Concept

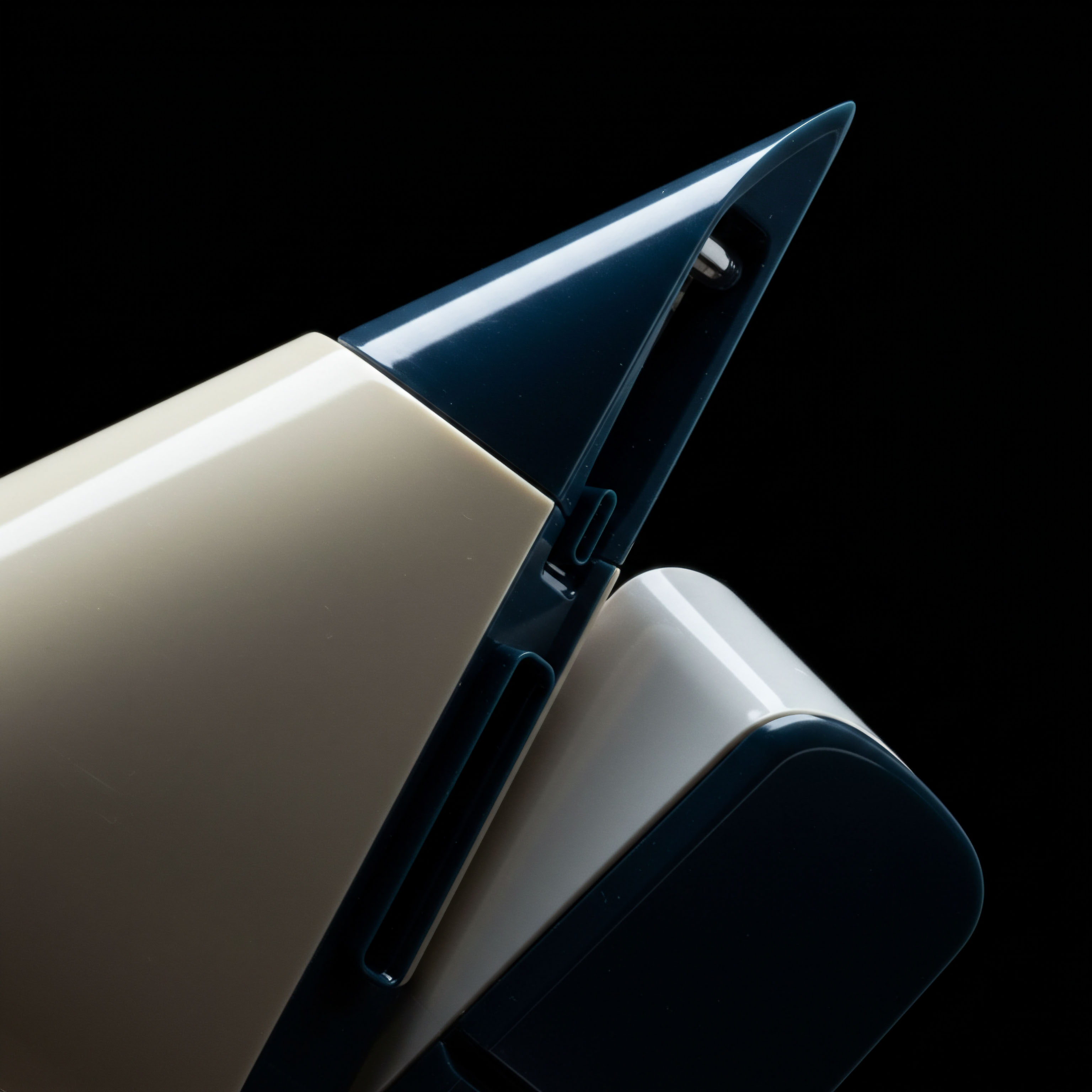

An institutional trader operating within the market’s intricate architecture confronts the winner’s curse not as a singular phenomenon, but as a multifaceted risk vector whose expression is fundamentally dictated by the trading protocol itself. The curse’s manifestation within a Request for Quote (RFQ) system possesses a distinct character when compared to its effects in a public, multilateral auction like an Initial Public Offering (IPO). The core distinction resides in the structure of information asymmetry. An IPO auction is a common value problem played out on a public stage.

