Concept

The inquiry into the sizing of a Central Counterparty’s (CCP) default fund is an inquiry into the very architecture of market stability. From a systems perspective, the default fund is a load-bearing component within the financial market’s operating system. Its calibration determines the system’s resilience under acute stress.

It functions as a mutualized loss-absorbing mechanism, designed to ensure that the failure of one or more major participants does not cascade into a systemic collapse. The question of its size is a direct question about the level of systemic insurance the market is willing to provide for itself, and the price it is willing to pay for that security.

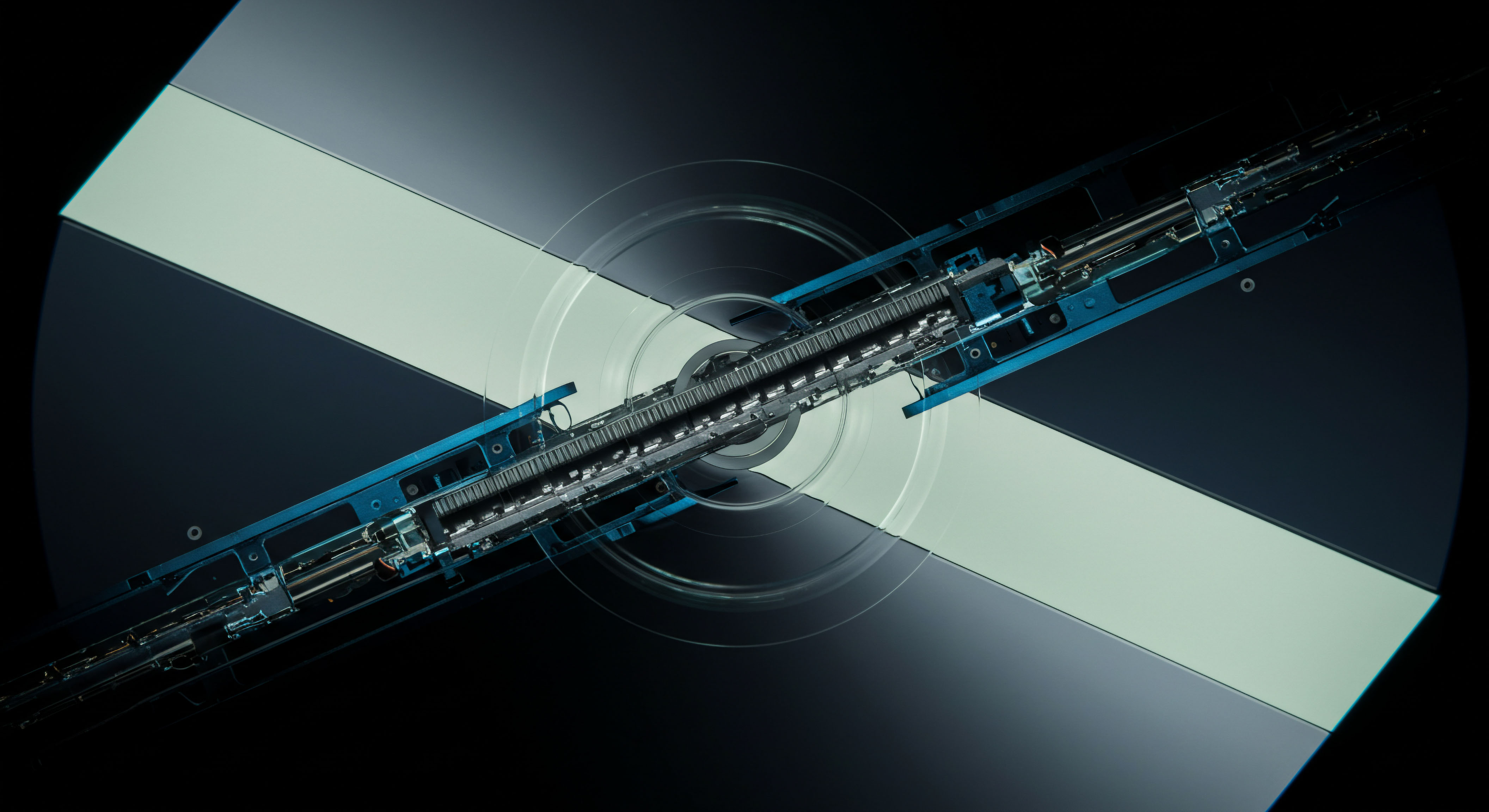

At its core, a CCP stands between buyers and sellers in derivatives markets, becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer through a process called novation. This elegant solution transforms bilateral counterparty credit risk into a more manageable, centralized risk concentrated at the CCP. To manage this concentrated risk, the CCP erects a multi-layered defense system known as the “default waterfall.” This is a predefined sequence for absorbing losses from a defaulting clearing member.

The member’s own initial margin is the first line of defense, followed by the defaulting member’s contribution to the default fund. Only then does the CCP commit its own capital, a layer often called “skin-in-the-game.” The final, and most critical, layer is the pooled, mutualized default fund contributions from all non-defaulting members.

A CCP’s default fund is the mutualized insurance pool designed to absorb the catastrophic losses from a member failure, thereby preventing a single default from causing a systemic market breakdown.

The sizing of this mutualized fund is where the central tension lies. A fund that is too small renders the entire structure fragile. If the losses from a major default exceed the fund’s capacity, the CCP itself could fail, triggering the very systemic crisis it was designed to prevent. This would shatter market confidence and lead to a catastrophic withdrawal of liquidity.

Conversely, a fund that is excessively large creates its own set of systemic problems. It acts as a constant drain on market liquidity, pulling capital from clearing members that could otherwise be used for investment and market-making activities. This can make clearing prohibitively expensive, potentially driving activity to less transparent, unregulated bilateral markets and paradoxically increasing systemic risk. An oversized fund can also create a dangerous sense of complacency, a form of moral hazard where members might engage in riskier behavior, assuming the massive fund will absorb any consequence. Therefore, the sizing of the default fund is a complex calibration exercise, balancing the need for robust protection against the risk of creating a liquidity-draining, incentive-distorting market structure.

The Default Waterfall Architecture

