Concept

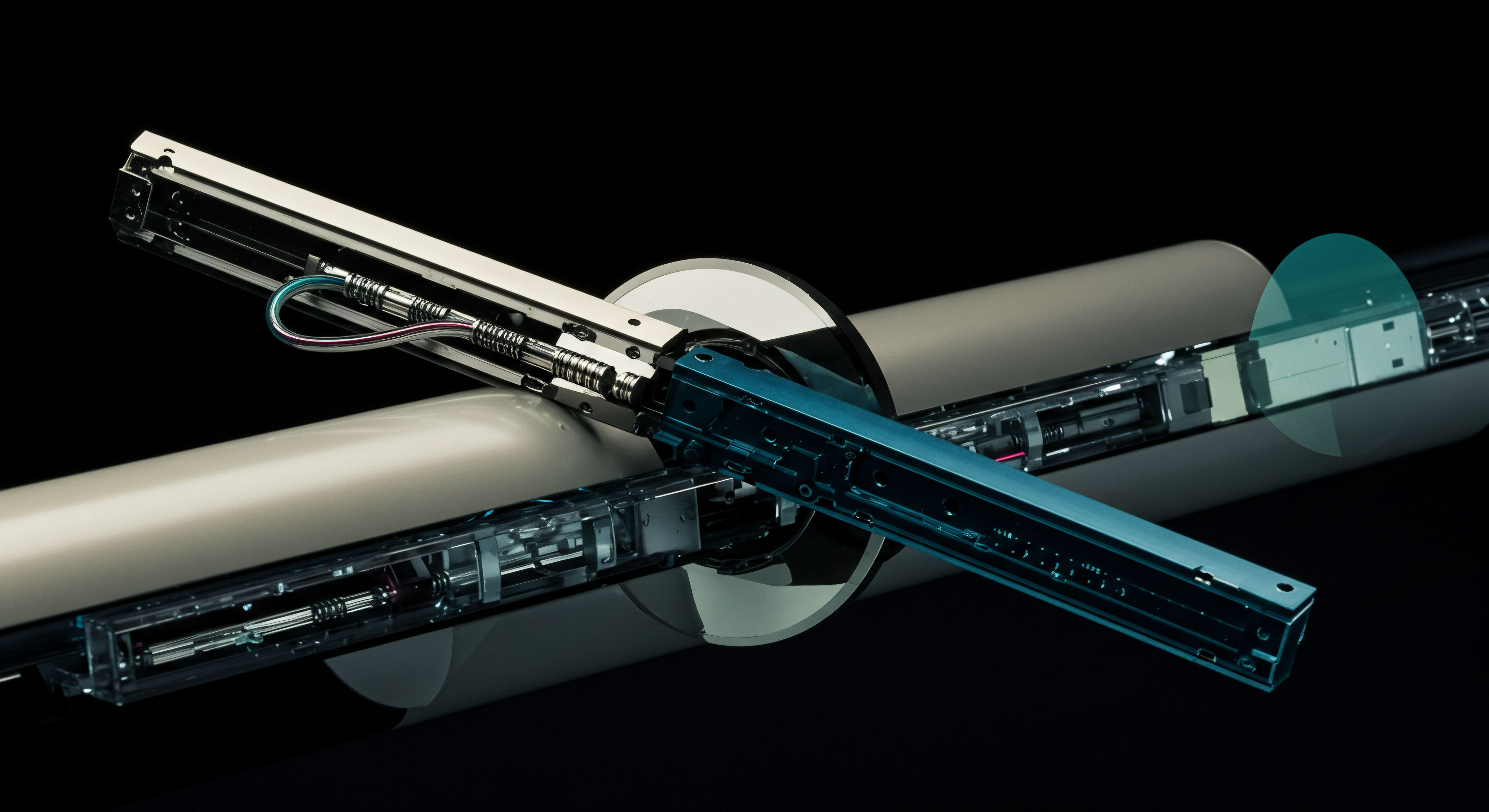

The analysis of counterparty risk in modern financial markets requires a precise understanding of the underlying architecture of the entities providing liquidity. When a trading principal selects a counterparty, they are not merely choosing a price; they are interfacing with a complex system, each with its own operational logic, capital structure, and risk profile. The distinction between a bank dealer and an electronic market maker (EMM) represents a fundamental divergence in these systems.

