Concept

The intellectual property clause within a software development Request for Proposal (RFP) represents the nucleus of value in the transaction. It is the architectural schematic that dictates not merely ownership, but the operational authority, strategic optionality, and future enterprise value of the resulting digital asset. The negotiation of this clause is a primary determinant of the system’s long-term viability.

It establishes the fundamental allocation of rights between the commissioning entity, which seeks maximum control and return on investment, and the development firm, which must protect its foundational technologies, proprietary tools, and accumulated expertise. This process moves far beyond a simple legal formality; it is a foundational act of corporate strategy.

At its core, the negotiation addresses an inherent structural tension. The client organization is procuring a custom solution to a specific business problem and, quite logically, expects to own the result of its investment. The development partner, conversely, builds its competitive advantage and operational efficiency upon a repository of pre-existing code, libraries, frameworks, and proprietary methodologies. This “background IP” is the firm’s capital.

Forcing a complete transfer of this foundational technology in every engagement would be economically untenable for the developer, akin to a master craftsman selling his entire workshop with each commissioned piece. The negotiation, therefore, is the mechanism for resolving this tension, defining a clear demarcation between the newly created asset and the tools used to build it.

Understanding the distinction between bespoke code created for the project and the developer’s pre-existing intellectual property is the foundational insight for any successful IP clause negotiation.

The primary forms of intellectual property at play are precise and distinct. Copyright is the most immediate, granting ownership over the literal expression of the source code. Patents may protect novel algorithms or processes embedded within the software, offering a powerful, albeit less common, form of monopoly. Trade secrets protect the developer’s confidential methods, techniques, and know-how that provide a competitive edge.

The dialogue around the IP clause is an exercise in allocating these rights with surgical precision. A successful outcome is one where the final agreement is perfectly aligned with the client’s specific business objectives, whether that be unrestricted commercialization, internal operational use, or future modification, while preserving the developer’s ability to operate and innovate.

The Anatomy of an IP Clause

An IP clause is not a monolithic block but a composite of several distinct, negotiable components. Each component addresses a specific facet of the rights allocation, and understanding their interplay is essential for a strategic negotiation. The primary elements establish the baseline of control and usage rights for the developed software system.

- Ownership of Deliverables This component specifies who owns the custom software, documentation, and other materials created specifically for the client under the agreement. The default client position is to demand full ownership via a “work made for hire” stipulation or an express assignment of rights.

- Licensing of Pre-Existing IP This is arguably the most critical and nuanced area of negotiation. The developer must grant the client a license to use any of its background IP that is incorporated into the final product. The terms of this license (e.g. perpetual, royalty-free, non-exclusive) are key negotiation points.

- Treatment of Third-Party and Open Source Software Modern software is rarely built from scratch. This part of the clause must account for any third-party components, especially open source software, and ensure compliance with their respective licenses. It allocates the risk associated with these external dependencies.

- Warranties and Indemnification Here, the developer provides assurances that the work is original and does not infringe upon the IP rights of a third party. The indemnification provision obligates the developer to defend and compensate the client if an infringement claim arises.

Effectively navigating these components requires a shift in perspective. The goal is the creation of a balanced system that grants the client the necessary operational freedom while respecting the developer’s legitimate interest in its core assets. The negotiation is the process of calibrating this system for mutual, long-term success.

Strategy

A strategic approach to negotiating the IP clause transforms the process from a contentious, zero-sum battle to a sophisticated exercise in value engineering and risk allocation. The objective is to construct a contractual framework that is resilient, flexible, and precisely aligned with the intended lifecycle of the software. This requires a deep understanding of the strategic levers available to both parties and the long-term consequences of the choices made. The negotiation strategy is not about winning points; it is about designing a durable economic and operational partnership.

The central strategic decision revolves around the ownership model. This choice radiates through the entire agreement, influencing cost, flexibility, and the very nature of the client-vendor relationship. The spectrum of options ranges from complete ownership by the client to complete ownership by the developer, with the client receiving a license. Each model presents a different profile of benefits and trade-offs.

