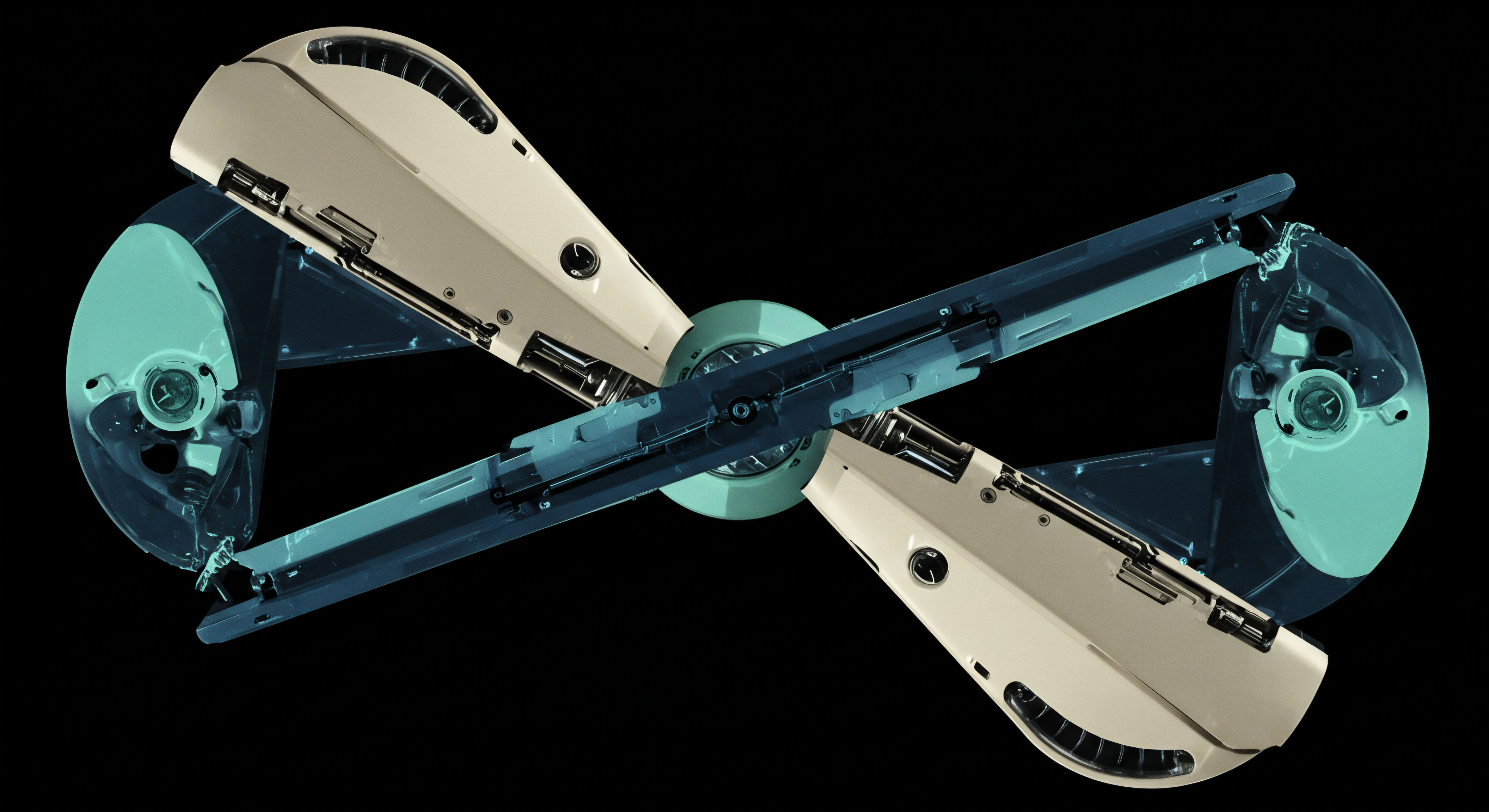

Concept

The imposition of a financial transaction tax (FTT) is frequently presented as a direct mechanism for revenue generation and for curbing speculative excess. This perspective, however, operates at the surface. The true, systemic impact of such a tax unfolds in the layers beneath the initial transaction, in the second-order effects that recalibrate the very architecture of market liquidity.