The default waterfall is the operational sequence for loss allocation. Understanding its structure is essential to grasping the role of the default fund. Each layer is designed to be exhausted before the next is tapped, creating a predictable and transparent process for managing a crisis. This predictability is, in itself, a tool for market stability.

- Defaulter’s Initial Margin This is the first resource to be used. It is capital posted by the defaulting member specifically to cover potential losses on their portfolio. It is a “defaulter pays” resource and is not mutualized.

- Defaulter’s Default Fund Contribution The next layer is the defaulting member’s own contribution to the mutualized default fund. This, too, is a “defaulter pays” resource.

- CCP’s Skin-in-the-Game (SITG) This is the CCP’s own capital, placed in the waterfall to demonstrate its commitment and align its incentives with those of the clearing members. It is a critical component for mitigating moral hazard.

- Non-Defaulting Members’ Default Fund Contributions This is the mutualized pool of capital. This is the layer where risk is shared among the surviving members. Its size and the rules governing its use are at the heart of the market stability debate.

- Recovery and Resolution Tools If the entire default fund is exhausted, the CCP moves to its recovery and resolution toolkit, which can include further cash assessments from surviving members or haircutting of variation margin gains. These are last-resort tools with significant potential to destabilize the market.

Why Is the Sizing a Foundational Concern?

The sizing of the default fund is a foundational concern because it directly influences the behavior of market participants and the flow of capital through the system. A well-sized fund, governed by transparent rules, fosters confidence. It allows participants to transact with the certainty that the system can withstand the failure of even a large peer. This confidence is the bedrock of market liquidity and efficient price discovery.

An improperly sized fund, whether too large or too small, distorts incentives and can introduce dangerous feedback loops into the market, transforming a localized default event into a system-wide crisis. The challenge is to find the optimal balance that provides security without crippling the market it is designed to protect.

Strategy

Strategically, the sizing of a CCP’s default fund is a complex optimization problem that balances three competing objectives ▴ systemic resilience, capital efficiency, and the mitigation of procyclical dynamics. The chosen strategy directly reflects a CCP’s risk appetite and its philosophical approach to its role as a Systemically Important Financial Market Utility (SIFMU). The prevailing international standard, known as “Cover 2,” dictates that a CCP’s default fund must be sufficient to withstand the simultaneous default of its two largest clearing members under extreme but plausible market conditions. This standard provides a clear, measurable benchmark for resilience.

