Concept

The question of validator centralization and its impact on network censorship resistance is often approached as a pathology to be cured. This perspective, while common, misses the systemic reality. Centralization is an emergent property, a gravitational force born from economies of scale, user convenience, and the relentless pursuit of optimized returns. It is a fundamental condition of the network’s economic physics, not an anomaly.

Understanding its relationship with censorship resistance, therefore, requires a shift in perspective from merely identifying a problem to architecting a system that accounts for these inherent centralizing pressures as a baseline state. The core of the issue resides in how a network’s consensus mechanism translates economic power into political power ▴ the power to determine which transactions are included in the immutable public ledger.

At its heart, censorship resistance is the guarantee that any valid transaction, provided it meets the network’s protocol requirements such as a fee, will eventually be included in a block. This property is the bedrock of a permissionless system. Without it, a blockchain becomes a distributed database administered by a privileged set of actors, its neutrality compromised. The impact of validator centralization is the systematic erosion of this guarantee.

When a small number of entities control a significant portion of the validation rights, whether through staked assets in a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) system or hashrate in a Proof-of-Work (PoW) system, they create a small, concentrated surface for external pressure. State-level actors, regulators, or any entity with sufficient leverage can coerce these few key validators to exclude specific types of transactions, effectively censoring participants at the protocol level.

The concentration of validation power creates an attack vector where a few entities can be compelled to enforce jurisdictional rules, undermining the network’s core value proposition of permissionless access.

Defining the Axis of Censorship

The threat of censorship materializes along a spectrum, which can be understood through two distinct modalities ▴ weak censorship and strong censorship. This distinction is critical for a precise diagnosis of the system’s vulnerabilities. Each type represents a different level of threat to the network’s operational integrity and the user’s ability to transact freely.

Weak censorship describes a scenario where certain validators or miners refuse to include specific transactions in the blocks they produce. This results in a degradation of user experience, as the censored transaction must wait for a non-censoring validator to be selected to propose the next block. While the transaction is not permanently barred from the network, its inclusion is delayed.

The quantitative impact of this delay is significant; on the Ethereum network following the OFAC sanctions on Tornado Cash, the average inclusion delay for targeted transactions increased by 85%. This latency can have severe financial consequences in time-sensitive applications like decentralized finance (DeFi), where it can exacerbate the risk of sandwich attacks or cause trades to fail due to price slippage.

Strong censorship represents a far more severe threat. This occurs when an economic majority of the network, typically more than 51% of the staking power or hashrate, actively colludes to perpetually exclude certain transactions. In such a scenario, the targeted transaction would never be included on the canonical chain, effectively resulting in a permanent loss of the user’s ability to transact with their assets.

This form of censorship directly attacks the liveness of the blockchain, as a supermajority of validators could, in theory, refuse to build upon any chain history that includes transactions they wish to censor. A formal proof demonstrates that no PoS protocol can achieve censorship resilience if more than 50% of the validator committee engages in censorship, establishing a hard security boundary for these systems.

The Inevitable Pull toward Consolidation

To architect a resilient system, one must first understand the forces driving the consolidation of validator power. These forces are not malicious in their intent; they are rational economic responses to the protocol’s incentive structure. In PoS systems like Ethereum, the primary drivers are the complexities of validator operations and the economics of staking.

Running a validator node effectively requires technical sophistication, constant uptime, and vigilance against security threats. For the average token holder, this operational burden is a significant barrier. Furthermore, the potential for financial loss through “slashing” ▴ a penalty for validator misbehavior or downtime ▴ creates a substantial risk. These factors create a powerful incentive for individual stakers to delegate their assets to large, professional staking pools.

Services like Lido and centralized exchanges such as Coinbase offer a convenient solution, abstracting away the technical complexity and socializing the risk of slashing in exchange for a fee. The result is a natural aggregation of stake into a few dominant pools. Following Ethereum’s transition to PoS, the top three validator entities controlled over 51% of the staked ETH, crossing the critical threshold for a potential strong censorship attack.

