Concept

The “Contract A” principle represents a fundamental legal doctrine in Canadian procurement law that re-architected the relationship between buyers and sellers in a formal bidding process. Its genesis lies in the landmark 1981 Supreme Court of Canada decision, R. v. Ron Engineering & Construction (Eastern) Ltd. which established that a specific set of conditions within a tender or Request for Proposal (RFP) process gives rise to a preliminary, binding contract ▴ termed “Contract A” ▴ the moment a compliant bid is submitted. This initial contract is distinct from the ultimate performance contract, known as “Contract B.”

Prior to this ruling, the submission of a bid was generally considered a mere offer, which the bidder could revoke at any time before the project owner accepted it. This created significant uncertainty for owners, who relied on the submitted prices to plan major projects. The Ron Engineering decision addressed this by establishing a new framework.

The issuance of the RFP document itself is construed as an offer to all potential bidders to participate in a specific, rule-based process. When a bidder submits a proposal that conforms to the RFP’s requirements, they are deemed to have accepted the owner’s offer, thereby forming “Contract A.”

The “Contract A” principle imposes a binding preliminary contract the moment a compliant bid is submitted, establishing rules of irrevocability and fairness that govern the conduct of both the bidder and the owner before any final award.

The core terms of this preliminary contract are not explicitly negotiated but are implied by the structure of the bidding process itself. These foundational terms include the irrevocability of the bid for a specified period and, crucially, a duty of fairness and good faith owed by the owner to all compliant bidders. This duty mandates that the owner must evaluate all bids based on the criteria set out in the RFP and cannot accept a non-compliant bid. The formation of “Contract A” with each compliant bidder effectively locks the parties into a procedural contract, which is then discharged for the unsuccessful bidders and matures into “Contract B” for the winner.