A full assignment of all IP to the client, for instance, provides maximum control and eliminates vendor dependency, but it typically comes at a significant price premium and may be unacceptable to developers with highly valuable background IP. Conversely, a license model can reduce upfront costs and leverage the developer’s expertise, but it requires careful structuring to ensure the client has the rights it needs for future development and maintenance.

Core Negotiation Points and Their Strategic Implications

Beyond the high-level ownership model, several specific points within the IP clause serve as critical arenas for negotiation. Mastering these points allows an organization to tailor the agreement to its precise strategic requirements.

Ownership and Licensing of the Core Asset

The default position for most clients is to seek full and unencumbered ownership of the custom code they commission. This is often framed as a “work made for hire” relationship or includes a clause of express assignment. Developers, particularly those with a specialized product or platform, will counter by proposing they retain ownership of the code while granting the client a broad license. The strategic compromise often involves carefully defining what constitutes “Foreground IP” (the custom code) versus “Background IP” (the developer’s pre-existing tools and frameworks).

The client may secure full ownership of the Foreground IP, while receiving a perpetual, royalty-free, irrevocable, and worldwide license to the Background IP as it is incorporated into the final deliverable. This structure gives the client the control it needs over the custom asset without forcing the developer to part with its core technology.

The distinction between foreground IP created for the client and background IP belonging to the developer is the central pivot point of the entire negotiation.

The following table compares the strategic implications of the two primary ownership models:

| Consideration | Client Ownership Model (Assignment/Work for Hire) | Developer Ownership Model (License to Client) |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Control | Maximum. Client has complete freedom to modify, sell, or re-license the software. | Limited by the scope of the license. Restrictions may apply to modification, transfer, or commercialization. |

| Upfront Cost | Higher. The price reflects the full transfer of all future value and optionality. | Lower. The client is paying for use rights, not the underlying asset itself. |

| Vendor Dependency | Low. Client can engage any other vendor for future maintenance or development. | High. The client is tied to the original developer for support, updates, and potentially future modules. |

| Access to Innovation | Static. The client owns a snapshot of the code at the time of delivery. | Potentially higher. The client may benefit from ongoing platform-level improvements made by the developer. |

| Negotiation Complexity | Lower. The terms are straightforward, focusing on a clean transfer. | Higher. The license scope, usage rights, and restrictions require detailed negotiation. |