To grasp these consequences is to understand the market not as a static pool of assets, but as a dynamic system of interacting agents whose behaviors are governed by costs, incentives, and information flows. The introduction of a transaction tax acts as a fundamental change to the system’s physics, altering the cost of every interaction and thereby reshaping the strategic decisions of every participant.

At its core, market liquidity is the system’s capacity to absorb trades with minimal price impact. This capacity is provided by a diverse ecosystem of participants, from long-term institutional investors to high-frequency market makers. Each operates on different time horizons and with different cost sensitivities. A financial transaction tax is a blunt instrument applied to this delicate, heterogeneous environment.

Its primary effect is an increase in transaction costs. The second-order effects are the cascade of behavioral adaptations that this cost increase triggers. These adaptations are what truly define the new market equilibrium, and they are far more complex than a simple reduction in trading volume.

Consider the high-frequency market maker, a participant whose business model is predicated on capturing minuscule profits across millions of trades. For this agent, even a small FTT can be prohibitive, rendering their strategy unviable. The withdrawal of these participants from the market is a direct second-order effect. This withdrawal does not simply mean less trading; it means a structural change in the provision of liquidity.

The continuous, tight bid-ask spreads that these firms provide may widen, or the depth of the order book ▴ the volume of buy and sell orders at various price levels ▴ may diminish. This thinning of the market’s core liquidity layer makes it more susceptible to shocks and increases the cost for all other participants who rely on that liquidity to execute their own strategies.

Furthermore, the impact is not uniform across all assets. Less liquid securities, which already have wider spreads and lower trading volumes, are disproportionately affected. An FTT can push these assets below a critical threshold of profitability for market makers, leading to a severe contraction in liquidity or even a complete withdrawal of market-making services.

This creates a feedback loop ▴ lower liquidity leads to higher volatility, which further discourages participation, leading to even lower liquidity. The second-order effect is a fragmentation of the market, where liquid, low-cost assets remain tradable, while less liquid assets become effectively untradable for institutional size.

The behavioral response extends beyond market makers. Institutional investors, faced with higher execution costs, may alter their portfolio management strategies. They might trade less frequently, leading to a slower incorporation of new information into prices. This is the “lock-in” effect, where investors are disincentivized from rebalancing their portfolios to reflect new information or risk assessments because the cost of doing so is too high.

The consequence is a less efficient market, where prices may deviate from their fundamental values for longer periods. This degradation of price discovery is a subtle but profound second-order effect, impacting the allocative efficiency of the entire capital market.

The introduction of an FTT also creates powerful incentives for regulatory arbitrage. Market participants will actively seek ways to avoid the tax, either by shifting their trading to untaxed venues or by using derivatives and other synthetic instruments that replicate the exposure of the taxed security without triggering the tax itself. This migration of trading activity can undermine the tax’s revenue goals and create new, unforeseen risks in less regulated corners of the financial system.

The market, as a complex adaptive system, will always seek the path of least resistance. The second-order effect of an FTT is to redraw the map of that path, often in ways that regulators did not anticipate.

