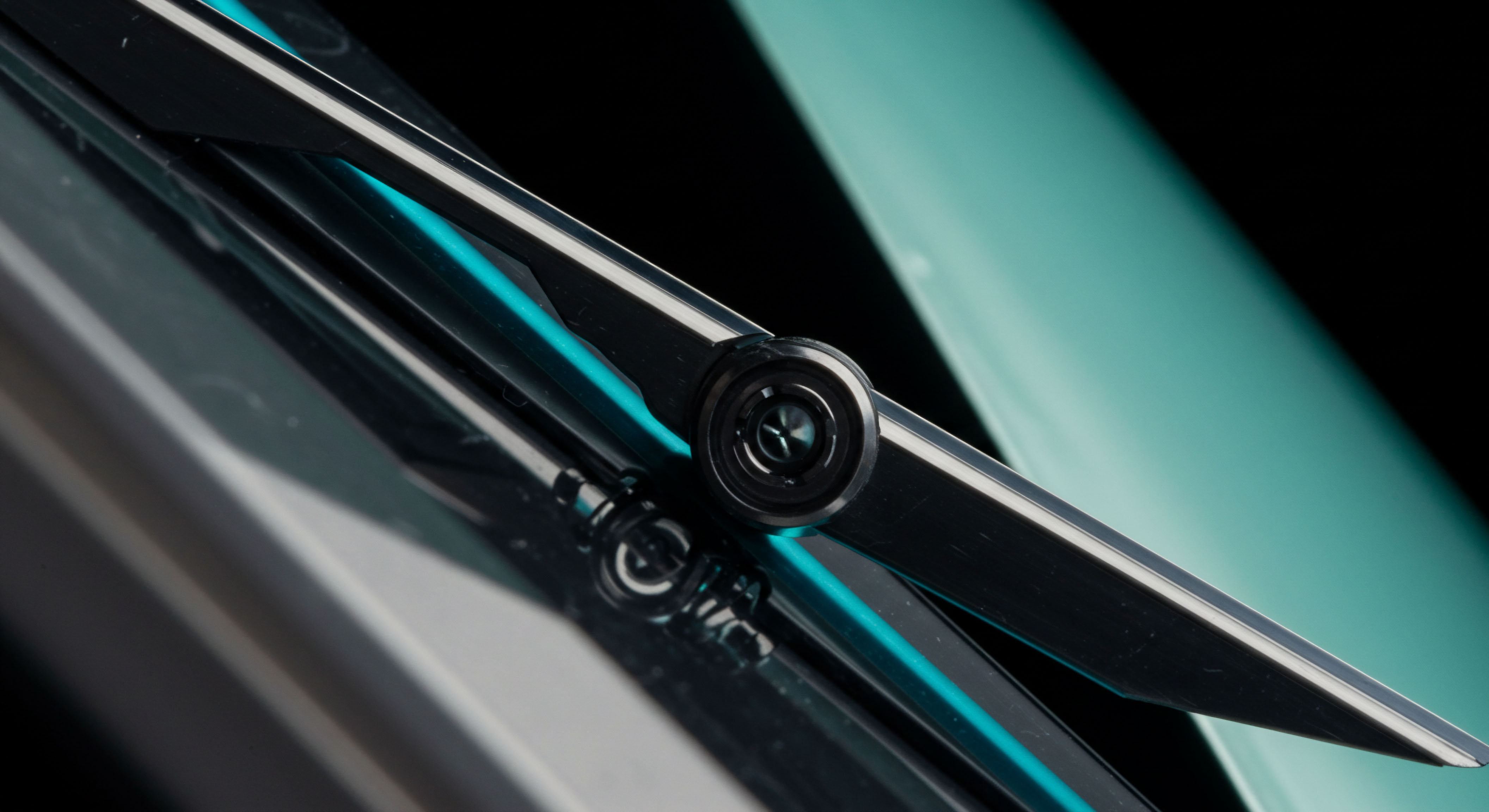

This fragmentation forces a strategic recalculation of the costs of market-making. Dealers who provide liquidity must price the increased collateral costs into their quotes. This leads directly to the CCP basis, where the price for clearing a contract at a CCP with a net seller imbalance will be lower than at a CCP with a net buyer imbalance.

