Concept

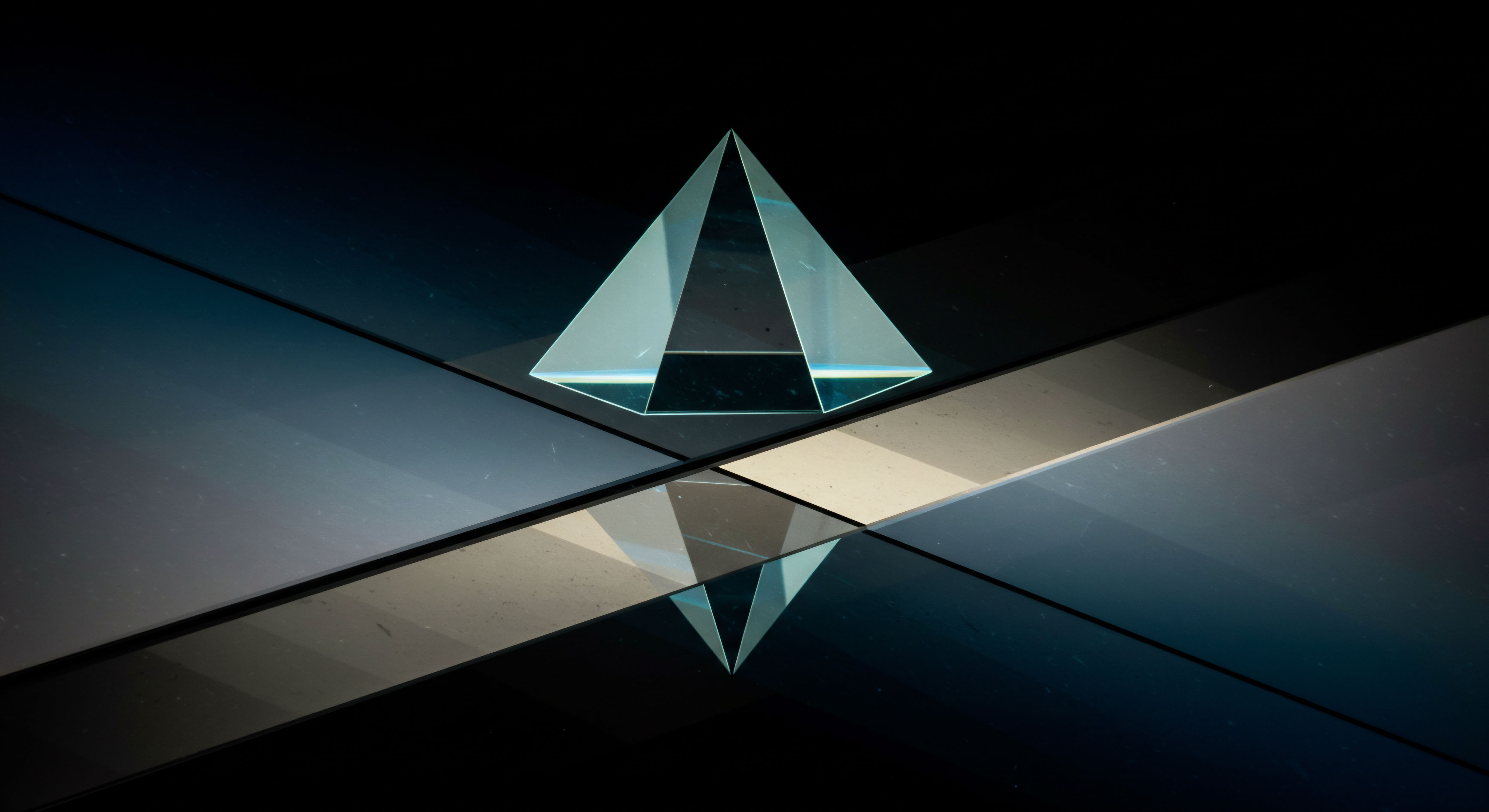

The phenomenon known as the winner’s curse is a structural feature of any market where assets with common value are exchanged under conditions of incomplete information. It describes the predicament where the winning participant in a competitive bidding process has likely overpaid relative to the asset’s intrinsic worth. This occurs because the winner is, by definition, the participant with the most optimistic, and therefore often most inaccurate, assessment of value. Understanding this curse is fundamental to navigating institutional trading, as its manifestation and the strategies to mitigate it differ profoundly between distinct market structures like a Request for Quote (RFQ) system and a traditional, open-cry or electronic auction.