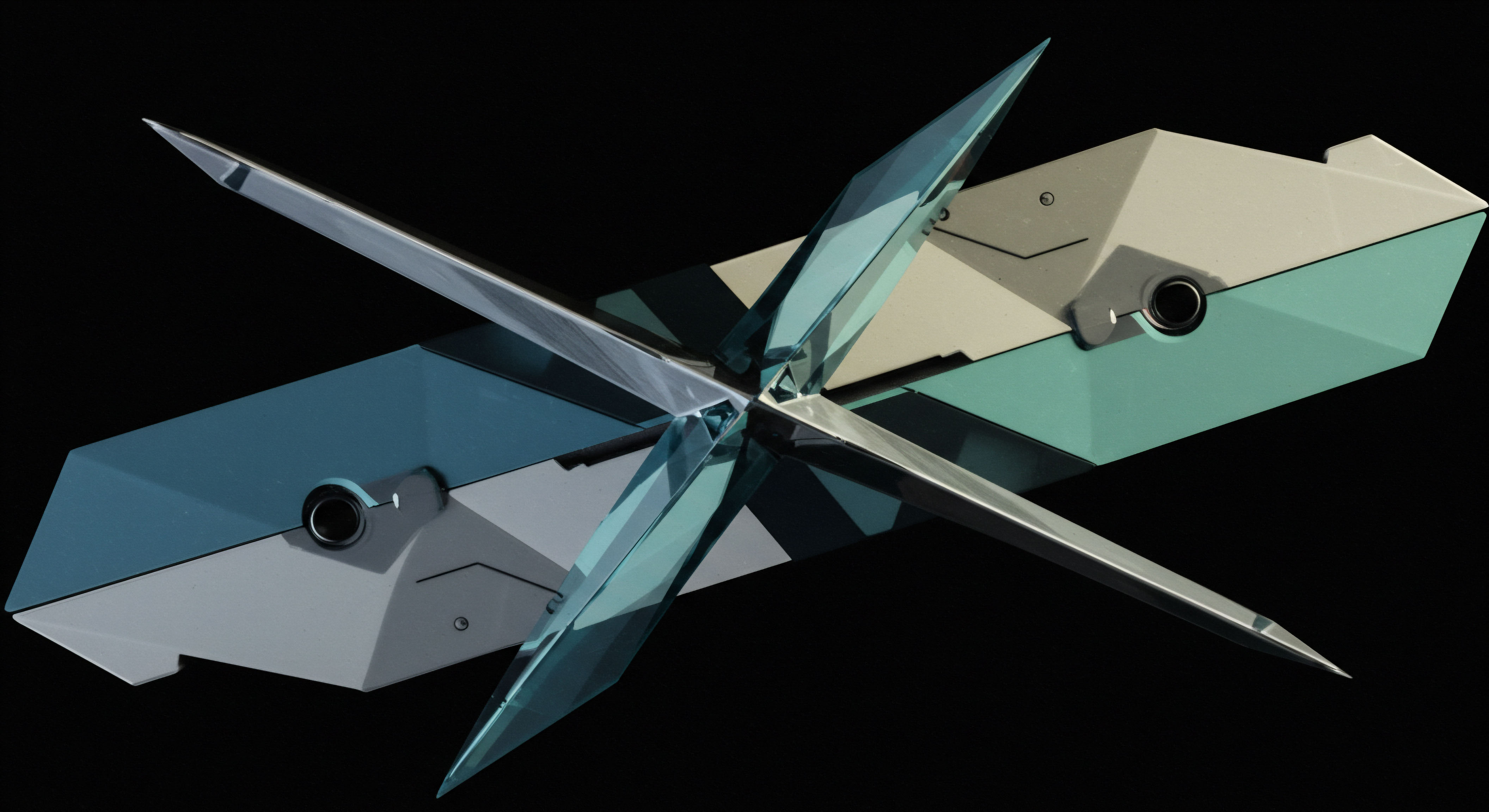

Strategy

Analyzing the strategic implications of a financial transaction tax requires moving beyond the initial, linear calculation of increased costs. A systemic view reveals a set of strategic recalibrations undertaken by market participants to navigate the altered landscape. These strategies are not uniform; they are tailored to the specific objectives and constraints of each market actor. For an institutional asset manager, the primary concern is execution quality and minimizing portfolio drag.

For a proprietary trading firm specializing in statistical arbitrage, the focus is on the viability of their high-volume, low-margin models. Understanding these divergent strategic responses is key to predicting the new market equilibrium.

A financial transaction tax fundamentally alters the strategic calculus of market participation, forcing a system-wide re-evaluation of trading, risk management, and liquidity provision.

The Strategic Response of Liquidity Providers

Liquidity providers, particularly high-frequency market makers, are at the epicenter of the FTT’s impact. Their strategies are built on the law of large numbers, executing vast quantities of trades for marginal profits. An FTT directly attacks this model by imposing a fixed cost on every transaction, which can easily exceed the razor-thin profit margins of their strategies.