A multitude of participants, each with their own private estimate, bid for an asset that will ultimately have a single, unified market price post-auction. The winner is the participant whose private estimate was most optimistic, often leading to an overpayment relative to the consensus value that emerges once trading begins.

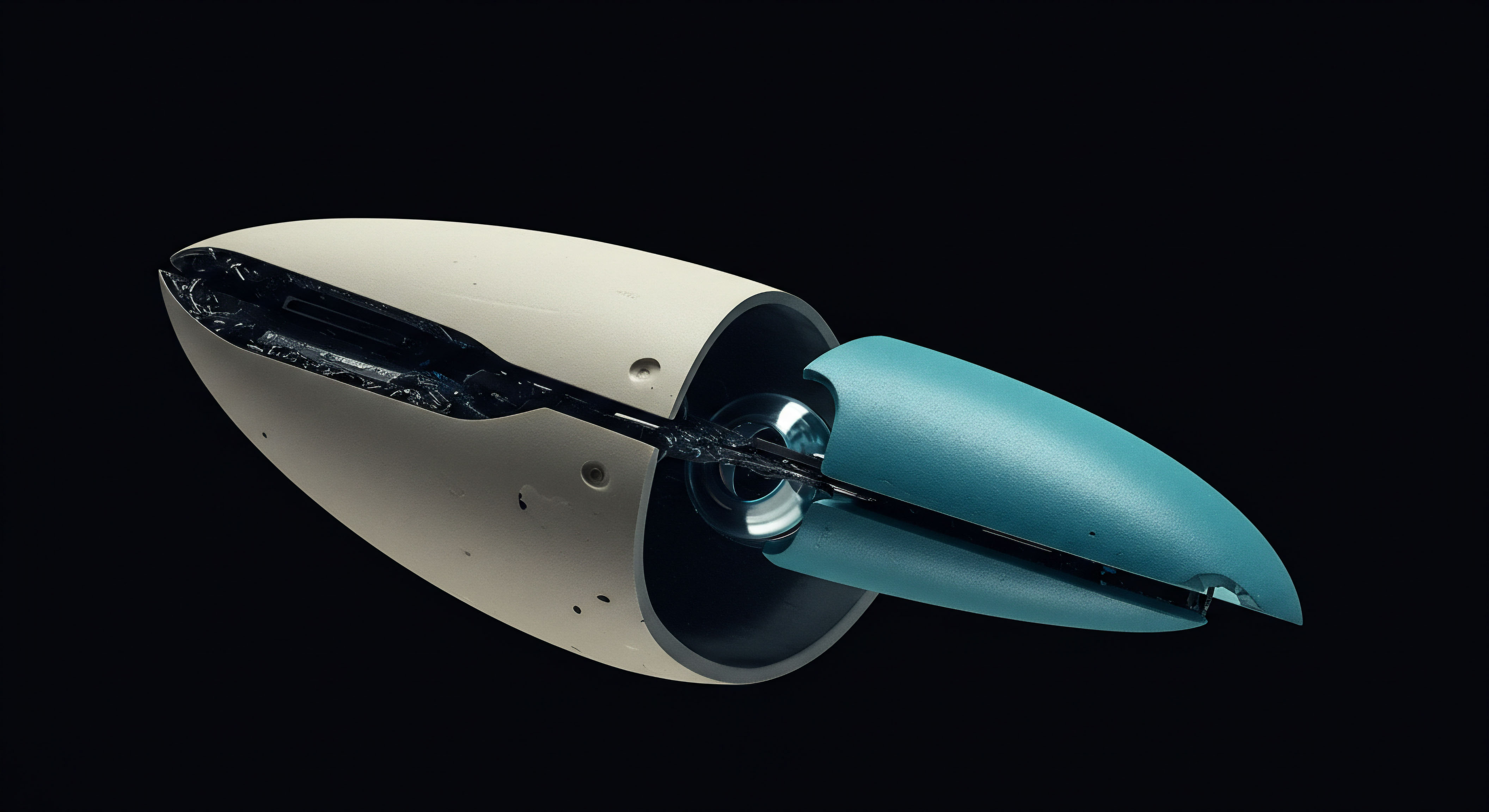

The RFQ protocol operates within a different informational paradigm. It is a bilateral, discreet negotiation. The entity requesting the quote initiates a private query to a select group of liquidity providers. Here, the winner’s curse is experienced primarily by the price-maker (the dealer), and it is a direct function of adverse selection.

The dealer who “wins” the trade by providing the most competitive quote does so with the implicit risk that the requester possesses superior, short-term information about the asset’s future price movement. The curse is realized when the dealer buys an asset just before its value drops or sells an asset just before its value rises, with the client’s acceptance of the quote acting as the confirmation of the dealer’s informational disadvantage.

The winner’s curse in an IPO stems from overestimating a common value, while in an RFQ, it arises from being adversely selected by a better-informed counterparty.

Information Structure in IPOs

In an IPO auction, all bidders are attempting to value the same asset, the “common value.” The information asymmetry is diffuse and horizontal. Each bidder conducts their own due diligence, creating a private signal or estimate of the company’s worth. The auction mechanism aggregates these disparate signals into a single clearing price. The participant who most overestimates the value places the highest bid and “wins” the allocation.

The curse is the subsequent discovery that their valuation was an outlier compared to the collective wisdom of the market, which becomes apparent when the stock begins trading and a consensus price is established. The risk is a function of the number of bidders; a larger pool of participants increases the probability that at least one will have a significant overestimation.

Information Structure in RFQs

The RFQ mechanism presents a vertical and concentrated information asymmetry. The requester, often a large institutional client, may have a sophisticated analytical basis for the trade, such as a large fundamental portfolio rebalance or knowledge of an impending market-moving event. The dealer, in contrast, must price the asset based on public market data and their own models, while attempting to infer the requester’s informational advantage. The “win” for the dealer is executing the trade.