A traditional auction, whether for a physical commodity like an oil tract or a financial instrument, operates on a principle of centralized, competitive price discovery. All participants compete simultaneously, their bids influencing one another in a dynamic, often public, forum. In this environment, the winning bid is the one that triumphs over all others, creating a direct feedback loop.

The very act of winning provides new, and often sobering, information ▴ every other participant valued the asset less. This immediate, post-win realization that one’s valuation was an outlier is the classic presentation of the winner’s curse, a direct consequence of the auction’s open and competitive architecture.

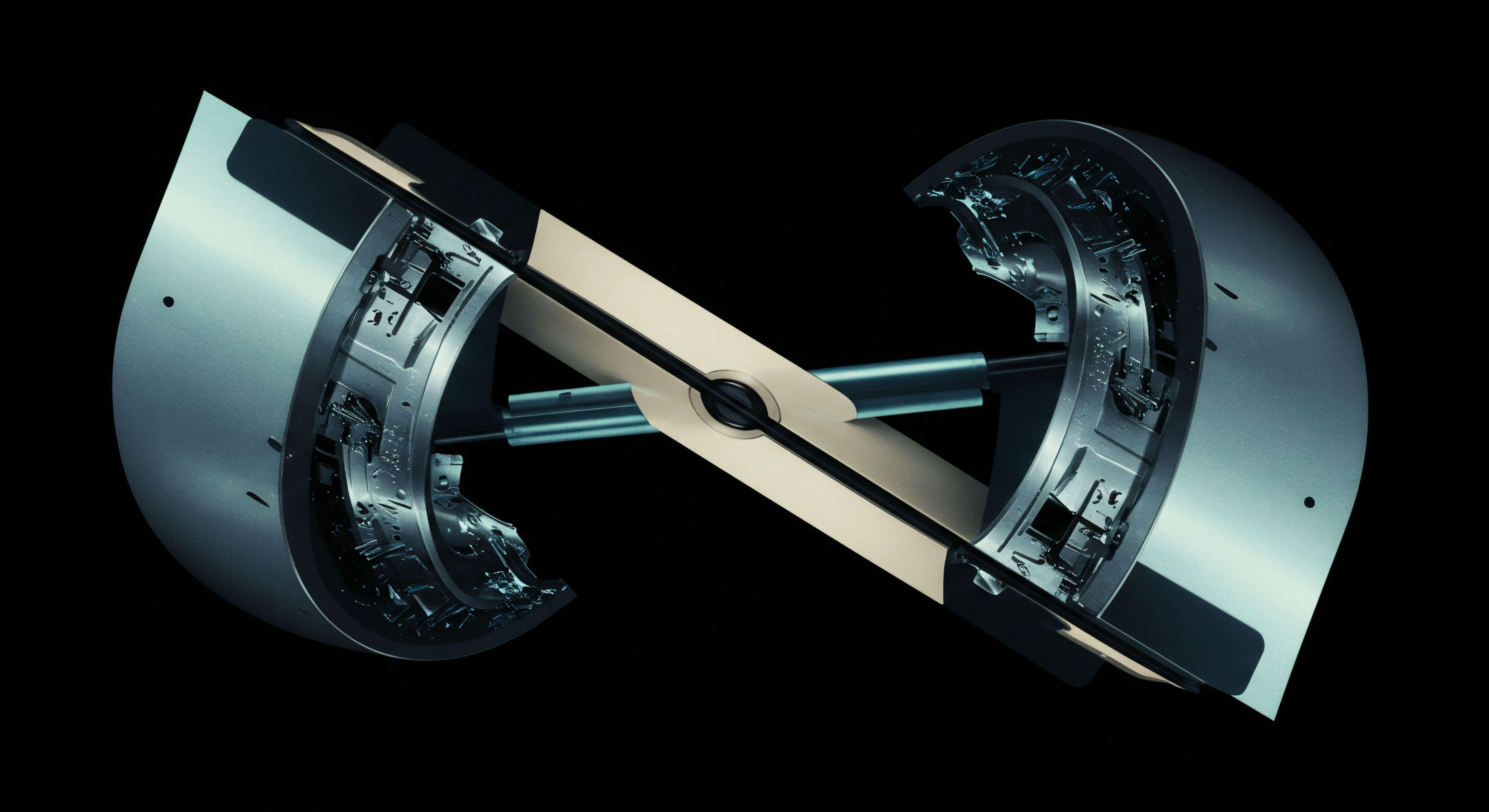

The RFQ protocol functions through a fundamentally different architecture of information and risk. Instead of an open, all-to-all competition, an RFQ is a decentralized, bilateral, or p-to-p (peer-to-peer) price discovery mechanism. A liquidity seeker confidentially solicits quotes from a select group of liquidity providers (dealers). This structure compartmentalizes information.

The dealers do not see each other’s quotes, and the seeker is the sole nexus of information. The competition is indirect and mediated. This design alters the nature of the winner’s curse, shifting it from a public spectacle of overvaluation to a more subtle, private risk of mispricing based on limited counterparty signals.

The core distinction lies in the flow of information; traditional auctions centralize competitive data, while RFQs decentralize and compartmentalize it, fundamentally altering how the winner’s curse is experienced.

In essence, the two systems represent different philosophies of market interaction. The traditional auction is a system designed for maximum price discovery through open competition. The RFQ protocol is a system designed for controlled, discreet execution, prioritizing minimal information leakage over broad price discovery. Consequently, the winner’s curse in an auction is a curse of public victory, while in an RFQ, it becomes a curse of private, bilateral negotiation, where the “winner” (the selected dealer) may have mispriced their quote based on an incomplete understanding of the seeker’s full intentions or the broader market’s immediate state.