The strategic response of these firms follows a clear logic:

- Strategy Abandonment ▴ For the highest-frequency strategies, where profits are measured in fractions of a basis point, the FTT may render the entire strategy unprofitable. The only rational response is to cease operations in the affected markets or securities. This is not a partial adjustment but a complete withdrawal, leading to a sudden and structural decrease in liquidity.

- Parameter Adjustment ▴ For market-making strategies with slightly wider margins, the response may be to adjust the parameters of their algorithms. This typically involves widening the bid-ask spread to incorporate the cost of the tax. The market maker is, in effect, passing the cost of the tax on to liquidity takers. The strategic goal is to maintain a target level of profitability on a per-trade basis, even if it means participating in fewer trades overall.

- Selective Deployment ▴ Market makers will also become more selective about which securities they provide liquidity for. They will concentrate their capital and algorithms on the most liquid, high-volume stocks where the impact of the FTT is relatively smaller compared to the trading volume and where spreads are already tight. Less liquid stocks, where the FTT represents a larger proportion of the bid-ask spread, will see a disproportionate reduction in market-making activity. This creates a “liquidity desert” for smaller and mid-cap stocks.

How Do Institutional Investors Adapt Their Strategies?

Institutional investors, such as pension funds and mutual funds, face a different set of challenges. Their primary objective is to implement their long-term investment views at the lowest possible cost. An FTT acts as a direct tax on their alpha-generating and risk-management activities.

- Passive Management and Index Rebalancing ▴ The rise of passive investing strategies, such as those tracking major indices like the S&P 500 or FTSE 100, is complicated by an FTT. These funds are required to rebalance their portfolios periodically to reflect changes in the index composition. An FTT increases the cost of this rebalancing, creating tracking error and reducing the returns for end investors. Strategically, fund managers may seek to rebalance less frequently or use sampling techniques to approximate the index, both of which can lead to less precise tracking.

- The “Lock-In” Effect on Active Management ▴ Active managers who rely on frequent trading to express their market views will find their strategies hampered. The cost of rotating out of one position and into another is increased, creating a “lock-in” effect. A manager might hold onto a position that they no longer have high conviction in simply because the cost of selling it and buying something new is prohibitive. This can lead to suboptimal portfolio construction and a reduced ability to react to new information.

- Migration to Alternative Execution Venues and Instruments ▴ A key strategic response for institutional investors is to seek ways to execute their trades outside the reach of the FTT. This can involve shifting trades to venues in different jurisdictions (if the tax is not applied globally) or using derivatives. For example, instead of buying a basket of stocks, an investor might buy a total return swap or an exchange-traded fund (ETF) that is not subject to the same level of taxation. This strategic migration has profound implications for market transparency and systemic risk, as it can shift activity from regulated exchanges to the less transparent over-the-counter (OTC) markets.

The Impact on Arbitrage and Price Discovery

Arbitrageurs play a crucial role in ensuring that prices remain efficient across different markets and instruments. For example, if the price of a stock deviates from the price of its corresponding futures contract, arbitrageurs will step in to buy the cheaper instrument and sell the more expensive one, pocketing the difference and, in the process, bringing the prices back into alignment. An FTT acts as a direct cost to these arbitrage strategies, creating a “band of inefficiency” within which prices can deviate without triggering a corrective arbitrage trade.

The wider this band, the less efficient the market. This degradation of price discovery means that prices are a less reliable signal of fundamental value, which can lead to a misallocation of capital across the economy.

