Concept

A Request for Proposal (RFP) is frequently viewed through the narrow lens of procurement ▴ a mechanism to solicit bids and compare vendor pricing. This perspective, while common, overlooks its most profound function. The RFP is the genesis of a project’s legal and operational architecture; it is the first and most critical opportunity to construct a framework that systematically mitigates owner liability.

Every significant project dispute, from cost overruns to schedule failures and third-party claims, can often be traced back to ambiguities or structural weaknesses embedded in the initial RFP. It is here, before any contract is signed or work begins, that the foundational allocation of risk is established.

Understanding owner liability requires acknowledging the interconnected web of responsibilities inherent in any complex undertaking. The owner is not merely a passive client but an active participant whose actions ▴ or inactions ▴ can create significant legal and financial exposure. This exposure arises from multiple vectors ▴ claims from contractors for delays or unforeseen site conditions, suits from third parties for injury or property damage, and disputes over the finality and quality of the work performed. The RFP, therefore, must be engineered as a comprehensive control system designed to manage these vectors with precision.

The core principle is that a meticulously crafted RFP moves beyond a simple description of needs. It becomes a document of strategic pre-emption. By embedding specific, unambiguous clauses, an owner can define the boundaries of responsibility, mandate essential protections like insurance and indemnification, and establish clear protocols for managing change and resolving disputes.

This process transforms the RFP from a request into a statement of control, setting the terms of engagement in a way that protects the owner’s interests while creating a clear and fair operational environment for the chosen contractor. The clauses within are not mere legal boilerplate; they are the functional components of a sophisticated risk management system.

