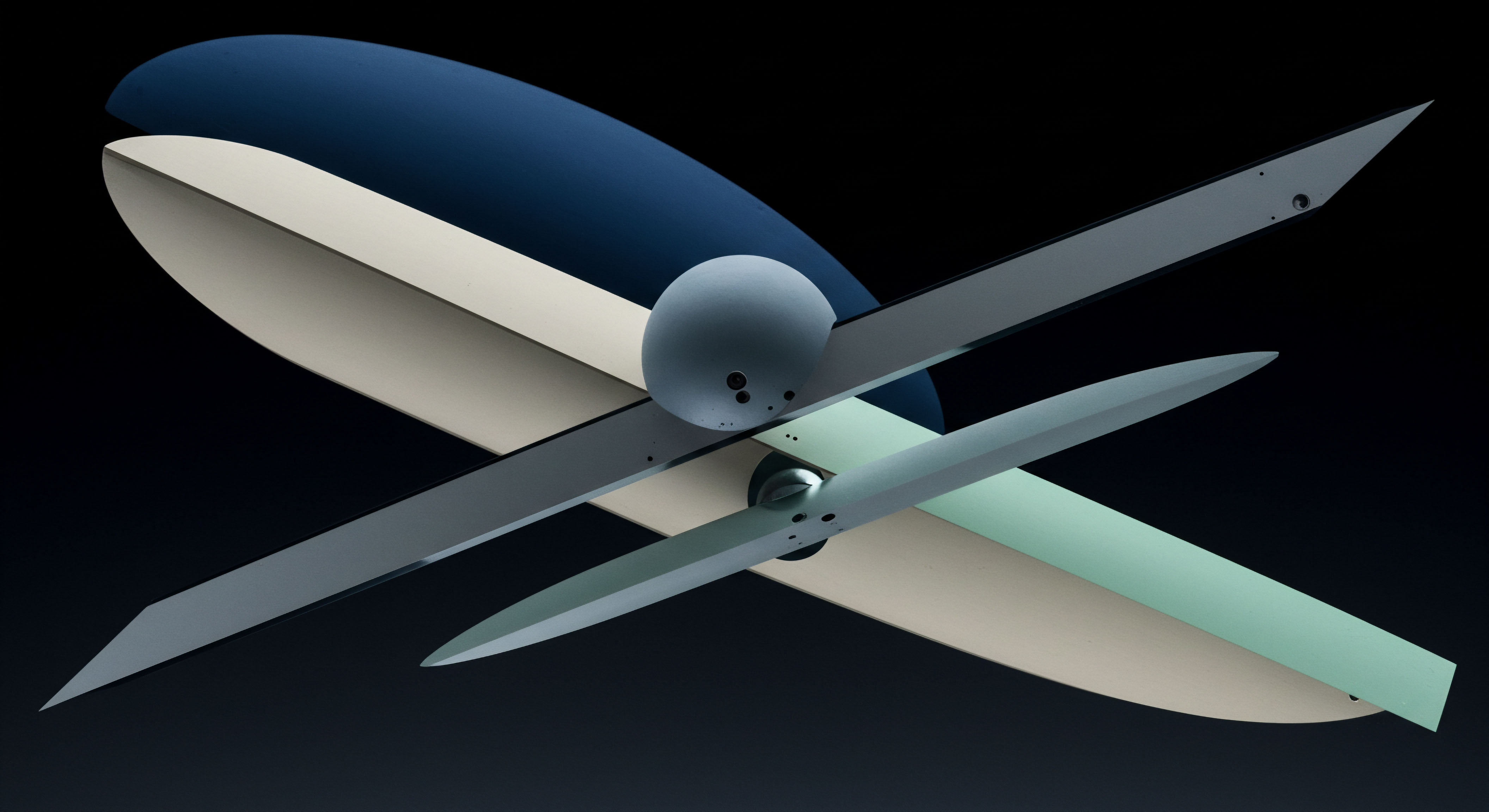

Concept

The architecture of risk within a central clearinghouse (CCP) rests upon a foundational decision regarding the calculation and collection of initial margin. This decision dictates the precise boundary between individual responsibility and collective liability. The choice between a gross or net margining model is a determination of how risk is quantified, segregated, and, ultimately, mutualized across the ecosystem of clearing members.

It defines the system’s first line of defense against a member default and establishes the conditions under which the default fund, the ultimate backstop of shared resources, is accessed. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to grasping the economic and operational realities of centrally cleared markets.