The basis represents the dealer’s cost of carrying the directional inventory at each CCP. For end-users, this means the choice of where to clear a trade has a direct impact on execution price, adding a new layer of complexity to achieving best execution.

The CCP basis arises as dealers pass on the increased collateral costs from fragmented clearing to their clients through price differentials.

Comparative Analysis of Margin Requirements

To illustrate the direct financial impact, consider a simplified comparison of margin requirements for a hypothetical portfolio in both a unified and a fragmented clearing environment. The table below demonstrates how the loss of netting dramatically inflates collateral obligations.

| Scenario | Position at CCP A | Position at CCP B | Net Portfolio Position | Margin at CCP A | Margin at CCP B | Total Initial Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unified Clearing (Single CCP) | +$500M (long), -$450M (short) | N/A | +$50M | $5M (on $50M net) | N/A | $5M |

| Fragmented Clearing | +$500M (long) | -$450M (short) | +$50M | $50M (on $500M gross) | $45M (on $450M gross) | $95M |

In this illustration, fragmentation increases the total initial margin requirement by a factor of 19. While the actual margin calculations are far more complex, involving methodologies like VaR (Value-at-Risk), the principle holds. The inability to net gross positions across clearinghouses leads to a structural magnification of collateral demand. This strategic burden forces firms to re-evaluate which markets to participate in, how to price their services, and the level of operational and technological investment required to simply maintain their footprint.

Execution

At the execution level, clearing fragmentation imposes a significant operational and quantitative burden on financial institutions. The theoretical loss of netting efficiency translates into concrete, daily challenges related to collateral management, risk system integration, and regulatory reporting. Firms must architect their internal systems to navigate a landscape where a single economic risk position is represented by multiple, legally distinct positions across different clearing venues. This requires a granular, robust, and highly automated operational framework.

What Is the Operational Workflow for Managing Fragmented Positions?

The operational workflow for a firm managing positions across fragmented CCPs is substantially more complex than in a unified environment. It involves a continuous, multi-stage process that requires tight integration between trading desks, treasury, risk management, and back-office operations.