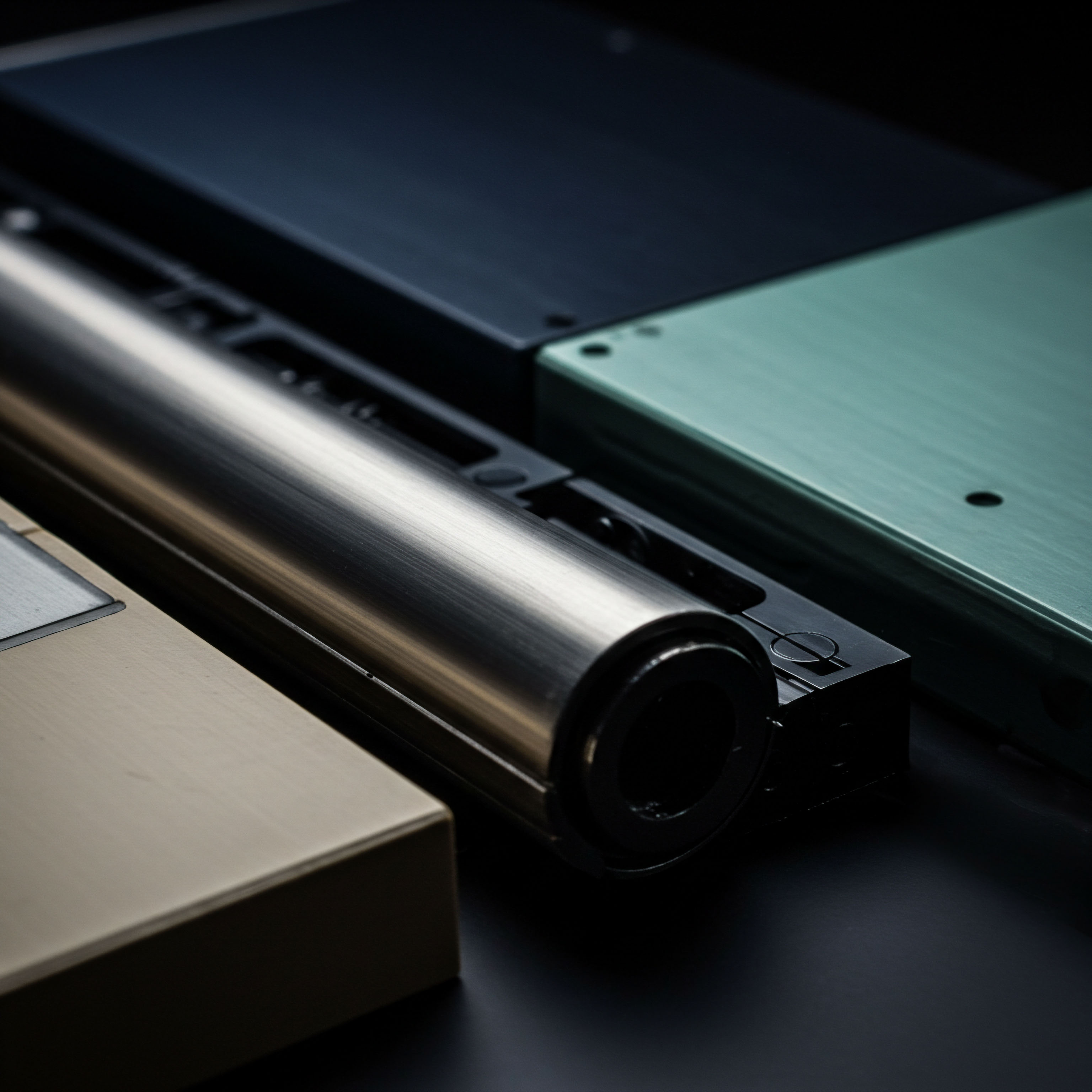

The Treatment of Open Source Software

The use of open source software (OSS) is ubiquitous in modern development, but it introduces significant complexity into IP negotiations. The core strategic challenge is to ensure that the inclusion of OSS components does not compromise the client’s ownership of its proprietary code or create unintended obligations. The negotiation must focus on warranties from the developer regarding the OSS used and clear identification of all OSS licenses.

There are two main categories of OSS licenses, and their strategic implications are vastly different:

- Permissive Licenses (e.g. MIT, Apache 2.0, BSD) ▴ These licenses impose minimal restrictions. They allow the OSS code to be modified and incorporated into proprietary, closed-source commercial products. From a strategic perspective, these are generally safe for most commercial applications, requiring little more than attribution.

- Copyleft Licenses (e.g. GNU General Public License – GPL) ▴ These licenses are “viral.” They require that any derivative work that incorporates copyleft-licensed code must itself be licensed under the same copyleft terms. This can force a company to release its own proprietary source code to the public, destroying its commercial value. Strong copyleft (GPL) applies to any derivative work, while weak copyleft (LGPL) is triggered only by direct modification of the library itself, not by simply linking to it. The negotiation must include a strong warranty from the developer that no strong copyleft licensed code has been used in a way that would “infect” the client’s proprietary code.

Indemnification and Liability

The IP indemnification clause is a critical risk-transfer mechanism. Through this clause, the developer takes on the responsibility to defend the client against any third-party claims that the developed software infringes on their intellectual property. Strategic negotiation points include ▴

- The Scope of Indemnity ▴ Does it cover all IP rights, including patents, copyrights, and trade secrets?

- The Indemnification Cap ▴ Developers will often try to cap their liability at the total value of the contract. Clients should push for a higher cap or, ideally, an uncapped indemnity for IP infringement, arguing that the potential damages from an infringement suit could far exceed the project’s cost.

- Control of Defense ▴ The clause will specify who controls the legal defense in case of a claim. Typically, the indemnifying party (the developer) wants control, but the client should negotiate for the right to approve the legal counsel and any settlement offers.