Gross margining operates on a principle of direct and unmitigated liability. In this model, a clearing member is required to post initial margin to the CCP that represents the sum of the margin requirements for each of its individual clients. There is no allowance for offsetting positions between different clients within the clearing member’s portfolio. For instance, if one client holds a long position of 100 contracts and another client holds a short position of 100 identical contracts, the clearing member must deliver the full margin required for both the 100 long and 100 short positions to the CCP.

This system creates a transparent and robust buffer of collateral directly tied to specific client activity. The risk of each client is, in essence, individually collateralized at the CCP level, creating a formidable barrier against contagion from a single client’s failure.

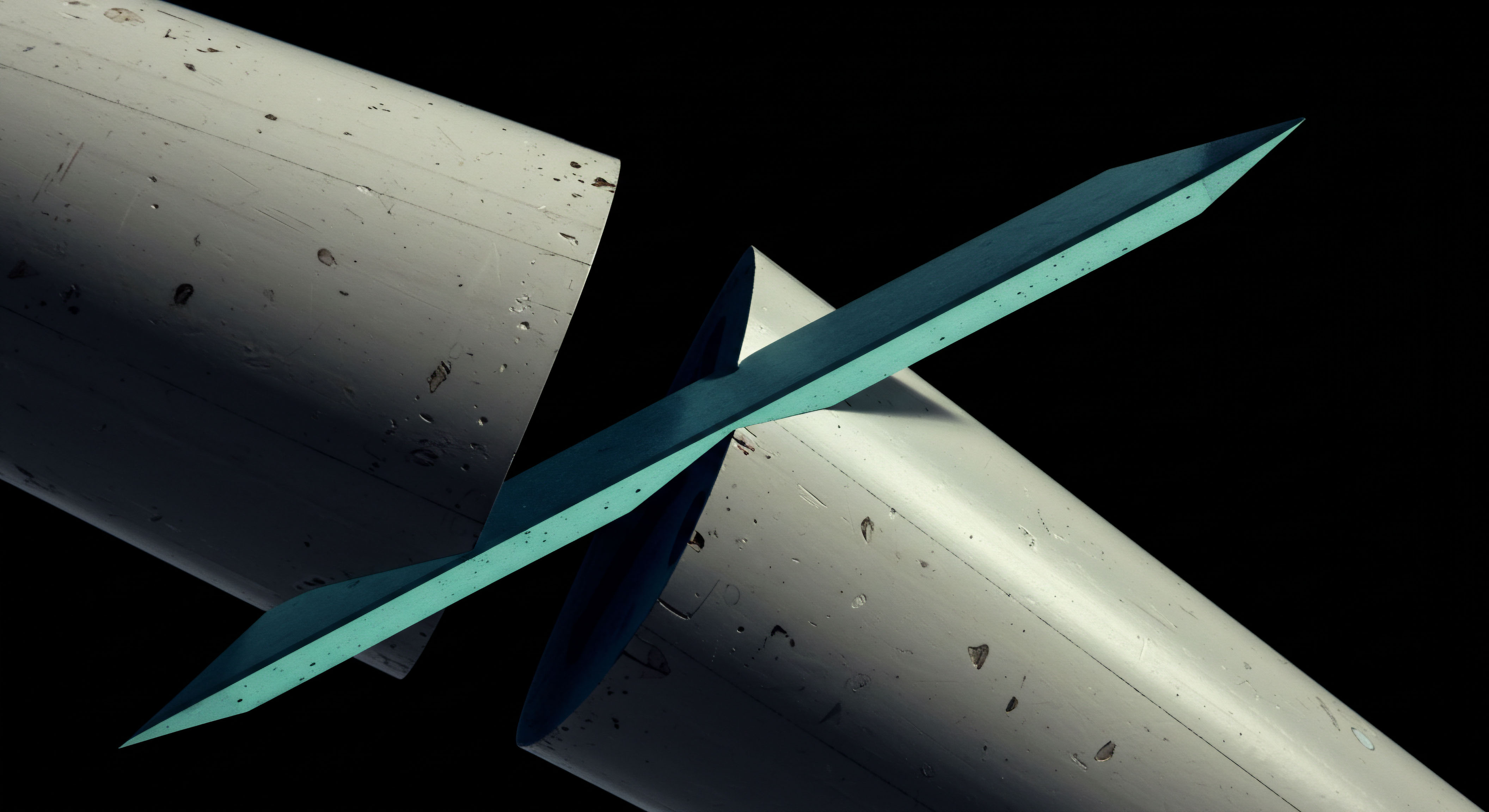

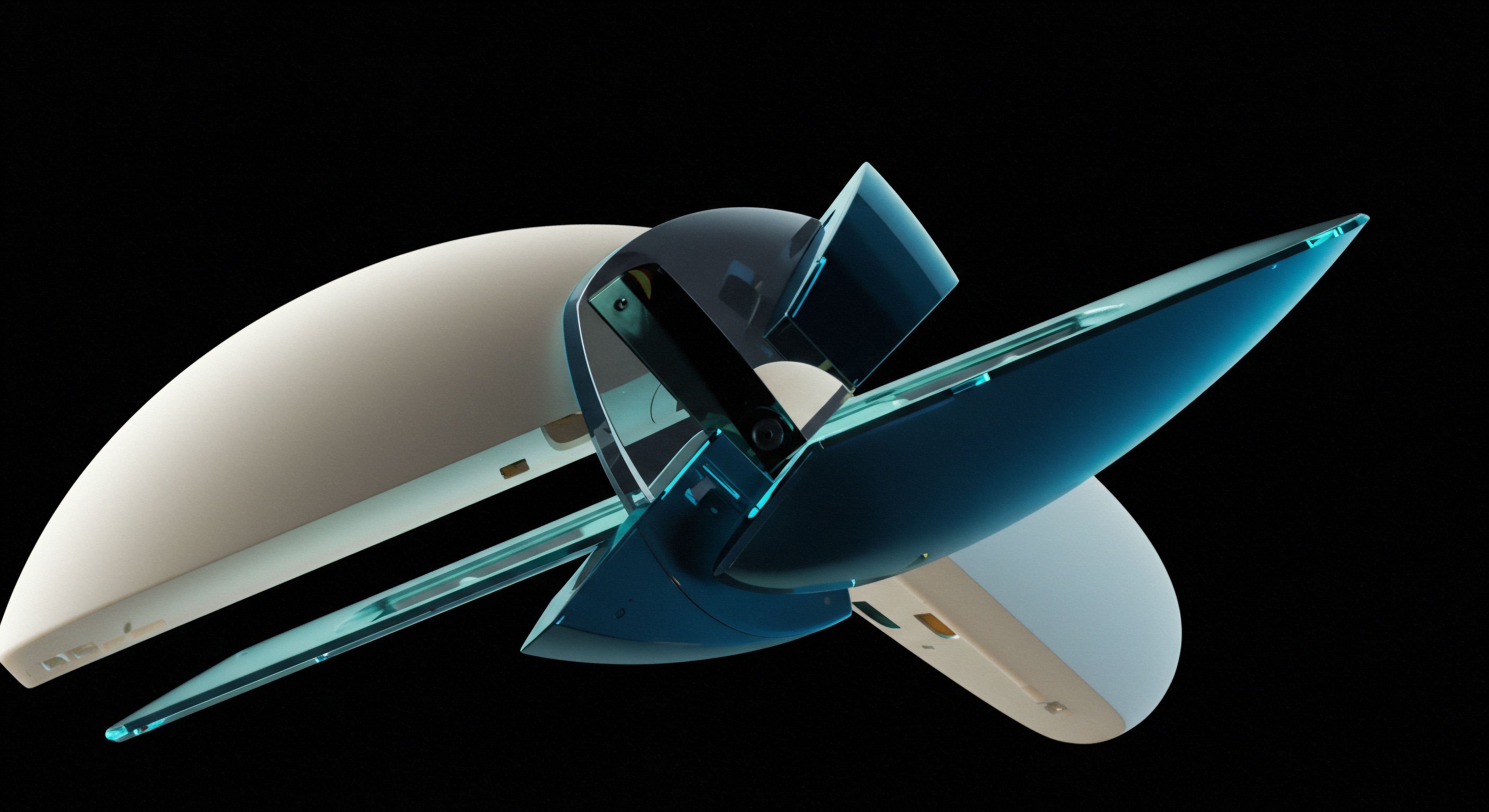

The gross margining model isolates and collateralizes risk on a client-by-client basis, preventing the positions of one client from offsetting another’s.

Conversely, net margining functions on a portfolio basis. This model permits a clearing member to offset the positions of its various clients when calculating its total margin obligation to the CCP. Using the prior example, the clearing member’s requirement for the two clients with perfectly offsetting long and short positions would be zero. The CCP collects margin based on the net exposure of the clearing member’s entire client portfolio.

This approach is predicated on the statistical reality that a diversified portfolio of positions presents less aggregate risk than the simple sum of its parts. It provides significant capital efficiency for the clearing member, as less collateral is required to be posted to the CCP. This efficiency, however, alters the structure of the CCP’s risk defenses, making the default fund a more proximate layer of protection in certain default scenarios.

Risk mutualization refers to the process by which losses exceeding the resources of a defaulting member are shared among the surviving clearing members. This is primarily facilitated through the default fund, a pool of capital contributed by all clearing members. The choice of margining model directly influences the probability of accessing this mutualized fund. A gross margining system erects a higher wall of individualized collateral that must be breached before the shared resources of the default fund are touched.