Your decision to face one over the other is a strategic choice with profound implications for risk exposure and execution quality. The core of this distinction lies in the source and nature of their balance sheets and the regulatory frameworks that govern them.

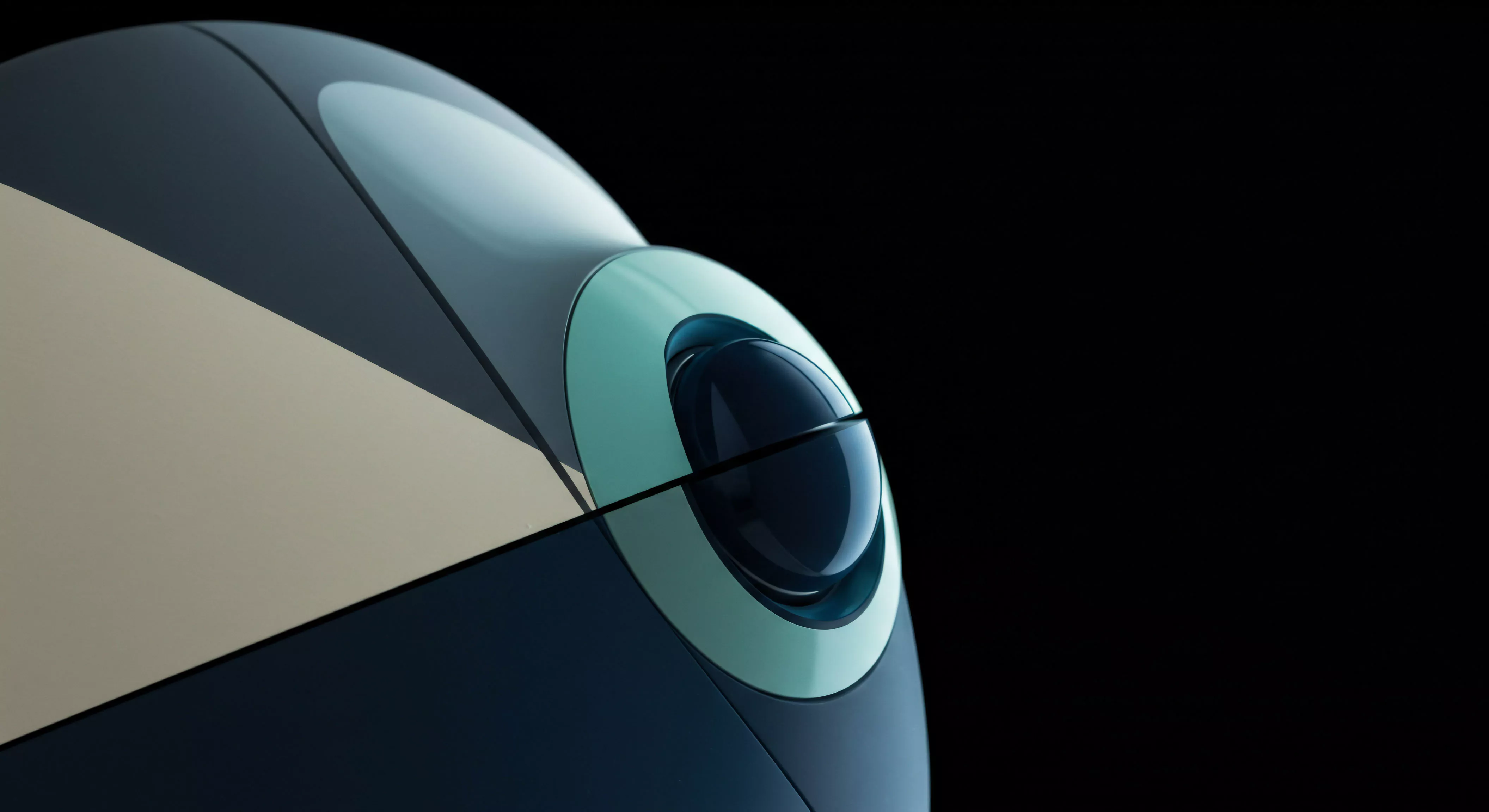

A bank dealer’s capacity to make markets is an extension of its core banking functions ▴ credit extension and balance sheet intermediation. Its ability to absorb risk is directly tied to a massive, diversified balance sheet, which is in turn subject to stringent, capital-intensive banking regulations. The counterparty risk you assume when trading with a bank dealer is therefore a function of the health of this entire, complex institution.