The table below illustrates the strategic adjustments of different market participants in response to an FTT.

| Market Participant | Primary Objective | Strategic Response to FTT | Second-Order Market Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Frequency Market Maker | Profit from bid-ask spread across high volume of trades | Widen spreads; reduce or cease activity in less liquid securities; abandon highest-frequency strategies | Wider spreads for all participants; reduced market depth; increased volatility, especially in less liquid stocks |

| Institutional Asset Manager | Low-cost execution of long-term investment strategies | Trade less frequently (“lock-in”); shift to untaxed derivatives or venues; increased use of passive strategies with higher tracking error | Slower price discovery; potential for asset mispricing; shift of volume to less transparent markets |

| Statistical Arbitrageur | Exploit small, transient price discrepancies | Increase the required profit threshold for a trade; focus on more volatile assets where potential profit outweighs the tax | Wider bands of inefficiency between related securities; reduced market efficiency |

| Retail Investor | Long-term wealth accumulation | Reduced trading frequency; potential shift to buy-and-hold strategies; indirect impact through higher mutual fund/ETF fees | Reduced overall trading volume; potential for lower market participation |

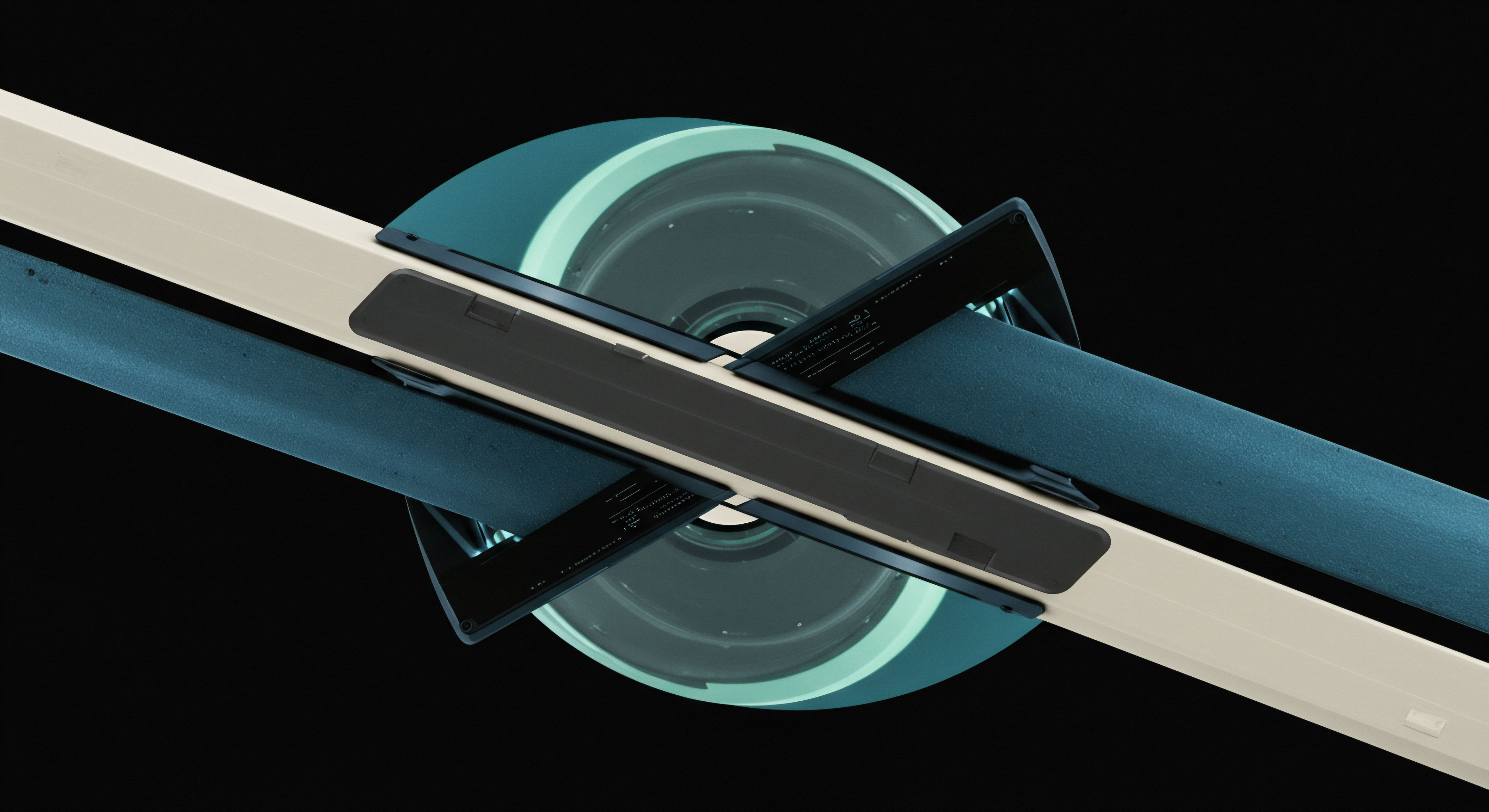

Execution

The execution of trading strategies in a market with a financial transaction tax requires a granular understanding of the new cost structure and its impact on the microstructure of liquidity. The theoretical concepts and strategic adjustments discussed previously manifest as concrete, measurable changes in the order book and in the behavior of trading algorithms. For a professional trader or an institutional execution desk, adapting to an FTT environment is an exercise in quantitative analysis and technological adaptation. The goal is to minimize the tax’s impact while achieving the desired trading outcomes.

In an FTT environment, execution excellence is achieved by dissecting the tax’s impact on market microstructure and re-engineering trading algorithms to navigate the new cost-liquidity frontier.

Quantifying the Impact on Execution Costs

The total cost of a trade, often referred to as Transaction Cost Analysis (TCA), is composed of several components. An FTT adds a new, explicit cost to this equation. The traditional TCA formula is:

Total Cost = Explicit Costs (Commissions, Fees) + Implicit Costs (Spread, Market Impact)

With an FTT, the formula becomes:

Total Cost = Explicit Costs (Commissions, Fees, FTT) + Implicit Costs (Wider Spread, Higher Market Impact)

