Concept

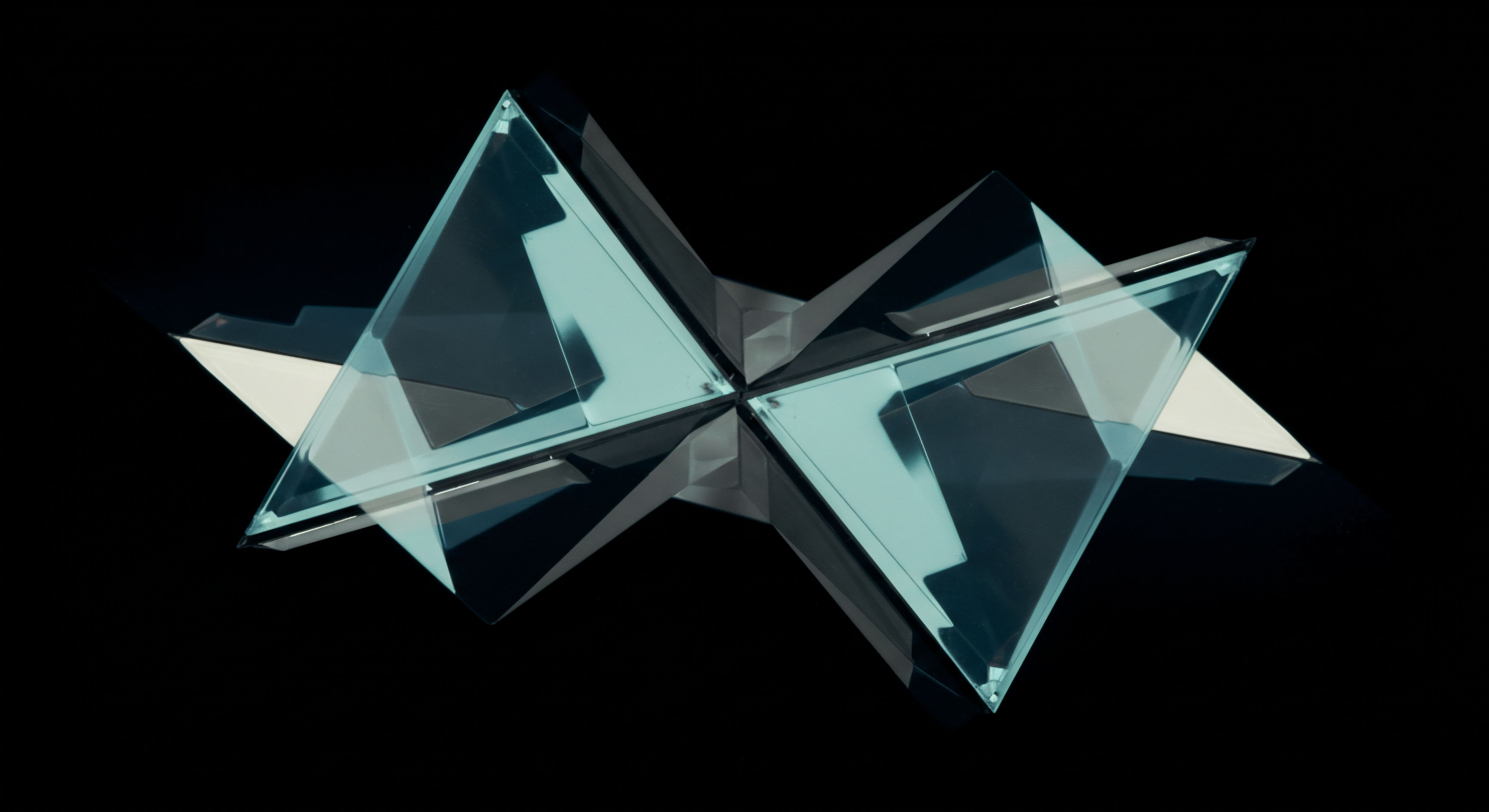

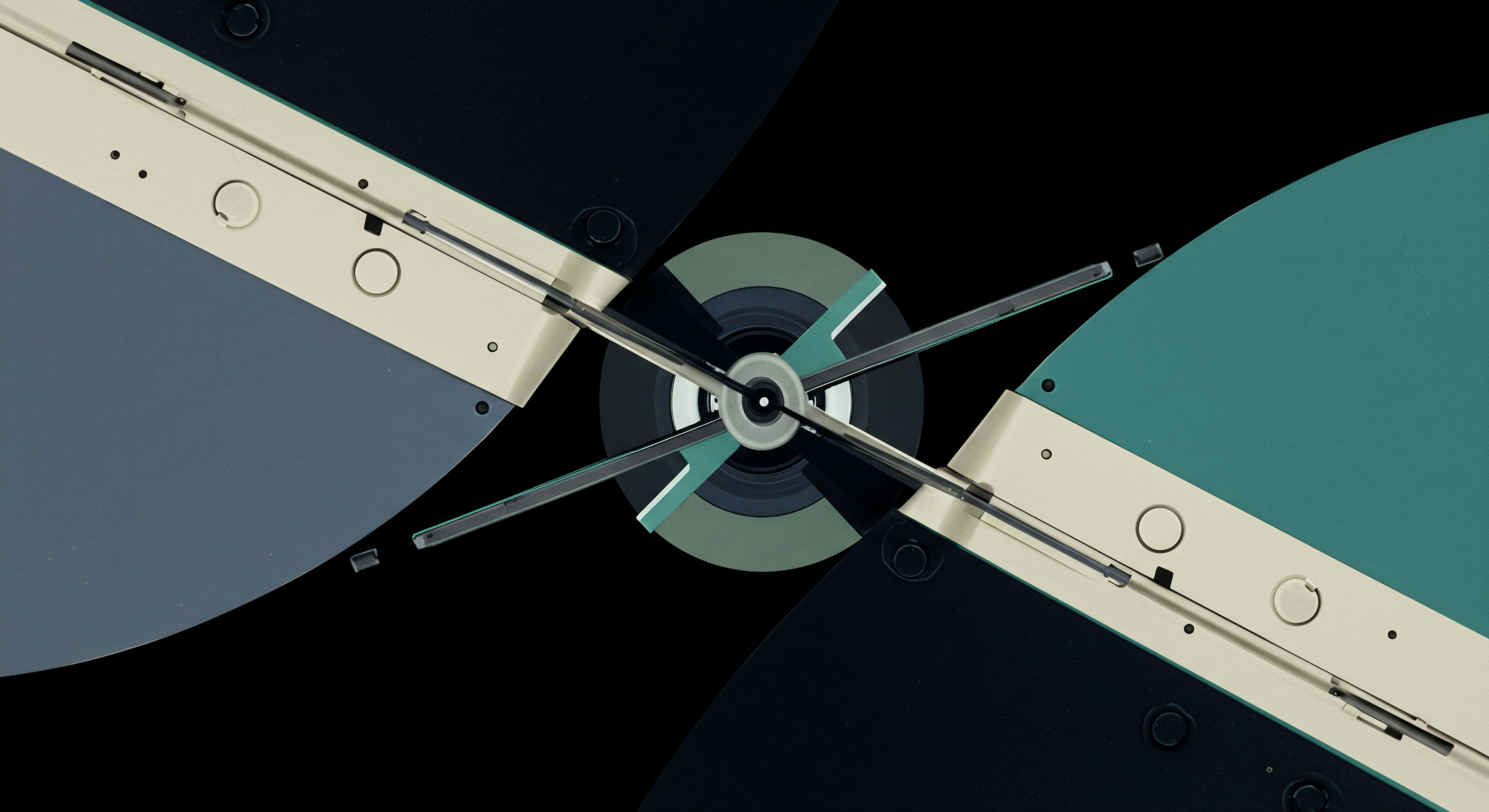

The core architecture of modern financial markets rests upon a foundational principle ▴ the mitigation of counterparty credit risk. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the global regulatory mandate shifted decisively toward central clearing for standardized derivatives. This architectural redesign was intended to dismantle the complex, opaque web of bilateral exposures that proved so fragile. The solution was the elevation of the Central Counterparty (CCP), an entity designed to act as a systemic shock absorber.

By stepping between every buyer and seller, the CCP transforms a chaotic mesh of point-to-point connections into an orderly hub-and-spoke model. It nets exposures, demands collateral in the form of margin, and establishes a clear, rules-based process for managing the default of a participant. This structure is, in theory, a profound upgrade to the stability of the financial operating system.

This very solution, however, introduces a new and formidable vector of systemic risk. The system’s resilience is now predicated on the resilience of these central nodes. Risk that was once distributed, albeit opaquely, across hundreds of institutions is now highly concentrated within a few systemically critical CCPs. These entities are no longer just market utilities; they are behemoths of risk management, the failure of which would trigger a cascade of catastrophic consequences across the global financial system.

The concentration of risk within a CCP creates a single point of failure whose scale is unprecedented. The failure of a major CCP would not be a localized event; it would be a systemic cataclysm, freezing critical markets and propagating losses through a network of clearing members who are, by definition, the largest and most interconnected financial institutions.

The fundamental paradox of central clearing is that in solving the problem of bilateral counterparty risk, it creates a new, highly concentrated, and potentially more dangerous form of systemic vulnerability.

Understanding the potential systemic risks associated with this concentration requires viewing the CCP as more than a simple intermediary. It is the central processing unit of its market. It dictates the terms of engagement, manages immense flows of capital and collateral, and holds the ultimate responsibility for market integrity. The risks, therefore, are not merely financial; they are operational, legal, and structural.