It is a risk profile characterized by deep capital reserves but also by potential opacity, interconnectedness with the broader banking system, and a slower, more deliberate operational tempo. The risk is systemic, institutional, and deeply tied to the macroeconomic environment.

A bank dealer’s risk profile is a function of its vast, regulated balance sheet, creating deep but potentially opaque systemic exposures.

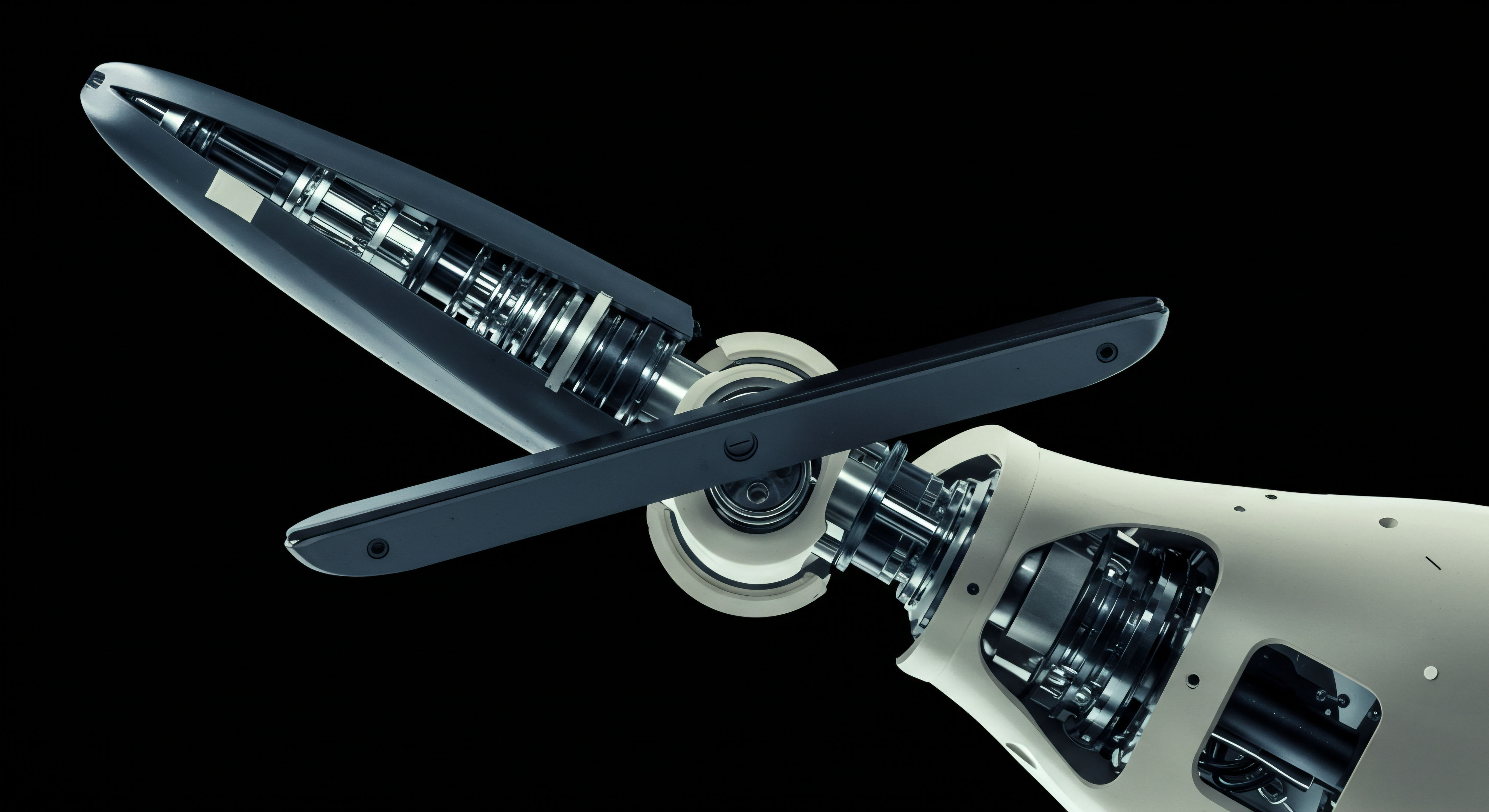

Conversely, an electronic market maker operates on an entirely different architectural model. Its business is not credit extension but high-volume, high-frequency, technologically-driven market-making. EMMs are typically proprietary trading firms, not depository institutions. Their balance sheets are engineered for a specific purpose ▴ to facilitate a high turnover of positions with minimal holding periods.

Capital is deployed to manage short-term settlement and operational risks, not to underwrite long-term credit. The counterparty risk associated with an EMM is therefore a function of its technological infrastructure, its algorithmic performance, and its specific clearing and settlement arrangements. The risk is acute, operational, and concentrated in the mechanics of the trade lifecycle.

Understanding this architectural divergence is the first principle in navigating counterparty risk. The choice is between a deeply capitalized, systemically integrated entity and a technologically advanced, specialized firm. Each presents a distinct set of potential failure points and risk mitigation pathways. The following analysis will deconstruct these differences, providing a systemic framework for evaluating the trade-offs inherent in choosing your counterparty.

What Is the Foundational Difference in Business Models?

The business models of bank dealers and electronic market makers dictate their approach to risk, liquidity provision, and client interaction. A bank dealer’s market-making desk is one component of a larger financial conglomerate. Its primary function is to serve the bank’s clients, which may include corporations, asset managers, and hedge funds, by facilitating their trading needs. This client-centric model means that bank dealers often internalize trades, taking the other side of a client’s position and managing the resulting risk on their own book.

This warehousing of risk is supported by the bank’s substantial capital base and its ability to hedge exposures across different asset classes and markets. The revenue model is based on the bid-ask spread, fees, and the profits generated from managing the warehoused risk.

Electronic market makers, on the other hand, have a much more focused business model. They are technology companies that specialize in providing liquidity to electronic markets. Their goal is to profit from the bid-ask spread by simultaneously posting buy and sell orders for a given security. EMMs do not have a traditional client base; they are market participants that interact with the order book anonymously.