The “curse” is the immediate financial loss if the trade was prompted by the client’s superior information. This transforms the problem from one of valuing a common good to one of pricing the risk of being the uninformed party in a transaction.

Strategy

Strategic responses to the winner’s curse are contingent on the specific market structure in which a participant operates. The countermeasures employed in a public IPO auction are structurally different from the risk management frameworks used by dealers in a bilateral RFQ system. The former involves adjusting one’s own valuation to account for statistical bias, while the latter requires a sophisticated system for pricing counterparty risk.

Strategic Mitigation in IPO Auctions

An informed participant in an IPO auction must approach the bidding process with the understanding that winning implies their valuation is likely the most optimistic. The primary strategy to counteract the winner’s curse is to bid below one’s own private valuation. This downward adjustment should, in theory, account for the “bad news” inherent in winning the auction. The size of this adjustment is a function of several factors:

- Number of Bidders ▴ As the number of competing bidders increases, the likelihood that the winner has significantly overestimated the asset’s value also rises. A rational bidder should become more conservative, lowering their bid as the field of competitors grows.

- Uncertainty of Value ▴ For assets with high intrinsic value uncertainty (e.g. a biotech firm with a single drug in trials), the range of private valuations will be wide. This variance increases the potential magnitude of the winner’s curse, necessitating a more substantial downward bid adjustment.

- The Free-Rider Problem ▴ A significant complication in IPO auctions is the presence of uninformed “free-rider” investors. These participants rely on the research of others and may bid aggressively, assuming the clearing price will be set by more informed players. This behavior can inflate the final price and exacerbates the winner’s curse for all participants, as it forces even informed bidders to pay more than they otherwise would.

How Do Dealers Strategically Price RFQs?