A net margining system results in a comparatively lower wall of initial margin, meaning a default by a large, directional client could exhaust the clearing member’s net margin and its own contributions more quickly, thereby escalating the event toward the mutualized fund. The two models present a fundamental trade-off between the capital efficiency afforded to clearing members and the level of pre-funded, individualized protection available to the CCP.

Strategy

The selection of a margining model is a core strategic decision for a central counterparty, reflecting its philosophical approach to risk management, its commercial objectives, and the regulatory environment in which it operates. This choice creates a cascade of strategic implications for clearing members, influencing their funding costs, operational complexity, and competitive positioning. The models are not merely technical calculations; they are blueprints for allocating risk and capital throughout the clearing ecosystem.

CCP Strategic Frameworks

A CCP’s decision to implement a gross or net margining system is driven by its overarching risk tolerance and business strategy. These strategies are often shaped by regional market practices, with North American and APAC CCPs historically favoring gross models, while EMEA-based CCPs have often utilized net models.

The Fortress Strategy of Gross Margining

A CCP that adopts a gross margining model prioritizes the maximization of pre-funded resources as its primary defense. This strategy is built on the principle of minimizing the probability of ever needing to access the mutualized default fund. By requiring margin for every client position without offset, the CCP ensures that the initial margin layer is as robust as possible. This approach provides the CCP with exceptional transparency into the risk profiles of its clearing members’ underlying clients.

It can identify concentrated positions at the client level, even if those positions are offset by other clients within the same clearing member. This granular view allows for more precise risk management and intervention. The strategic trade-off is a potential reduction in the CCP’s competitiveness, as the higher margin requirements increase the cost of clearing for its members and their end clients.

The Capital Efficiency Strategy of Net Margining

A CCP employing a net margining model is strategically focused on providing a more capital-efficient clearing service. By allowing clearing members to net their client positions, the CCP reduces the aggregate margin requirement, lowering the cost of participation. This can attract more clearing volume, particularly from members with large, diversified client bases. This strategy relies heavily on the law of large numbers and portfolio theory, assuming that the net exposure of a member’s portfolio is a more accurate measure of the CCP’s true risk than the gross sum of its parts.

The strategic compromise is a greater reliance on the subsequent layers of the default waterfall. The CCP accepts a thinner initial margin buffer in exchange for market growth, with the understanding that a significant, directional client default could more rapidly lead to the use of mutualized resources.

Clearing Member Strategic Responses

Clearing members must adapt their own strategies to the margining model of the CCPs they use. This affects not only their treasury operations but also their client service models and profitability.

- Operations Under Gross Margining A clearing member operating under a gross margining regime faces higher direct funding costs. It cannot use the collateral from one client to satisfy the margin requirement of another at the CCP level. This necessitates a more sophisticated and costly treasury function to manage collateral, potentially sourcing liquidity to meet margin calls for a large client even if another client has an offsetting position. The strategic focus for the member becomes efficient collateral transformation and optimization to minimize the drag on its balance sheet.

- Opportunities Under Net Margining For a clearing member, a net margining system presents a significant strategic opportunity. The clearing member typically collects margin from its clients on a gross basis, as required by its own risk management policies. When the CCP calculates the member’s obligation on a net basis, a surplus of collateral is often created at the clearing member level. This surplus can be reinvested to generate net interest income (NII), turning the member’s risk management function into a potential profit center. This dynamic can create intense competition among clearing members to attract clients with offsetting flow to maximize their netting benefits.

How Does the Margin Period of Risk Interact with Model Choice?

The Margin Period of Risk (MPOR) is the time, typically measured in days, that a CCP estimates it would take to liquidate a defaulting member’s portfolio. A longer MPOR results in a higher initial margin requirement. Some CCPs have historically used a longer MPOR, such as two days, in conjunction with net margining as a way to compensate for the leniency of the netting system.

A one-day MPOR with gross margining might be considered equivalent in protection to a two-day MPOR with net margining under certain conditions. The effectiveness of this trade-off, however, depends heavily on the distribution and concentration of client positions within a clearing member’s portfolio.