Strategy

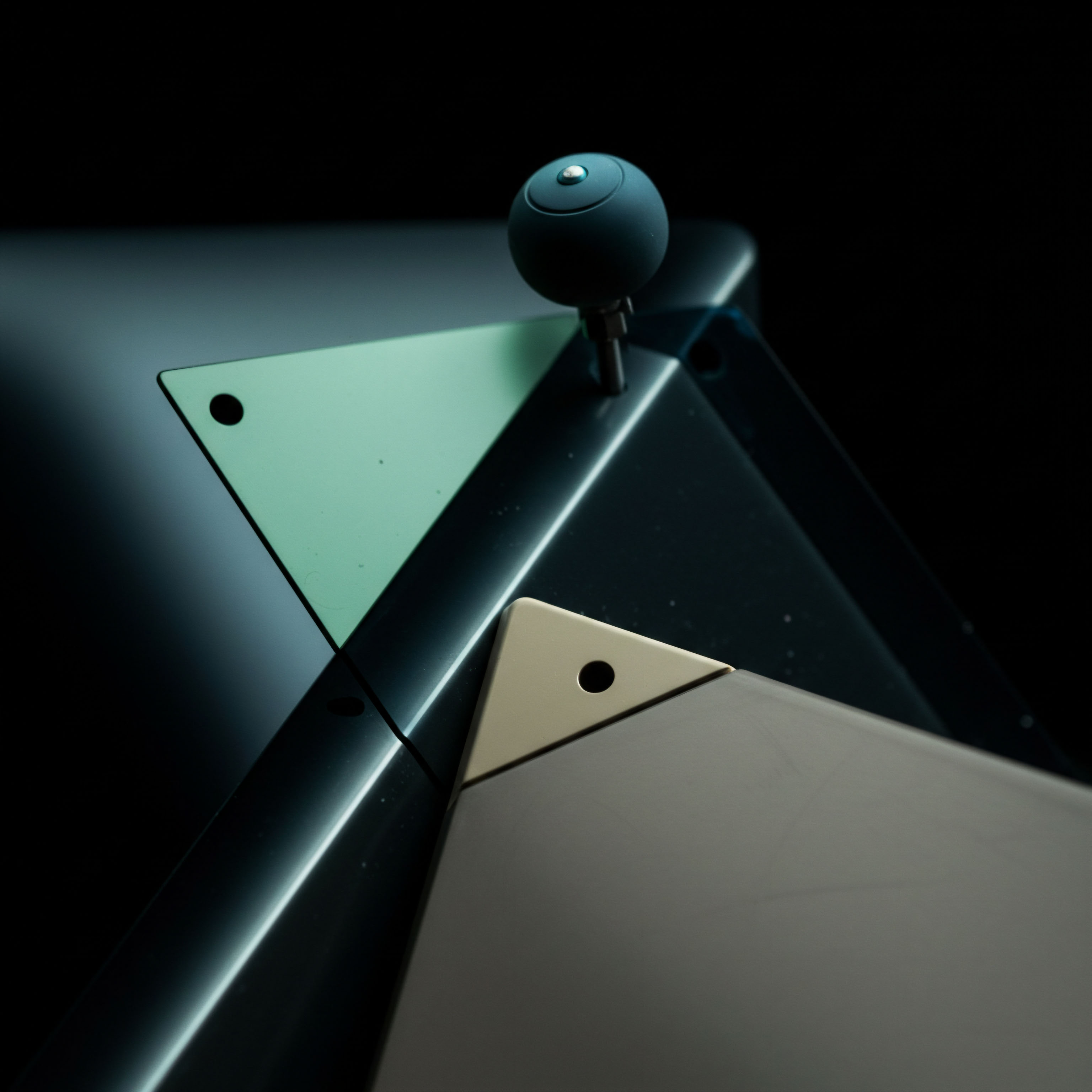

Calibrating the Risk Transfer Apparatus

The strategic design of an RFP’s liability clauses is an exercise in calibrated risk allocation. The fundamental objective is to transfer specific risks to the party best equipped to manage them ▴ typically the contractor ▴ without imposing an untenable or uninsurable burden that inflates bid prices beyond reason. A contractor faced with unlimited or ambiguous liability will price that uncertainty into their proposal, ultimately costing the owner more.

Therefore, the strategy is one of precision, not just complete transference. Key clauses function as the primary mechanisms in this risk transfer apparatus, each calibrated to address a specific type of exposure.

The indemnification clause serves as the central pillar of this strategy. Its purpose is to compel the contractor to cover the owner’s losses arising from the contractor’s actions, particularly in response to third-party claims. However, the strategic calibration lies in defining the scope of this indemnity. A broad-form indemnity, which holds the owner harmless even from their own partial negligence, is often unenforceable in many jurisdictions and signals an overly aggressive posture.

A more strategic approach utilizes an intermediate-form indemnity, which ties the contractor’s obligation directly to their degree of fault. This creates a fair and legally defensible allocation of risk.

A well-defined RFP clause pre-emptively resolves future disputes by establishing clear lines of accountability from the project’s inception.

Complementing indemnification is the strategic use of a Limitation of Liability (LoL) clause. While it may seem counterintuitive for an owner to agree to limit a contractor’s liability, it is a crucial tool for achieving commercial reasonability. An LoL cap, often tied to the contractor’s fee or insurance policy limits, prevents the contractor from facing potentially catastrophic losses on a project.

In exchange for this certainty, the owner receives more competitive pricing and a contractor who is not incentivized to cut corners due to existential financial risk. The waiver of consequential damages ▴ such as lost profits or business interruption ▴ is another strategic component, creating a mutual agreement to exclude unpredictable, high-dollar claims and focus liability on direct, correctable damages.

