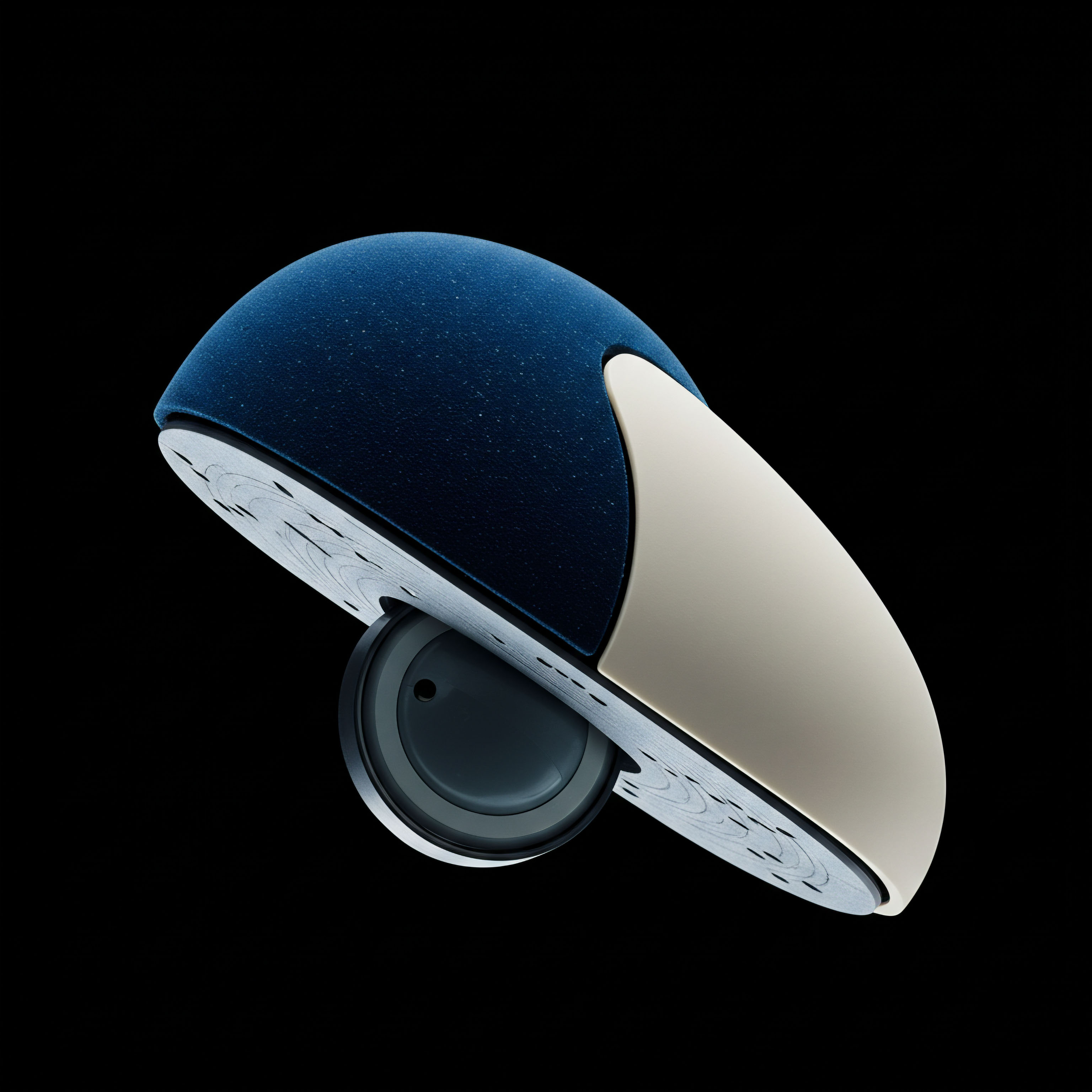

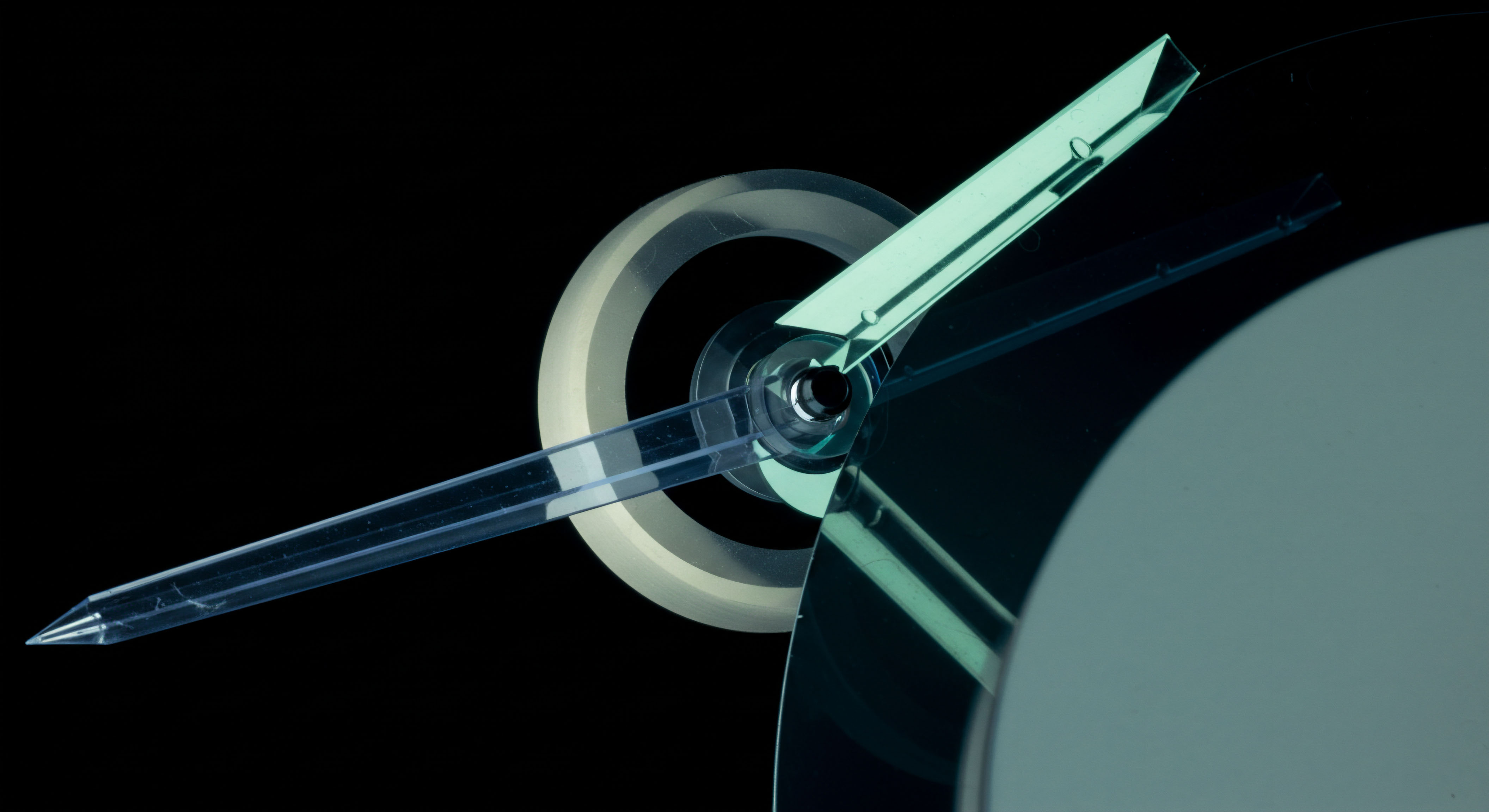

Concept

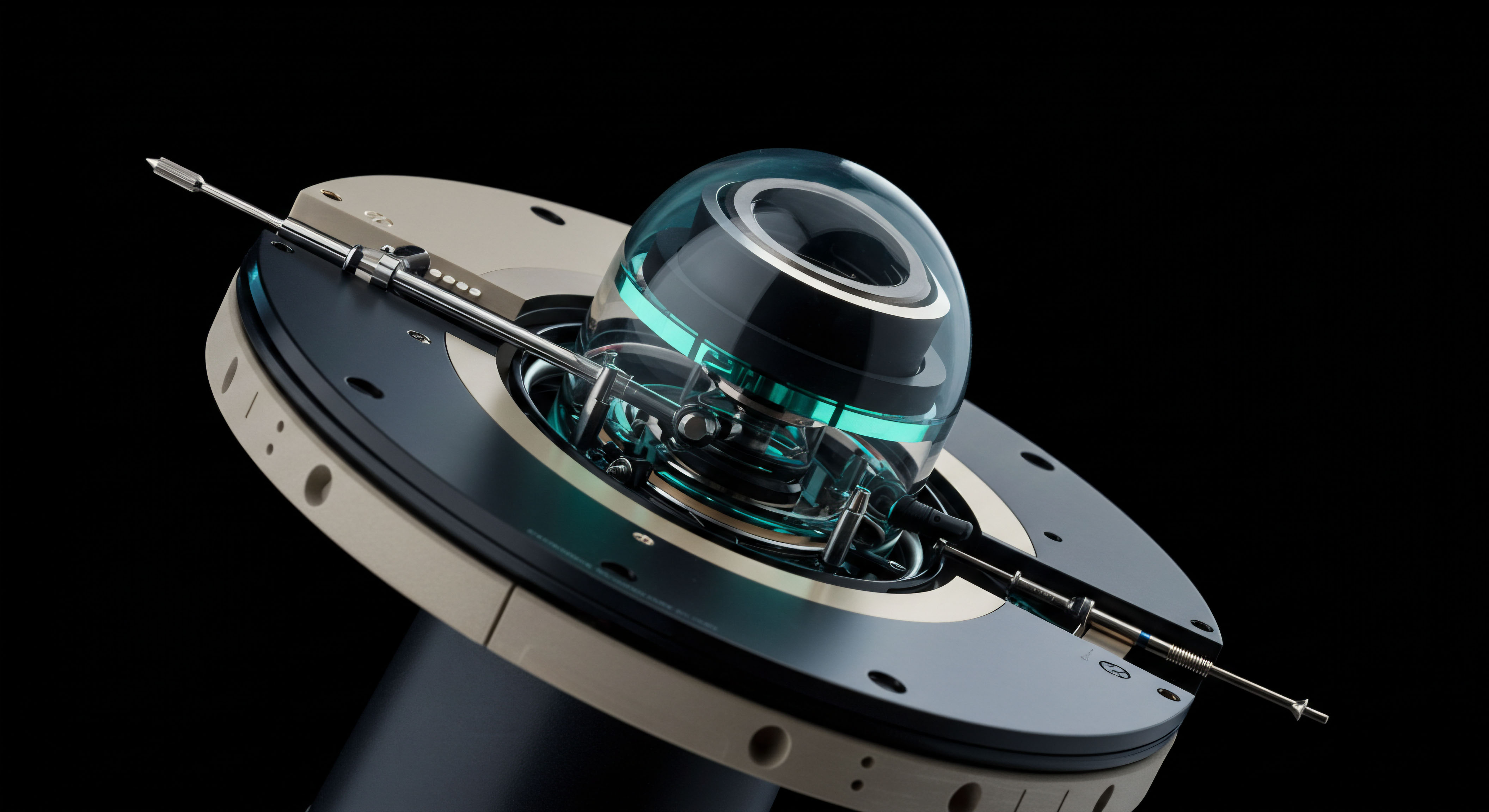

An evaluation of counterparty risk within institutional trading systems moves beyond a simple tally of potential defaults. It represents a fundamental analysis of the structural integrity of a transaction’s lifecycle. The distinction between a Request for Quote (RFQ) protocol and a Central Counterparty Clearing (CCP) model is an examination of two separate philosophies for managing the risk of non-performance. One system isolates risk bilaterally, treating each transaction as a discrete, private contract.

The other mutualizes risk, absorbing it into a collective, system-wide buffer. Understanding the key differences is an exercise in appreciating how market architecture directly shapes risk topology.

In a bilateral execution model, such as the RFQ, counterparty risk is a direct and specific liability between two parties. When an institution solicits and accepts a quote, it enters into a binding agreement with a single dealer. The resulting exposure is entirely concentrated on that dealer’s ability to perform. This creates a web of distinct, point-to-point risk vectors across the market.

Each institution is responsible for its own due diligence, establishing credit lines, and negotiating legal frameworks like the ISDA Master Agreement for each relationship. The risk is granular, manageable on an individual basis, and transparent to the two entities involved. The integrity of the system relies on the creditworthiness of each individual node in the network.

Counterparty risk management evolves from a series of bilateral negotiations in RFQ systems to a standardized, system-wide insurance mechanism under central clearing.