The Cover 2 standard serves as the foundation of a CCP’s defensive strategy. Its purpose is to assure the market that the clearinghouse can absorb a catastrophic, multi-faceted failure without immediately needing to mutualize losses across the entire surviving membership in a disorderly fashion. The calculation is based on rigorous stress testing, where the CCP models the impact of severe market shocks ▴ such as extreme price moves, interest rate shifts, or volatility spikes ▴ on the portfolios of its largest members.

The resulting potential loss, after exhausting the defaulters’ initial margin, determines the required size of the default fund. This approach provides a tangible and defensible metric for resilience, which is critical for maintaining market confidence, especially during periods of stress.

The Procyclicality Dilemma

A significant strategic challenge in default fund sizing is managing procyclicality. Procyclicality refers to risk management practices that amplify market fluctuations. In the context of a CCP, this occurs when the need for default fund contributions increases during periods of market stress. As market volatility rises, the potential losses from a default also rise, prompting the CCP’s stress tests to demand a larger default fund.

The CCP must then issue cash calls to its members to top up the fund. These calls drain liquidity from the market at the precise moment it is most scarce. Clearing members, facing their own liquidity pressures, are forced to sell assets to meet these calls, which can further depress asset prices and exacerbate the initial stress event. This creates a dangerous feedback loop that can destabilize the market.

Calibrating a default fund requires a delicate balance; it must be large enough to absorb a catastrophic default but not so large that its funding mechanism drains critical liquidity during a crisis.

To counteract this, CCPs employ various anti-procyclicality (APC) tools. These can include using a floor for the fund size based on a longer look-back period for volatility, or using buffers and caps on how much contributions can increase over a short period. The strategic goal is to build a fund that is robust to stress without its own maintenance becoming a source of systemic risk.

Table Comparing Sizing Methodologies

| Sizing Methodology | Strategic Objective | Impact on Market Stability | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static “Cover 2” | Ensure resilience against the default of the two largest members based on periodic stress tests. | Provides a clear, high standard of resilience, fostering market confidence. | Can be highly procyclical if contribution requirements spike during market stress. |

| Dynamic with APC Buffers | Maintain “Cover 2” resilience while smoothing contribution requirements over time. | Reduces the risk of liquidity drains during stress, mitigating procyclical feedback loops. | May result in a fund that is temporarily underfunded relative to the most recent stress test results. |

| Economic Stress Testing | Size the fund based on forward-looking, hypothetical scenarios rather than purely historical data. | Can better prepare the CCP for unprecedented “black swan” events. | Scenarios are subjective and may be difficult to defend; can lead to excessively large fund requirements. |

Moral Hazard and the Role of Skin-In-The-Game

Another critical strategic consideration is the concept of moral hazard. A large, mutualized default fund can create a perception among clearing members that their individual risk-taking is subsidized by the collective. If a member believes that any catastrophic losses from their positions will be absorbed by the pooled fund, they may have less incentive to manage their risks prudently. This is a significant threat to long-term market stability.

The primary tool to combat this is the CCP’s own capital contribution to the default waterfall, its “skin-in-the-game” (SITG). By placing its own capital at risk before the non-defaulting members’ contributions are touched, the CCP demonstrates that it shares in the potential losses. This aligns the CCP’s incentives with those of its members. A larger SITG tranche gives the CCP a stronger incentive to rigorously monitor its members’ risk, enforce margin rules strictly, and develop a robust default management process.

The strategic debate centers on how large this SITG tranche should be. Members typically advocate for a larger SITG to ensure the CCP is sufficiently incentivized, while CCPs must balance this with the need to deploy their capital efficiently. The sizing of the SITG layer is a powerful signal to the market about the CCP’s commitment to prudent risk management.