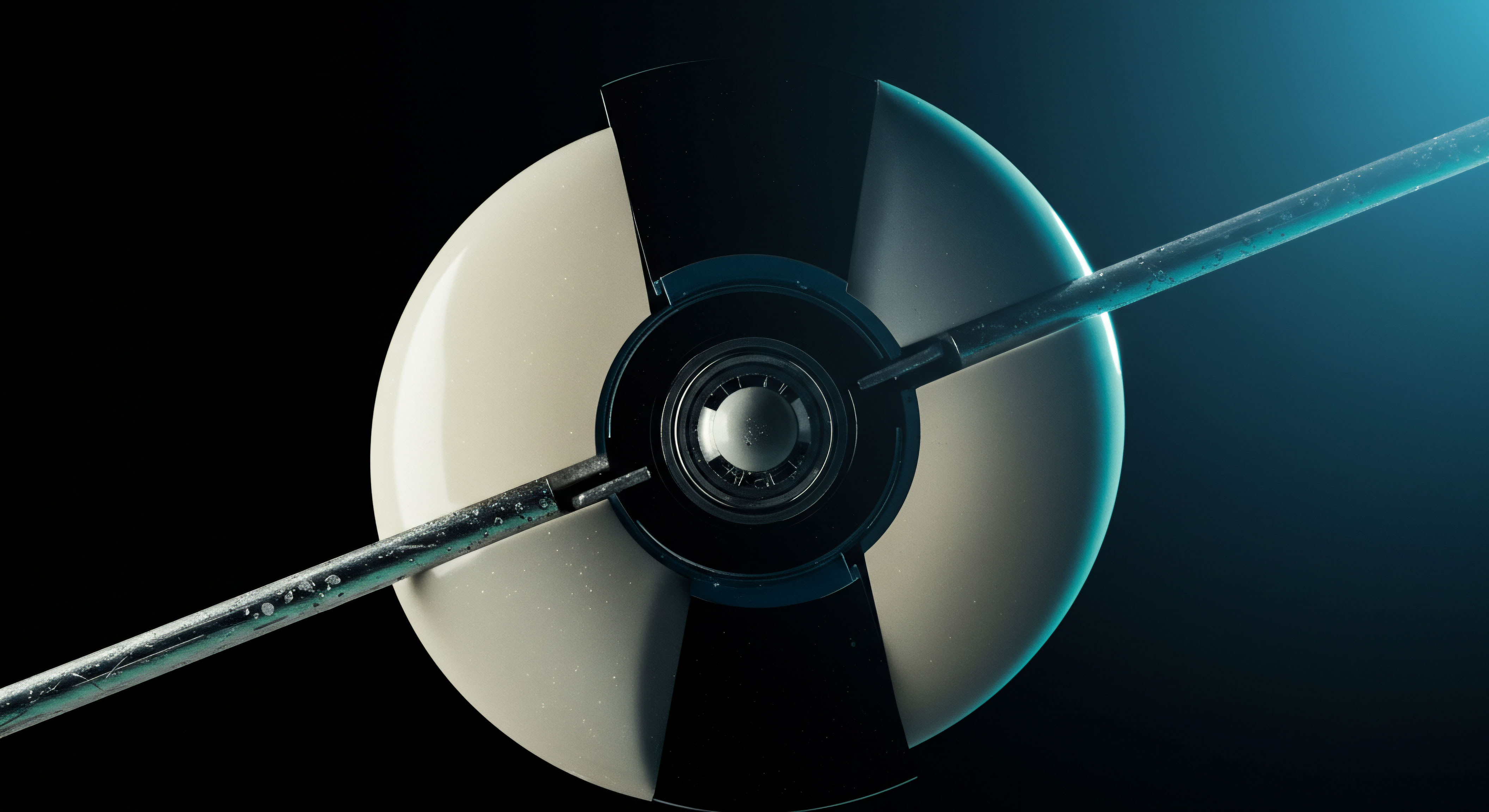

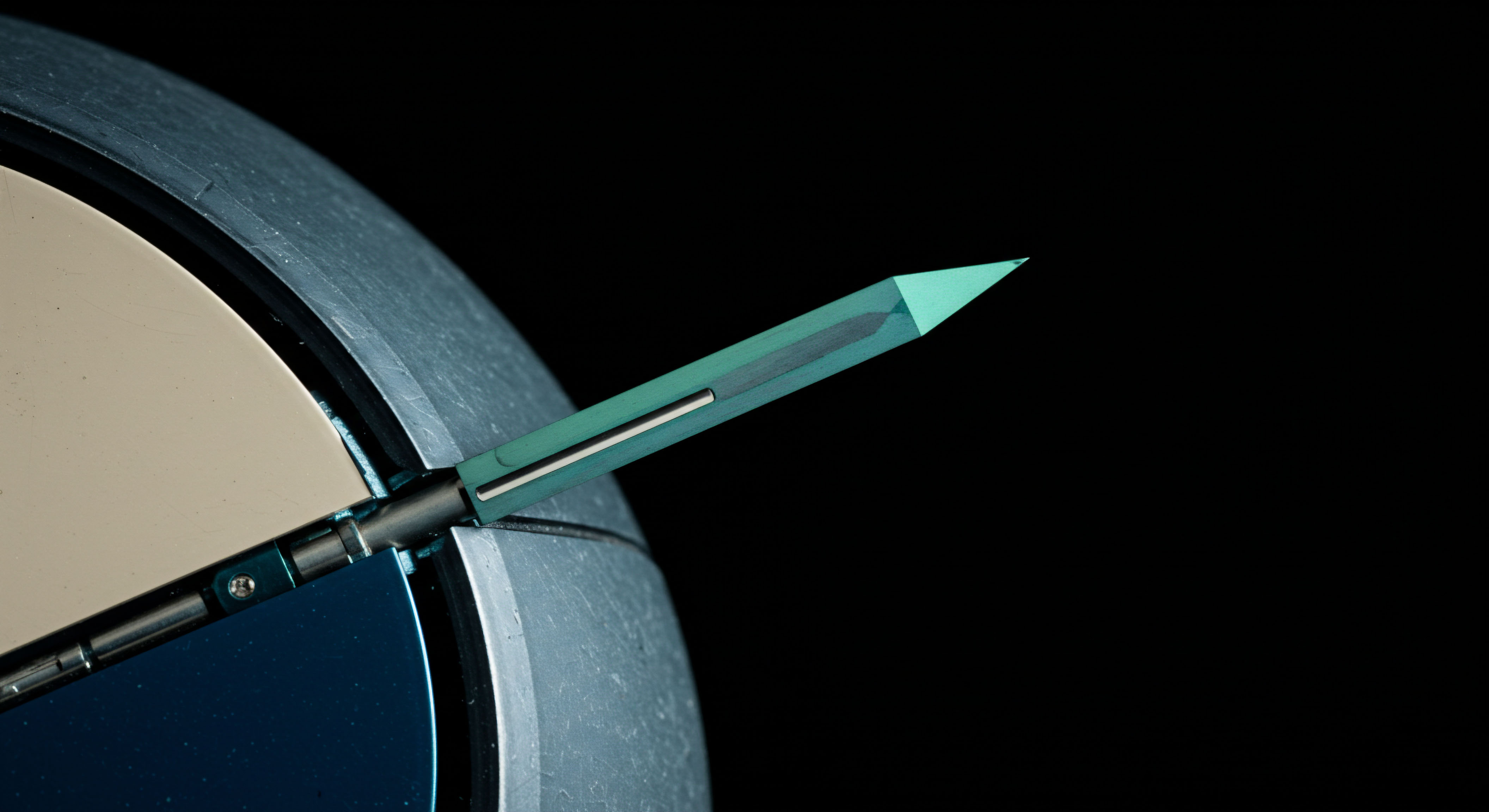

For a liquidity provider in an RFQ system, the strategy centers on managing adverse selection. The dealer’s profit is derived from the bid-ask spread, and this spread must be wide enough to compensate for the occasions they trade with a counterparty who has a significant informational edge. The pricing strategy is dynamic and systematic.