Execution

The execution phase of an IP clause negotiation requires a disciplined, systematic approach that translates strategic goals into precise, enforceable contract language. This is where high-level objectives are operationalized through detailed checklists, quantitative analysis, and a clear understanding of the technical and legal mechanics. Success is predicated on rigorous preparation and a clear-eyed assessment of the economic and operational realities underpinning the agreement.

The Operational Playbook

A structured playbook ensures that both parties enter the negotiation with a complete understanding of their objectives, constraints, and non-negotiable positions. This systematic preparation prevents critical oversights and aligns the legal negotiation with the business reality.

Client Pre-Negotiation Checklist

- Define Future Use Cases ▴ Articulate, with precision, all potential future uses for the software. Will it be commercialized? Integrated with other systems? Sold as part of a corporate acquisition? The answers directly inform the necessary scope of IP rights.

- Conduct an Internal IP Audit ▴ Identify any client-owned IP (e.g. proprietary data, existing code) that will be provided to the developer. Ensure this is clearly defined and excluded from any IP transfer to the developer.

- Establish the Business Case for Ownership ▴ Quantify the value of owning the IP versus licensing it. This analysis should inform the budget and the client’s willingness to pay a premium for full ownership.

- Mandate an Open Source Scan ▴ Require, in the RFP and the contract, that the developer use a third-party tool to scan all code for open source components and provide a full report for legal review before final acceptance.