Execution

The execution of a CCP’s default management process is a high-stakes, time-critical operation where the theoretical sizing of the default fund meets the practical realities of a market in crisis. The process is a predefined playbook designed to isolate a defaulting member, neutralize the risk of their portfolio, and restore the CCP to a matched book as quickly as possible, all while minimizing the impact on the broader market. The adequacy of the default fund is tested in real-time during this process. A shortfall at any stage can have cascading consequences, underscoring the importance of the preceding sizing and stress-testing exercises.

The Operational Playbook a Default Management Process

When a clearing member fails to meet its financial obligations, the CCP’s risk management and default management teams initiate a well-defined sequence of actions. This process is designed for speed and efficiency to prevent the defaulting member’s positions from deteriorating further in a volatile market.

- Declaration of Default The CCP’s risk committee, upon confirmation that a member has failed to meet a critical financial obligation (such as a margin call), formally declares the member in default. This triggers the legal and operational mechanisms outlined in the CCP’s rulebook.

- Information Gathering and Position Analysis The default management team immediately takes control of the defaulter’s entire portfolio. They conduct a rapid analysis to understand the size, complexity, and risk exposures of the positions. This includes identifying all associated assets, liabilities, and collateral.

- Risk Neutralization (Hedging) The immediate priority is to hedge the market risk of the defaulter’s portfolio. The team will execute trades in the open market to offset the directional exposure of the portfolio. This is a critical step to stop losses from accumulating while a more permanent solution is sought. The ability to execute these hedges effectively depends on market liquidity, which may be scarce during a crisis.

- Portfolio Auction The primary method for closing out the defaulter’s positions is to auction them off to other, non-defaulting clearing members. The CCP will typically break the portfolio into smaller, more manageable blocks to attract the widest possible range of bidders. The success of the auction is a critical determinant of the total loss. If the auction is successful and raises enough funds to cover the defaulter’s obligations, the crisis is contained. If the auction fails or the proceeds are insufficient, the CCP must move to the next stage.

- Application of the Default Waterfall This is the financial core of the default management process. The CCP applies the layers of the default waterfall in their prescribed order to cover any remaining losses:

- First The defaulter’s initial margin is seized and applied to the loss.

- Second The defaulter’s contribution to the default fund is used.

- Third The CCP’s own “skin-in-the-game” capital is applied.

- Fourth The CCP begins to draw upon the default fund contributions of the non-defaulting members, pro-rata to their contributions. This is the point of mutualization and a moment of significant market stress.

- Recovery and Replenishment If the default fund is depleted, the CCP must activate its recovery tools, which could involve cash calls for additional funds from surviving members. Following the event, the CCP must have a plan to replenish the default fund to its required level to ensure it is prepared for any future events.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

The sizing of the default fund is not a matter of guesswork. It is the output of sophisticated quantitative models and rigorous, data-driven stress testing. CCPs use these tools to estimate the potential losses they could face under extreme market conditions and ensure their financial resources are sufficient.

Table 1 Hypothetical Default Fund Contribution Calculation

This table illustrates how a CCP might calculate the required default fund contributions from its members based on their risk profiles. The contribution is often a function of the member’s average initial margin and their potential exposure under stress.

| Clearing Member | Average Initial Margin (IM) | Stress Test Exposure (STE) | Risk Weighting Factor | Calculated Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member A (Low Risk) | $50 million | $100 million | 10% | $10 million |

| Member B (Medium Risk) | $150 million | $400 million | 12% | $48 million |

| Member C (High Risk) | $300 million | $1.2 billion | 15% | $180 million |

| Member D (Low Risk) | $75 million | $150 million | 10% | $15 million |

Formula Note ▴ The “Calculated Contribution” is a simplified example, often derived from a more complex formula that might be Max(Base_Amount, Risk_Weight (STE – IM)). The goal is to ensure that members who contribute more to the CCP’s tail risk also contribute more to the default fund.

Predictive Scenario Analysis a Case Study

To understand the execution phase in practice, consider a hypothetical case study. A major geopolitical event unexpectedly disrupts global supply chains, causing unprecedented volatility in the commodity derivatives markets cleared by the “Global Commodities Clearing Corp” (GCCC). “Titan Trading,” a large clearing member with a highly concentrated and leveraged portfolio of oil futures, is caught on the wrong side of the market move.