Strategy

Strategic approaches to mitigating the winner’s curse are contingent upon the specific market structure in which a participant operates. The divergent architectures of traditional auctions and RFQ systems demand distinct strategic frameworks for both liquidity seekers and providers. The primary differentiating factor is the management of information asymmetry and the nature of the competitive landscape.

Information Leakage and Strategic Bid Shading

In a traditional auction, all bids contribute to a collective, real-time pool of information. A participant’s strategy must account for the fact that their actions are visible and that the final winning price will reflect the aggregated sentiment of the entire market. The primary tool to combat the winner’s curse here is “bid shading.” A rational bidder must bid below their true estimated value of the asset. The degree of this shading is a function of the number of competitors and the perceived distribution of their valuations.

The more bidders there are, the more likely it is that someone holds an overly optimistic estimate, and thus, the more aggressively one must shade their own bid to avoid overpaying. The strategy is defensive, predicated on anticipating the collective behavior of a crowd.

Conversely, the RFQ protocol creates a system of information silos. A dealer providing a quote does not know how many other dealers are competing, nor do they know the prices being offered by their unseen rivals. This opacity changes the strategic calculus. The risk is not of being the most optimistic in a crowd, but of misjudging the seeker’s reservation price or the current market state known to the seeker.

A dealer’s strategy revolves around accurately modeling the seeker’s intent and the likely competitiveness of the request. A quote that is too aggressive (a high bid or low offer) may win the trade but result in a loss if the dealer misjudged the true market. A quote that is too conservative will never win. The “shading” in an RFQ is therefore based on a model of a single counterparty’s behavior, not the wisdom of a crowd.