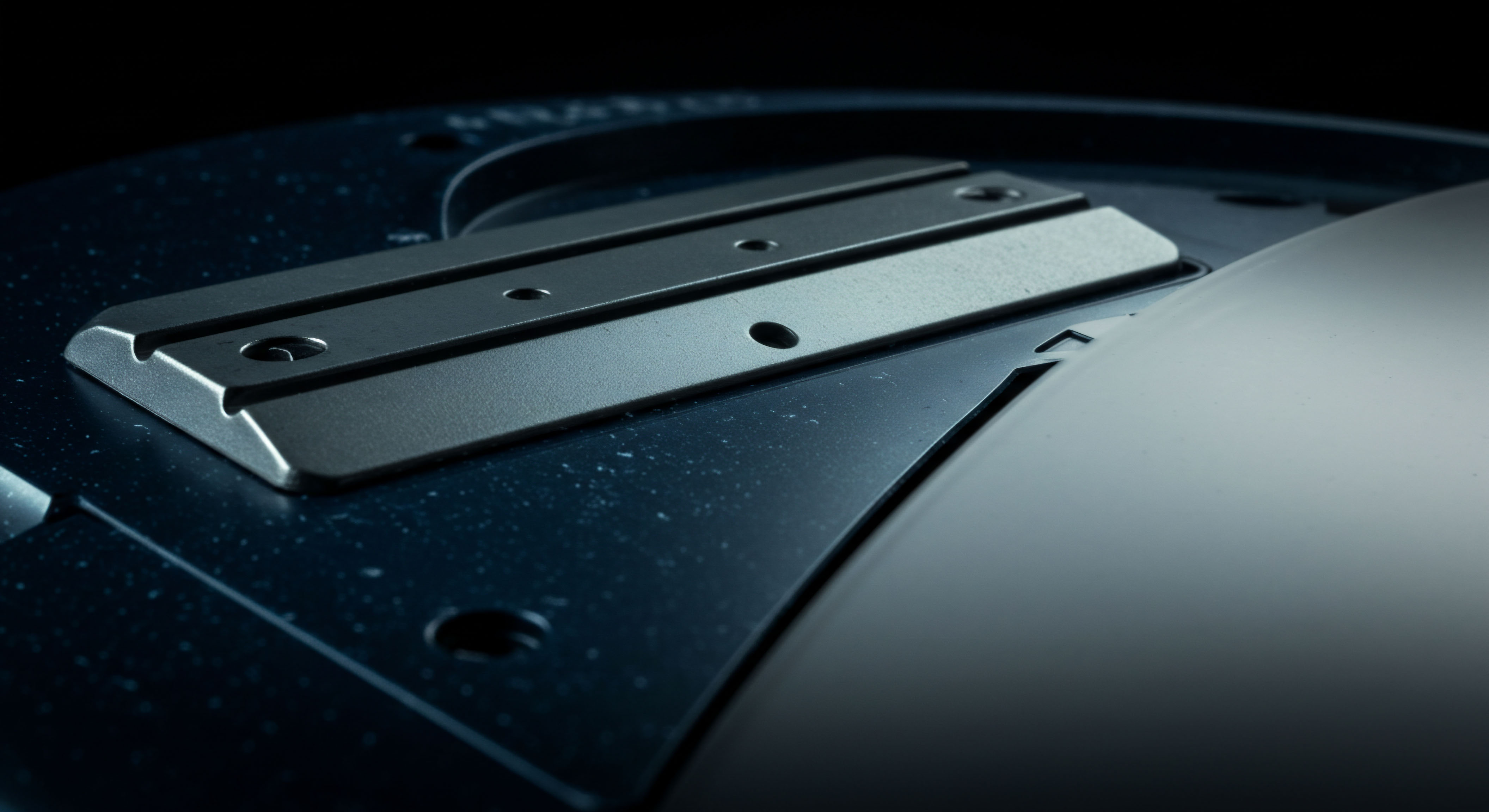

- Plan for Vendor Failure ▴ Insist on a source code escrow agreement for mission-critical software, especially when the developer retains ownership. This ensures access to the source code if the developer goes out of business or fails to meet support obligations.

Developer Pre-Negotiation Checklist

- Document All Background IP ▴ Create a definitive, version-controlled list of all pre-existing code, libraries, frameworks, and tools that may be used in the project. This list should be an appendix to the contract.

- Establish a Clear IP Policy ▴ Maintain a firm, consistent internal policy on what IP the company will and will not assign to clients. This prevents ad-hoc decisions and strengthens the negotiating position.

- Vet All Third-Party Components ▴ Before incorporating any third-party or open source code, ensure its license is fully understood and compatible with the project’s IP model. Maintain a comprehensive bill of materials for all software components.

- Define the Scope of the License Grant ▴ If the developer is retaining ownership, draft a clear, comprehensive license grant that provides the client with all necessary rights for their stated business purpose, while retaining all other rights for the developer.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

Decisions in an IP negotiation should be informed by quantitative analysis. Modeling the financial implications of different IP structures provides an objective basis for what might otherwise be a purely qualitative debate.

A quantitative framework removes subjectivity, allowing both parties to evaluate the long-term financial impact of their IP-related decisions.

Table ▴ Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Model Comparison (5-Year Horizon)

This model compares the financial outlay for a custom software project under two different IP regimes. The Client Ownership model assumes a higher one-time development cost to buy out the IP, while the License Model has a lower initial cost but includes annual licensing/maintenance fees.

| Cost Component | Client Ownership Model | Developer Ownership (License) Model | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Development Cost | $750,000 | $400,000 | The premium for full IP assignment is $350,000. |

| Annual Maintenance/Support (Year 1) | $112,500 (15% of initial cost) | $0 (Included in license) | Maintenance is often a percentage of the initial development cost. |

| Annual License Fee (Years 2-5) | $0 | $100,000 | A recurring fee for the right to use the developer-owned platform. |

| Annual Maintenance/Support (Years 2-5) | $450,000 (4 x $112,500) | $0 (Included in license) | Assumes a constant maintenance fee. |

| Total 5-Year TCO | $1,312,500 | $800,000 | The license model is significantly cheaper over five years. |

| Terminal Value | High (Asset can be sold) | Zero (License has no resale value) | The client must weigh the lower TCO against the lack of a saleable asset. |