Their strategy relies on speed, sophisticated pricing algorithms, and statistical arbitrage opportunities. They aim to end each trading day with a flat or near-flat position, minimizing their overnight risk. Their revenue is generated from capturing the spread on a massive volume of trades, with each individual trade representing a small profit.

How Does Capital Structure Influence Risk Profiles?

The capital structure of these two types of counterparties is a direct reflection of their business models and regulatory environments. Bank dealers are subject to the stringent capital adequacy requirements of banking regulators like the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. These regulations mandate that banks hold a certain amount of capital as a buffer against unexpected losses. This capital is intended to protect depositors and maintain the stability of the financial system.

The capital of a bank dealer is therefore large, stable, and designed to absorb significant credit and market shocks. This provides a substantial cushion against counterparty default, but it also means that the bank’s capital is supporting a wide range of activities, from commercial lending to investment banking, creating a complex web of interconnected risks.

Electronic market makers, as non-bank institutions, are not subject to the same capital adequacy rules. Their capital is typically private, contributed by partners or shareholders, and is sized to meet the specific requirements of their trading activities. This includes posting margin with clearinghouses and covering potential short-term losses. While the absolute amount of capital may be smaller than that of a bank dealer, it is highly liquid and dedicated solely to the firm’s market-making operations.

The risk for a counterparty is that a sudden, extreme market event could overwhelm the EMM’s capital, leading to a default. However, the absence of a large, leveraged loan book or other banking-related risks means that the EMM’s financial health is more directly tied to its trading performance and less susceptible to broader credit market dislocations.

Strategy

A strategic evaluation of counterparty risk moves beyond the foundational concepts of business models and capital structures to a more granular analysis of specific risk vectors. For the institutional trader, choosing between a bank dealer and an electronic market maker is an exercise in aligning the counterparty’s risk profile with the specific objectives of the trade. The optimal choice depends on factors such as trade size, duration, complexity, and the prevailing market conditions. The strategic framework for this decision involves a multi-faceted assessment of settlement risk, operational resilience, and the impact of regulatory frameworks.