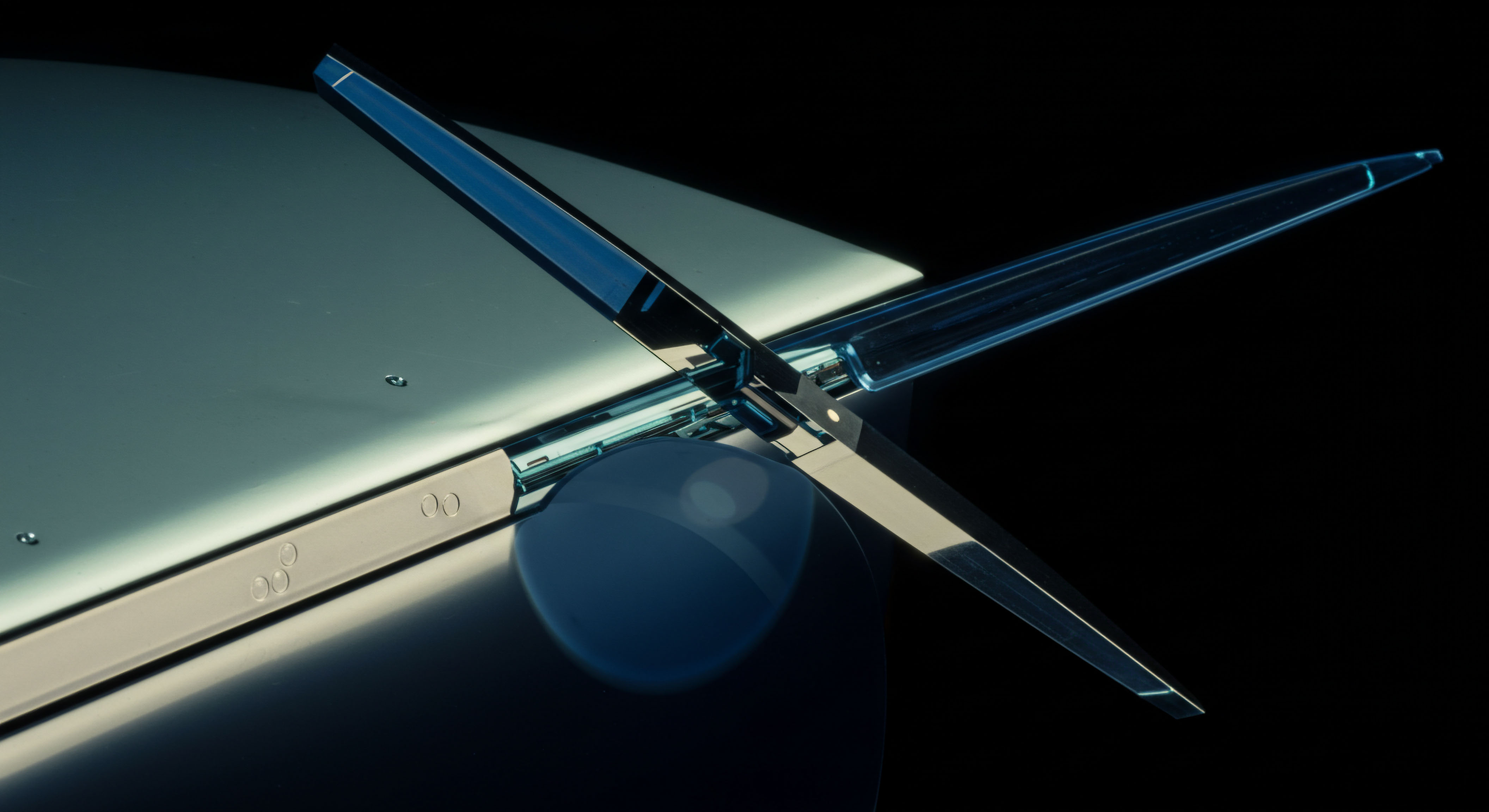

The Triad of Control Scope Price and Time

Owner liability is often triggered by failures in one of three interconnected domains ▴ the scope of work, the project schedule, and the payment structure. An effective RFP strategy addresses these three elements as a unified system, ensuring the clauses governing them are mutually reinforcing. Ambiguity in one area invariably creates risk in the others.

First, the Scope of Work clause must be drafted with surgical precision. It must move beyond a general description to provide a granular definition of all tasks, deliverables, specifications, and performance standards. A critical strategic element is the explicit listing of exclusions ▴ what is not included in the contractor’s responsibilities.

This preempts future claims for extra compensation for work the owner assumed was included. The SOW must also clearly define the owner’s own responsibilities, such as providing site access or timely decisions, as failure to do so can lead to delay claims from the contractor.

Second, clauses governing Time must establish a clear framework for the project schedule, including milestone dates and the final completion date. A “no-damages-for-delay” clause is a powerful tool for owners, stipulating that if the owner causes a delay, the contractor’s sole remedy is a time extension, not monetary compensation. However, for this to be effective and fair, it must be paired with a clear and efficient process for granting such extensions. The strategy also involves defining what constitutes a compensable versus a non-compensable delay, distinguishing between owner-caused issues and external events covered by a Force Majeure clause.

Third, Payment clauses must be structured to reinforce project control. Progress payments should be explicitly tied to the achievement of verifiable milestones outlined in the SOW. The clause should also define the terms of retention ▴ a percentage of payment withheld until final project acceptance ▴ as a powerful incentive for the contractor to complete all punch-list items and deliver a fully functional project.