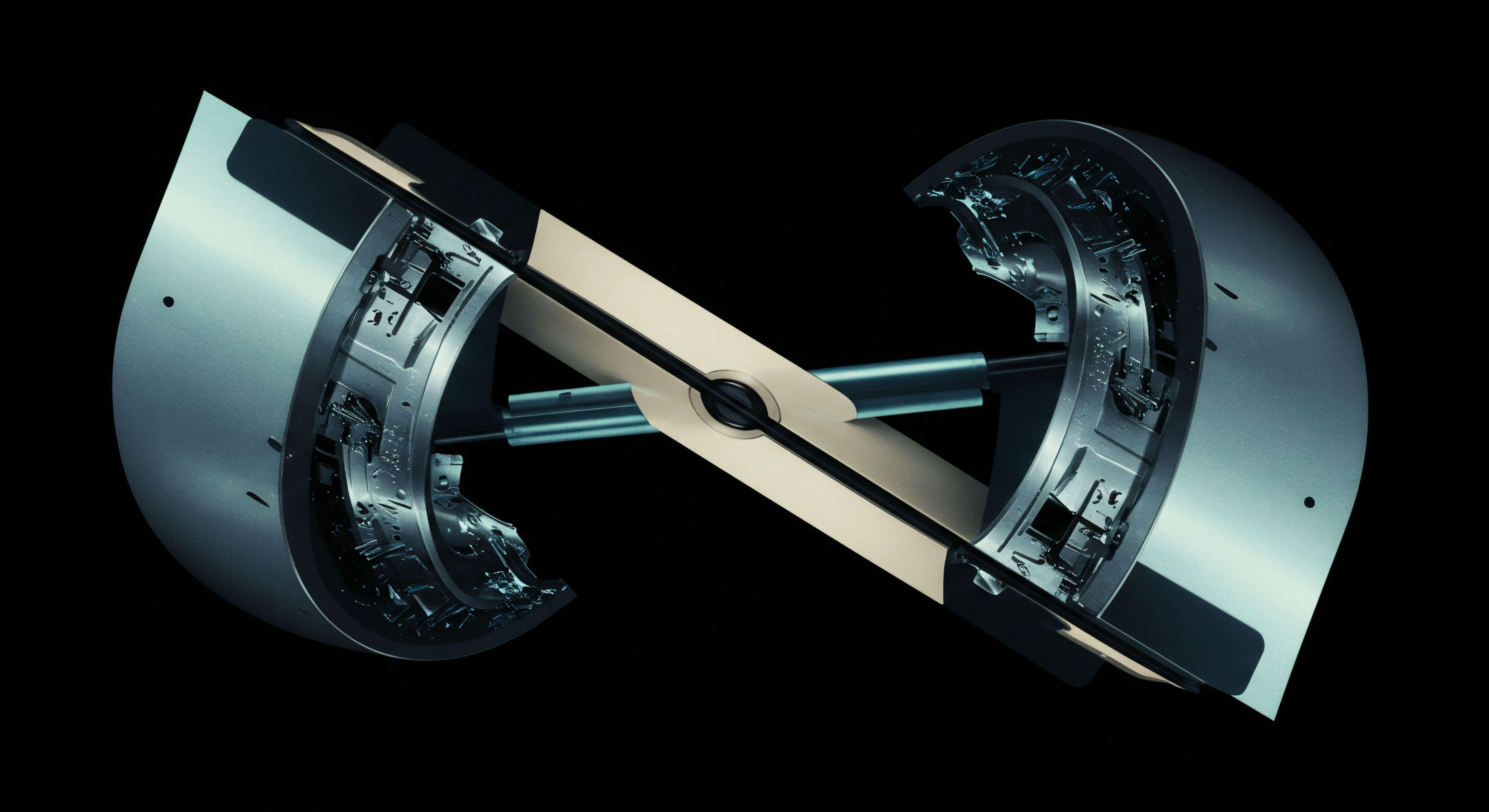

Conversely, a CCP introduces a fundamental change in the structure of risk. The CCP becomes the counterparty to every trade, a process known as novation. It stands between the original buyer and seller, guaranteeing performance to both. This action transforms a complex web of bilateral exposures into a hub-and-spoke model.

Every market participant’s risk is now concentrated on the CCP itself. The CCP mitigates this concentrated risk through a multi-layered defense system ▴ collecting initial and variation margin from all participants, maintaining a default fund, and enforcing rigorous membership standards. The risk is no longer a direct, bilateral concern but a shared, systemic one. The stability of the entire market segment comes to depend on the robustness of the CCP’s risk management framework. This shift from a decentralized network of private obligations to a centralized guarantor of performance is the principal distinction in how these two models address counterparty risk.