The strategic calculus begins with an analysis of settlement risk. With a bank dealer, particularly in over-the-counter (OTC) markets, settlement can be a bilateral process, with the timing and mechanics governed by a master agreement like the ISDA Master Agreement. While this allows for customized terms, it also creates a direct, and potentially prolonged, credit exposure to the bank. The risk is that the bank defaults before the trade is fully settled.

Mitigation strategies involve the negotiation of collateral agreements, which require the posting of margin to cover potential losses. The effectiveness of these agreements, however, depends on the liquidity of the collateral and the operational efficiency of the margin call process.

Choosing a counterparty is a strategic alignment of the counterparty’s specific risk architecture with the trade’s objectives.

Electronic market makers, by contrast, typically operate in centrally cleared markets. In this model, the central counterparty (CCP) becomes the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer, effectively novating the trade and assuming the settlement risk. The CCP mitigates this risk by requiring all participants, including the EMM, to post margin and contribute to a default fund. This multilateralizes the risk, spreading it across the entire clearing membership.

The strategic advantage is a significant reduction in bilateral counterparty credit risk. The trade-off is a more standardized trading environment with less flexibility in trade terms.

Comparative Analysis of Risk Vectors

To systematically compare the strategic implications of facing a bank dealer versus an EMM, we can deconstruct the risk into several key components. The following table provides a strategic overview of these differences:

| Risk Vector | Bank Dealer | Electronic Market Maker (EMM) |

|---|---|---|

| Credit Risk |

Primary risk vector. Tied to the overall health of the bank’s balance sheet, including its loan portfolio and other investments. Assessed using credit ratings and Credit Default Swap (CDS) spreads. |

Secondary risk vector. Primarily related to short-term settlement obligations. The firm’s creditworthiness is less relevant than its operational integrity and capitalization relative to its trading volume. |

| Settlement Risk |

Can be significant in bilateral OTC trades. Mitigation relies on collateral agreements and the operational capacity to manage margin calls effectively. Exposure duration can be long. |

Largely mitigated by central clearing. The CCP guarantees settlement, reducing bilateral exposure. Risk is concentrated in the CCP’s own default management procedures. |

| Operational Risk |

Stems from complex internal processes, legacy technology, and potential for human error in large, bureaucratic organizations. Failure points can be opaque. |

Stems from technology and algorithms. Risks include system outages, connectivity issues, and algorithmic errors that could lead to erroneous trades or a sudden withdrawal of liquidity. |

| Regulatory Environment |

Subject to stringent banking regulations (e.g. Basel III), which impose high capital requirements and oversight. This provides a buffer but can also constrain risk appetite. |

Subject to securities regulations (e.g. by the SEC or ESMA), which focus on market integrity and conduct. Capital requirements are typically lower and more directly tied to trading risk. |

| Liquidity Provision |

Often relationship-based. Can provide deep liquidity for large, complex, or illiquid trades. May be less competitive on standard, high-volume products. |

Algorithmic and anonymous. Provides tight spreads and high volumes for liquid, standardized products. May reduce liquidity during times of extreme market stress. |

What Are the Implications of Regulatory Arbitrage?

The divergent regulatory landscapes for bank dealers and EMMs create opportunities for strategic positioning and potential arbitrage. Bank dealers operate under a prudential regulatory framework designed to ensure the stability of the entire financial system. This involves significant compliance costs and capital charges for holding risky assets, including uncleared derivatives.

These costs are ultimately passed on to clients in the form of wider spreads or fees. An institution trading with a bank dealer is implicitly paying for the systemic stability provided by this regulatory umbrella.

EMMs, being regulated as securities firms rather than banks, face a different set of rules. Their regulations are focused on fair and orderly markets, investor protection, and the management of market risk. While still robust, these regulations are generally less burdensome in terms of capital requirements for market-making activities.

This lower regulatory overhead allows EMMs to operate on thinner margins and offer more competitive pricing for standardized, centrally cleared products. The strategic consideration for a trader is whether the pricing benefits of trading with an EMM outweigh the potential for higher risk in a systemic crisis, where the deep capital buffer of a bank dealer might prove decisive.