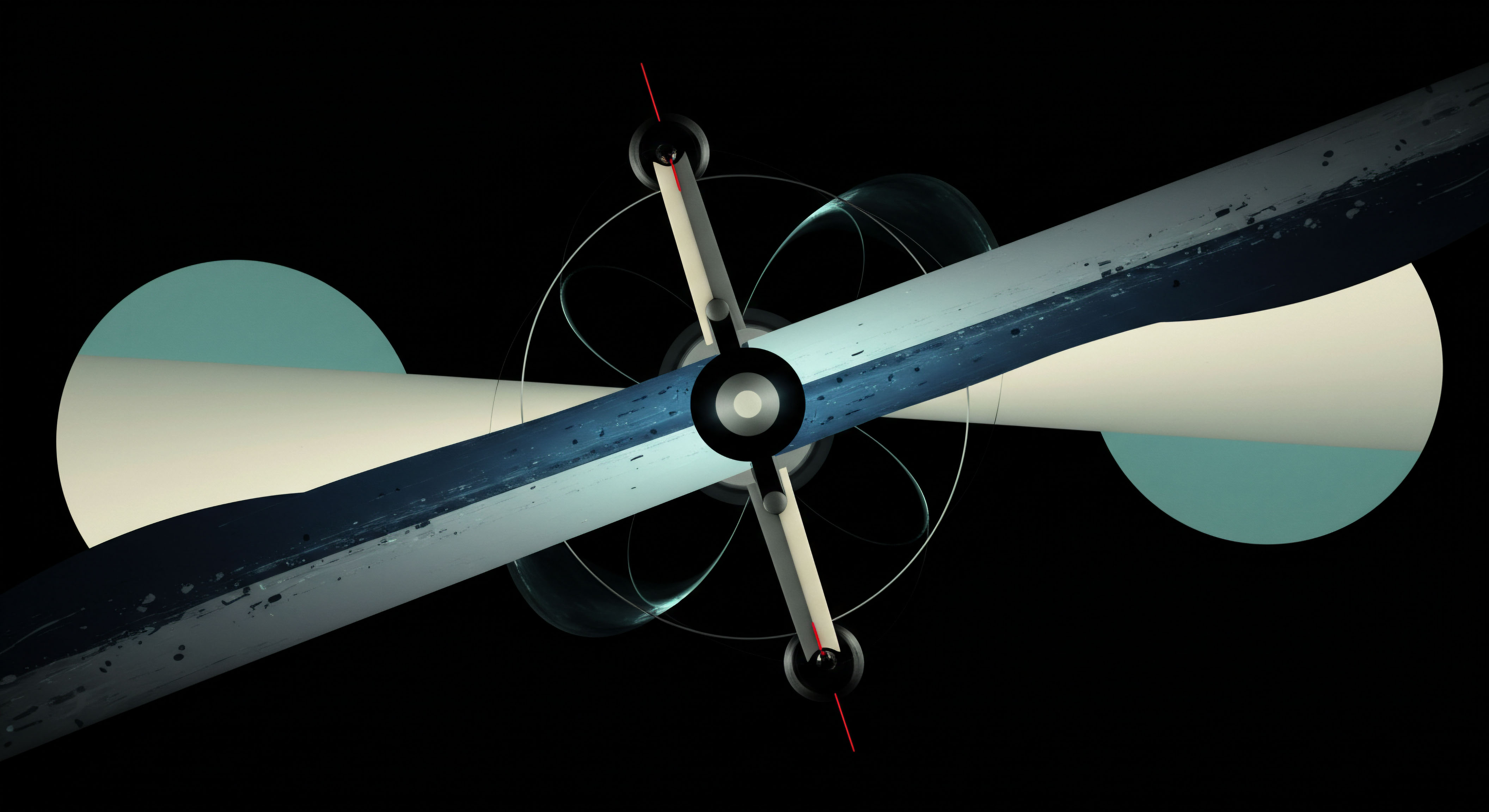

The Dual-Contract Paradigm

The “Contract A” / “Contract B” analysis creates a two-tiered contractual structure that governs the entire procurement lifecycle. Understanding this duality is essential for any entity participating in formal Canadian procurement.

Contract a the Process Contract

This initial contract governs the bidding process itself. It is a unilateral contract that springs into existence with each compliant bidder upon submission of their bid. Its primary function is to preserve the integrity of the bidding system.

- Irrevocability ▴ A central pillar of “Contract A” is that the bidder cannot withdraw their bid for the period specified in the tender documents. A bidder who attempts to do so is in breach of “Contract A” and may be liable for damages, often in the amount of the bid deposit.

- Duty of Fairness ▴ The owner is bound by an implied duty of fairness and good faith. This is a critical obligation that prevents owners from acting capriciously. It requires them to treat all compliant bidders equally, evaluate bids only on the disclosed criteria, and reject any bids that fail to meet the mandatory requirements of the RFP.

- No Undisclosed Preferences ▴ The duty of fairness prohibits the owner from applying hidden criteria or preferences during the evaluation process. The rules of the competition must be transparent and applied consistently to all participants.

Contract B the Performance Contract

This is the traditional construction or service contract that everyone aims to secure. It is the agreement to perform the actual work for the agreed-upon price.

- Formation ▴ “Contract B” is formed only when the owner formally accepts one of the compliant bids submitted under the “Contract A” framework.

- Terms and Conditions ▴ The terms of “Contract B” are typically the detailed specifications, drawings, and legal conditions outlined in the original RFP documents. The submission of the bid (“Contract A”) is an agreement to enter into “Contract B” on those terms if selected.

The establishment of this two-contract system fundamentally altered the risk landscape. For bidders, it introduced the risk of being locked into a mistaken bid. For owners, it introduced a new realm of procedural liability; a failure to adhere to the self-imposed rules of the RFP could lead to a lawsuit from a disgruntled but compliant bidder for breach of “Contract A.”

Strategy

The strategic decision to either embrace or deliberately avoid the “Contract A” framework is one of the most critical choices a procurement authority makes when designing an RFP process. This choice is a trade-off between procedural rigidity and negotiating flexibility. The optimal path depends entirely on the nature of the project, the clarity of the requirements, and the organization’s tolerance for procedural risk.

Opting for a formal “Contract A” process is a strategic commitment to integrity and price competition. This structure is most effective when the goods or services being procured are well-defined, the specifications are clear, and the primary basis for selection is price. By creating a binding process with irrevocable bids, an owner can achieve a high degree of cost certainty and demonstrate a fair, transparent, and defensible award process.