They include the immense liquidity demands a CCP can place on its members during times of stress, the procyclical nature of its margin calls which can exacerbate a crisis, and the moral hazard that arises when an entity becomes so critical that it is implicitly guaranteed by the state. The default of a single, large clearing member can stress a CCP to its limits, but the failure of the CCP itself is an event horizon from which the market may not easily return.

Strategy

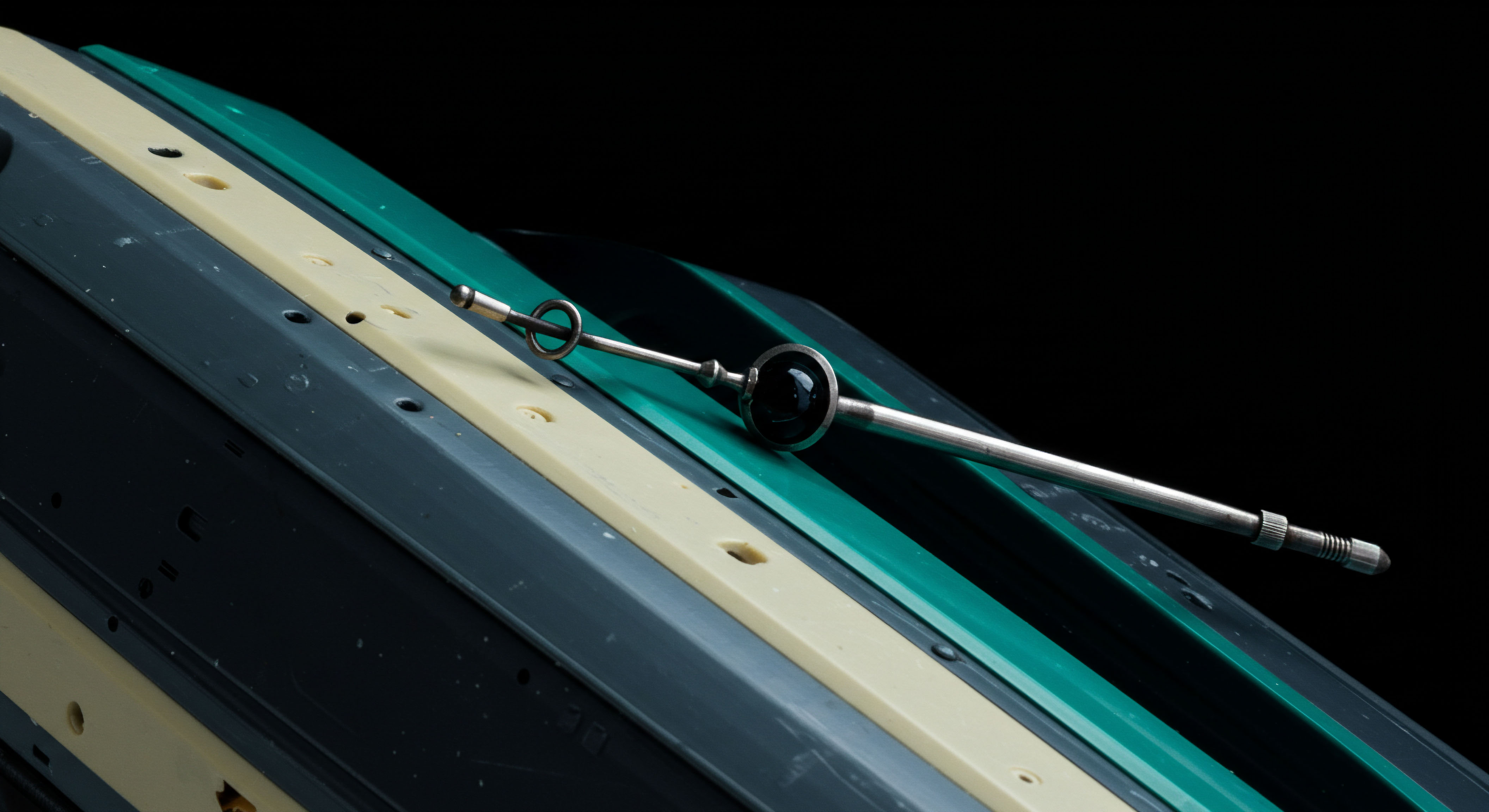

The strategic framework for managing the immense concentration of risk within a Central Counterparty is built upon a multi-layered defense system. This system is designed to absorb the impact of a clearing member default in a sequential and predictable manner. The primary architecture for this defense is the CCP’s “default waterfall,” a tiered structure of financial resources that are called upon to cover losses.