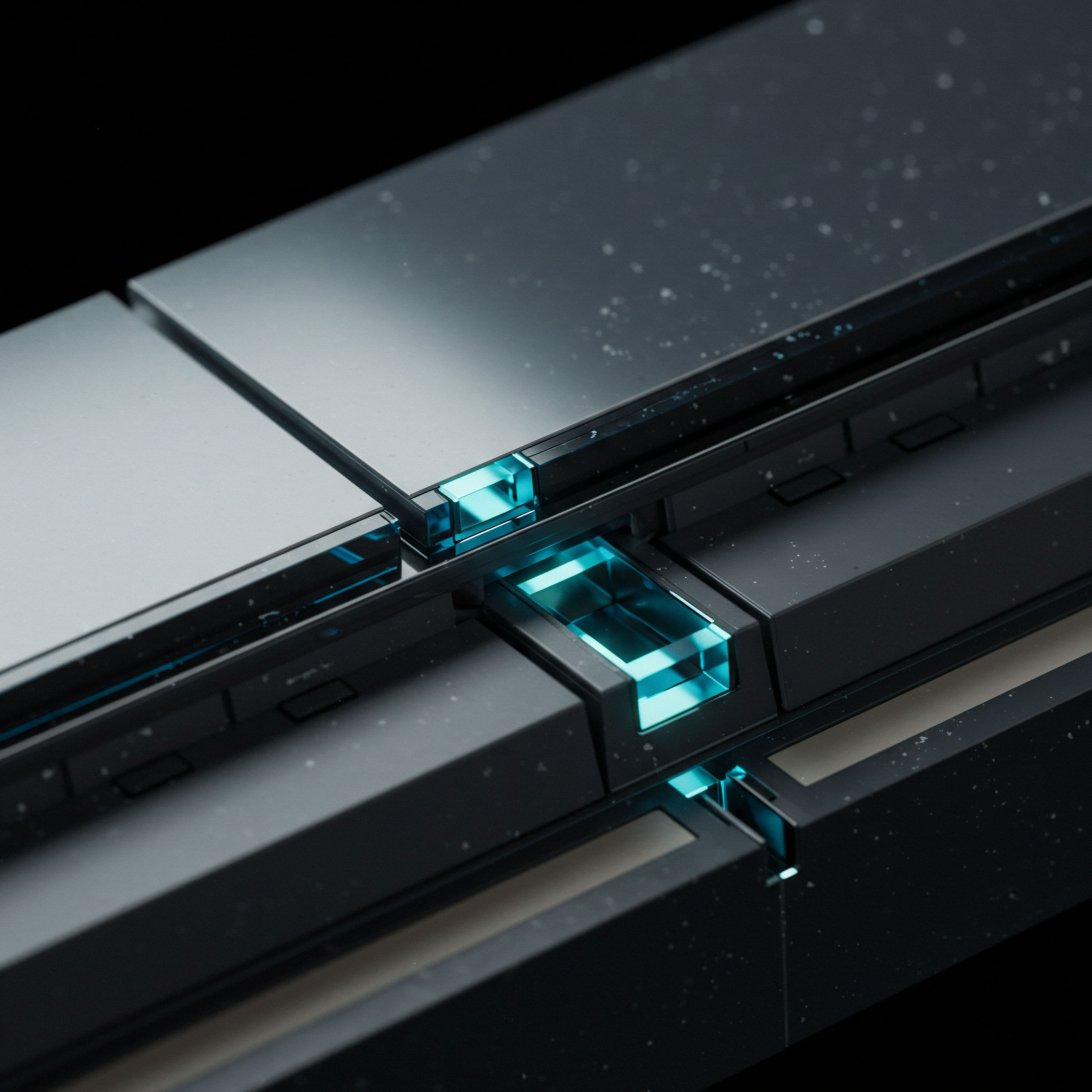

- Trade Execution and Allocation ▴ The process begins at the point of execution. The trading desk must decide not only the price and quantity of a derivative but also the CCP where it will be cleared. This decision is influenced by the CCP basis, client preference, and the firm’s existing positions at each venue.

- Real-Time Position Monitoring ▴ Immediately post-trade, the firm’s risk and collateral systems must be updated. These systems need to maintain separate, real-time ledgers for each CCP, tracking gross positions, variation margin, and initial margin requirements independently.

- Margin Calculation and Forecasting ▴ The firm must run margin calculations for each CCP according to that CCP’s specific methodology (e.g. SPAN, VaR). Sophisticated firms will also run “what-if” scenarios to forecast margin impact before executing large trades.

- Collateral Optimization ▴ A dedicated collateral management function is required. This team must identify which eligible assets (cash, government bonds) to post to which CCP, optimizing for the lowest funding cost while ensuring all margin calls are met. This involves managing multiple collateral accounts and navigating different haircut schedules.

- Reconciliation and Reporting ▴ The back office must perform daily, and often intraday, reconciliations of positions, trades, and collateral balances with each CCP. This is a resource-intensive process prone to breaks that require manual intervention.