Comparative Strategic Frameworks

The table below outlines the key strategic differences demanded by each protocol.

| Strategic Element | Traditional Auction | Request for Quote (RFQ) Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Risk Focus | Public overpayment due to being the most optimistic bidder in an open field. | Private mispricing due to incomplete information about the seeker’s full context and competitive landscape. |

| Information Structure | Centralized and often transparent. Bids are aggregated, revealing market-wide sentiment. | Decentralized and opaque. Dealers operate in information silos, blind to competing quotes. |

| Competitive Dynamic | Direct, all-to-all competition. Each participant bids against every other participant. | Indirect, hub-and-spoke competition. Dealers compete against each other only through the seeker. |

| Core Mitigation Tactic | Bid shading based on the number of bidders and estimated market-wide valuations. | Quote precision based on modeling the seeker’s behavior, urgency, and likely market information. |

| Post-Trade Information | Winning reveals you had the highest valuation among all participants. | Winning reveals your quote was the most favorable among a select, unknown group of dealers. |

The Seeker’s Advantage and the Dealer’s Dilemma

In an RFQ, the liquidity seeker holds a significant informational advantage. They are the only participant with a complete view of all submitted quotes. This allows the seeker to identify the best price with precision.

For the dealers, this creates a “winner’s curse” scenario where the winning dealer is the one who has offered the most aggressive price, potentially underestimating the risk or overestimating their ability to hedge. A sophisticated dealer’s strategy must therefore incorporate a dynamic pricing model that adjusts for this inherent structural disadvantage.

The RFQ system transforms the winner’s curse from a problem of market psychology into a game-theoretic challenge of modeling a single, better-informed counterparty.

Factors a dealer might consider include:

- Past behavior ▴ The seeker’s history of accepting or rejecting quotes.

- Market conditions ▴ The volatility and liquidity of the instrument at the time of the request.

- Inferred urgency ▴ The size and timing of the request may signal the seeker’s need for immediate execution.

A traditional auction, by contrast, levels the informational playing field to a greater degree. While some participants may have superior private information, the bidding process itself generates public signals that all can interpret. The strategic challenge is less about modeling a single adversary and more about correctly interpreting the public signals generated by the auction mechanism itself.

Execution

The execution mechanics of traditional auctions and RFQ protocols are where the theoretical differences in structure and strategy manifest as tangible operational realities. For institutional traders, portfolio managers, and principals, understanding these execution differences is paramount to achieving capital efficiency and mitigating the adverse effects of the winner’s curse.

Protocol Mechanics and Risk Management

The execution of a trade in a traditional auction, such as on a central limit order book (CLOB), is governed by a clear set of rules applied uniformly to all participants. Priority is typically determined by price and then time. The winner’s curse arises from the very process of “lifting” an offer or “hitting” a bid.

To execute a large order, a trader must consume liquidity from the book, and the final price paid is the volume-weighted average price (VWAP) of the executed fills. The fact that you were able to secure a large fill means you were willing to pay more than all other resting orders, confirming you are the market’s most aggressive participant at that moment.

RFQ execution is a bilateral, off-book process. The steps are distinct:

- Initiation ▴ A seeker sends a request for a specific instrument and size to a curated list of dealers.

- Quotation ▴ Each dealer responds with a firm, executable quote within a specified time frame. This quote is private between the dealer and the seeker.

- Execution ▴ The seeker reviews the quotes and can choose to execute with the dealer offering the best price. The trade is then reported, but the competing quotes remain confidential.

The winner’s curse for the winning dealer is the realization that their internal pricing model produced the most aggressive quote of the group. This could be due to a superior model, but it could also signal that their model failed to account for a market factor that other dealers correctly identified, leading to a “toxic” flow. The execution risk for the dealer is immediate; they are now holding a position acquired at a price that no other competitor was willing to offer.