Dealers build sophisticated models to calculate the appropriate spread for each quote. This involves quantifying the potential for adverse selection. The core idea is to “price in” the risk. Key inputs into this pricing engine include:

- Client Tiering ▴ Dealers classify clients based on their historical trading behavior. Clients whose past trades have consistently preceded adverse market movements for the dealer are deemed “high risk” or “informed.” These clients will receive wider spreads on their quotes compared to clients whose trading flow is considered less directional or “uninformed.”

- Trade Size and Asset Volatility ▴ Larger trades and more volatile assets carry greater risk. A large request in a volatile stock is a strong signal of a potentially significant, undisclosed piece of information. The dealer’s spread will widen accordingly to compensate for the increased potential loss.

- Market Conditions ▴ During periods of low liquidity or high uncertainty, the risk of adverse selection increases. Dealers will systematically widen all quotes to protect themselves from trading on stale prices or against clients with better access to real-time information.

A rational IPO bidder shades their bid downwards to correct for optimism, whereas a rational RFQ dealer widens their spread outwards to price in counterparty information risk.

The following table provides a comparative analysis of the strategic frameworks for managing the winner’s curse in these two distinct environments.

| Strategic Dimension | IPO Public Auction | RFQ Bilateral Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Risk | Common Value Overestimation | Adverse Selection |

| Source of Curse | Winning against a large field of bidders, indicating an outlier valuation. | Winning a quote from a better-informed counterparty. |

| Core Strategy | Downward adjustment of one’s private valuation (Bid Shading). | Dynamic widening of the bid-ask spread to price the risk of information asymmetry. |

| Key Inputs | Estimated number of bidders, asset value uncertainty, presence of uninformed bidders. | Counterparty trading history, trade size, asset volatility, prevailing market liquidity. |

| Successful Outcome | Acquiring the asset at a price that does not exceed its post-auction market consensus value. | Maintaining a profitable trading book over time by ensuring spreads earned from uninformed flow cover losses from informed flow. |

Execution

The execution mechanics of an IPO auction and an RFQ protocol are the operational bedrock upon which their respective versions of the winner’s curse are built. Analyzing these procedural flows reveals precisely how and when the curse is realized, moving from theoretical risk to tangible financial outcome. For the institutional operator, understanding this level of granularity is paramount for designing robust risk management systems.

Execution Mechanics of a Uniform-Price IPO Auction

A uniform-price auction, often called a Dutch auction, aims to allocate shares at a single price to all successful bidders. The process unfolds in a series of discrete, highly structured steps. Consider a hypothetical IPO for a technology company, “Innovate Corp.”

- Bidding Phase ▴ Investors submit sealed bids specifying the number of shares they are willing to buy and the maximum price they are willing to pay. There is no visibility into competing bids.

- Clearing Price Determination ▴ After the bidding period closes, the bids are ranked from highest price to lowest. The underwriter moves down the list, aggregating the number of shares requested at each price level, until the total number of shares offered in the IPO is accounted for. The price of the lowest successful bid becomes the “clearing price” for the entire offering. All bidders who bid at or above this clearing price are awarded shares at this single price.

- The Curse in Action ▴ The winner’s curse materializes for those who bid significantly higher than the clearing price. Their high bid secured their allocation, but it also signals a substantial overestimation of the collective market valuation.

The table below models the clearing price determination for Innovate Corp’s 10 million share IPO and illustrates the impact of the winner’s curse.

| Bidder | Bid Price ($) | Shares Requested | Cumulative Shares | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investor A | 35.00 | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | Wins allocation at $30.00; High overestimation |

| Investor B | 34.00 | 2,000,000 | 3,000,000 | Wins allocation at $30.00; Significant overestimation |

| Investor C | 32.00 | 3,000,000 | 6,000,000 | Wins allocation at $30.00; Moderate overestimation |

| Investor D | 30.00 | 4,000,000 | 10,000,000 | Sets Clearing Price; Wins allocation at $30.00 |

| Investor E | 29.00 | 5,000,000 | 15,000,000 | Loses allocation; Bid below clearing price |

In this scenario, the clearing price is $30.00. Investor A, who was willing to pay up to $35.00, experiences the winner’s curse most acutely. Their valuation was an extreme outlier. If Innovate Corp. begins trading on the secondary market at $28.00, the curse is fully realized as an immediate capital loss for all winning bidders.