The design and calibration of this waterfall represent the core strategic trade-off for a CCP ▴ ensuring extreme resilience while maintaining a cost structure that encourages, rather than discourages, central clearing. Each layer of the waterfall has distinct strategic implications for the CCP, its clearing members, and the financial system at large.

The Default Waterfall Architecture

The default waterfall is a predefined sequence for the allocation of losses following a member default. It is the operational manifestation of the principle of mutualized risk. The process is designed to be rapid and unambiguous, providing certainty to the market during a period of extreme stress. The typical structure proceeds as follows:

- Defaulting Member’s Resources ▴ The first line of defense is always the capital and collateral posted by the defaulting member. This includes their initial margin and their contribution to the default fund. This layer ensures that the primary party responsible for the losses bears the initial impact, aligning incentives for prudent risk management at the member level.

- CCP’s “Skin-in-the-Game” (SITG) ▴ The second layer is a dedicated portion of the CCP’s own capital. This contribution, though typically smaller than the other layers, is strategically vital. It demonstrates that the CCP has a direct financial stake in the effectiveness of its own risk management models and default management processes, mitigating moral hazard on the part of the CCP itself.

- Non-Defaulting Members’ Default Fund Contributions ▴ The third and largest layer of pre-funded resources is the mutualized default fund, contributed by all non-defaulting clearing members. This is the core of the mutualized risk model. The surviving members absorb the remainder of the losses, up to the total amount of the fund. This creates a powerful incentive for members to monitor the riskiness of their peers and to actively participate in the CCP’s default management process, such as in the auction of a defaulter’s portfolio.

Beyond the Waterfall Recovery Tools

In the event of an extreme market shock that exhausts all pre-funded resources in the waterfall, the CCP must resort to recovery tools. These are mechanisms designed to allocate further losses and recapitalize the CCP to ensure its continued operation. The choice of recovery tool has profound strategic consequences.

The two primary recovery tools are:

- Assessments (Cash Calls) ▴ The CCP has the right to levy additional cash calls on its surviving clearing members to cover any remaining losses. These calls are typically capped at a multiple of the member’s default fund contribution. This tool is predictable and transparent, as the maximum potential liability is known in advance. However, it can create immense liquidity pressure on surviving members precisely when liquidity is most scarce in the broader market, potentially triggering further defaults.

- Variation Margin Gains Haircutting (VMGH) ▴ This tool involves the CCP reducing the variation margin payments owed to members with profitable positions. In effect, the gains of “winning” traders are used to cover the losses of the defaulter. While this avoids calling for new cash from members, its impact is arbitrary and unpredictable. A member’s liability is determined by their market position at a specific moment in time, not by their overall risk contribution to the CCP. This can undermine confidence in the clearing system, as profitable positions are no longer guaranteed.

A CCP’s resilience is a direct function of its default waterfall and recovery tools, which must be calibrated to handle extreme events without creating destabilizing contagion effects.

How Do Recovery Tools Compare Strategically?

The strategic choice between assessments and VMGH involves a difficult trade-off between liquidity risk and incentive alignment. The following table provides a comparative analysis of these two critical recovery tools.

| Strategic Parameter | Assessments (Cash Calls) | Variation Margin Gains Haircutting (VMGH) |

|---|---|---|

| Predictability | High. Member liability is typically capped and known in advance based on their default fund contribution. | Low. Liability depends on the member’s intraday trading position at the moment of crisis, which is unpredictable. |

| Incentive Alignment | Strong. Liability is linked to a member’s risk-based contribution, preserving the “polluter pays” principle. | Weak. It penalizes members with profitable trades, regardless of their risk profile, potentially discouraging market-making. |

| Liquidity Impact | Severe. Can trigger a systemic liquidity drain as all members are forced to find cash during a crisis. | Muted. Does not require members to source new funds; it reduces their incoming cash flows. |

| Systemic Contagion Risk | High potential for liquidity-driven contagion, where cash calls on healthy firms cause them to fail. | High potential for confidence-driven contagion, as it undermines the fundamental premise of guaranteed settlement of gains. |

| Fairness Perception | Perceived as fair, as the cost is socialized based on a pre-agreed, risk-based formula. | Perceived as arbitrary and unfair, as it penalizes profitable, prudent trading. |

Execution

Executing a robust strategy to navigate the concentrated risks of central clearing requires a deep, operational understanding of the underlying mechanics. For an institutional market participant, this extends far beyond a theoretical appreciation of the default waterfall. It demands a granular, quantitative approach to risk modeling, a clear-eyed analysis of potential failure scenarios, and a technical architecture capable of supporting real-time risk management and system integration. This is where the abstract concept of systemic risk is translated into concrete operational protocols and quantitative measures.