A Comparative Analysis of Liability Frameworks

The choice of project delivery method profoundly impacts the owner’s liability profile and dictates the strategic emphasis of the RFP clauses. Different models allocate design and construction responsibility in distinct ways, requiring a tailored approach to risk mitigation.

The table below compares three common project delivery models and their implications for the owner’s liability, highlighting which RFP clauses become most critical in each context.

| Project Delivery Model | Primary Locus of Risk | Owner’s Inherent Liability | Most Critical RFP Clauses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design-Bid-Build (DBB) | Separation of Design and Construction | Owner holds separate contracts with the designer and builder, making the owner responsible for any errors or omissions in the design documents provided to the builder. | – Scope of Work (to ensure builder follows design precisely) – Differing Site Conditions – Errors and Omissions Insurance (for the designer) |

| Design-Build (DB) | Single Point of Responsibility | Owner’s liability is significantly reduced as the design-build entity is responsible for both design and construction, including the coordination between them. | – Performance Specifications (defining the desired outcome) – Professional Liability Insurance (for the DB entity) – Acceptance Criteria and Testing Protocols |

| Construction Manager at Risk (CMAR) | Collaboration and Cost Control | Owner is liable for the design (contracted separately) but the CMAR provides pre-construction input and accepts financial risk for construction cost and schedule via a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP). | – Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) Provisions – Definition of Reimbursable vs. Non-Reimbursable Costs – Change Order Management |