- Bank Dealer Regulation Governed by banking authorities (e.g. Federal Reserve, ECB). Focus on solvency, systemic risk, and depositor protection. High capital requirements under Basel III/IV frameworks. Subject to stress testing (e.g. CCAR in the U.S.).

- EMM Regulation Governed by securities regulators (e.g. SEC, ESMA). Focus on market conduct, transparency, and operational integrity. Capital requirements are based on net capital rules (e.g. SEC Rule 15c3-1), which are more directly linked to the risk of trading positions.

- Strategic Impact The choice of counterparty can be a strategic decision to optimize for either regulatory security or pricing efficiency. For large, complex OTC derivatives, the regulatory framework of a bank dealer may be preferred. For high-volume, standardized futures or equities, the efficiency of an EMM may be more attractive.

Execution

The execution of a counterparty risk management strategy requires a transition from strategic comparison to quantitative analysis and operational protocol. For a sophisticated trading desk, managing counterparty risk is an active, data-driven process. It involves the continuous measurement of exposure, the implementation of robust mitigation techniques, and a clear understanding of the legal and operational mechanics of default. The execution framework differs significantly when dealing with bank dealers versus electronic market makers, reflecting their distinct architectures.

When executing trades with a bank dealer, particularly in the OTC space, the cornerstone of risk management is the Credit Value Adjustment (CVA). CVA is the market price of counterparty credit risk and represents the discount to the value of a derivative portfolio to account for the possibility of the counterparty’s default. Calculating CVA is a complex quantitative exercise that requires three key inputs ▴ the probability of default (PD) of the counterparty, the loss given default (LGD), and the expected future exposure (EFE) to the counterparty. The trading desk must have the systems and models in place to calculate CVA for each bank dealer counterparty and to monitor it in real-time as market conditions change.

Effective counterparty risk management is an active, quantitative process of measurement, mitigation, and operational readiness.

Executing with an EMM in a centrally cleared environment shifts the focus of risk management from bilateral credit analysis to the operational integrity of the clearing process. The primary tool for risk mitigation is the margin system of the central counterparty. The trading desk’s responsibility is to ensure that it has sufficient capital and liquidity to meet all margin calls from the CCP, even in times of market stress. This involves sophisticated liquidity management and forecasting.

The risk of the EMM’s default is socialized through the CCP’s waterfall of default resources, which includes the EMM’s initial margin, its contribution to the default fund, the CCP’s own capital, and the remaining default fund contributions of other clearing members. The execution challenge is to understand the CCP’s rules and procedures and to assess the adequacy of its default waterfall.

The Operational Playbook for Risk Mitigation

A robust operational playbook for managing counterparty risk must be tailored to the specific type of counterparty. It should be a clear, actionable set of procedures that are regularly tested and updated.

- Counterparty Onboarding and Limit Setting

- Bank Dealers Perform in-depth credit analysis, reviewing financial statements, credit ratings, and CDS spreads. Establish a maximum exposure limit based on this analysis. This limit should be a function of the bank’s credit quality and the trading desk’s risk appetite. The legal team must negotiate an ISDA Master Agreement with a robust Credit Support Annex (CSA) that specifies collateral types, haircuts, and margin call thresholds.

- Electronic Market Makers The focus is on operational due diligence. Assess the EMM’s technology platform, latency, and uptime. Review its clearing arrangements and its history of performance during periods of market volatility. Limits may be set based on volume or the number of open positions rather than on a traditional credit assessment.

- Exposure Monitoring and Measurement

- Bank Dealers Implement a system for calculating Potential Future Exposure (PFE) and CVA on a daily basis. This requires sophisticated Monte Carlo simulation models that can project future market movements and their impact on the value of the derivative portfolio. The system must aggregate exposures across all trades with a given counterparty.

- Electronic Market Makers Exposure is primarily monitored through the margin requirements of the CCP. The trading desk must have a real-time view of its initial and variation margin obligations. The risk is less about the EMM’s creditworthiness and more about the liquidity risk of having to meet sudden, large margin calls.

- Collateral Management

- Bank Dealers Operate a highly efficient collateral management process. This includes issuing and responding to margin calls in a timely manner, valuing collateral accurately, and managing disputes. The process must be able to handle a high volume of calls during a market crisis. The firm must also manage the concentration risk of the collateral it receives.