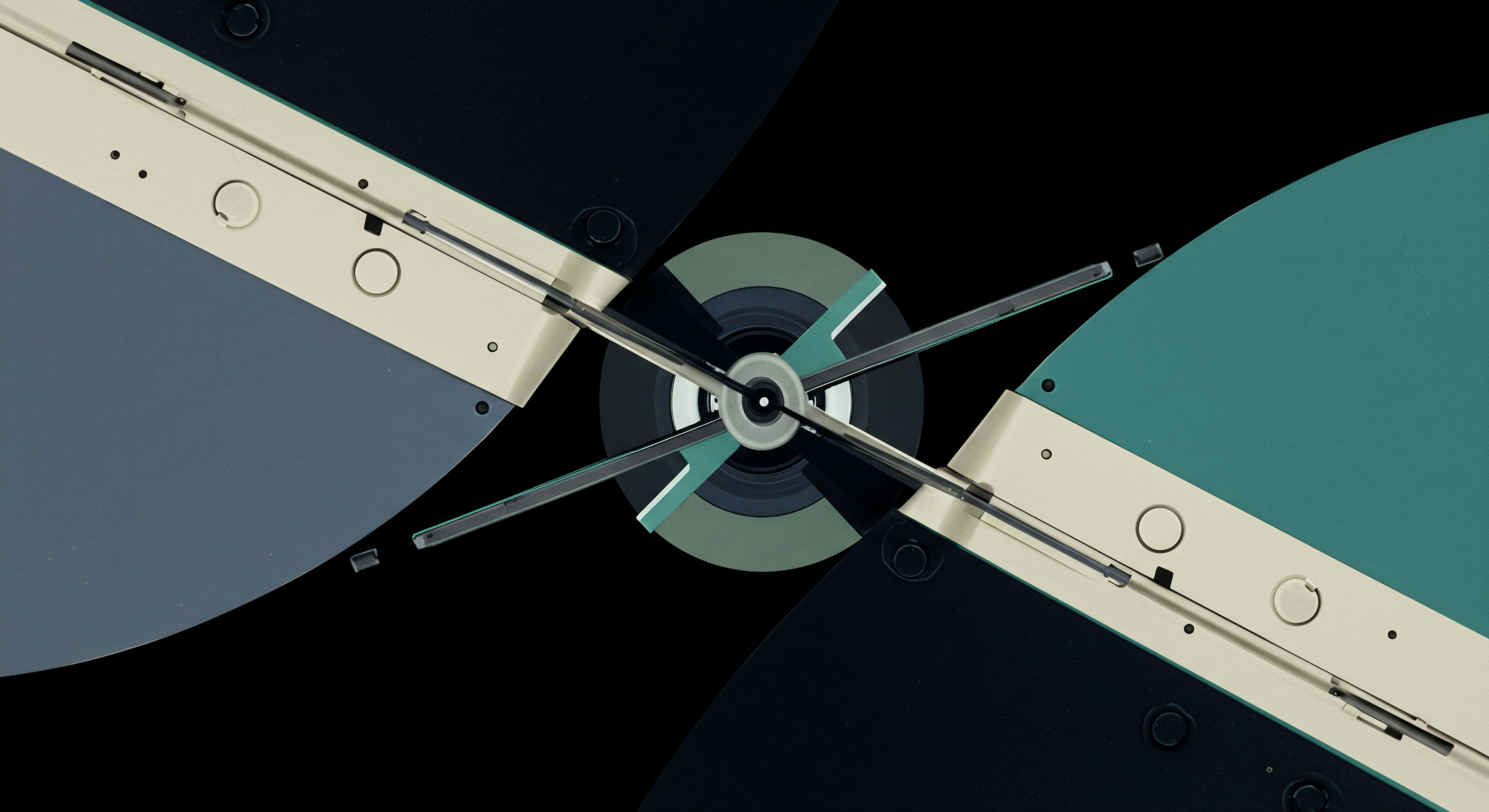

The table below outlines the primary strategic differences between the two models from the perspective of the entire clearing system.

| Strategic Dimension | Gross Margining Model | Net Margining Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Maximizing CCP resilience; minimizing use of mutualized resources. | Maximizing capital efficiency for clearing members; attracting volume. |

| CCP Risk Buffer | Very large initial margin layer; high level of pre-funded protection. | Smaller initial margin layer; greater reliance on portfolio diversification. |

| Transparency of Risk | High transparency into individual client risk concentrations. | Opaque view of underlying client risks; focus is on the net portfolio. |

| Reliance on Default Fund | Low. A default is less likely to breach the initial margin layer. | Higher. A large client default can more readily expose the default fund. |

| Clearing Member Cost | High funding and collateral costs. | Low funding costs; potential for revenue from collateral surplus. |

| Systemic Concern | Potentially higher costs could reduce clearing adoption. | Risk of a sudden, large loss in a concentrated client default. |

Execution

The theoretical and strategic differences between gross and net margining manifest in the precise operational mechanics of the CCP’s default waterfall. This sequence of pre-defined resources is the execution protocol for managing a clearing member failure. The choice of margining model fundamentally alters the composition and depth of the initial layers of this waterfall, which in turn dictates the speed and probability of escalating to the mutualized layers.