The Operational Playbook

For a clearing member, managing exposure to a CCP is an active, ongoing process. It requires a comprehensive operational playbook that integrates due diligence, risk monitoring, and crisis preparedness. The following playbook outlines the essential steps a member firm must execute to manage its contingent liabilities and ensure its own resilience in the face of a potential CCP crisis.

-

Comprehensive Rulebook Analysis

The CCP’s rulebook is the legally binding document that governs all aspects of the clearing relationship. A member firm must conduct a thorough legal and operational analysis of this document, focusing on the sections pertaining to default management.

- Default Waterfall Mechanics ▴ Confirm the exact sequence and composition of the default waterfall. Identify the size of the CCP’s “skin-in-the-game” and the total size of the mutualized default fund.

- Recovery Tool Provisions ▴ Scrutinize the language governing recovery tools. What are the precise triggers for their use? For cash calls, what is the maximum assessment power (e.g. 1x, 2x, or 3x the default fund contribution)? For VMGH, what is the exact methodology for calculating haircuts?

- Portfolio Auction Process ▴ Understand the procedures for the auction of a defaulted member’s portfolio. Who is eligible to bid? What are the timelines? A failed auction is a key trigger for the escalation of a crisis.

- Active Participation in CCP Governance Clearing members are not passive users; they are stakeholders in the CCP. Active participation in risk committees and working groups provides invaluable insight into the CCP’s risk management philosophy and allows the member to influence policies that directly affect its own safety.

-

Internal Liquidity Stress Testing

A member firm must model the potential liquidity impact of a CCP crisis. This involves running internal stress tests that simulate the simultaneous demand for cash from multiple sources.

- Scenario 1 Maximum Assessment ▴ Model the full cash outflow required if the CCP exercises its maximum assessment power. Ensure that sufficient high-quality liquid assets are available to meet this call without resorting to fire sales of other assets.

- Scenario 2 Variation Margin Shock ▴ Model the impact of a sudden, extreme market move on variation margin requirements. This is a separate but related liquidity strain that will likely occur concurrently with a member default.

- Default Management Drills Participate actively in all CCP-led default management drills. These exercises test a firm’s operational readiness to respond to a crisis. This includes testing communication protocols, the ability to value and bid on a complex portfolio under pressure, and the speed of mobilizing liquidity.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

To move beyond qualitative assessment, firms must quantitatively model their exposure to a CCP default. The cornerstone of this analysis is a stress test that simulates the depletion of the default waterfall under an extreme but plausible scenario. The standard regulatory requirement is for a CCP to be able to withstand the default of its two largest members (a “Cover 2” event) under such conditions.

The following table models a hypothetical Cover 2 stress test for a CCP. This analysis allows a member to understand its own position within the waterfall and the potential losses it would incur.

Hypothetical Cover 2 Default Waterfall Stress Test

| Entity / Waterfall Layer | Prefunded Resources (USD Millions) | Stress Loss from Member 1 (USD Millions) | Stress Loss from Member 2 (USD Millions) | Remaining Resources after Loss Allocation (USD Millions) | Loss Incurred by Layer (USD Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defaulter 1 Resources (IM & DF) | 800 | 1,500 | – | 0 | 800 |

| Defaulter 2 Resources (IM & DF) | 650 | – | 1,200 | 0 | 650 |

| CCP Skin-in-the-Game (SITG) | 250 | – | – | 0 | 250 |

| Non-Defaulting Member A (DF Cont.) | 150 | – | – | 0 | 150 |

| Non-Defaulting Member B (DF Cont.) | 120 | – | – | 0 | 120 |

| Non-Defaulting Member C (DF Cont.) | 100 | – | – | 0 | 100 |

| Other Non-Defaulting Members (DF Cont.) | 730 | – | – | 200 | 530 |

| Total Prefunded Resources | 2,800 | 1,500 | 1,200 | 200 | 2,600 |

Analysis of the Model

In this hypothetical scenario, the simultaneous default of the two largest members creates a total stress loss of $2.7 billion ($1.5B + $1.2B). The model shows the waterfall operating as designed:

- The resources of the two defaulting members ($800M + $650M = $1.45B) are consumed first.

- The CCP’s own capital ($250M) is then used, bringing the total absorbed loss to $1.7B.

- The remaining loss of $1.0B is covered by the default fund contributions of the non-defaulting members. The entire contributions of Members A, B, and C are consumed, along with $530M from the rest of the members.

- The CCP remains solvent with $200M of its default fund intact. No recovery tools are needed.

A clearing member would use such a model, populated with real data from the CCP, to calculate its own “loss-given-default-of-the-waterfall” and to assess the adequacy of the CCP’s total resources.

Predictive Scenario Analysis

Quantitative models provide a sterile view of a crisis. To truly understand the systemic implications, one must walk through a narrative scenario. This analysis combines the mechanics of the waterfall with the human and market dynamics of a crisis.