Execution

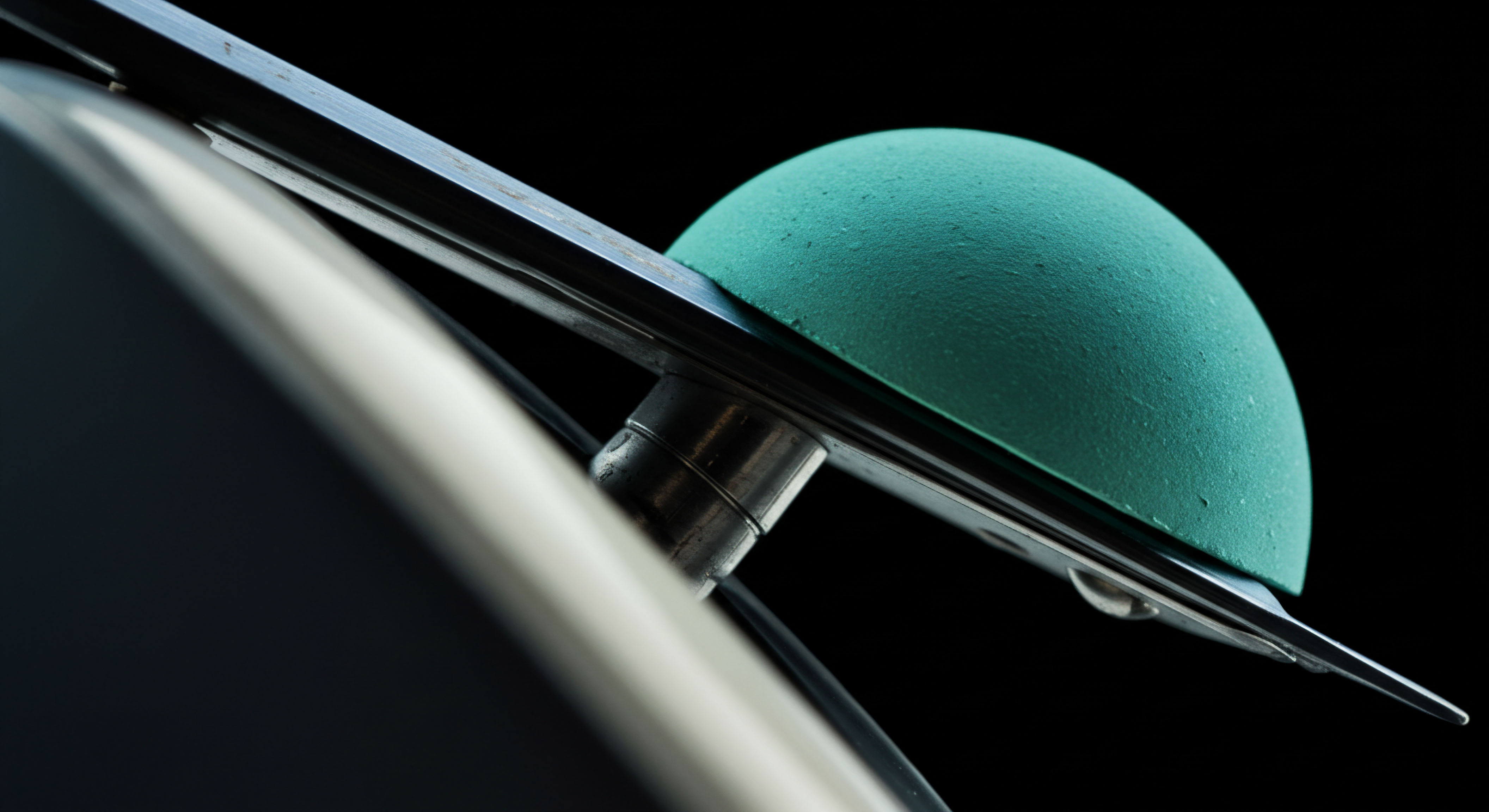

The Indemnification Protocol

The indemnification clause is the primary engine for transferring third-party liability from the owner to the contractor. Its execution in an RFP must be precise and legally sound to be enforceable. The core of the clause is the “defend, indemnify, and hold harmless” covenant. “Indemnify” refers to the duty to reimburse for losses, while “defend” creates a separate, and equally important, obligation for the contractor to pay for the legal defense against a claim from the moment it is asserted.

“Hold harmless” reinforces this protective shield. The execution of this clause involves defining its trigger and its scope with meticulous care.

The trigger is typically tied to claims “arising from” or “related to” the contractor’s negligent acts or omissions. The scope must clearly state that this obligation applies to claims involving bodily injury, death, and property damage. A critical execution detail is to ensure the clause explicitly survives the termination of the contract, as claims may arise long after the project is complete. It is also vital to address the issue of comparative fault.

Most jurisdictions will not enforce a clause that indemnifies an owner for their own sole negligence. Therefore, the clause should be written to apply “to the extent” the contractor or its subcontractors are at fault, ensuring proportionality and legal durability.

- Triggering Language ▴ The clause should be activated by claims, demands, losses, or liabilities “arising out of or resulting from the performance of the Contractor’s Work.”

- Covered Parties ▴ The clause must protect the “Owner, its officers, agents, and employees” from liability.

- Exclusions ▴ It is common to specifically exclude claims arising from the sole negligence or willful misconduct of the owner or defects in the design provided by the owner’s separate consultants.

- Defense Obligation ▴ The clause must explicitly state that the duty to defend is immediate upon a tender of the claim by the owner, independent of the final determination of liability.

The Insurance Mandate

Insurance clauses do not replace indemnification; they provide the financial backing to ensure the indemnification promise can be fulfilled. Executing this section of the RFP requires specifying not just the types of insurance but also the required limits, endorsements, and verification procedures. Simply stating “contractor shall carry insurance” is a significant failure of execution. The RFP must function as a detailed insurance specification sheet.

The owner must be named as an “Additional Insured” on the contractor’s Commercial General Liability (CGL) policy. This provides the owner with direct rights under the policy. Furthermore, the RFP must demand a “Waiver of Subrogation” on all required policies.

This prevents the contractor’s insurance company from suing the owner to recover funds it paid out for a claim, even if the owner was partially at fault. The execution of this mandate is not complete without a requirement for the contractor to provide certificates of insurance as proof of coverage before commencing work.

A contractor’s insurance policy is the financial engine that powers their indemnification obligations; without it, an indemnity clause is merely an unfunded promise.

The following table outlines a baseline for insurance requirements in a major project RFP. The limits should be adjusted based on project size, risk, and location.

| Type of Insurance | Minimum Limit per Occurrence | Minimum Aggregate Limit | Critical Endorsements & Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial General Liability (CGL) | $2,000,000 | $4,000,000 | – Owner named as Additional Insured (ISO Form CG 20 10 or equivalent) – Waiver of Subrogation in favor of the Owner – Primary and Non-Contributory wording |

| Automobile Liability | $1,000,000 | N/A | – Coverage for all owned, non-owned, and hired vehicles – Waiver of Subrogation in favor of the Owner |

| Workers’ Compensation & Employer’s Liability | Statutory Limits | $1,000,000 | – Waiver of Subrogation in favor of the Owner |

| Professional Liability (E&O) (if contractor has design responsibility) | $5,000,000 | $5,000,000 | – Coverage for design errors and omissions – Retroactive date prior to start of work |

| Umbrella / Excess Liability | $10,000,000 | $10,000,000 | – Follow-form coverage over underlying CGL, Auto, and Employer’s Liability policies |