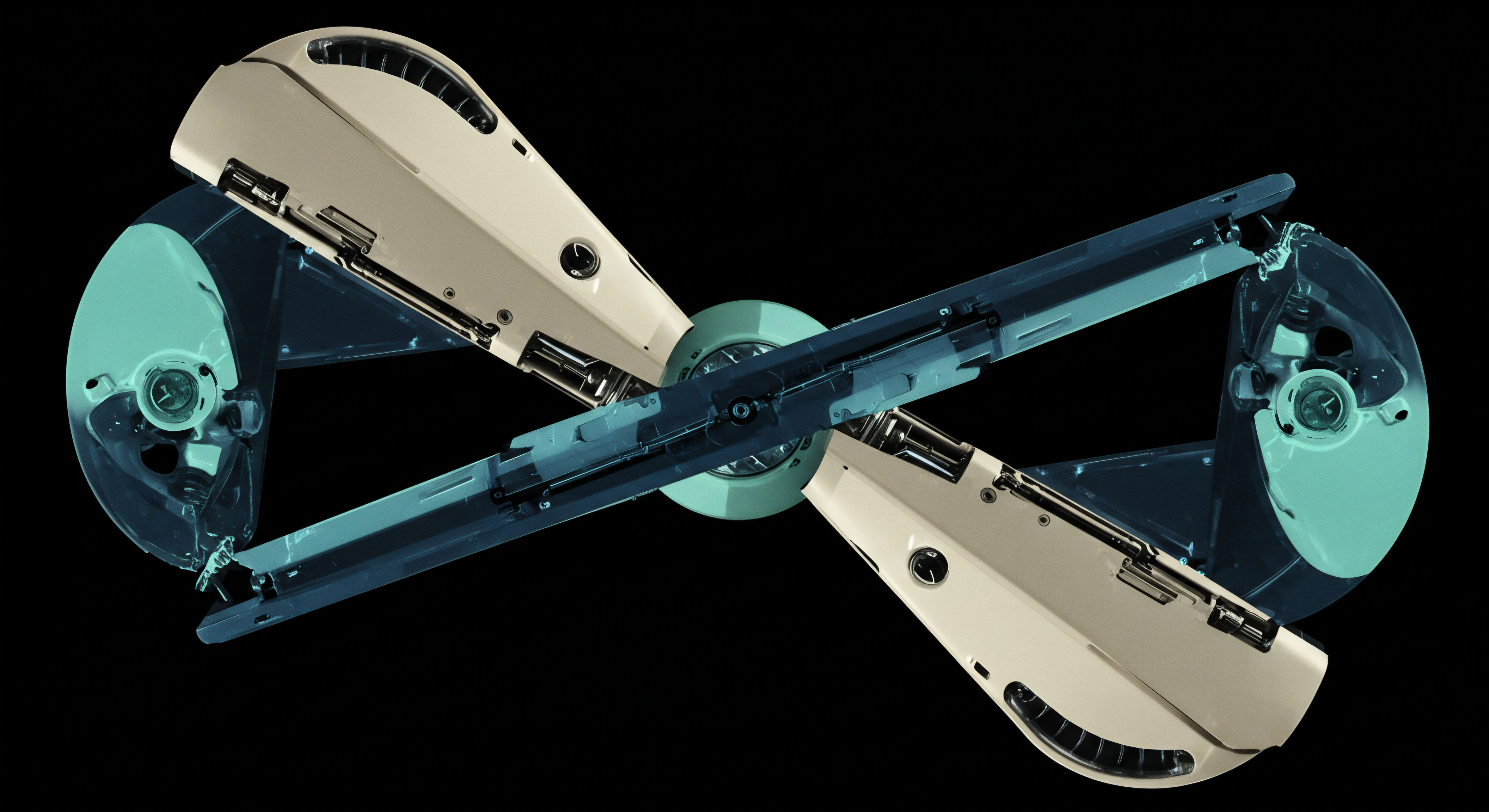

Strategy

The Calculus of Risk Allocation

The strategic decision to utilize a bilateral RFQ framework or a centrally cleared model is a function of an institution’s specific objectives regarding capital efficiency, operational autonomy, and the nature of the desired transaction. These are not merely different paths to execution; they are distinct operational strategies with profound implications for how risk is measured, managed, and capitalized. The choice reflects a firm’s core philosophy on assuming and mitigating financial exposures.

An RFQ-based strategy offers maximum discretion and customization. It is particularly effective for large, complex, or illiquid trades where price discovery is sensitive and anonymity is paramount. In this model, an institution leverages its own creditworthiness and its network of dealer relationships to secure favorable terms. The strategic advantage lies in the ability to negotiate bespoke collateral agreements or even trade on an uncollateralized basis with trusted counterparties.

This can significantly enhance capital efficiency for firms with strong credit standing. The risk management strategy is surgical, focused on intensive counterparty due diligence and the legal strength of bilateral agreements. The trade-off for this flexibility is the direct assumption of counterparty default risk and the operational burden of managing multiple bilateral relationships, each with its own legal and collateralization nuances.

Netting Efficiency and Its Systemic Impact

A critical strategic consideration is the concept of netting. In a bilateral RFQ world, netting occurs only between two specific counterparties across all their mutual trades. If Institution A has multiple offsetting positions with Dealer B, these can be netted to reduce the total exposure. This bilateral netting is highly efficient for that specific relationship.

However, Institution A’s exposure to Dealer C remains entirely separate. The system’s overall efficiency is limited by the number of overlapping trades between any two parties.

Central clearing introduces multilateral netting, which fundamentally alters the efficiency equation. The CCP nets a participant’s positions across all other members of the clearing house for a specific asset class. This can dramatically reduce the total notional exposure and, consequently, the amount of required margin. The strategic cost of this efficiency is the loss of cross-asset class netting opportunities that might exist in a bilateral relationship.

For instance, a dealer might have offsetting positions in interest rate swaps and credit default swaps with another dealer. In a bilateral world, these can be netted. If these asset classes are cleared through two separate CCPs, this netting benefit is lost. Therefore, the strategic choice involves weighing the powerful multilateral netting benefits within a single asset class against the potential loss of bilateral netting benefits across multiple asset classes.

The strategic selection between RFQ and CCP hinges on a trade-off between the customized, capital-efficient nature of bilateral agreements and the systemic risk reduction offered by a mutualized default fund.

The following table outlines the strategic trade-offs inherent in each model:

| Strategic Factor | RFQ (Bilateral) Framework | CCP (Central Clearing) Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Management Focus | Individual counterparty credit analysis; negotiation of ISDA/CSA agreements. | Standardized margin methodologies; contribution to a mutualized default fund. |

| Capital Efficiency | Potentially high, based on bespoke collateral terms or uncollateralized trading with trusted partners. | Driven by multilateral netting efficiency; mandatory initial and variation margin posting. |

| Operational Complexity | High overhead for managing multiple bilateral relationships and collateral agreements. | Streamlined through a single connection to the CCP, but requires adherence to rigid operational protocols. |

| Privacy and Anonymity | High degree of privacy in price discovery and execution. | Trade details are reported to the CCP, reducing anonymity compared to direct negotiation. |

| Suitability | Large, illiquid, or complex multi-leg trades requiring bespoke terms. | Standardized, liquid instruments where systemic risk reduction is prioritized. |

The Role of Collateral and Margining

The strategic approach to collateralization differs fundamentally between the two systems. In the RFQ model, collateral is a negotiated term documented in a Credit Support Annex (CSA). This allows for significant flexibility.