Case Study The Sovereign Shock Event

At 08:00 GMT, the government of a G7 nation unexpectedly announces an immediate restructuring of its sovereign debt, citing a fiscal crisis. The news triggers unprecedented volatility in global interest rate swap markets. “FuturaClear,” a systemically important CCP that clears the majority of these swaps, is at the epicenter of the crisis.

One of its largest clearing members, “Titan Capital,” has a massive, unhedged exposure to the nation’s long-term interest rates. As rates skyrocket, Titan’s portfolio hemorrhages value. At 10:00 GMT, FuturaClear issues an intraday margin call to Titan for $5 billion.

Titan, facing its own liquidity crisis as credit lines are pulled, fails to meet the call. At 11:00 GMT, FuturaClear formally declares Titan in default.

The Default Management Group is activated. The first step is to hedge the risk of Titan’s portfolio. The extreme volatility makes this nearly impossible. Hedging attempts are only partially successful and come at a huge cost.

The next step is to auction the portfolio. FuturaClear breaks the massive portfolio into smaller, more digestible chunks and invites bids from its surviving members.

The auction begins at 14:00 GMT. The first tranche receives no bids. The market is too volatile, the portfolio’s risks too opaque. The surviving members are nursing their own losses and are unwilling to take on the massive, toxic positions of their fallen competitor.

The second and third tranches also fail. The failed auction is a catastrophic signal to the market. It demonstrates that the risk cannot be transferred. It must be absorbed by the waterfall.

FuturaClear begins the loss allocation process. Titan’s initial margin and default fund contribution of $8 billion are wiped out. The CCP’s own “skin-in-the-game” of $1 billion is consumed next.

The total loss, however, is calculated to be $25 billion. This leaves a $16 billion hole to be filled by the non-defaulting members’ default fund, which totals only $15 billion.

At 16:00 GMT, the entire pre-funded default fund is exhausted. The crisis has breached the walls of the fortress. FuturaClear is still short $1 billion. The CEO, in consultation with regulators, makes a fateful decision.

They will not use VMGH, fearing a complete collapse of confidence. Instead, they will exercise their right to a cash call. They issue a pro-rata assessment to all surviving clearing members to cover the $1 billion shortfall and to begin the process of recapitalizing the default fund. For a large member, this amounts to an immediate, unplanned demand for over $100 million in cash. This demand ripples through the system, forcing healthy firms to sell assets into a falling market to raise the necessary funds, amplifying the initial shock and threatening to trigger the next wave of defaults.