Defining the Boundaries of Work

The Scope of Work (SOW) clause is the most fertile ground for disputes. Its proper execution is the single most effective way to prevent claims related to change orders and extra work. The SOW must be a comprehensive, standalone document that leaves no room for interpretation. It must detail not only what the contractor must do but also the standards to which they must perform.

A well-executed SOW includes the following components:

- A Detailed Description of the Work ▴ This section breaks down the project into discrete tasks and phases. It should reference all relevant drawings, specifications, and technical documents, incorporating them by reference into the RFP.

- A List of Deliverables ▴ This enumerates all tangible and intangible items the contractor is required to produce, from physical construction to reports, as-built drawings, and warranties.

- Performance and Quality Standards ▴ This specifies the required quality of materials and workmanship, referencing industry standards (e.g. ASTM, ANSI, ISO) where applicable. It also defines the criteria for acceptance of the work.

- A Clear Statement of Exclusions ▴ To prevent disputes, this section explicitly lists items that are not the contractor’s responsibility. This could include things like hazardous material abatement (if handled by a separate contractor), utility connection fees, or specific site preparations being handled by the owner.

- Owner’s Responsibilities ▴ This defines the owner’s obligations, such as providing timely access to the site, furnishing necessary information or equipment, and the turnaround time for reviewing submittals. This protects the owner from delay claims based on their own lack of performance.

The Dispute Resolution Cascade

Even with the most meticulously drafted RFP, disputes can arise. The strategic execution of a dispute resolution clause is about creating a structured, multi-tiered process that encourages resolution at the lowest possible level, avoiding costly and time-consuming litigation. The goal is to create a “cascade” that filters disputes through progressively more formal mechanisms.

The first tier should be mandatory, informal negotiation between the project managers of the owner and contractor. This resolves the majority of issues quickly. If that fails, the next step is formal mediation, where a neutral third-party facilitator helps the parties reach a mutually agreeable settlement. The key is that mediation is non-binding.

The final tier, only to be used if mediation fails, is binding arbitration or litigation. The RFP must specify which of these final methods will be used, including the rules that will govern the process (e.g. American Arbitration Association rules), the location (venue), and the governing law. This structured cascade provides predictability and control over the dispute process, preventing a minor disagreement from immediately escalating into a major lawsuit.

References

- Hinze, Jimmie. Construction Contracts. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Education, 2011.

- Fisk, Edward R. and Wayne D. Reynolds. Construction Project Administration. 10th ed. Pearson, 2013.

- American Institute of Architects. AIA Document A201-2017, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction. The American Institute of Architects, 2017.

- Callahan, Michael T. Construction Change Order Claims. 2nd ed. Aspen Publishers, 2005.

- Schneier, Adam. “The Use of Limitation of Liability Clauses in Construction Contracts.” Journal of the American College of Construction Lawyers, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1-25.

- Heuer, Charles R. The Law of Construction Disputes. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Lam, Patrick T.I. et al. “A Comparative Study of Risk Allocation in Construction Contracts in Asia.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 133, no. 1, 2007, pp. 93-104.

- Thomas, H. Randolph. Construction Contract Staffing. Transportation Research Board, 2006.