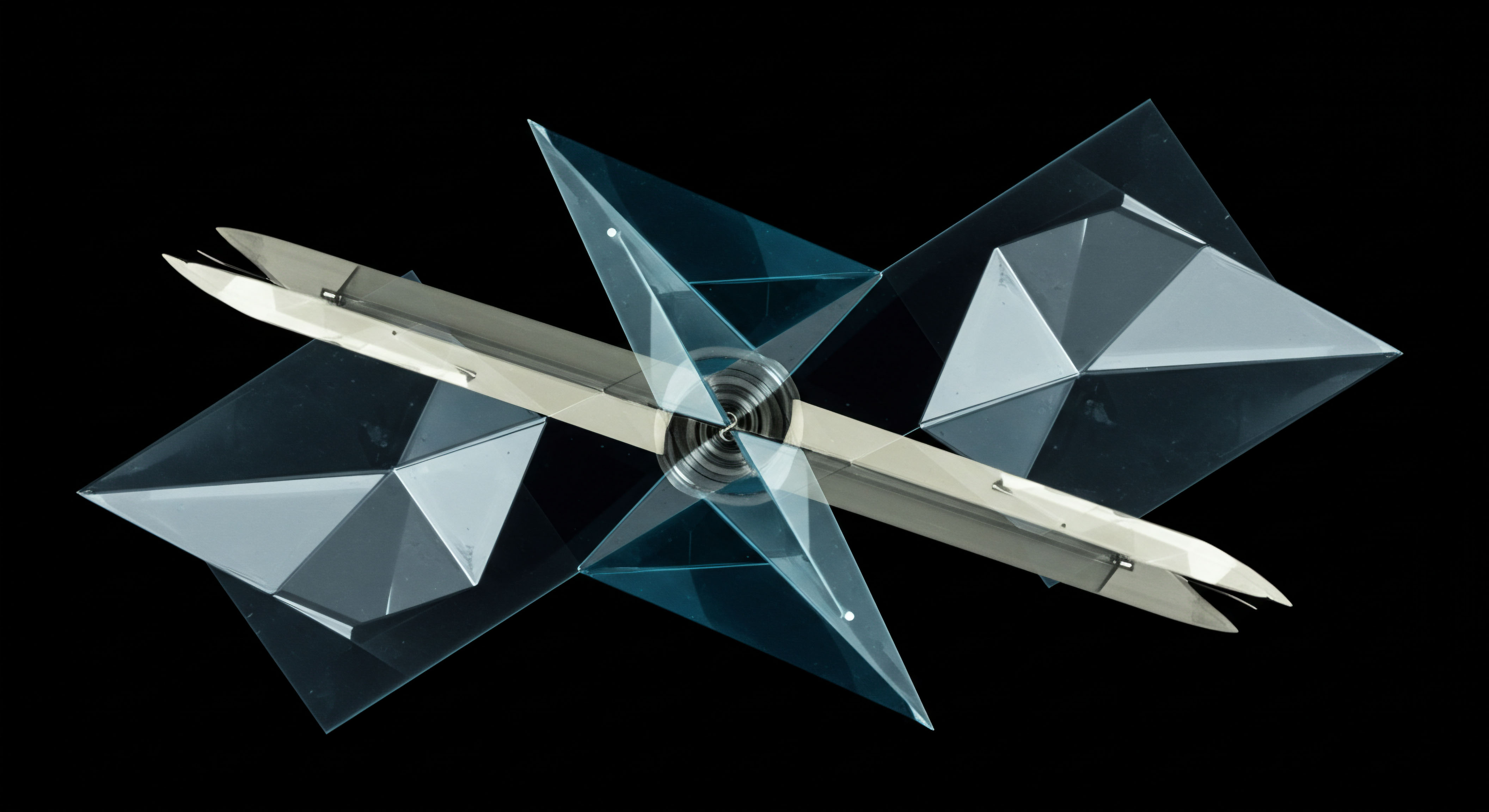

The Default Waterfall Architecture

A CCP’s default waterfall is a multi-layered defense system designed to absorb losses from a defaulting clearing member in a specific, predetermined order. This ensures a predictable and orderly process during a crisis. The typical layers are:

- Initial Margin The collateral posted by the defaulting member to cover potential future losses on its portfolio. This is the first line of defense.

- Defaulting Member’s Default Fund Contribution The defaulting member’s own contribution to the mutualized guarantee fund is used next.

- CCP’s “Skin-in-the-Game” (SITG) A portion of the CCP’s own capital is put at risk to align its incentives with those of the clearing members.