Quantitative Impact on Portfolio Margining

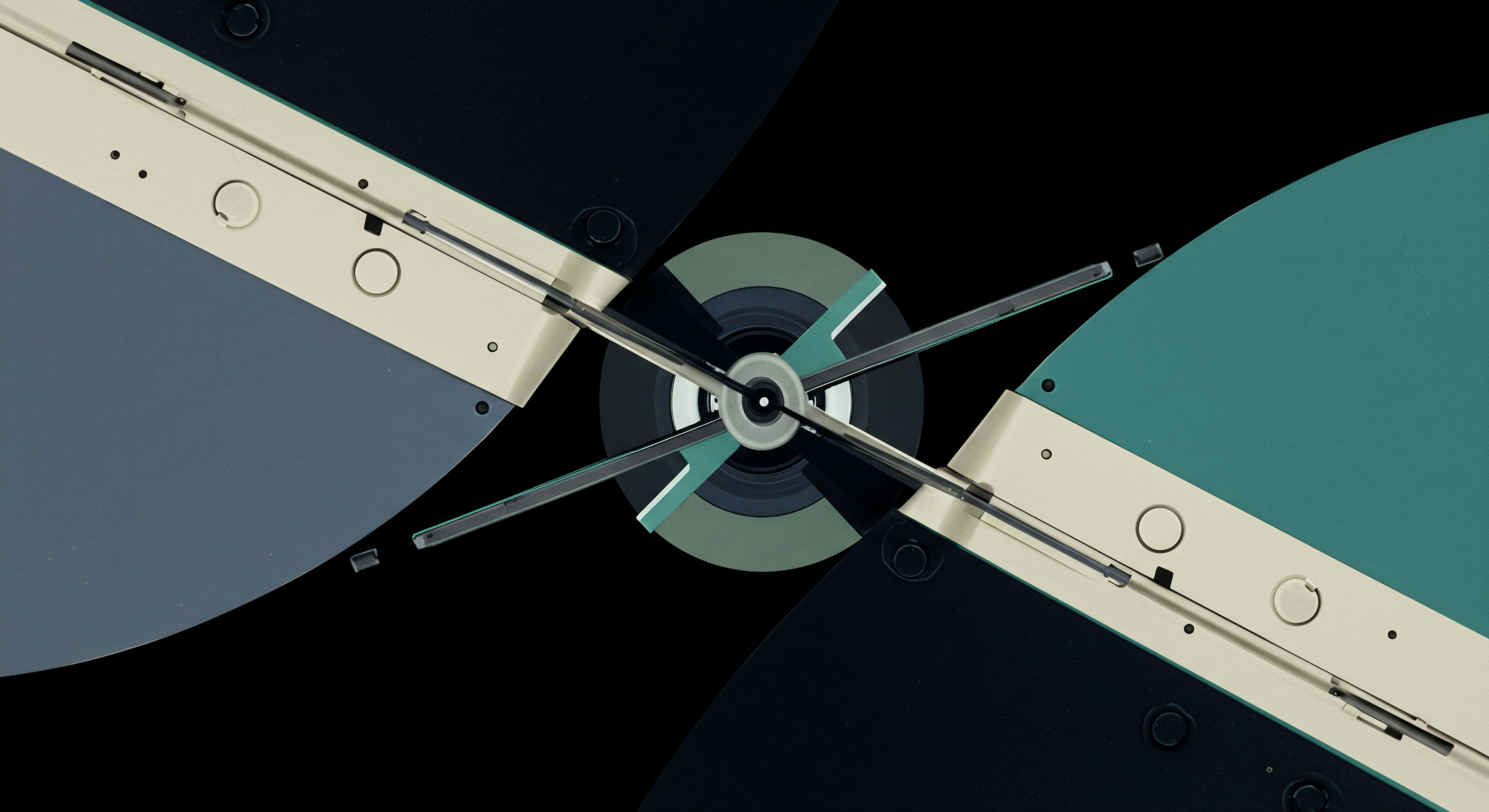

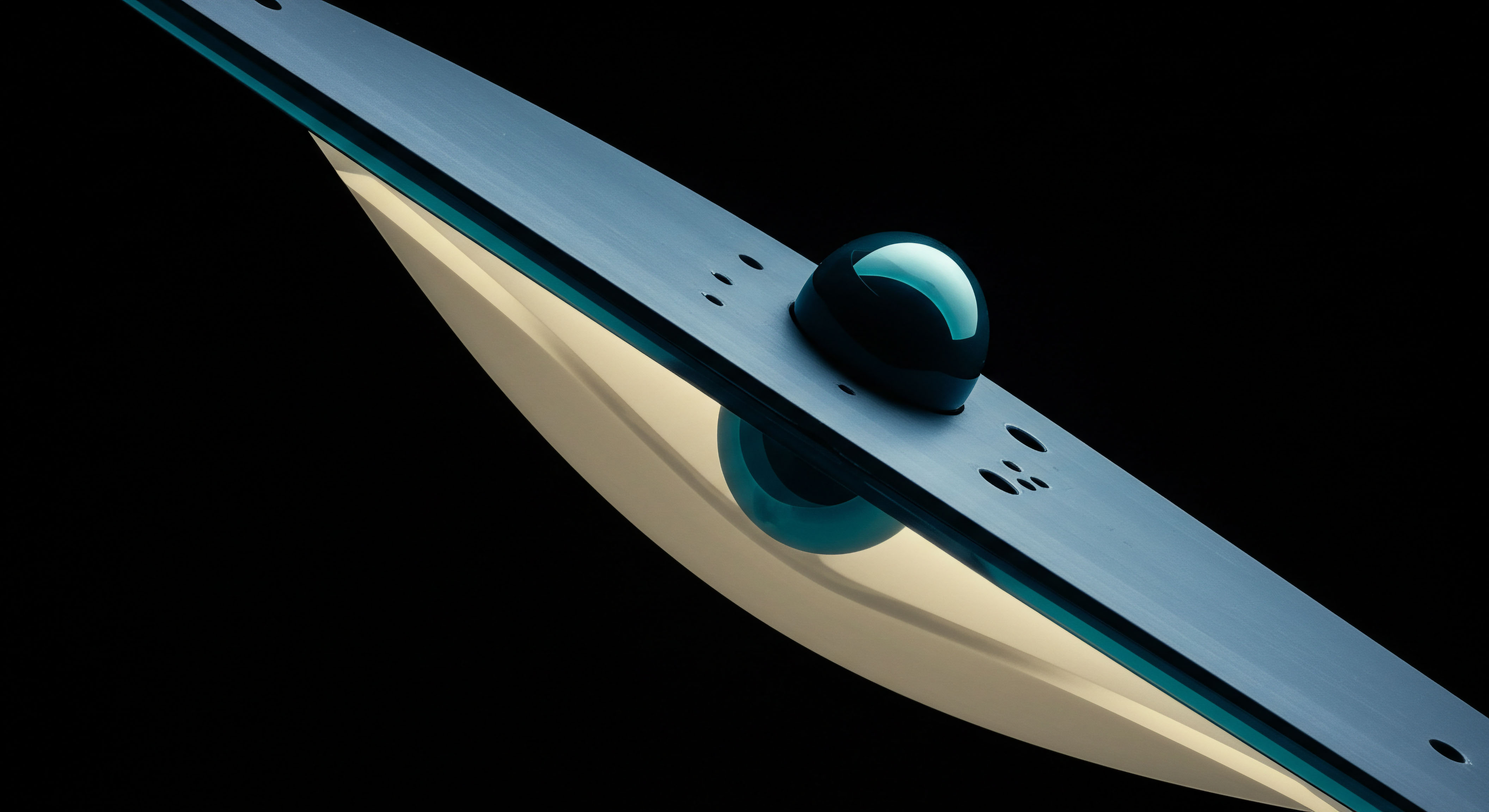