The critical insight here is that the FTT increases both the explicit cost and the implicit cost. The tax itself is the explicit component. The second-order effects of the tax ▴ the withdrawal of liquidity providers leading to wider spreads and lower market depth ▴ increase the implicit costs. An execution desk must be able to model and predict these changes to make informed decisions about how and when to trade.

For example, a “parent” order to buy 100,000 shares of a stock might be broken down into smaller “child” orders by an execution algorithm. The algorithm’s “slicing” schedule ▴ how it decides the size and timing of the child orders ▴ is typically optimized to balance the trade-off between market impact (trading too quickly) and timing risk (trading too slowly). An FTT shifts this optimization problem. The algorithm must now consider that wider spreads and thinner depth may require a slower, more passive execution strategy to avoid excessive costs, even though this increases the risk that the price will move away from the desired level before the order is complete.

Algorithmic Adaptation to an FTT Regime

Execution algorithms must be recalibrated to function effectively in an FTT environment. This is a non-trivial engineering task that involves adjusting the core logic of how the algorithm interacts with the market.

- Passive Order Placement ▴ Algorithms will likely shift towards more passive execution strategies. This means placing more limit orders inside the spread, hoping to be “filled” by an aggressive counterparty, rather than placing market orders that cross the spread and incur its full cost. This strategy, known as liquidity provision, can sometimes earn a rebate from the exchange, which can partially offset the cost of the FTT. However, it comes with the risk that the order will not be filled if the market moves away.

- Dark Pool Aggregation ▴ Execution algorithms will be programmed to more aggressively seek liquidity in dark pools and other off-exchange venues. These venues do not display pre-trade quotes, and trades are typically executed at the midpoint of the exchange’s bid-ask spread. By executing in a dark pool, a trader can avoid paying the full spread, which becomes even more valuable when spreads have widened due to the FTT. The algorithm must be sophisticated enough to “sniff” for liquidity across multiple dark pools without revealing its intentions, a process known as “smart order routing.”

- Cross-Asset and Cross-Venue Arbitrage ▴ The FTT can create new arbitrage opportunities for sophisticated traders. If a stock is taxed but its corresponding American Depositary Receipt (ADR) traded in another country is not, an algorithm can be designed to execute the trade in the untaxed instrument. This requires a system that can monitor prices across multiple venues and asset classes in real-time and execute complex, multi-leg trades to capture the desired exposure while avoiding the tax.