- Surviving Members’ Default Fund Contributions This is the truly mutualized layer, where the contributions of the non-defaulting members are used to cover any remaining losses.

- Further Loss Allocation Tools In extreme, uncovered loss scenarios, CCPs may have additional powers, such as levying further assessments on surviving clearing members.

Execution under a Default Scenario a Comparative Analysis

The execution of the default waterfall diverges significantly depending on the margining model in place. Let us consider a clearing member with two clients, Client A (long 1,000 contracts) and Client B (short 950 contracts). The initial margin per contract is $100.

Execution with Gross Margining

Under a gross model, the clearing member’s initial margin requirement is calculated as the sum of the requirements for each client.

- Client A Margin 1,000 contracts $100/contract = $100,000

- Client B Margin 950 contracts $100/contract = $95,000

- Total CCP Requirement $100,000 + $95,000 = $195,000

The clearing member must post $195,000 to the CCP. Now, assume Client A defaults, and its position loses $120,000. The CCP seizes the initial margin posted for Client A’s account group. In this case, the $100,000 margin covers a substantial portion of the loss.

The remaining $20,000 loss would then be covered by the clearing member’s other resources or its contribution to the default fund. The key is that a large, specific buffer was available for the specific source of the risk. The positions of Client B are segregated and unaffected.

Execution with Net Margining

Under a net model, the clearing member’s requirement is based on the net position.

- Net Position 1,000 long – 950 short = 50 long contracts

- Total CCP Requirement 50 contracts $100/contract = $5,000

The clearing member posts only $5,000 to the CCP. While the clearing member would have collected the full $195,000 from its clients, it retains the $190,000 surplus. If Client A defaults with the same $120,000 loss, the CCP seizes the posted $5,000 in initial margin. This leaves an immediate, uncovered loss of $115,000.

This loss must be covered by the clearing member’s own default fund contribution and potentially the CCP’s SITG. If those are insufficient, the loss immediately spills over to the mutualized default fund contributions of all other clearing members. The capital efficiency gained by the member translates directly into a much faster path to risk mutualization in a client default.