This is particularly vital in the public sector, where accountability and fairness are paramount. The rigid rules provide a shield against allegations of favoritism and ensure that all bidders are competing on a level playing field.

Choosing a procurement strategy is a deliberate act of balancing the need for the rigid integrity of “Contract A” against the desire for the adaptive flexibility of a negotiated process.

Conversely, deliberately structuring an RFP to avoid the formation of “Contract A” is a strategy geared towards flexibility and dialogue. This approach, often termed a Non-Binding RFP (NRFP), reframes the procurement process as an “invitation to treat” or a “request for negotiations.” It is the preferred model for complex projects where the requirements are not fully defined, where innovation and alternative solutions are sought, or where the owner wishes to engage in discussions with multiple proponents to refine the scope and terms of the final agreement. By explicitly disclaiming the intent to create a binding “Contract A,” the owner retains the discretion to negotiate with one or more bidders, change the scope of the project, and make a selection based on a wide range of factors without being bound by the strict procedural duties of fairness associated with the Ron Engineering framework.

Comparative Framework Analysis

The decision to use a “Contract A” RFP versus a Non-Binding RFP (NRFP) has profound implications for risk allocation, communication protocols, and the ultimate project outcome. The following table provides a comparative analysis of these two strategic approaches.

| Attribute | “Contract A” RFP (Binding Process) | Non-Binding RFP (Negotiated Process) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | An offer to enter a binding procedural contract, accepted by the submission of a compliant bid. | An invitation to negotiate; a request for information to start a dialogue. |

| Bidder’s Obligation | Bid is irrevocable for the acceptance period. Withdrawal constitutes a breach. | Proposal is typically revocable until a formal agreement (“Contract B”) is signed. |

| Owner’s Primary Duty | A strict duty of fairness to all compliant bidders. Must adhere to disclosed evaluation criteria. | A general duty to act in good faith, but with broad discretion to negotiate and select. |

| Flexibility | Low. The owner cannot deviate from the stated rules or negotiate on material terms post-bid. | High. The owner can discuss, clarify, and negotiate terms with one or more proponents. |

| Risk of Legal Challenge | High risk of procedural claims for breach of “Contract A” (e.g. accepting a non-compliant bid). | Low risk of procedural claims, but requires careful management of the negotiation process. |

| Ideal Use Case | Commoditized goods, clearly defined construction projects, public sector procurement requiring high transparency. | Complex technology solutions, innovative projects, public-private partnerships, situations with uncertain scope. |

The Role of Privilege Clauses

In an attempt to regain some of the discretion lost under the “Contract A” framework, owners frequently insert “privilege clauses” into their RFP documents. These clauses are designed to reserve certain rights for the owner. A typical privilege clause might state that the owner is not obligated to accept the lowest bid or any bid at all.

While these clauses provide a degree of flexibility, their power is not absolute. The courts have consistently ruled that a privilege clause does not override the owner’s fundamental duty to treat all bidders fairly. For instance, a clause stating “the lowest or any tender will not necessarily be accepted” allows an owner to bypass the lowest bid in favor of a higher-priced bid that offers better value according to the stated evaluation criteria. It does not, however, give the owner the right to accept a bid that is non-compliant with the mandatory requirements of the RFP.

The strategic use of privilege clauses, therefore, requires a nuanced understanding of their legal limitations. They can provide discretion within the rules of the game, but they cannot be used to change the rules after the game has begun.