What Are the Systemic Risks of FTT Avoidance Strategies?

The widespread adoption of FTT avoidance strategies, while rational for individual market participants, can introduce new systemic risks. The shift of trading volume from transparent, lit exchanges to opaque dark pools and OTC markets reduces the amount of information available to the public. This can impair the price discovery process, making it harder for all investors to gauge the true supply and demand for a security.

Furthermore, the increased use of derivatives to gain synthetic exposure can create complex and hard-to-track counterparty risk exposures. If a major dealer in the OTC derivatives market were to fail, the contagion could be far-reaching and difficult to manage.

The table below provides a simplified quantitative model of how an FTT might impact the decision to execute a trade, considering the change in the bid-ask spread.

| Parameter | Pre-FTT Scenario | Post-FTT Scenario | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Price | $100.00 | $100.00 | Assumed stable for this example. |

| Bid-Ask Spread | $0.01 (100.00 – 100.01) | $0.02 (99.99 – 100.01) | Spread widens due to withdrawal of some market makers. |

| FTT Rate (on value of transaction) | 0% | 0.10% | A hypothetical FTT rate. |

| Market Maker’s Action | Buy at bid, sell at ask | Buy at bid, sell at ask | Standard market-making round trip. |

| Gross Profit per Share | $0.01 | $0.02 | The bid-ask spread. |

| FTT Cost per Share (on both buy and sell) | $0.00 | $0.20 (0.1% of $100 on buy + 0.1% of $100.01 on sell) | Tax is applied to each leg of the trade. |

| Net Profit per Share | $0.01 | -$0.18 | The strategy becomes highly unprofitable. |

References

- Colliard, Jean-Édouard, and Peter Hoffmann. “Financial transaction taxes, market composition, and liquidity.” Journal of Finance, vol. 72, no. 6, 2017, pp. 2735-2779.

- Pomeranets, Anna, and Daniel G. Weaver. “Securities transaction taxes and market quality.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, vol. 53, no. 1, 2018, pp. 385-419.

- Umlauf, Steven R. “Transaction taxes and the behavior of the Swedish stock market.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 33, no. 2, 1993, pp. 227-240.

- Matheson, Thornton. “Taxing financial transactions ▴ Issues and evidence.” IMF Working Paper, WP/11/54, 2011.

- Capelle-Blancard, Gunther, and Olena Havrylchyk. “The impact of the French securities transaction tax on market liquidity and volatility.” European Financial Management, vol. 23, no. 1, 2017, pp. 83-107.

- Schwert, G. William, and Paul J. Seguin. “Securities transaction taxes ▴ An overview.” Journal of Financial Services Research, vol. 7, no. 2, 1993, pp. 159-173.

- Song, Wei-ling, and Jun Zhang. “Securities transaction tax and market volatility.” The Economic Journal, vol. 115, no. 506, 2005, pp. 1103-1120.

- Habermeier, Karl Friedrich, and Andrei A. Kirilenko. “Securities transaction taxes and financial markets.” IMF Working Paper, WP/03/51, 2003.