Execution Mechanics of an RFQ and the Dealer’s Curse

The RFQ execution protocol is a discreet, sequential process. The winner’s curse for the dealer is the financial loss resulting from being “picked off” by an informed client. This is a game of speed, information, and precise risk pricing.

How Is Adverse Selection Priced in RFQs?

A dealer’s quoting engine is an automated system designed to provide two-sided markets while protecting the firm from adverse selection. The process for a single RFQ is as follows:

- Inbound RFQ ▴ A client requests a quote to sell 100,000 shares of a specific stock.

- Risk Parameter Calculation ▴ The dealer’s system instantly pulls data:

- The current National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO).

- The historical trading behavior of the specific client (their “toxicity” score).

- The real-time volatility of the stock.

- The dealer’s current inventory in that stock.

- Spread Determination ▴ The system calculates a unique bid price for this specific request. The base is the current market bid, but it is adjusted downwards based on the risk parameters. A highly “toxic” client requesting a large trade in a volatile stock will receive a significantly lower bid price than an uninformed client.

- Quote Dissemination and Acceptance ▴ The dealer sends the quote. The client has a short window (often seconds or milliseconds) to accept. If the client accepts the dealer’s bid, the dealer is now long 100,000 shares.

- The Curse Realized ▴ The winner’s curse for the dealer occurs if, moments after the trade, negative news about the stock becomes public and the market price drops sharply. The dealer “won” the trade but was adversely selected, resulting in a loss on their new position. The client’s decision to sell was based on information the dealer did not have.

In an IPO, the curse is a post-auction reckoning with the market’s consensus value; in an RFQ, the curse is the dealer’s immediate, post-trade loss to a better-informed counterparty.

The management of this risk is the central operational challenge for any market-making firm that utilizes RFQ protocols. It requires a significant investment in technology, data analysis, and quantitative modeling to ensure that the firm can systematically price the risk of adverse selection across thousands of daily trades.

References

- Thaler, Richard H. “The Winner’s Curse.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 2, no. 1, 1988, pp. 191-202.

- Kagel, John H. and Dan Levin. “The Winner’s Curse and Public Information in Common Value Auctions.” The American Economic Review, vol. 76, no. 5, 1986, pp. 894-920.

- Rock, Kevin. “Why New Issues Are Underpriced.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 15, no. 2, 1986, pp. 187-212.

- Akerlof, George A. “The Market for ‘Lemons’ ▴ Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 84, no. 3, 1970, pp. 488-500.

- Grossman, Sanford J. and Joseph E. Stiglitz. “On the Impossibility of Informationally Efficient Markets.” The American Economic Review, vol. 70, no. 3, 1980, pp. 393-408.

- Jagannathan, Ravi, and Ann E. Sherman. “Why Do IPO Auctions Fail?” Kellogg Insight, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, 1 May 2007.

- Harris, Larry. Trading and Exchanges ▴ Market Microstructure for Practitioners. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Madhavan, Ananth. “Market Microstructure ▴ A Survey.” Journal of Financial Markets, vol. 3, no. 3, 2000, pp. 205-258.

Reflection

The architectural differences between public auctions and bilateral quote systems reveal a deeper truth about market risk. The nature of the information flow dictates the expression of that risk. An operational framework built solely to mitigate the statistical bias of over-optimism in an auction setting would be wholly inadequate for managing the predatory information risk inherent in a dealer-client relationship. This prompts a critical examination of an institution’s own trading protocols.

Does your risk management system adapt its logic to the specific structure of the liquidity venue? Is the risk of adverse selection quantified and priced with the same rigor as market risk or credit risk? The ultimate strategic advantage lies in designing an operational system that recognizes and prices these distinct informational structures with precision.

Glossary

Information Asymmetry

Request for Quote

Adverse Selection

Rfq

Clearing Price

Common Value

Risk Management

Ipo Auction

Liquidity Provider

Bid-Ask Spread

Execution Protocol