Predictive Scenario Analysis

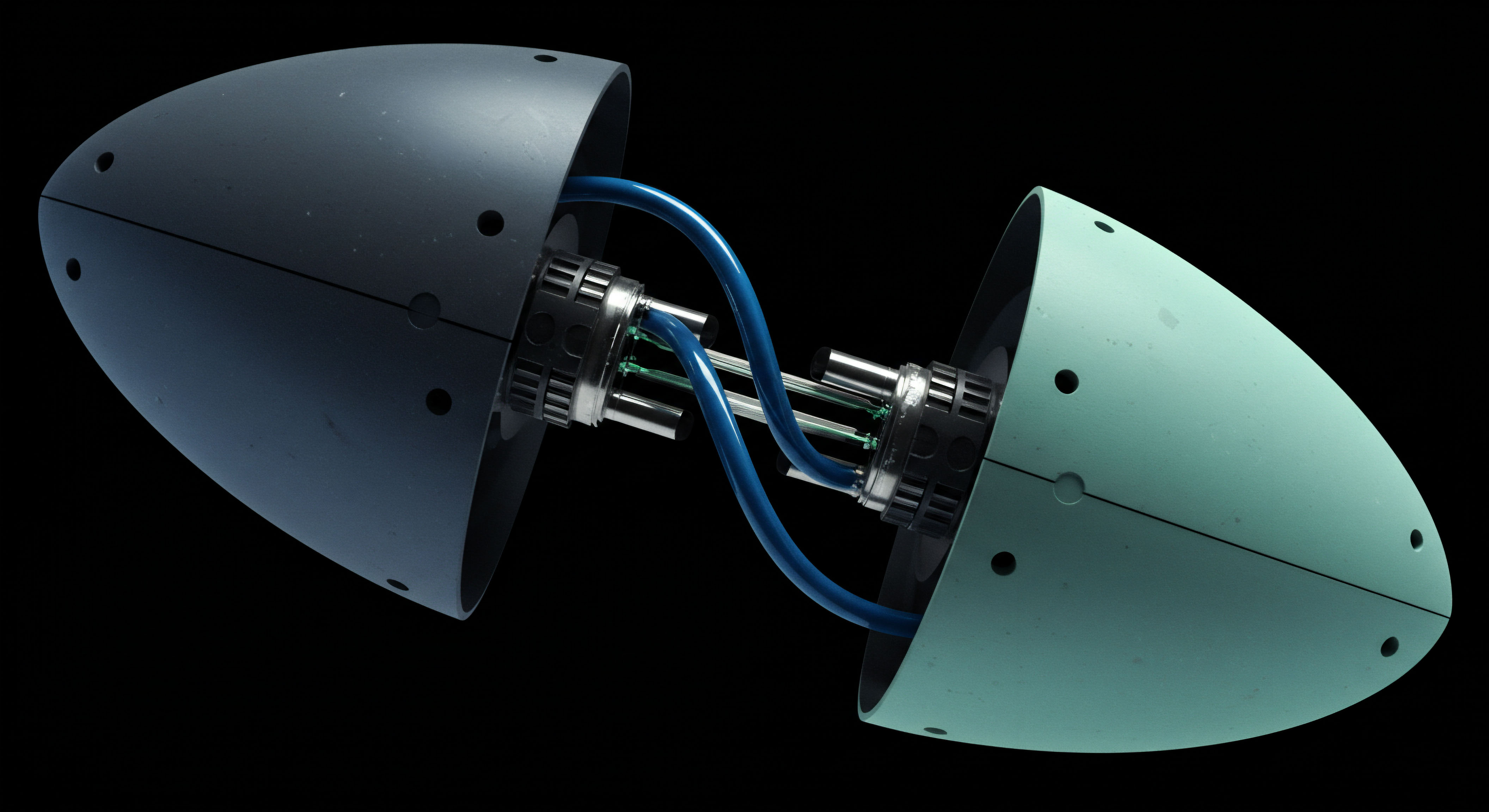

A narrative case study can illuminate the practical application of these principles. Consider the negotiation between “AutoFleet,” a regional vehicle fleet management company, and “LogiCore,” a specialized software development firm, for a new logistics and dispatching platform.

AutoFleet’s RFP demands full ownership of all developed software. LogiCore counters, explaining that their proposal is based on their existing “LogiCore Platform,” a sophisticated collection of pre-existing modules for routing, scheduling, and analytics. Assigning ownership of this platform to AutoFleet is not feasible. The negotiation shifts from a simple ownership demand to a more nuanced discussion.