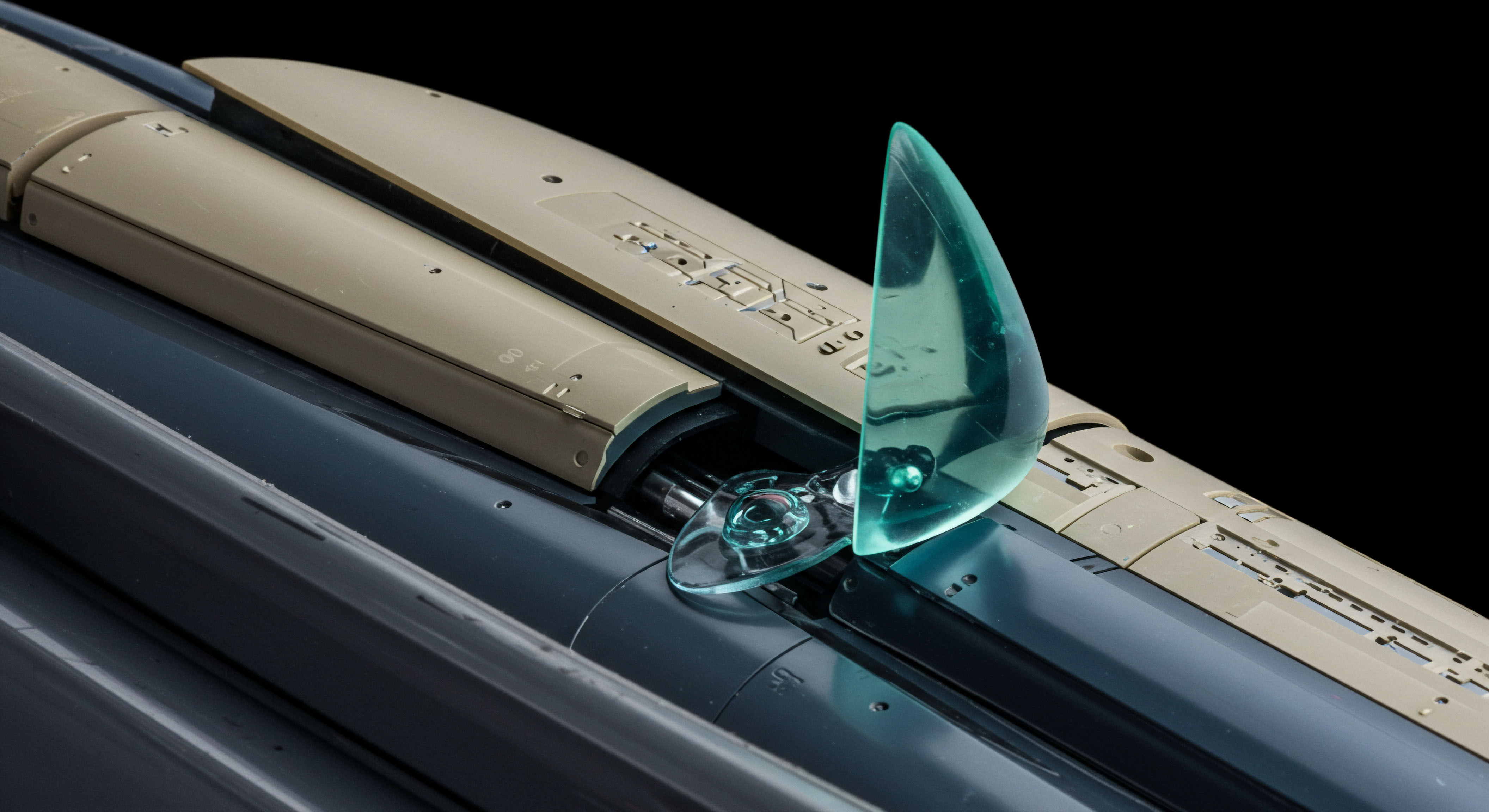

Execution

The effective execution of a procurement strategy hinges on the precise and deliberate drafting of the Request for Proposal document. The language used in the RFP is the primary determinant of whether a court will interpret the process as a binding “Contract A” framework or a non-binding invitation to negotiate. For procurement professionals, mastering the art of RFP drafting is a critical risk management skill. It involves a granular understanding of how specific clauses can create or negate legal obligations.

The core operational principle is intentionality. The procurement team must decide at the outset which framework ▴ binding or non-binding ▴ best serves the project’s goals. This decision must then be translated into clear, unambiguous language throughout the RFP. Ambiguity is the single greatest source of legal risk in this domain, as it opens the door for a court to imply obligations that the owner never intended to assume.

The Operational Playbook Drafting for Certainty

This playbook provides a procedural guide for drafting RFP documents with a clear understanding of the “Contract A” implications. The objective is to eliminate ambiguity and ensure the resulting procurement process aligns with the intended legal framework.

- Define the Desired Framework ▴ Before any drafting begins, the procurement team must formally decide and document whether the process is intended to create “Contract A” or to be a non-binding negotiation. This decision will govern all subsequent drafting choices.