- Electronic Market Makers Collateral management is largely handled by the CCP. The trading desk’s responsibility is to ensure it has a sufficient pool of eligible collateral (cash, government bonds) to post to the CCP. This may involve setting up dedicated credit lines or securities lending facilities.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

The quantitative modeling of counterparty risk provides the analytical foundation for setting limits and pricing trades. The following table illustrates a simplified CVA calculation for a hypothetical interest rate swap with a bank dealer, and a comparison with the margin-based exposure to an EMM for a similar, exchange-traded interest rate future.

| Parameter | Bank Dealer (OTC Swap) | Electronic Market Maker (Cleared Future) |

|---|---|---|

| Notional Amount |

$100,000,000 |

$100,000,000 |

| Primary Risk Metric |

Credit Value Adjustment (CVA) |

Initial Margin (IM) |

| Probability of Default (1-year) |

1.5% (derived from CDS market) |

N/A (Risk transferred to CCP) |

| Loss Given Default (LGD) |

60% (standard assumption for unsecured debt) |

N/A (Losses covered by CCP waterfall) |

| Expected Future Exposure (EFE) |

$1,200,000 (from Monte Carlo simulation) |

N/A |

| Calculated CVA |

CVA = EFE PD LGD = $1,200,000 0.015 0.60 = $10,800 |

N/A |

| Initial Margin Requirement |

Determined by bilateral CSA (e.g. $500,000 threshold) |

$2,500,000 (Calculated by CCP’s SPAN or VaR model) |

| Primary Risk Management Focus |

Modeling EFE and PD; managing collateral. |

Liquidity management to meet margin calls. |

This simplified model demonstrates the fundamental difference in the execution of risk management. For the bank dealer, the focus is on quantifying and pricing the long-term credit risk of the counterparty. For the EMM, the focus is on the short-term liquidity risk associated with posting collateral to the CCP.

The CVA of $10,800 represents the economic cost of the bank dealer’s counterparty risk, which would be factored into the price of the swap. The $2,500,000 initial margin for the cleared future is not a cost, but a deposit that collateralizes the position and protects the system from default.

References

- Arora, N. Gandhi, P. & Longstaff, F. A. (2021). Counterparty Risk and Counterparty Choice in the Credit Default Swap Market. The Review of Financial Studies, 35(3), 1339 ▴ 1382.

- Duffie, D. & Zhu, H. (2011). Does a Central Clearing Counterparty Reduce Counterparty Risk?. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 1(1), 74 ▴ 95.

- Gündüz, Y. (2015). Dealer-specific funding costs and the cross-section of CDS spreads. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(2), 374-391.

- Hull, J. C. (2018). Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives (10th ed.). Pearson.

- Financial Stability Board. (2010). Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments ▴ Initial Considerations.

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. (2014). The standardised approach for measuring counterparty credit risk exposures. Bank for International Settlements.

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2013). SEC Adopts Rules for Cross-Border Security-Based Swaps, Amends Definition of U.S. Person.

- Cont, R. & Minca, A. (2016). Credit Default Swaps and the Emergence of Systemic Risk. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics, 7(1), 693-730.

- Allen, F. & Gale, D. (2000). Financial contagion. Journal of Political Economy, 108(1), 1-33.

- O’Hara, M. (1995). Market Microstructure Theory. Blackwell Publishers.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Risk Architecture