Reflection

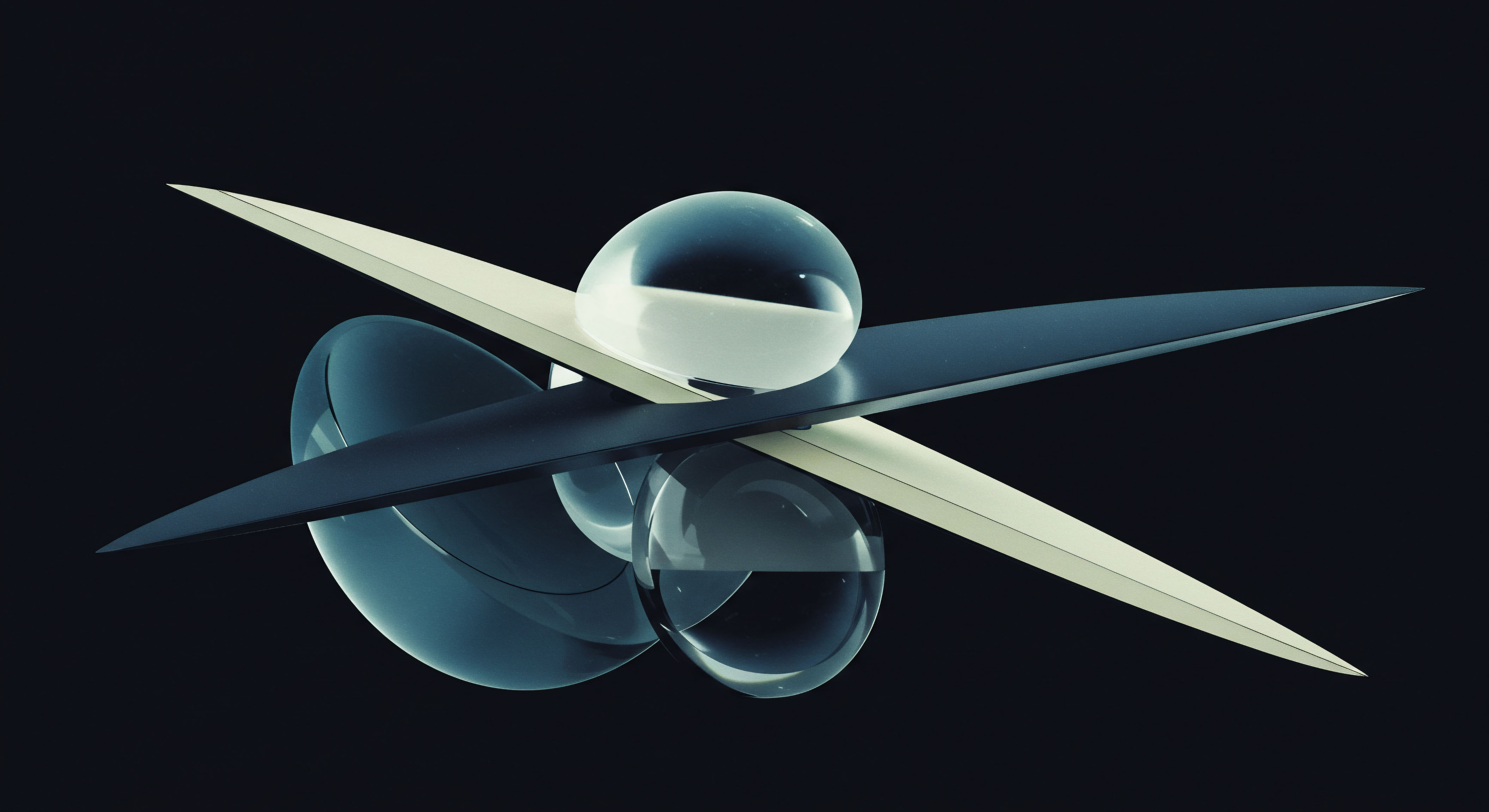

The RFP as a System of Controls

The assembly of these clauses transforms the Request for Proposal from a static document into a dynamic system for governing risk. It is a framework engineered not for a perfect project, but for an imperfect one ▴ the only kind that truly exists. The clauses are control surfaces, allowing the owner to navigate the turbulence of construction, from unforeseen site conditions to third-party actions. Each provision is an input that calibrates the relationship with the contractor, defining the operational physics of the project before it ever breaks ground.

The ultimate objective extends beyond the mere legal defensibility of individual clauses. It is about creating a coherent, integrated system where the insurance mandate funds the indemnity protocol, and the dispute resolution cascade provides a safe failure mode. The precision of the scope of work provides the data upon which the change order process operates. Viewing the RFP through this systemic lens elevates the task from legal drafting to strategic design.

It is the construction of a governance framework. Ultimately, risk is never eliminated.

Glossary

Risk Allocation

Indemnification Clause

Limitation of Liability

Scope of Work

Force Majeure

Waiver of Subrogation

Additional Insured