-

Use an Explicit Statement of Intent ▴ The most effective tool for avoiding “Contract A” is a clear, prominently placed clause that explicitly disclaims any intent to create a binding process. Conversely, if a “Contract A” is intended, the document should refer to itself as a formal “Invitation to Tender.”

- To Avoid “Contract A” ▴ Include a clause such as ▴ “This Request for Proposals is an invitation to treat and is not a call for tenders. No contractual relationship or “Contract A” shall arise between the Owner and any Proponent upon the submission of a proposal. The Owner reserves the right to negotiate with any or all Proponents, or none at all.”

- To Create “Contract A” ▴ Use formal tender language, specify that bids are irrevocable, and clearly state that a compliant bid will be evaluated according to the stated criteria.

-

Control the Terms of “Contract B” ▴ The level of detail regarding the final performance contract is a key indicator of intent.

- To Avoid “Contract A” ▴ Avoid attaching a final, non-negotiable version of “Contract B.” State that the final contract will be subject to negotiation based on the successful proposal.

- To Create “Contract A” ▴ Attach the complete and final form of “Contract B” to the RFP, indicating that the successful bidder will be expected to sign it without material changes.

-

Manage Bid Submission Requirements ▴ The requirements for bid submission also signal the nature of the process.

- To Avoid “Contract A” ▴ Avoid mandatory, forfeitable bid security. While you can still require information on financial stability, a formal bid bond is a strong indicator of a “Contract A” process.

- To Create “Contract A” ▴ Require a bid deposit or bid bond that is forfeitable if the bidder withdraws their bid or refuses to enter into “Contract B.”

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

A quantitative approach can help organizations assess the risks embedded in their RFP templates. The following tables provide models for scoring RFP clauses and for estimating potential damages in the event of a breach.

Contract a Risk Scoring Matrix

This matrix assigns a risk score to common RFP clauses. A higher cumulative score for an RFP document indicates a greater likelihood that a court would find an implied “Contract A.”

| RFP Clause Type | Example Language | “Contract A” Risk Score (1-10) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclaimer of Contract | “This RFP is not a tender and shall not give rise to a ‘Contract A’.” | 1 | Explicitly negates the formation of “Contract A.” This is the strongest risk mitigation tool. |

| Privilege Clause | “The lowest or any proposal will not necessarily be accepted.” | 5 | Acknowledges a formal process but reserves discretion. Does not, by itself, prevent “Contract A” from forming. |

| Mandatory Bid Security | “All bids must be accompanied by a 10% bid bond.” | 9 | A requirement for a forfeitable security deposit is a hallmark of the Ron Engineering framework. |

| Fixed Irrevocable Period | “Bids shall remain irrevocable for a period of 90 days.” | 8 | A core term of “Contract A.” Imposes a binding obligation on the bidder. |

| Attached Form of “Contract B” | “The successful proponent will be required to execute the attached form of agreement.” | 9 | Indicates that all material terms are set and there is nothing left to negotiate, which is characteristic of a formal tender. |

| Right to Negotiate | “The Owner reserves the right to negotiate the final terms with the preferred proponent.” | 2 | Strongly suggests an “invitation to treat” rather than a formal offer. Incompatible with the rigid “Contract A” structure. |

Predictive Scenario Analysis

Case Study ▴ The Axiom Corp Data Center RFP

Axiom Corp, a growing technology firm, issued an RFP for the construction of a new data center. The procurement team, aiming for some flexibility, drafted an RFP that was a hybrid of binding and non-binding language. The RFP included a detailed set of specifications and a clause stating that “proposals shall be irrevocable for 60 days.” However, it also included a privilege clause stating, “Axiom Corp reserves the right to reject any or all proposals and to negotiate with the proponent whose proposal is deemed to be in the best interest of the company.” The RFP did not attach a final form of the construction contract.

Three companies submitted bids ▴ BuildIt Inc. ($10 million), ConnectAll Ltd. ($10.5 million), and a late, non-compliant bid from DataStructures Co. ($9.8 million). BuildIt Inc.’s bid was fully compliant.