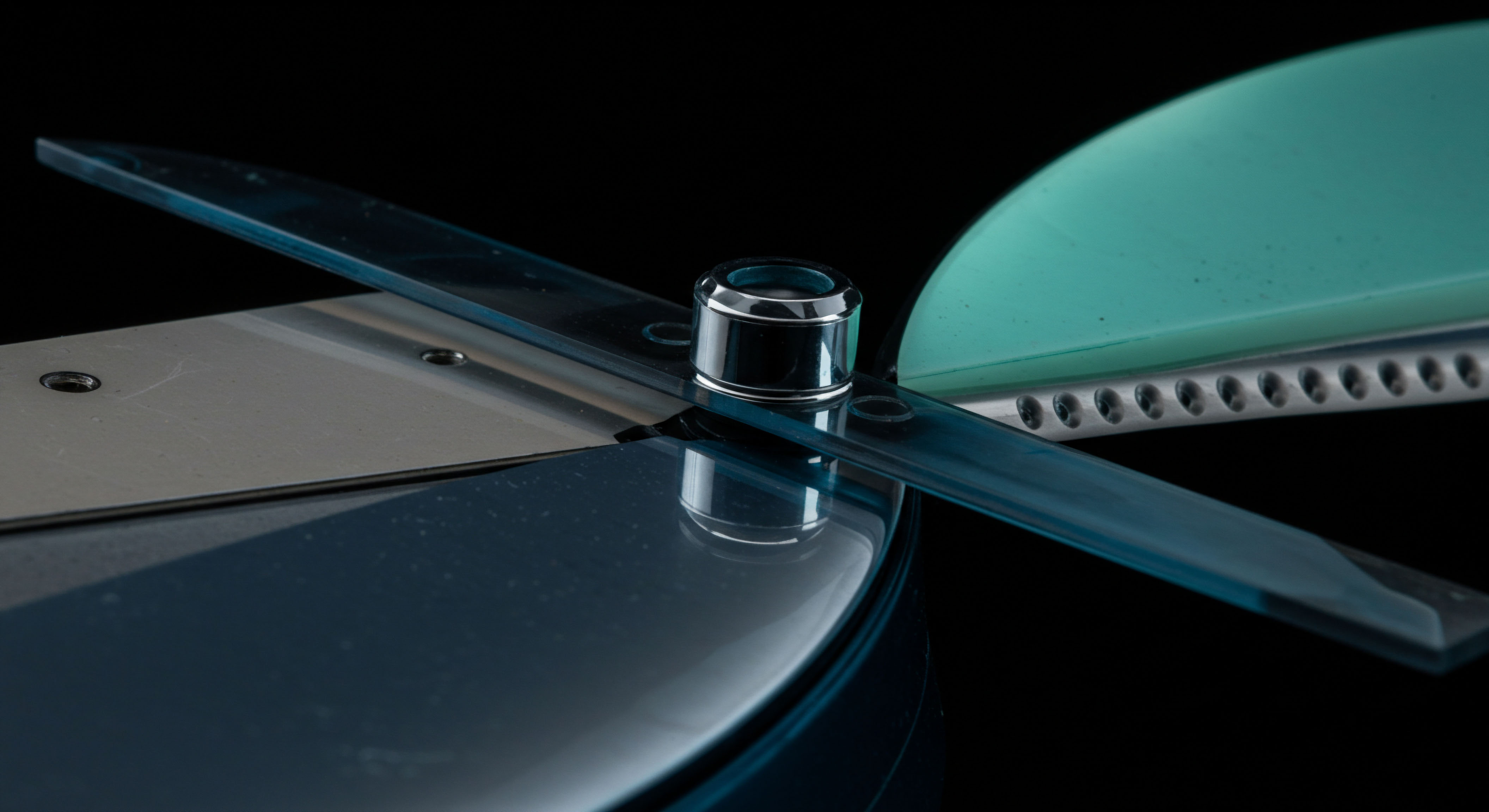

Net margining provides capital efficiency at the cost of a thinner initial defense, accelerating the potential use of shared resources in a default.

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the two execution paths in this hypothetical default scenario.

| Execution Step | Gross Margining Protocol | Net Margining Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Margin Posted to CCP | $195,000 | $5,000 |

| Client A Defaults (Loss of $120,000) | Loss is incurred on the specific client position. | Loss is incurred on the specific client position. |

| Step 1 Use Initial Margin | CCP uses the $100,000 posted for Client A. | CCP uses the entire $5,000 net margin posted by the member. |

| Remaining Loss after IM | $20,000 | $115,000 |

| Step 2 Use Member’s Default Fund Contribution | The $20,000 loss is covered by the member’s contribution. | The $115,000 loss depletes the member’s contribution. |

| Exposure to Mutualized Fund | Zero or minimal exposure. The loss is contained. | High probability of significant exposure and loss mutualization. |

What Are the System Integration Consequences?

The operational and technological architecture required to support each model differs. Gross margining demands robust systems capable of tracking positions, margins, and collateral on a granular, per-client-account basis. This requires significant investment in technology for segregation and reporting. Net margining is less demanding from a data segregation standpoint at the CCP level but requires the clearing member to have sophisticated internal risk systems.

The member must be able to manage the risks of its entire portfolio, knowing that the CCP’s margin requirement only reflects its net exposure and may hide significant underlying concentration risks. For firms seeking to optimize their collateral, real-time visibility into balances, obligations, and CCP eligibility rules across both models is a critical technological requirement.

References

- Steigerwald, Robert S. “Cleared margin setting at selected CCPs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 2013.

- Shreenivas, K. and M. R. Singh. “Choice of margin period of risk and netting for computing margins in central counterparty clearinghouses ▴ a Monte Carlo investigation.” Journal of Financial Market Infrastructures, vol. 10, no. 4, 2022.

- Raymond, Ragu. “Maximising Collateral Margin Efficiency ▴ Gross vs Net.” Baton Systems, 16 Aug. 2023.

- Szanyi, Gergely, et al. “Risk Mutualization in Central Clearing ▴ An Answer to the Cross-Guarantee Phenomenon from the Financial Stability Viewpoint.” MDPI, vol. 12, no. 11, 2020.

- Pirrong, Craig. “A ‘Bill of Goods’ ▴ CCPs and Systemic Risk.” Capital Markets, 2014.

Reflection

The analysis of gross versus net margining moves beyond a simple accounting exercise. It compels an institution to define its own position within the complex system of central clearing. The knowledge of these mechanics is a component of a larger intelligence framework. The critical question becomes how your own operational architecture, capital strategy, and risk appetite align with the realities of each model.

Does your firm’s system prioritize the capital efficiency of netting, and are you prepared for the accelerated risk escalation it implies? Or does it favor the transparent, albeit costly, fortress of gross margining? The optimal path is a function of an institution’s specific blueprint for navigating the interconnected landscape of modern financial markets. The ultimate strategic edge lies in constructing an operational framework that not only understands these rules but is designed to master them.

Glossary

Clearing Members

Margining Model

Default Fund

Gross Margining

Clearing Member

Net Margining

Capital Efficiency

Risk Mutualization

Initial Margin

Risk Management

Initial Margin Layer

Margin Requirement

Default Waterfall