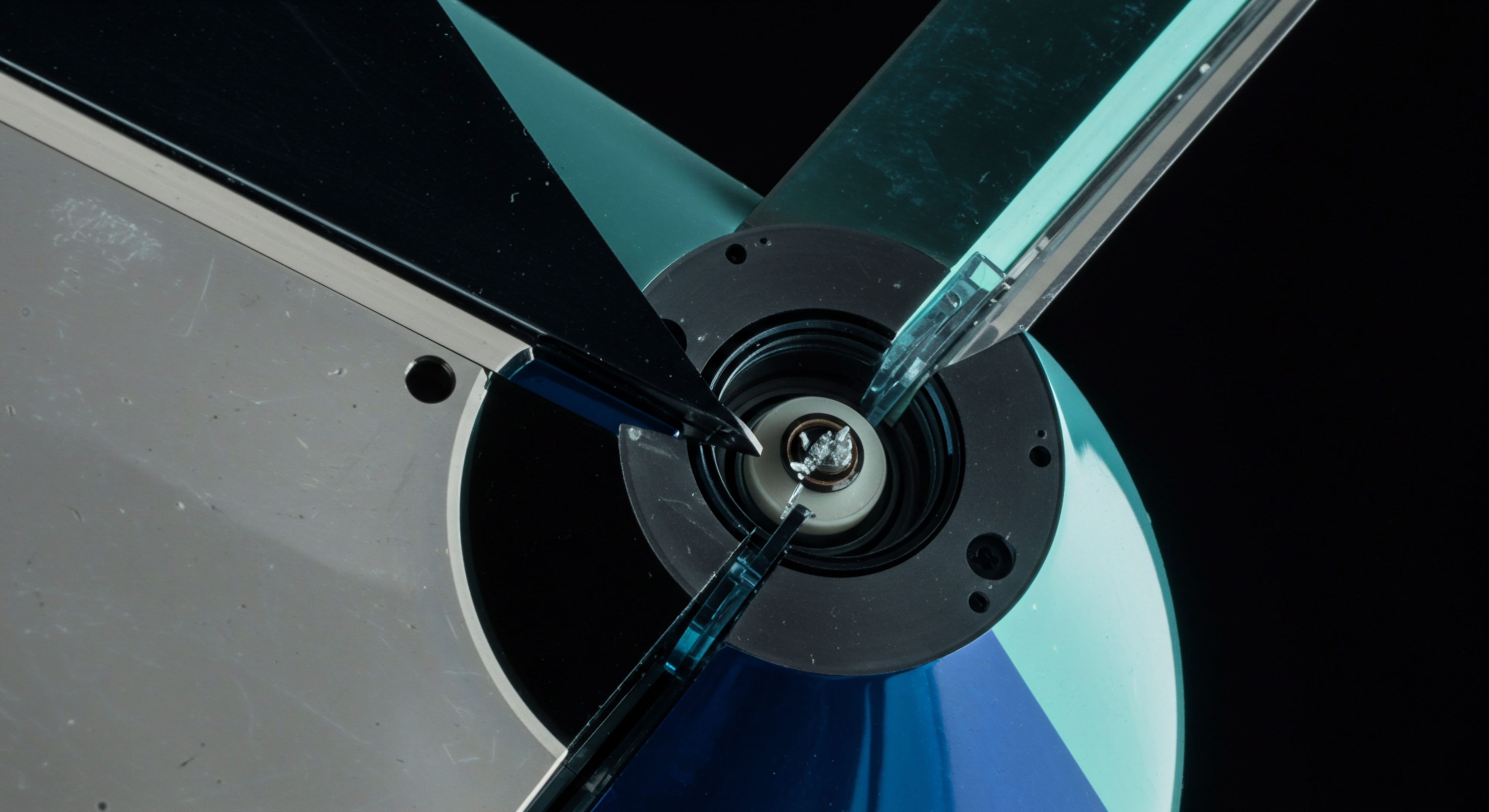

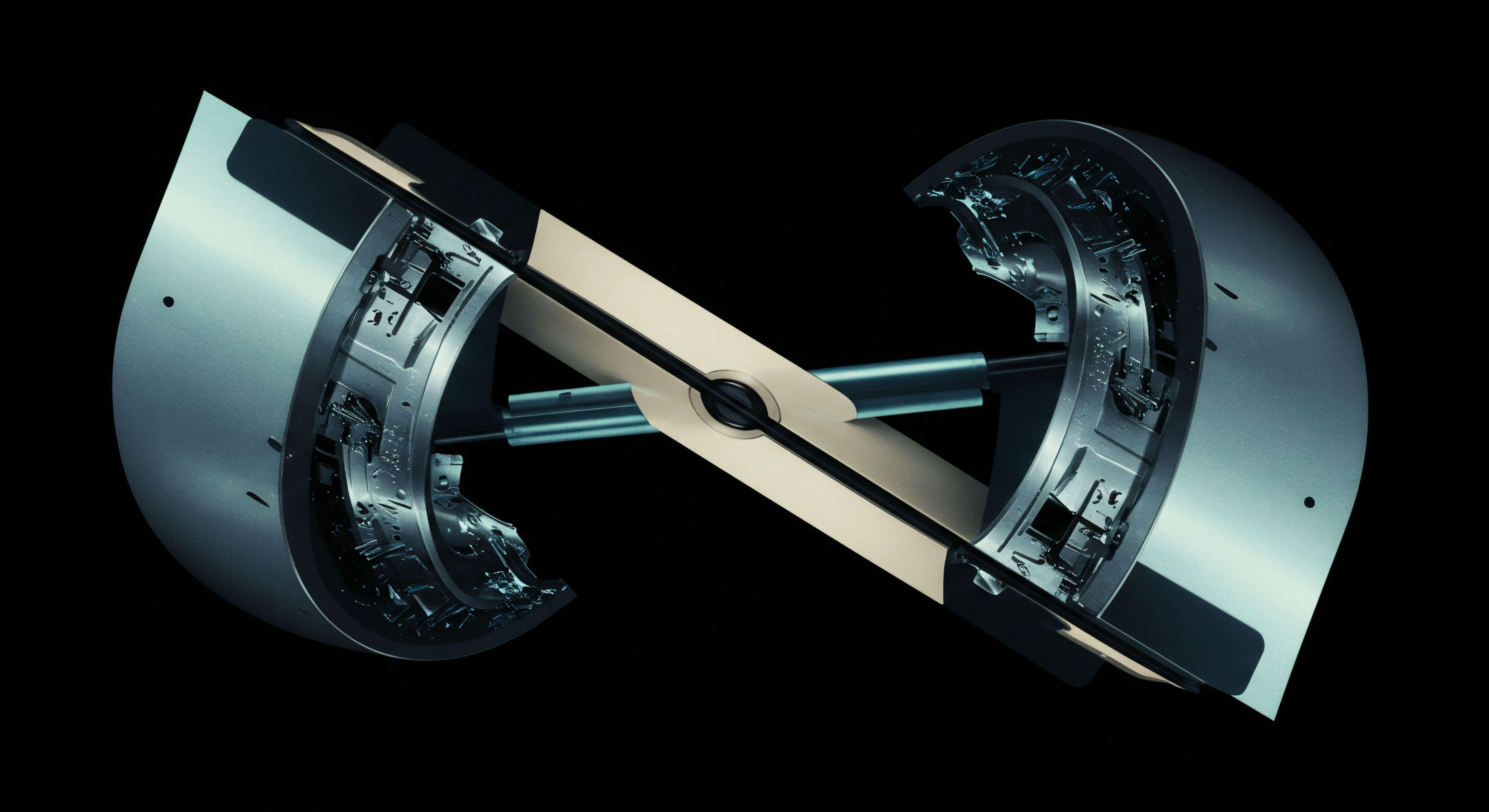

The most direct quantitative impact is the destruction of portfolio margining benefits. Portfolio margining allows a firm to offset the risk of one position with another within the same account, leading to lower overall margin requirements. Fragmentation breaks this.