A secondary, yet equally potent, centralizing force is the pursuit of Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). MEV refers to the profit a validator can make by strategically ordering, including, or excluding transactions within the blocks they produce. Extracting MEV efficiently requires sophisticated algorithms and infrastructure, creating a competitive environment where specialized, well-capitalized entities outperform smaller operators.

This dynamic further encourages smaller validators to join larger pools to gain access to a share of these outsized MEV rewards, reinforcing the cycle of centralization. The architecture of the system itself, through its incentive mechanisms, channels power toward a consolidated core.

Strategy

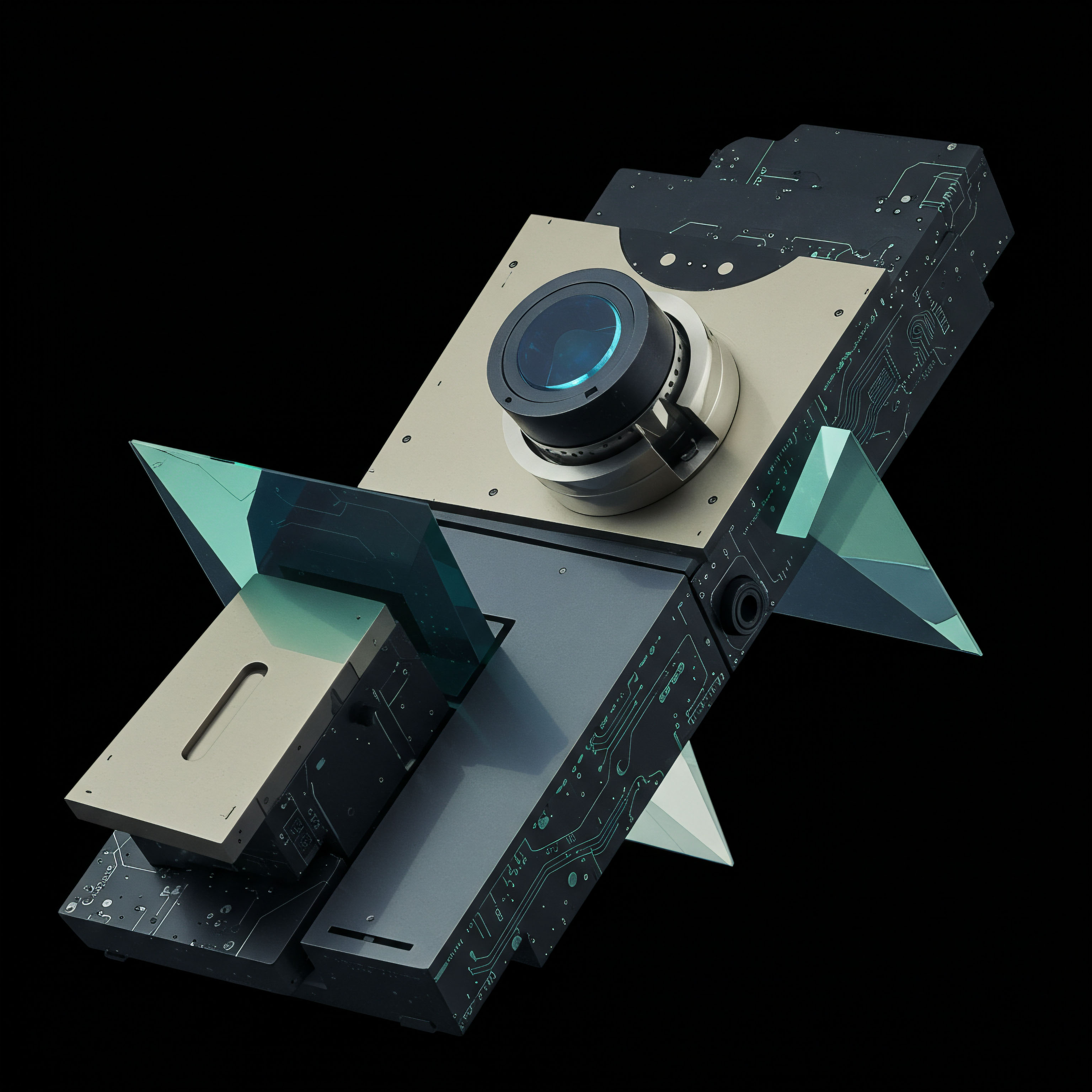

Addressing the systemic risk posed by validator centralization requires strategic interventions at the protocol level. The objective is to disrupt the direct line between economic power and the ability to censor transactions. The most prominent strategic framework developed to counteract this vulnerability is Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS).