The parties agree to define the “Foreground IP” as the custom user interfaces, workflows, and specific business rule implementations created for AutoFleet. AutoFleet will own this Foreground IP. The “Background IP” is defined as the core LogiCore Platform. LogiCore will retain ownership of the Background IP but will grant AutoFleet a perpetual, royalty-free, irrevocable license to use it as an integrated part of the delivered system. This satisfies AutoFleet’s need for control over the custom elements while protecting LogiCore’s core asset.

During due diligence, AutoFleet’s legal team flags a potential issue. A junior developer at LogiCore used an open-source charting library licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL) for a non-critical dashboard feature. Because the GPL is a “viral” copyleft license, its use could potentially require AutoFleet to make their entire proprietary platform open source if they distribute it. The negotiation pauses.

LogiCore, bound by its warranty against using restrictive licenses, agrees at its own cost to replace the GPL-licensed library with a commercially licensed alternative that has no copyleft provisions. The crisis is averted due to a well-drafted warranty clause and a diligent review process.

Finally, the parties address the issue of long-term viability. What if LogiCore is acquired by a competitor or goes out of business? To mitigate this risk, they agree to a source code escrow agreement. A neutral third-party escrow agent will hold a copy of the LogiCore Platform’s source code.

The escrow agreement specifies “release conditions,” such as the bankruptcy of LogiCore or a material, uncured breach of the support agreement. If a release condition is met, the source code will be released to AutoFleet, giving them the ability to maintain and modify the system themselves or with another vendor. This provides AutoFleet with the ultimate safety net, making them comfortable with LogiCore retaining ownership of the Background IP.