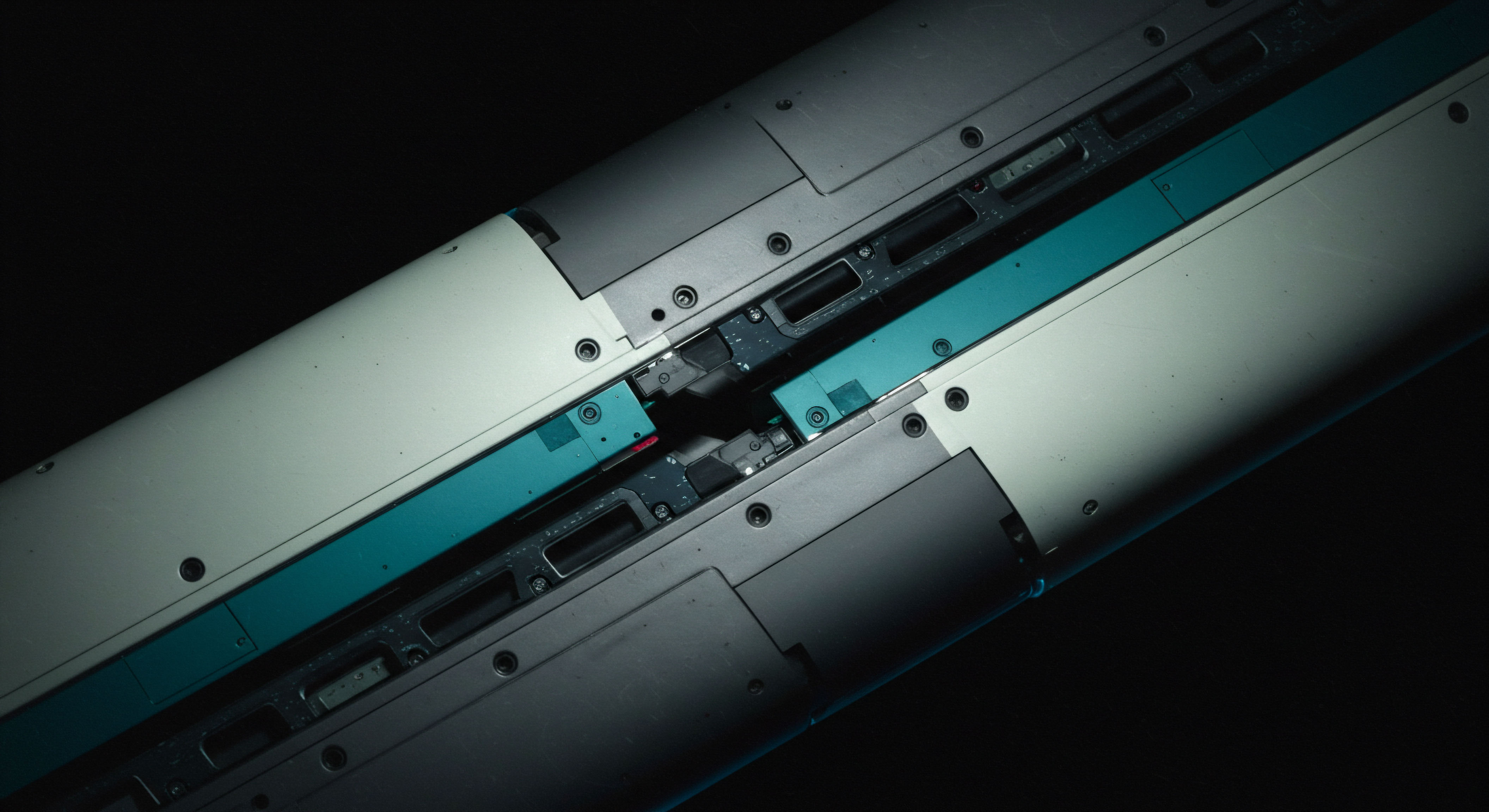

System Integration and Technological Architecture

The effective management of CCP risk is underpinned by a sophisticated and robust technological architecture. The data flows and system integrations between a clearing member and a CCP are constant and complex, requiring significant investment in technology and infrastructure.

The core components of this architecture include:

- Trade Capture and Novation ▴ Member firms’ trading systems must be integrated with the CCP via low-latency messaging protocols, typically variants of the Financial Information eXchange (FIX) protocol. As trades are executed, they are sent to the CCP for validation and novation, the legal process by which the CCP becomes the counterparty to both sides of the trade.

- Real-Time Risk and Margin APIs ▴ CCPs provide APIs that allow members to calculate their initial and variation margin requirements in real-time. A member’s internal risk systems must continuously pull this data to manage their own liquidity and credit exposures to their clients. This is critical for preventing a client default from cascading into a member default.

- Collateral Management Systems ▴ These systems track the eligibility, valuation, and location of all collateral posted to the CCP. They must be able to manage the operational complexity of substituting collateral and meeting margin calls in multiple currencies and asset types.

- Default Management Platforms ▴ In a crisis, the CCP will activate a specific technology platform for managing the default. This platform is used to disseminate information about the defaulted portfolio, manage the auction process, and communicate with surviving members. Member firms must have the technical capability to connect to and operate on this platform under extreme pressure.

References

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures & International Organization of Securities Commissions. “Recovery of financial market infrastructures.” Bank for International Settlements, 2014.

- Duffie, Darrell. “Resolution of Failing Central Counterparties.” In Making Failure Feasible ▴ How Bail-in, Resolution and Cross-Border Cooperation Can End Too Big to Fail, edited by Viral V. Acharya, Thorsten Beck, and Douglas D. Evanoff, 215-236. World Scientific, 2016.

- Cont, Rama. “The End of the Waterfall ▴ A Survival-Based Framework for CCP Default and Recovery.” Journal of Financial Market Infrastructures, vol. 4, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-28.

- Financial Stability Board. “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions.” 2014.

- Menkveld, Albert J. and Guillaume Vuillemey. “The Economics of Central Clearing.” Annual Review of Financial Economics, vol. 12, 2020, pp. 279-301.

- Nosal, Jaromir, and Robert Steigerwald. “What Is a Central Counterparty?” Chicago Fed Letter, no. 301, 2012.

- Pirrong, Craig. “The Economics of Central Clearing ▴ Theory and Practice.” ISDA Discussion Papers Series, no. 1, 2011.

- Heath, A. Kelly, G. & Manning, M. (2013). “Central Counterparties ▴ What are They, and What is Their Role in Financial Stability?”. Reserve Bank of Australia.