Parties can agree on the types of eligible collateral (cash, government bonds), the thresholds at which collateral must be posted, and the frequency of valuation. For highly-rated institutions, this can result in very favorable, capital-efficient terms.

In the CCP model, collateralization is a rigid, non-negotiable, and core component of the risk mitigation system.

- Initial Margin ▴ This is a good-faith deposit, calculated by the CCP using complex models like VaR (Value-at-Risk), to cover potential future losses in the event of a member’s default. It is the clearing member’s contribution to the CCP’s resilience.

- Variation Margin ▴ This is exchanged daily (or more frequently) to settle the mark-to-market changes in the value of open positions. It prevents the accumulation of large unrealized losses.

- Default Fund ▴ This is a mutualized fund, contributed to by all clearing members, designed to absorb losses that exceed a defaulted member’s posted initial margin. It represents the collectivization of risk.

The strategic implication is a shift from customized, relationship-based collateral terms to a standardized, system-based approach. While this increases transparency and predictability, it also imposes a more rigid and often higher baseline cost of capital for maintaining positions. The choice is between the bespoke efficiency of bilateral agreements and the systemic security of a standardized, multi-layered defense mechanism.

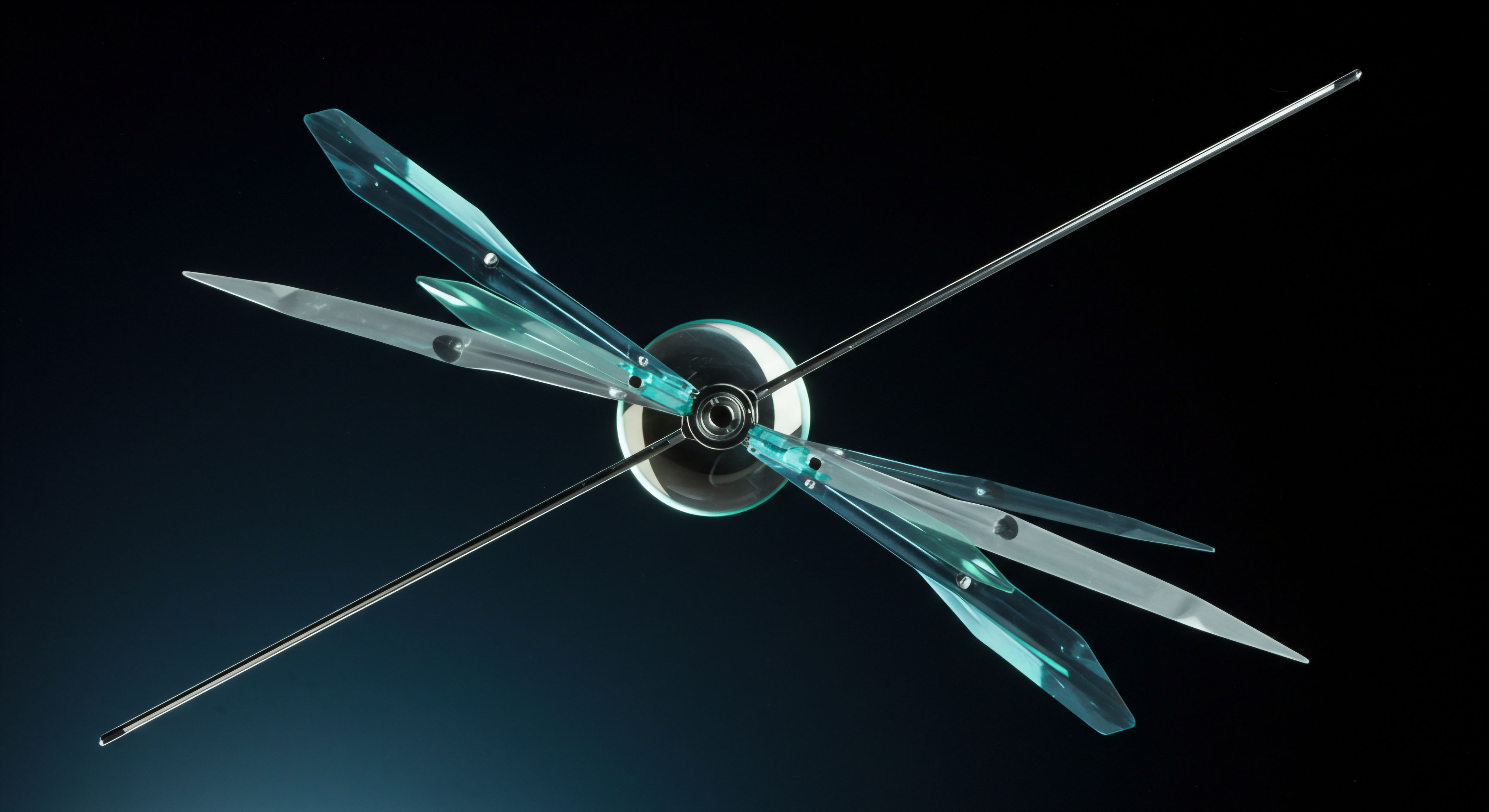

Execution

The Mechanics of Bilateral Default

The execution of a trade within an RFQ framework culminates in a bilateral contract, and the management of a potential default is governed entirely by the terms of that private agreement. The process is precise, legalistic, and contingent upon the actions of the non-defaulting party. There is no central authority to intervene; the resolution is a direct consequence of the pre-negotiated legal architecture.