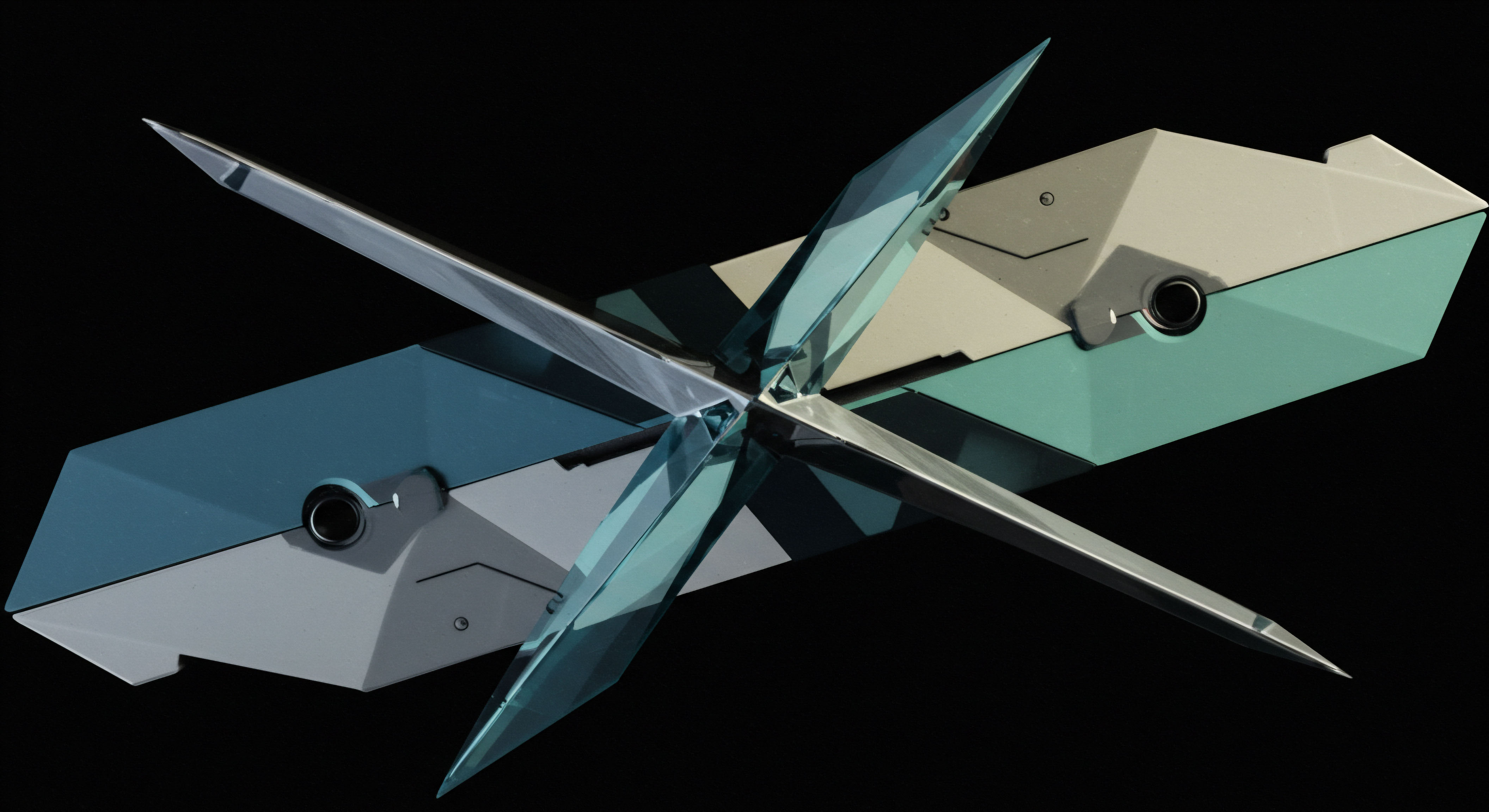

System Integration and Technological Architecture

The IP clause has direct and significant consequences for the system’s technical architecture and future integration capabilities. The ownership and licensing of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), for example, are of paramount importance. If the developer retains ownership of the APIs and licenses them restrictively, the client may be unable to integrate the new system with other enterprise software or build new applications on top of it. The contract must explicitly grant the client broad rights to use, and allow third parties to use, the system’s APIs for integration purposes.

A technical due diligence process is also a critical part of executing the IP strategy. This involves more than just a legal review of license names. It requires automated code scanning tools that can identify the “fingerprints” of known open source libraries, even if they have been modified or copied without their license files. This technical verification is the only reliable way to enforce the developer’s open source warranties and prevent unintended license contamination.

References

- Hall, Aaron. “Conflicts Over Source Code Ownership in Joint Projects.” Attorney Aaron Hall, 2023.

- “Key Considerations for Intellectual Property in Software Development Contracts.” MoldStud, 22 June 2025.

- “A Guide to Contract Negotiation ▴ Navigating Intellectual Property Clauses.” Contract Negotiation Guide, 11 February 2024.

- “Ownership of Source Code in Software Development Agreements.” Oziel Law, 18 April 2013.

- “Best Practices for Contract Negotiation with Software Development Firms.” 1985, 18 December 2024.

- “The Role of Intellectual Property Rights in Software Development Contracts.” Michael Edwards | Commercial Corporate Solicitor.

- “Pre-existing and Independently Developed Intellectual Property Sample Clauses.” Law Insider.

- “Intellectual property basics for startups ▴ open source software.” DLA Piper Accelerate.

- “Open Source Software ▴ Licensing, Compliance, & Intellectual Property Issues.” Ludwig APC, 25 July 2024.

- “Common Negotiation Points in Technology Agreements.” Contract Nerds, 1 August 2023.

Reflection

Ultimately, the intellectual property clause should be viewed as the genetic code of a technology partnership. Its terms dictate the potential, the limitations, and the evolutionary path of the resulting system. Approaching this negotiation not as an adversarial conflict but as a collaborative design process is the hallmark of a mature organization. The objective is to construct a framework that enables both the client and the developer to achieve their core business objectives.

A well-designed IP clause does not produce a winner and a loser. It creates a stable, predictable, and mutually beneficial system that can adapt and deliver value over the long term. The true measure of success is a contract that, once signed, can be filed away, its clarity and foresight preventing future disputes and allowing the parties to focus on the shared goal of building powerful, effective technology.

Glossary

Intellectual Property Clause

Software Development

Background Ip

Intellectual Property

Work Made for Hire

Source Software

Open Source

Ownership Model

Foreground Ip

Ip Indemnification

Source Code Escrow