This approach redesigns the block production process, creating a system of checks and balances intended to insulate the network from the censorship decisions of a few powerful actors. PBS deconstructs the monolithic role of the validator into two distinct functions ▴ the block builder and the block proposer.

In the PBS model, builders are specialized, sophisticated entities that compete to construct the most profitable block possible. They do this by aggregating transactions from the public mempool and private order flows, optimizing their ordering to maximize MEV and transaction fees. They then submit their constructed blocks, along with a bid representing the payment to the proposer, to a marketplace. The proposer, who is the validator chosen by the consensus protocol for a given slot, simply selects the block with the highest bid from this marketplace without needing to see its contents.

This separation is a critical strategic maneuver. It allows the validator (proposer) to earn MEV rewards without needing the complex infrastructure to extract it, thus reducing the economic pressure that drives stake centralization. More importantly, it creates an opportunity to introduce mechanisms that enforce censorship resistance.

Proposer-Builder Separation functions as a strategic decoupling, inserting a specialized marketplace between transaction ordering and block validation to mitigate direct censorship control.

A Multi-Layered Defense System

The PBS framework is not a single solution but a foundation upon which multiple layers of defense can be built. Its effectiveness hinges on creating a competitive and transparent market for blockspace that makes censorship economically and reputationally costly. This involves several interconnected components designed to work in concert.

- Block Relays ▴ These act as trusted intermediaries between builders and proposers. Builders submit their blocks to a relay, which verifies the block’s validity and the bid’s value. The relay then forwards only the block header and the bid to the proposer. The proposer selects the most profitable header, and only after committing to it does the relay reveal the full block contents. This blind commitment prevents the proposer from stealing the builder’s profitable transaction ordering (MEV). However, relays themselves introduce a new point of centralization and potential censorship. Following the OFAC sanctions, the dominant relay, Flashbots, began censoring transactions related to Tornado Cash, immediately extending its censorship policy to the significant portion of the network that utilized its service.

- Censorship Resistance Lists (crLists) ▴ To counter the censorship power of builders and relays, the concept of a crList was introduced. A crList is a set of transactions that a proposer can force a builder to include in their block. If a builder submits a block that does not include the transactions from the proposer’s crList, the proposer can reject the block. This mechanism re-empowers the proposer to enforce network neutrality, providing a direct tool to override a censoring builder’s decisions. It creates an economic trade-off for the builder ▴ comply with the censorship resistance demand or risk having your profitable block rejected entirely.

- Encrypted Mempools ▴ A more advanced strategic defense involves encrypting transactions in the mempool. In this model, builders cannot see the contents of transactions when they are constructing blocks; they can only see the fees offered. The transactions are only decrypted after they have been finalized on-chain. This approach effectively blinds any potential censor, as they cannot identify which transactions to exclude. It strikes at the root of the problem by removing the information necessary to perform targeted censorship. This strategy also has the secondary benefit of neutralizing toxic forms of MEV, such as front-running, further leveling the playing field for all users.