Upon a default event, such as a failure to make a payment or bankruptcy, the non-defaulting party must take specific procedural steps as outlined in the ISDA Master Agreement.

- Termination Notice ▴ The non-defaulting party issues a formal notice to the defaulting party, designating an Early Termination Date for all outstanding transactions covered under the agreement.

- Valuation of Positions ▴ The non-defaulting party calculates the market value of all terminated transactions. This process, known as “Close-out Amount,” determines the replacement cost or gain for the entire portfolio of trades.

- Netting and Final Payment ▴ All positive and negative values are netted into a single, final figure. If the net amount is owed to the non-defaulting party, it becomes a claim against the defaulting party’s estate. If the amount is owed to the defaulting party, the non-defaulting party makes that payment. The execution risk lies in the potential for disputes over the valuation of positions and the ultimate recovery rate on any claims made in bankruptcy proceedings.

This entire process is self-managed. The operational burden and legal costs fall entirely on the surviving counterparty. The success of the execution depends on the clarity of the legal agreement and the firm’s operational capacity to manage the close-out process efficiently.

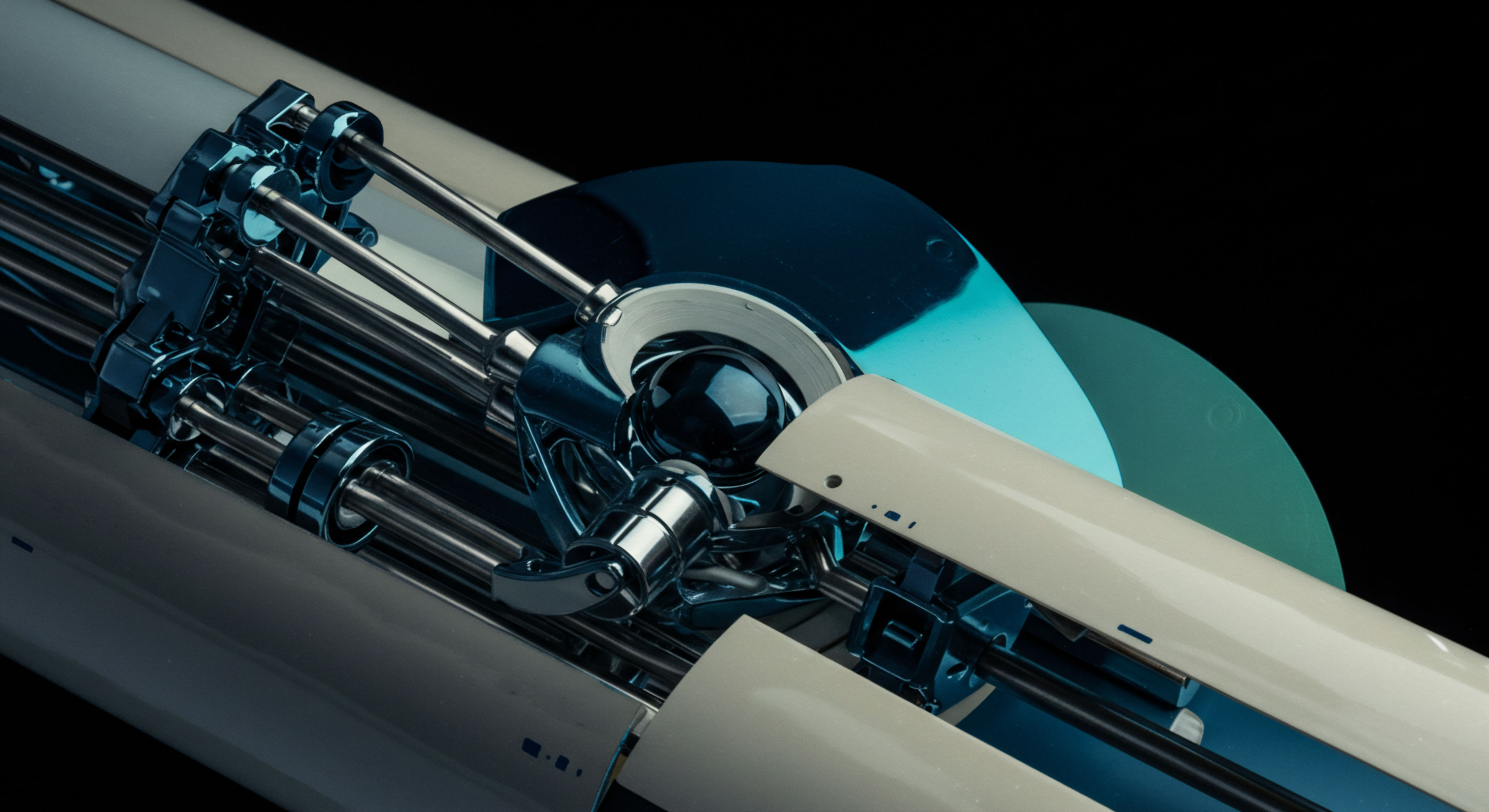

The CCP Default Waterfall

Central clearing fundamentally re-architects the default management process into a sequential, multi-layered system known as the “default waterfall.” The execution is systematic, predetermined, and managed by the CCP. The objective is to insulate the non-defaulting members from the failure of a single participant and maintain the stability of the broader market. The process is designed to be swift and predictable, minimizing contagion risk.

The following table details the typical layers of a CCP’s default waterfall, executed in sequence:

| Layer | Description | Source of Funds |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Defaulter’s Margin | The CCP immediately seizes the initial and variation margin posted by the defaulting member. This is the first line of defense. | Defaulting Member’s own capital. |

| 2. Defaulter’s Default Fund Contribution | The CCP utilizes the defaulting member’s contribution to the mutualized default fund. | Defaulting Member’s contribution to the shared pool. |

| 3. CCP’s Own Capital | A portion of the CCP’s own capital (often called “skin-in-the-game”) is used to cover further losses. This aligns the CCP’s interests with its members. | CCP’s corporate capital. |

| 4. Survivors’ Default Fund Contributions | The CCP draws upon the default fund contributions of the non-defaulting members on a pro-rata basis. This is the mutualization of the loss. | Non-Defaulting Members’ capital. |

| 5. Further Assessments (Cash Calls) | If losses are still not covered, the CCP may have the right to levy additional assessments on the surviving members, up to a pre-agreed limit. | Additional capital from Non-Defaulting Members. |

Executing a close-out in a bilateral RFQ world is a private legal procedure, whereas managing a default in a CCP environment is a pre-defined, systemic process designed to mutualize and absorb losses.