ConnectAll Ltd.’s bid was also compliant and included an innovative, value-added cooling solution that was not explicitly asked for in the RFP but was highly attractive. Axiom’s evaluation team was impressed by ConnectAll’s innovation and, citing the “best interest” language in their privilege clause, entered into exclusive negotiations with them. They ultimately awarded the “Contract B” to ConnectAll for a slightly modified scope at a price of $10.4 million. They rejected BuildIt Inc.’s bid, stating only that it was not selected.

A flawed procurement process can result in an organization paying for a project twice once to the chosen contractor and again in damages to a wronged bidder.

BuildIt Inc. filed a lawsuit, claiming Axiom had breached “Contract A.” Their argument was that the combination of detailed specifications and an irrevocability period created a formal tender process, binding Axiom to a duty of fairness. They argued that by negotiating exclusively with ConnectAll and being influenced by an “undisclosed preference” for an innovative cooling system, Axiom had breached its duty to evaluate all bids solely on the stated criteria. Furthermore, they argued that even considering the late bid from DataStructures Co. was a procedural flaw.

In a hypothetical court ruling, a judge would likely find in favor of BuildIt Inc. The judge would reason that the irrevocability clause was a strong indicator of a “Contract A” process, despite the conflicting “right to negotiate” language. The ambiguity would be construed against Axiom, the drafter of the document.

The court would find that Axiom breached its duty of fairness by ▴ (1) considering a non-compliant late bid, and (2) applying an undisclosed evaluation criterion (the innovative cooling system) that gave ConnectAll an unfair advantage. The court would award damages to BuildIt Inc. for their lost profits on the project, calculated as their bid price minus their estimated costs, plus their bid preparation costs.