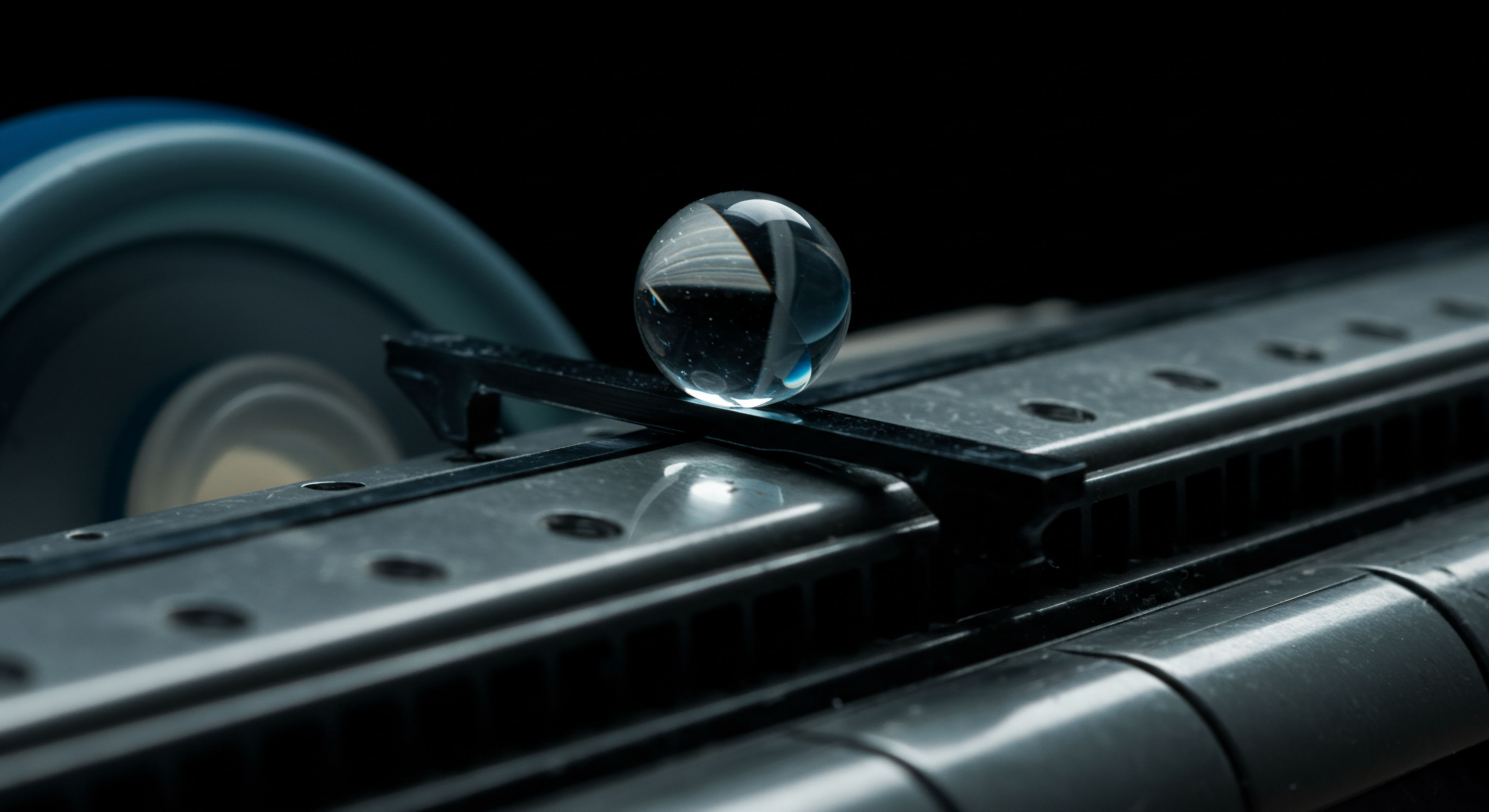

Reflection

The analysis of a financial transaction tax reveals the intricate, systemic nature of market liquidity. It demonstrates that a market is not a simple machine where one lever can be pulled with a single, predictable outcome. Instead, it is a complex adaptive system, and any intervention creates a cascade of adaptations. The knowledge of these second-order effects provides a more robust framework for evaluating such policies.

It prompts a deeper inquiry into the structure of one’s own operational framework. How resilient is your execution strategy to changes in market microstructure? How does your system monitor and adapt to shifts in liquidity patterns across different venues and asset classes? The ultimate strategic advantage lies in building a system of intelligence that can not only understand these complex dynamics but also anticipate and adapt to them in real time.

Glossary

Financial Transaction Tax

Second-Order Effects

Transaction Tax

Institutional Investors

Financial Transaction

Trading Volume

Market Makers

Price Discovery

Regulatory Arbitrage

Bid-Ask Spread

Transaction Cost Analysis

Market Impact

Market Depth

Dark Pools

Market Liquidity