The Market Dynamics of Censorship

The strategic interplay between these components creates a complex market for block production. The decision to censor is not merely a technical or ethical choice; it is an economic and strategic one, shaped by the incentives and competitive pressures within this market. The table below illustrates the distribution of block production among different actors in the post-merge Ethereum ecosystem and their stance on censorship, providing a clear picture of the centralization landscape.

| Entity Type | Entity Name | Market Share of Blocks | Censorship Stance (Post-OFAC Sanctions) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block Builder | Flashbots Builders | ~22.2% | Censoring | |

| Block Builder | Builder0x69 | ~11.4% | Censoring | |

| Block Builder | BloXroute (Regulated) | ~10.7% (Combined) | Censoring | |

| Block Builder | Beaverbuild | ~3.5% | Non-Censoring | |

| Block Relay | Flashbots Relay | ~46.0% | Censoring | |

| Block Relay | BloXroute (Max Profit) | ~5.2% | Non-Censoring | |

| Block Relay | Eden | ~1.9% | Non-Censoring |

The data reveals a significant concentration of power among a few actors who chose to implement censorship. At the time of the study, actors responsible for building or relaying at least 46% of all Ethereum blocks were actively censoring. This demonstrates how quickly external regulatory pressure can be translated into on-chain censorship when the block production pipeline is centralized. However, the analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York adds a crucial layer of nuance.

It found that the largest block proposers, who collectively validate about 40% of blocks, consistently chose to accept blocks from non-censoring builders, even when those blocks offered lower fees than their censoring counterparts. This suggests that for some of the most significant players in the ecosystem, the principle of censorship resistance is valued as a core feature of the network, outweighing short-term profit maximization. Their strategic stance acts as a powerful countervailing force, ensuring a market for non-censoring builders and maintaining a pathway for all valid transactions to reach the chain.

Execution

The execution of censorship within a centralized validator set is a function of control over the block production lifecycle. From the moment a transaction is broadcast to the network to its final inclusion in a block, there are specific chokepoints where a censoring entity can intervene. The primary mechanism is exclusion from the block template.

A censoring validator, or a builder serving a validator pool, will operate with a blacklist of addresses or smart contract interactions. When constructing a block, their software will simply ignore any transactions in the mempool that match this blacklist, effectively leaving them stranded.

This process has a direct and measurable impact on the network’s performance and security, quantified by transaction confirmation latency. A transaction’s “time in mempool” is a critical metric; the longer it waits for inclusion, the more vulnerable it becomes to various risks. For the censored transaction, the delay is obvious ▴ it must wait for a non-censoring block producer. What is less obvious is the cascading effect this has on the entire network.

The study of Ethereum’s mempool following the OFAC sanctions provides a granular view of this impact. The operational decision by major builders and relays to censor transactions created a bifurcated mempool, where certain transactions were systematically delayed, waiting for the subset of non-censoring validators to win a proposal slot.

Censorship is executed through deliberate transaction exclusion, creating measurable inclusion delays that degrade network security and compromise user experience.

Quantitative Analysis of Inclusion Latency

The operational impact of validator centralization on censorship resistance can be precisely quantified by analyzing the change in transaction inclusion times. The period surrounding the OFAC sanctions on Tornado Cash serves as a natural experiment, revealing the direct consequences of censorship policies implemented by dominant market actors. The data demonstrates a statistically significant increase in the time it took for targeted transactions to be included on-chain, and also highlights a general increase in latency for all transactions after the network’s transition to PoS and the adoption of the PBS architecture.

The following table provides a quantitative breakdown of these execution delays, comparing the average time a transaction spent in the mempool before and after the sanctions, and distinguishing between censored and non-censored transactions. The data illustrates the concrete cost of censorship, measured in seconds of additional risk and uncertainty imposed on users.

| Time Period | Transaction Type | Average Inclusion Delay (Seconds) | Standard Deviation | Primary Network State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 2022 (Pre-Merge) | Censored (Tornado Cash) | 15.8 | 22.8 | Proof-of-Work / OFAC Sanctions Active |

| November 2022 (Post-Merge) | Censored (Tornado Cash) | 29.3 | 23.9 | Proof-of-Stake / PBS Adopted |

| November 2022 (Post-Merge) | Non-Censored | 8.7 | 8.3 | Proof-of-Stake / PBS Adopted |

Data derived from the analysis in “Blockchain Censorship” (arXiv:2305.18545v2).