Reflection

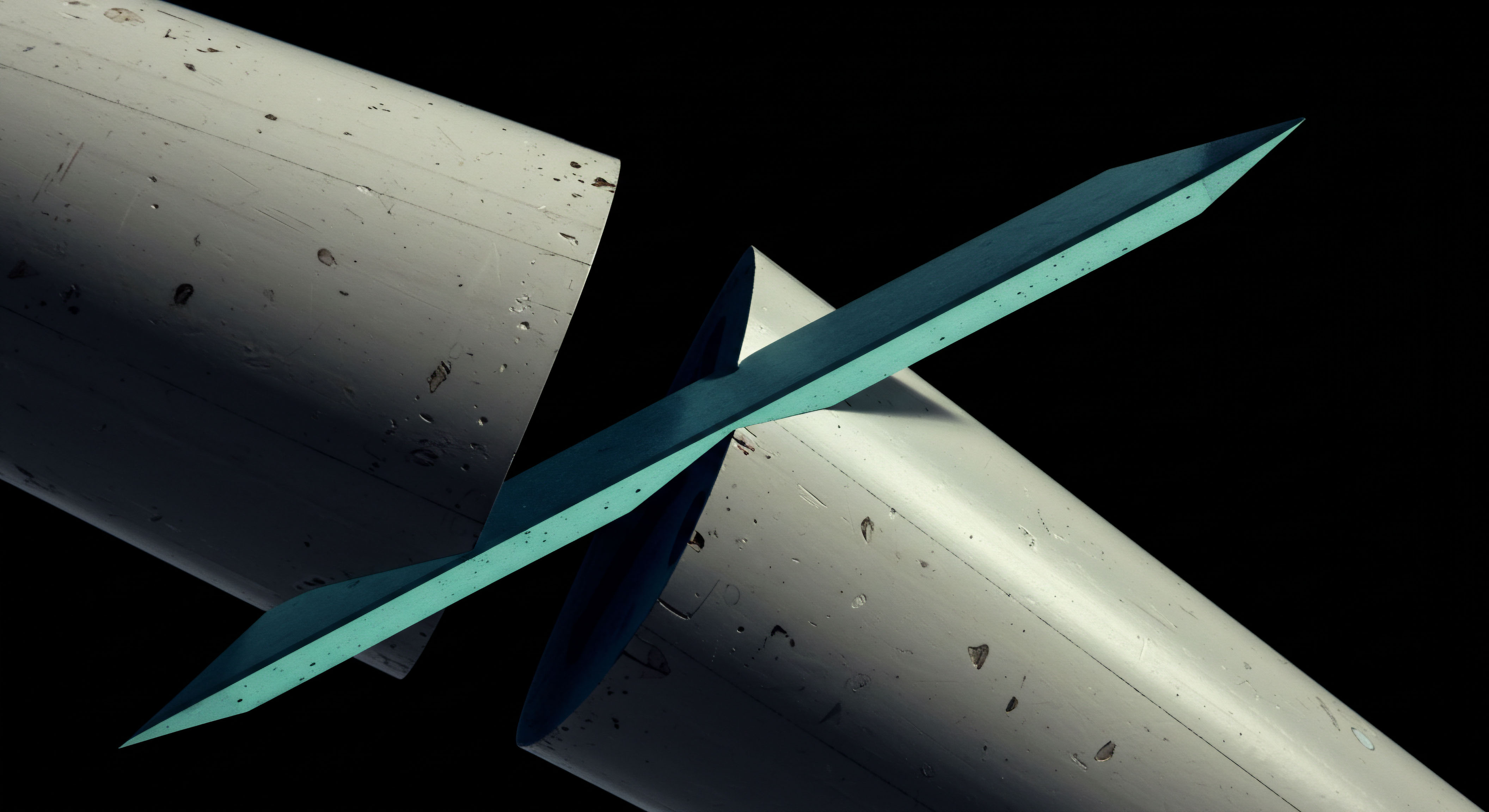

The architectural shift toward central clearing has fundamentally reconfigured the topology of systemic risk. The knowledge of the default waterfall, the quantitative models, and the operational playbooks provides a necessary framework for navigating this new landscape. Yet, true resilience extends beyond the mastery of these mechanics. It requires a deeper introspection into your own organization’s operational framework and its capacity to withstand a systemic shock that originates from a node previously considered a source of safety.

How does your firm’s internal liquidity framework account for the simultaneous stress of extreme margin calls and a maximum assessment cash call? Is your technological architecture robust enough to participate effectively in a distressed portfolio auction under chaotic market conditions? The answers to these questions define the boundary between surviving a crisis and becoming a vector for its transmission.

The concentration of risk in central counterparties has created a system where the resilience of each participant is inextricably linked to the resilience of the whole. A superior operational framework is the ultimate determinant of a firm’s ability to remain standing when the waterfall breaks.

Glossary

Counterparty Credit Risk

Central Counterparty

Risk Management

Systemic Risk

Clearing Members

Clearing Member

Default Waterfall

Member Default

Central Clearing

Default Fund

Default Management

Skin-In-The-Game

Default Fund Contributions

Mutualized Default Fund

Recovery Tools

Default Fund Contribution

Surviving Members

Variation Margin Gains Haircutting

Variation Margin

Liquidity Risk

Cash Calls

Cover 2 Stress Test