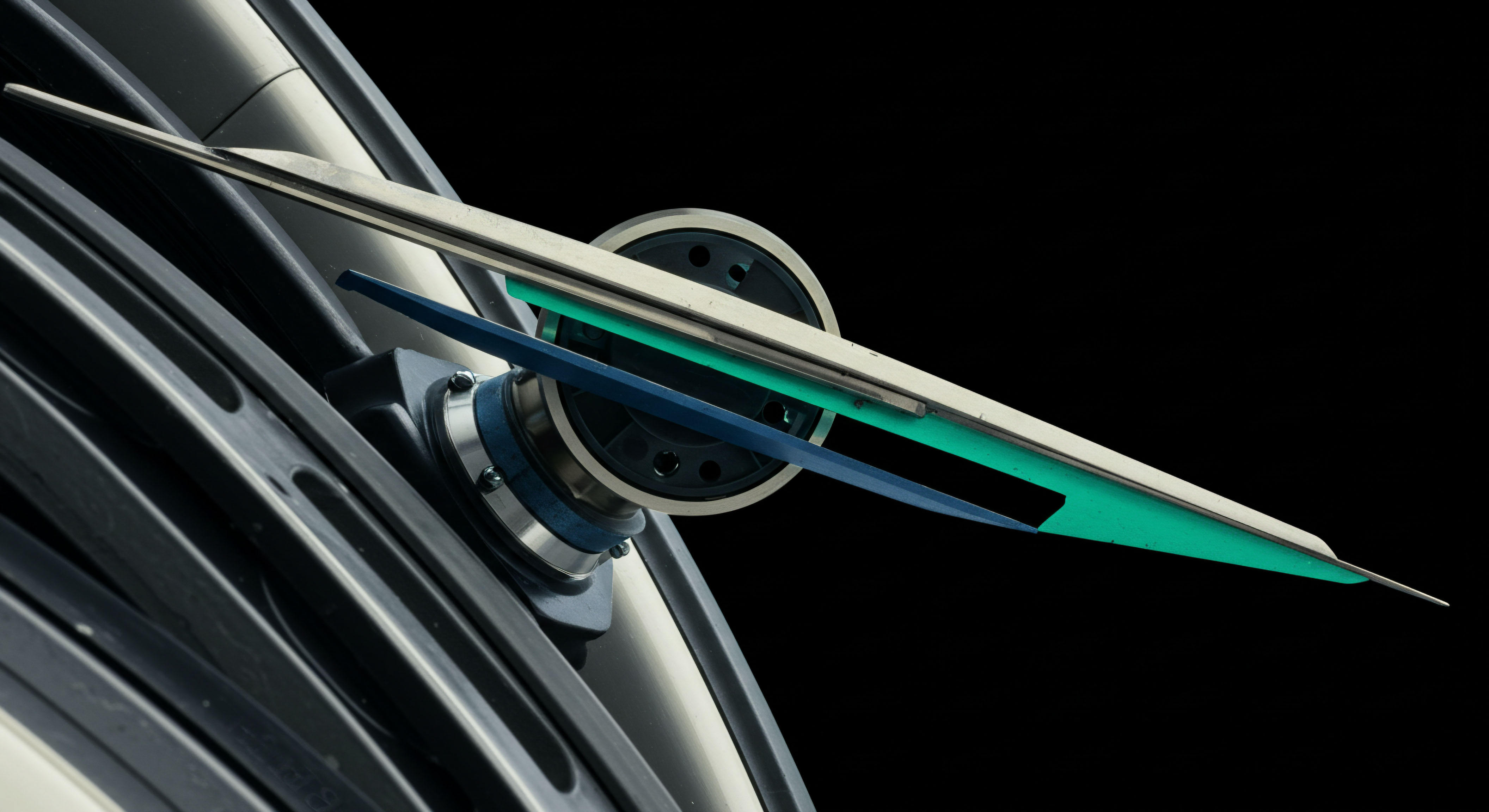

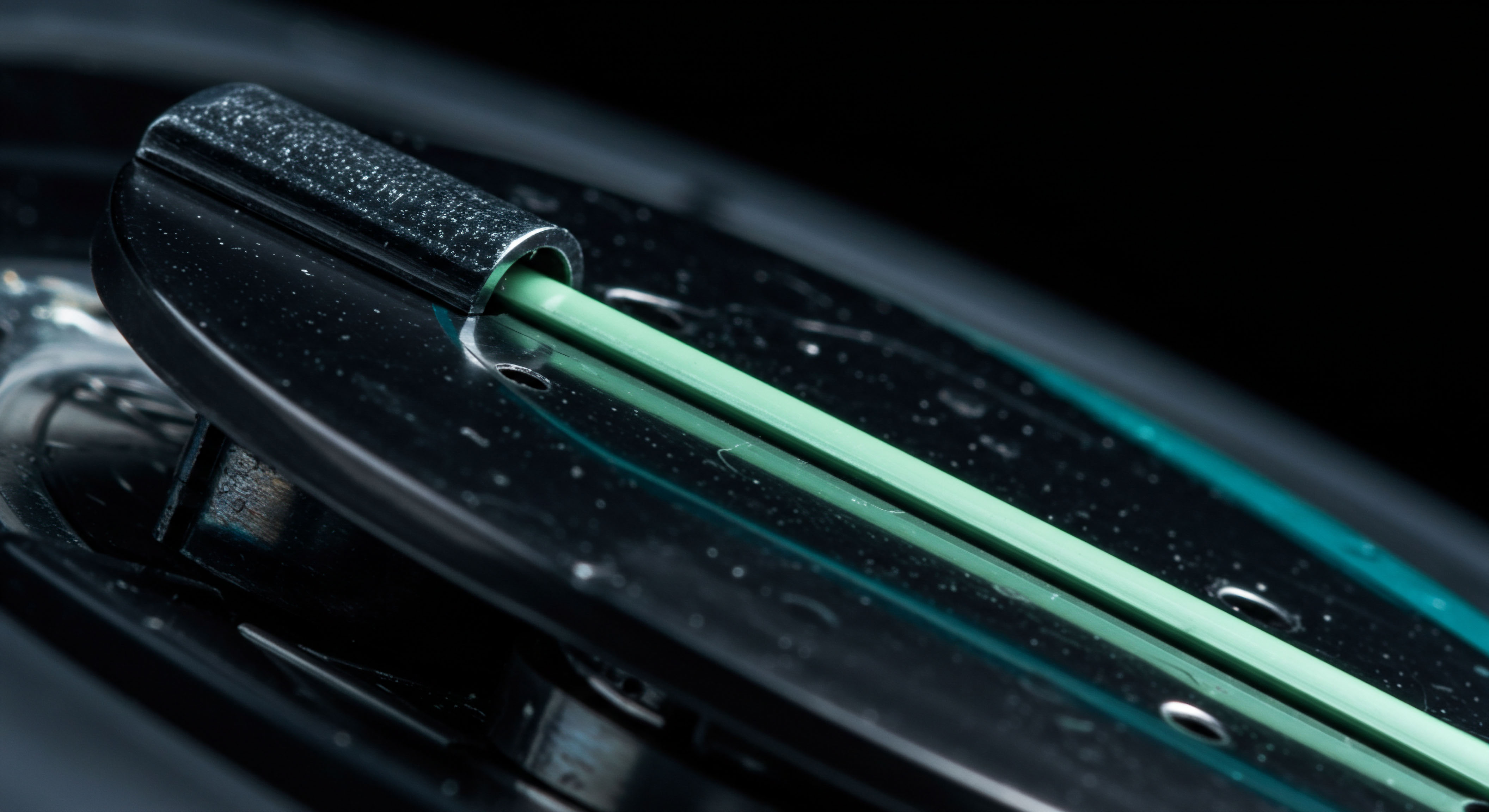

System Integration and Technological Architecture

Modern e-procurement platforms can be architected to manage the complexities of the “Contract A” principle. These systems provide a technological framework for ensuring compliance and mitigating risk.

- Clause Library Module ▴ A central repository of pre-approved, legally vetted RFP clauses. Procurement officers can select from a menu of clauses that are clearly categorized as either “Contract A Creating” or “Non-Binding.” This prevents the accidental use of ambiguous or high-risk language by standardizing the drafting process.

- Compliance Matrix Generator ▴ An automated tool that parses a draft RFP and cross-references its clauses against a risk database. The system can flag potentially conflicting clauses (e.g. an irrevocability clause paired with a right-to-negotiate clause) and generate a “Contract A Risk Score,” as modeled above, providing a quantitative risk assessment before the RFP is issued.

- Secure Bidding Portal ▴ A system that enforces the rules of the procurement process. It can be configured to automatically reject bids submitted after the deadline, ensure the confidentiality of bids until the official opening, and create an immutable audit trail of all submissions and communications, providing a robust defense against claims of procedural unfairness.

References

- Marston, D. L. (1996). Law for Professional Engineers. McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

- Goldsmith, I. & Heintzman, T. G. (2022). Goldsmith on Canadian Building Contracts. Carswell.

- Ricchetti, L. & Murphy, T. (2011). The 2011 Annotated Ontario Building Code Act. Carswell.