The results are stark. The average inclusion delay for Tornado Cash transactions nearly doubled, jumping from 15.8 seconds to 29.3 seconds after the Merge and the widespread adoption of PBS, which was dominated by censoring relays. This 85% increase represents a tangible degradation of service for users interacting with the sanctioned application. It also reveals a broader trend ▴ even non-censored transactions saw a baseline latency of 8.7 seconds in the PBS environment.

The increased complexity of the multi-party block production pipeline ▴ involving builders, relays, and proposers ▴ introduces inherent delays compared to the previous model where a single miner controlled the entire process. This operational overhead is a direct trade-off made to enable the strategic benefits of PBS.

The Finality Threshold and Systemic Risk

The most severe execution risk of validator centralization is the threat to network liveness, which is formalized by an impossibility result ▴ a PoS blockchain cannot guarantee censorship resilience if more than 50% of its validators are censoring. This is not a probabilistic risk; it is a deterministic failure threshold. If this line is crossed, the censoring majority can simply refuse to attest to or build upon any block proposed by the non-censoring minority. Their collective inaction would prevent the chain from finalizing, effectively halting the network for any transaction they wish to exclude.

This creates a critical security parameter for any PoS network. The defense against such an attack is no longer purely technical but relies on the social layer. In the event of a strong censorship attack by a majority coalition, the only recourse for the non-censoring minority is to coordinate off-chain to execute a User-Activated Soft Fork (UASF). This would involve the community agreeing to adopt a new version of the protocol that punishes the censoring validators, likely by slashing their stake and ejecting them from the validator set.

This is a drastic, last-resort measure. It is a contentious and complex process that requires robust social consensus, highlighting that the ultimate backstop for protocol-level censorship is the coherence and commitment of the network’s community. The execution of such a defense is fraught with challenges, including achieving consensus on the forking point and ensuring the new chain retains its economic value, but it remains the fundamental failsafe against a captured validator set.

References

- Wahrstätter, Anton, et al. “Blockchain Censorship.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.18545, 2023.

- Ang, Henry, et al. “Censorship Resistance in Bitcoin & Ethereum.” Bixin Ventures, Medium, 25 Oct. 2022.

- Durfee, Jon, and Michael Lee. “How Censorship Resistant Are Decentralized Systems?” Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 14 Feb. 2025.

- Karakostas, Dimitris, Aggelos Kiayias, and Christina Ovezik. “SoK ▴ A Stratified Approach to Blockchain Decentralization.” Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2022.

- Buterin, Vitalik. “State of research ▴ Increasing censorship resistance of transactions under proposer/builder separation (PBS).” Ethereum Research, 2021.

- Seira, Rodrigo, Amy Aixi Zhang, and Dan Robinson. “Base Layer Neutrality.” Paradigm, 2022.

- Tas, Ertem Nusret, et al. “Bitcoin-enhanced proof-of-stake security ▴ Possibilities and impossibilities.” Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2022.

Reflection

The data and mechanics of validator centralization lead to an unavoidable conclusion. Censorship resistance is not a static property achieved at a protocol’s genesis. It is a dynamic equilibrium, continuously negotiated between the economic forces of centralization and the strategic commitment of the network’s participants.

The evidence that major proposers would forgo higher fees to uphold network neutrality suggests that the system’s resilience is underwritten by more than just code and economic incentives. It is also a product of conviction.

A System of Active Defense

This reality reframes the challenge from one of designing a perfectly decentralized system ▴ a likely impossibility given the laws of economic gravity ▴ to one of architecting a system for perpetual defense. The framework of Proposer-Builder Separation, crLists, and the ultimate recourse of a social fork are the tools of this defense. They acknowledge the existence of centralizing pressures and create mechanisms to hold them in check.

The future integrity of permissionless networks will depend on the vigilance of their communities and the willingness of their most powerful actors to prioritize the long-term value of neutrality over the short-term gains of optimization. The system is designed to be tested, and its strength is revealed not in the absence of pressure, but in its response to it.

Glossary

Censorship Resistance

Proof-Of-Stake

Average Inclusion Delay

Tornado Cash

Staking Pools

Maximal Extractable Value

Proposer-Builder Separation

Block Production

Block Builder