A long position in a 10-year USD interest rate swap at LCH cannot be risk-offset against a short position in a 10-year USD interest rate swap at CME, even though they are economically identical. The table below provides a more granular illustration of this effect on a hypothetical derivatives portfolio.

| Instrument | Notional Amount | Clearing Venue | Directional Risk Contribution | Stand-Alone Margin (IM) | Portfolio Netted Margin (IM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10Y USD IRS | +$1 Billion | CCP A (LCH) | +$100M DV01 | $80M | $5M (at a single CCP) |

| 10Y USD IRS | -$1 Billion | CCP B (CME) | -$100M DV01 | $80M | |

| 5Y EUR IRS | +$2 Billion | CCP A (LCH) | +$120M DV01 | $100M | $10M (at a single CCP) |

| 5Y EUR IRS | -$1.8 Billion | CCP B (CME) | -$108M DV01 | $90M | |

| Total Fragmented IM | $350M | N/A | |||

| Total Unified IM | N/A | $15M |

To achieve maximum netting benefits, the optimal structure is a single CCP for a given asset class.

The data demonstrates a more than 20-fold increase in capital requirements due to fragmentation. Executing this strategy requires significant investment in technology. Firms need a centralized collateral and liquidity management platform that can interface with multiple CCPs via APIs.

This system must be able to provide a single, consolidated view of all positions and margin requirements, run optimization algorithms for collateral allocation, and automate the settlement and reconciliation processes. Without this technological architecture, the operational risks and funding costs associated with navigating a fragmented clearing landscape become prohibitive for all but the largest and most sophisticated market participants.

References

- Benos, Evangelos, et al. “The Cost of Clearing Fragmentation.” Bank of England Staff Working Paper, no. 800, 2019.

- Benos, Evangelos, et al. “The Cost of Clearing Fragmentation.” BIS Working Papers, no. 826, Bank for International Settlements, 2019.

- Duffie, Darrell, and Haoxiang Zhu. “Does a Central Clearing Counterparty Reduce Counterparty Risk?” The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2011, pp. 74-95.

- Duffie, Darrell, et al. “Policy Perspectives on OTC Derivatives Market Infrastructure.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 424, 2010.

- Garratt, Rod, and P. Zimmerman. “Centralized Netting and Systemic Risk.” Journal of Financial Intermediation, vol. 34, 2018, pp. 46-60.

- Menkveld, Albert J. “Crowding in Clearing.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 125, no. 3, 2017, pp. 433-454.

- Cont, Rama, and Amal Moussa. “The Structure of Systemic Risk in the European Financial Network.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2010.

- Huang, Wenqian. “The Cost of Clearing Fragmentation.” Nottingham Repository, 2022.

Reflection

The analysis of clearing fragmentation reveals a fundamental tension within modern market structure. The drive for competition and national regulatory oversight has produced a balkanized landscape that directly conflicts with the systemic goal of maximum capital efficiency. The data and operational mechanics show that the costs are real, quantifiable, and borne by all market participants through increased margins and distorted pricing. For any institution operating within this environment, the critical consideration becomes one of architectural resilience.

The knowledge of how fragmentation erodes netting benefits is the first layer of a necessary strategic response. The deeper question is how a firm’s internal operating system ▴ its combination of technology, quantitative models, and operational protocols ▴ is engineered to absorb these external frictions. Is your firm’s collateral management system merely a reactive utility for meeting margin calls, or is it a proactive, predictive engine for optimizing funding costs across a fragmented reality?

Is risk viewed as a monolithic portfolio, or does your architecture allow for a granular, venue-specific understanding of exposure and liquidity demands? The answers to these questions define the boundary between simply participating in the market and mastering its underlying structure for a durable competitive advantage.

Glossary

Central Counterparty

Multilateral Netting

Capital Efficiency

Initial Margin

Clearing Fragmentation

Interest Rate Swap

Fragmented Clearing

Ccp Basis

Liquidity Management

Treasury Management Systems

Margin Requirements

Collateral Optimization