- Sandori, P. & Pigott, W. M. (2015). Bidding and Tendering ▴ What Is the Law? (5th ed.). LexisNexis Canada.

- Supreme Court of Canada. (1981). R. v. Ron Engineering & Construction (Eastern) Ltd. 1 S.C.R. 111.

- Revay, S. G. (1996). The Ron Engineering Decision ▴ Fifteen Years Old and Still Immature. Revay Report.

- Pattison, R. (2004). Overview of the Law of Bidding and Tendering. The Canadian Bar Review, 83(3), 757-780.

- Stiver, L. (2013). The Legal Implications of Issuing an RFP. Win Without Pitching.

- Thurston, C. (2023). Tender, RFP, RFQ ▴ When does “Contract A arise?”. Ontario Construction News.

- Alexander Holburn Beaudin + Lang LLP. (2016). Legal basics of procurement – Part 2 (Duty of good faith).

Reflection

The principles emanating from the Ron Engineering case compel a level of intentionality in procurement that transcends mere process. The decision to employ a binding or non-binding framework is a foundational act of system design, with cascading consequences for risk, fairness, and flexibility. Understanding the “Contract A” doctrine moves a procurement professional from being a manager of transactions to an architect of competitive systems.

The true measure of success is not simply the execution of a single procurement, but the construction of a robust, defensible, and intelligent framework that consistently delivers value while safeguarding the integrity of the process. The knowledge gained here is a component in that larger operational intelligence, a tool for building a decisive and sustainable strategic advantage.

Glossary

Procurement Law

Ron Engineering

Contract A

Duty of Fairness

Compliant Bid

Contract B

Good Faith

Rfp Process

Invitation to Treat

Procurement Process

Non-Binding Rfp

Privilege Clauses