Quantitative Impact on Execution Price

The impact of the winner’s curse can be modeled to understand the potential costs. Consider a scenario where a seeker wants to buy a block of an asset with a true market value (which is unknown to the bidders) of $100.00.

| Participant / System | Estimated Value / Quote | Outcome | Winner’s Curse Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auction Bidder A | $101.50 | Loses Auction | N/A |

| Auction Bidder B | $102.10 | Loses Auction | N/A |

| Auction Bidder C (Winner) | $102.75 | Wins at ~$102.11 (2nd price) | Pays $2.11 above true value. |

| RFQ Dealer 1 | $100.50 | Quote not selected | N/A |

| RFQ Dealer 2 (Winner) | $100.25 | Wins the trade | Pays $0.25 above true value. |

| RFQ Dealer 3 | $100.40 | Quote not selected | N/A |

In this simplified model, the auction’s public competition drives the price higher, and the winner (Bidder C) explicitly overpays, realizing they were the most optimistic. In the RFQ, the competition is for the tightest spread. The winning dealer (Dealer 2) still “overpays” relative to the true value, but the mechanism of private, competitive quoting contains the extent of the overpayment.

The curse manifests as the dealer winning the trade at a price that was more aggressive than their peers, forcing them to immediately manage a potentially unprofitable position. The seeker, in this case, benefits from the dealers’ fear of missing the trade, securing a price closer to the true market value.

Execution protocols are the final arbiter of strategy; the RFQ’s discreet nature contains the winner’s curse’s financial impact, while the auction’s transparency amplifies it.

Ultimately, the choice between these protocols depends on the seeker’s objectives. An auction provides transparent, albeit potentially costly, price discovery. An RFQ provides discreet, controlled execution that can mitigate the winner’s curse for the seeker by transferring the risk to the winning dealer. For the dealer, participation in an RFQ system requires sophisticated pricing models and a deep understanding of counterparty behavior to avoid consistently being the “winner” in a cursed trade.

References

- Bergemann, Dirk, Benjamin Brooks, and Stephen Morris. “Countering the winner’s curse ▴ Optimal auction design in a common value model.” American Economic Journal ▴ Microeconomics 9.3 (2017) ▴ 30-72.

- Thaler, Richard H. “The winner’s curse.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2.1 (1988) ▴ 191-202.

- Capen, E. C. R. V. Clapp, and W. M. Campbell. “Competitive bidding in high-risk situations.” Journal of Petroleum Technology 23.6 (1971) ▴ 641-653.

- Kagel, John H. and Dan Levin. “The winner’s curse and public information in common value auctions.” The American Economic Review 76.5 (1986) ▴ 894-920.

- Milgrom, Paul R. and Robert J. Weber. “A theory of auctions and competitive bidding.” Econometrica ▴ Journal of the Econometric Society (1982) ▴ 1089-1122.

- O’Hara, Maureen. Market Microstructure Theory. Blackwell Publishers, 1995.

- Harris, Larry. Trading and Exchanges ▴ Market Microstructure for Practitioners. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Reflection

Systemic Information Integrity

The choice between an auction and an RFQ protocol is a decision about the architecture of information flow. Viewing these mechanisms as distinct systems for managing risk and discovering price provides a more powerful analytical lens than simply labeling them as ways to buy and sell. A traditional auction is a system of public aggregation, designed to produce a single, consensus price from a multitude of competing signals.

An RFQ is a system of private interrogation, designed to extract a specific price from a select group under conditions of controlled information release. The winner’s curse is not a flaw in these systems, but an inherent, emergent property of their design.

Considering this, an institution’s operational framework should be evaluated on its ability to select the appropriate information architecture for a given trade. The critical question becomes ▴ for this specific asset, at this particular moment, does our strategic objective benefit from public price discovery or from private, discreet negotiation? Understanding the fundamental differences in how the winner’s curse manifests in each system allows a principal to move beyond simply executing trades and toward designing an execution policy that structurally manages information risk, thereby creating a durable competitive advantage.

Glossary

Request for Quote

Rfq

Traditional Auction

Price Discovery

Rfq Protocol

Information Asymmetry

Bid Shading

Execution Risk