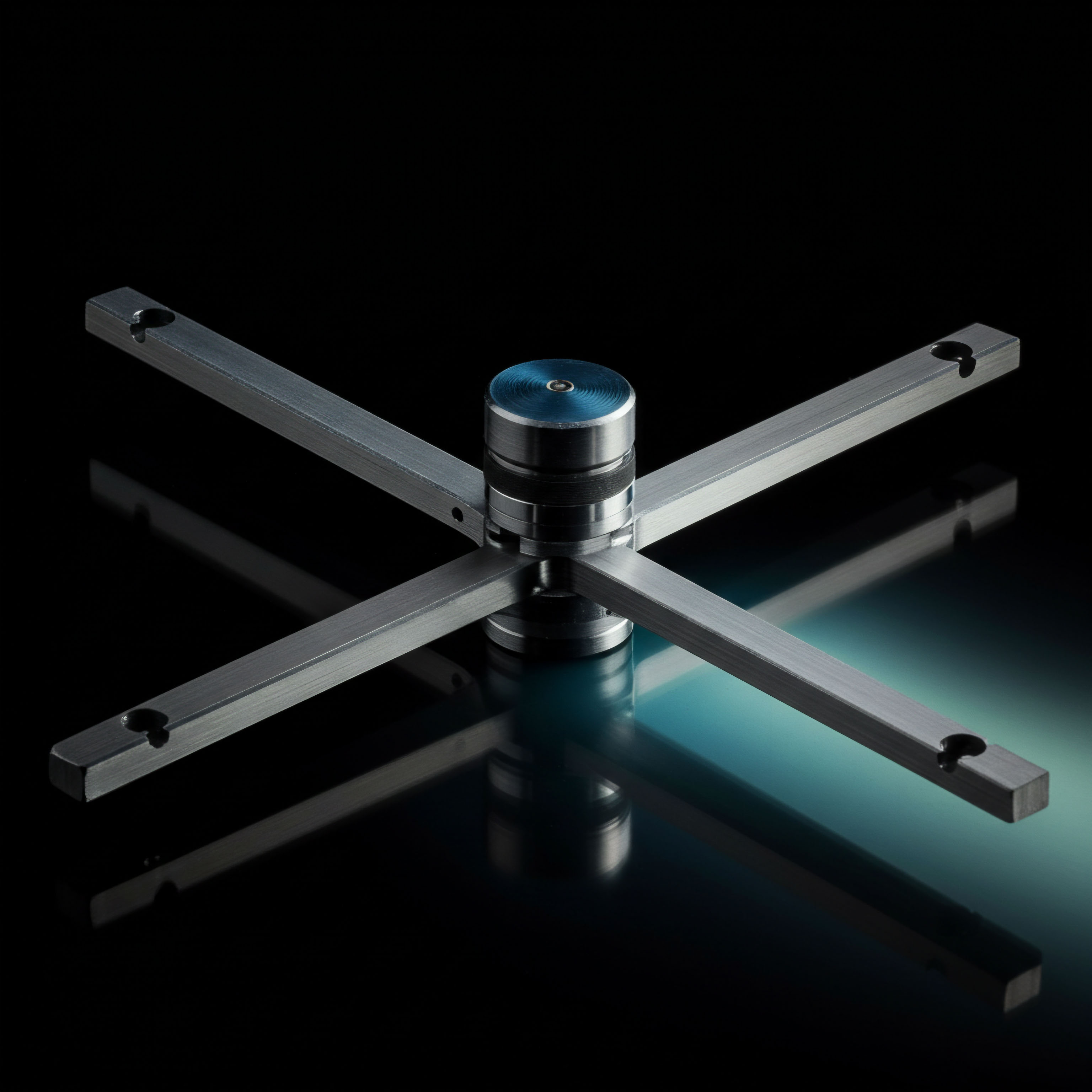

The analysis of counterparty risk, when deconstructed to its core architectural components, ceases to be a simple question of “who is safer.” It becomes a far more sophisticated inquiry into the nature of your own operational framework. The knowledge of how a bank dealer’s systemic depth contrasts with an electronic market maker’s technological acuity is a critical input. The truly resilient trading enterprise views this choice not as a static decision but as a dynamic calibration. Your institutional strategy dictates the required risk profile for each trade, each portfolio, each mandate.

The question you must now consider is whether your internal systems for measurement, mitigation, and execution are sufficiently advanced to interface optimally with both of these divergent architectures. A superior edge is achieved when your own operational system is engineered with the precision to select the right counterparty, for the right reason, at the right time.

Glossary

Electronic Market Maker

Counterparty Risk

Balance Sheet

Bank Dealer

Risk Profile

Electronic Market

Risk Mitigation

Electronic Market Makers

Bank Dealers

Market Makers

Settlement Risk

Market Maker

Isda Master Agreement

Otc

Default Fund

Ccp

Counterparty Credit Risk

Credit Default Swap

Risk Vector

Margin Calls

Central Clearing

Capital Requirements

Systemic Risk

Counterparty Risk Management

Trading Desk

Credit Value Adjustment

Loss Given Default

Risk Management

Initial Margin

Cds Spreads

Cva