Within hours, the value of Titan’s portfolio plummets. GCCC’s real-time risk systems flag Titan for an emergency intra-day margin call of $2 billion. Titan, facing its own liquidity crisis, fails to meet the call.

At 2:00 PM, GCCC’s Default Management Committee is convened, and by 2:30 PM, Titan Trading is formally declared in default. The playbook is now active.

GCCC’s first action is to attempt to hedge Titan’s massive short position in oil futures. But the market is now in a state of panic. Liquidity has evaporated, and bid-ask spreads have widened dramatically.

The hedging process is slow and costly, and the position continues to lose value. The total loss quickly surpasses Titan’s posted initial margin of $3 billion.

The next step is the portfolio auction. GCCC packages the remaining portfolio into five blocks and offers them to its 20 surviving clearing members. The market turmoil, however, makes members extremely risk-averse. They are unwilling to take on a large, volatile position, even at a discount.

Only two of the five blocks are sold, and at prices well below the current market mark. The auction is a partial failure, leaving GCCC with a massive, unhedged position and a realized loss of $7 billion.

Now, the default waterfall is applied in full force. The $3 billion in initial margin from Titan is gone. Titan’s own $500 million contribution to the default fund is consumed next. GCCC then applies its own $500 million “skin-in-the-game” contribution.

This leaves a remaining loss of $3 billion to be covered by the mutualized default fund. GCCC’s total default fund, sized according to the Cover 2 standard, is $10 billion. The CCP begins to draw on the contributions of its surviving members. This action sends a shockwave through the market.

The surviving members, now forced to recognize a loss on their default fund contributions, see their own capital positions weakened. They react by pulling back their trading activity and tightening lending standards to conserve liquidity, which further exacerbates the market crisis. While GCCC itself survives because the default fund was sufficient, the event demonstrates how the execution of the default process, even when successful, can have a significant chilling effect on market stability. The sizing of the fund was adequate to prevent the CCP’s failure, but its use created a significant procyclical shock to the financial system.

References

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures & International Organization of Securities Commissions. (2017). Framework for supervisory stress testing of central counterparties (CCPs). Bank for International Settlements.

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures & International Organization of Securities Commissions. (2022). Central Counterparty Financial Resources for Recovery and Resolution. Bank for International Settlements.

- Ghamami, S. (2022). Liquidity Management in Central Clearing ▴ How the Default Waterfall Can Be Improved. NYU Stern, Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions.

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association. (2015). CCP Default Management, Recovery and Continuity ▴ A Proposed Recovery Framework. ISDA.

- Norman, P. (2021). What kind of thing is a Central Counterparty? The Role of Clearing Houses as a Source of Policy Controversy. LSE Research Online.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. (2017). Central Counterparty Margin Frameworks. RBA Bulletin.

- Bank of England. (2023). 2023 CCP Supervisory Stress Test ▴ results report.

- Gere-Gubistyi, R. & Vargiolu, T. (2018). What do central counterparty default funds really cover? A network-based stress test answer. Journal of Network Theory in Finance.

- CCP Global. (2020). CCP12 PRIMER ON CREDIT STRESS TESTING.

Reflection

Calibrating the System’s Core

The analysis of a CCP’s default fund architecture moves us beyond a simple discussion of risk buffers. It compels us to view the clearing system as a dynamic, interconnected machine. The sizing of the fund is a primary calibration knob for this entire system. Adjusting it changes the machine’s performance characteristics, its resilience, and the behavior of the operators who rely on it.

The knowledge gained here is a component in a larger system of institutional intelligence. How does this specific component ▴ the default fund ▴ interact with your own firm’s risk management framework? Does your operational model treat the CCP as a simple utility, or as a dynamic system with its own feedback loops and potential instabilities? The ultimate strategic edge is found in understanding not just the individual components of the market, but the systemic connections between them. A superior operational framework is built upon this deeper, architectural understanding.

Glossary

Central Counterparty

Market Stability

Default Waterfall

Clearing Member

Default Fund Contributions

Skin-In-The-Game

Clearing Members

Systemic Risk

Default Fund

Initial Margin

Mutualized Default Fund

Moral Hazard

Surviving Members

Recovery and Resolution

Cover 2 Standard

Stress Testing

Risk Management

Procyclicality

Default Management Process