The execution of this waterfall is a highly structured process. The CCP’s primary goal is to hedge or auction off the defaulting member’s portfolio to other members to neutralize the market risk. Any losses incurred during this process are then covered by working down the layers of the waterfall. The key operational difference is the removal of the individual firm from the messy business of default management.

The process is handled by a specialized, regulated entity with a clear, transparent, and pre-agreed-upon playbook. The risk for a non-defaulting member is transformed from the full, direct loss of a bilateral default into a known, capped exposure to the mutualized default fund.

References

- Duffie, Darrell, and Haoxiang Zhu. “Does a central clearing counterparty reduce counterparty risk?.” The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2011, pp. 74-95.

- Cont, Rama, and Amal Moussa. “The FVA debate.” Risk Magazine, 2014.

- Pirrong, Craig. “The economics of central clearing ▴ theory and practice.” ISDA Discussion Papers Series, no. 1, 2011.

- Norman, Peter. The Risk Controllers ▴ Central Counterparty Clearing in Globalised Financial Markets. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Gregory, Jon. Central Counterparties ▴ Mandatory Clearing and Bilateral Margin Requirements for OTC Derivatives. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- Hull, John C. Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives. 11th ed. Pearson, 2021.

- Cecchetti, Stephen G. et al. “Central counterparties for over-the-counter derivatives.” BIS Quarterly Review, September 2009.

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association. “ISDA Master Agreement.” ISDA, 2002.

Reflection

Calibrating the Risk Engine

The analysis of counterparty risk within RFQ and CCP frameworks provides more than a comparative overview; it offers a schematic for calibrating a firm’s own internal risk engine. The selection of an execution model is an architectural choice that defines the nature of the liabilities a firm is willing to assume. It compels an institution to look inward and assess its own structural capacity for risk management.

Does the operational framework possess the legal and analytical horsepower to manage a portfolio of discrete, bilateral risks? Or is its strength in standardized process adherence and capital allocation against a systemic, mutualized backstop?

Viewing these models as components within a larger operational system reveals their true function. They are not simply venues for execution but integral parts of a firm’s strategy for capital preservation and deployment. The knowledge of their distinct mechanics allows for a more deliberate and sophisticated approach to trading.

An institution can then dynamically allocate flow between these two systems, not as a matter of simple preference, but as a calculated decision based on the specific risk signature of a trade, the firm’s current capital position, and its overarching strategic objectives. The ultimate advantage is found in the ability to see the market not as a monolithic entity, but as a system of interconnected architectures, each to be used with precision and purpose.

Glossary

Central Counterparty Clearing

Counterparty Risk

Isda Master Agreement

Variation Margin

Risk Management

Managing Multiple Bilateral Relationships

Multilateral Netting

Central Clearing

Initial Margin

Default Fund

Non-Defaulting Party

Master Agreement

Non-Defaulting Members

Default Waterfall