Concept

The Objective Arbiter in Commercial Agreements

In the architecture of contract law, the reasonableness standard functions as a foundational protocol designed to ensure systemic stability and predictability. It is the objective arbiter, a silent third party to every agreement that lacks explicit, quantifiable metrics for performance. When parties enter into a contract, they are building a system of mutual obligations.

However, language is an imperfect tool for construction; gaps, ambiguities, and unforeseen circumstances are inevitable system vulnerabilities. The reasonableness standard operates to patch these vulnerabilities, not by consulting the private, subjective intentions of the parties, but by referencing an external, objective benchmark ▴ the hypothetical “reasonable person.” This is a construct representing a composite of ordinary prudence, commercial awareness, and contextual understanding, ensuring that the contract’s operational integrity is maintained even when its literal terms are silent or unclear.

This standard’s primary role is to fill the lacunae that inevitably appear in the contractual framework. As modern English law evolved to govern complex business dealings, the invocation of what is “reasonable” became a pervasive mechanism to make agreements workable in practice. It prevents a contract from failing due to uncertainty and provides a court with the tools to enforce the agreement’s underlying commercial purpose. For instance, if a contract for the sale of goods fails to specify a delivery date, the law does not render the contract void.

Instead, the reasonableness standard is activated, implying a term that delivery must occur within a “reasonable time.” Determining this timeframe involves a systemic analysis of all relevant variables ▴ the nature of the goods, industry norms, the purpose of the contract, and any communications between the parties. The standard thus acts as a dynamic, context-aware algorithm that calculates an appropriate performance metric where the parties themselves failed to specify one.

A reasonableness standard is an objective measure, assessing a party’s actions against what a sensible person with similar knowledge and in a similar situation would have done.

The implementation of this standard is rooted in the objective theory of contracts, which prioritizes the external manifestations of intent over internal, unexpressed thoughts. As established in landmark cases, if a party conducts themselves in a way that a reasonable person would believe they are assenting to the proposed terms, they are bound by that conduct, regardless of their actual, private intention. This principle is fundamental to commercial reliability. It allows participants in a market to trust the apparent meaning of actions and words, creating a stable environment for transactions.

The reasonableness standard is the primary tool for evaluating this external conduct. It asks not what the specific individual party thought was fair, but what a composed, rational, and informed participant in that specific context would deem appropriate. This objective viewpoint is what distinguishes reasonableness from the more subjective standard of “good faith,” which often looks to the party’s actual state of mind.

Ultimately, the reasonableness standard is a mechanism for risk allocation and dispute resolution. It sets a baseline for conduct and performance that, while flexible, is not arbitrary. It signals to contracting parties that their actions and decisions, particularly where they are granted discretion, may be scrutinized through an impartial lens.

This encourages clearer drafting and more conscientious performance, as parties understand that their conduct must be justifiable to an external observer. It is a core component of the legal system’s effort to balance contractual freedom with the need for fairness and commercial efficacy, ensuring that the intricate machinery of commerce operates smoothly and equitably.

Strategy

Navigating Contractual Obligations through an Objective Lens

Strategically engaging with the reasonableness standard requires a shift in perspective, from viewing a contract as a static document to understanding it as a dynamic system governed by objective principles. For legal practitioners and commercial managers, this means proactively analyzing and shaping contractual obligations through the lens of a hypothetical third-party observer. The standard is not merely a fallback for resolving disputes; it is a strategic tool that can be leveraged during negotiation, drafting, and performance to manage risk and reinforce one’s commercial position. A key strategic decision involves the deliberate choice between a “reasonableness” standard and a “good faith” standard for governing a counterparty’s discretionary actions.

A reasonableness standard imposes an objective test, asking what a rational market participant would do, whereas a good faith standard is subjective, inquiring into the party’s actual state of mind ▴ whether they honestly believed they were acting appropriately. For the party on the receiving end of a discretionary decision, insisting on a “reasonableness” qualifier is almost always the superior strategic choice. It provides a more robust, evidence-based foundation for challenging a decision that appears commercially unsound, as one can point to industry benchmarks and objective data. Conversely, a party seeking maximum flexibility in its own discretionary powers might advocate for a “good faith” standard, though courts often end up applying an objective reasonableness test anyway when subjective intent is difficult to prove.

Comparative Analysis of Discretionary Standards

Understanding the strategic implications of different standards of conduct is essential for effective contract drafting and negotiation. The choice of standard directly impacts the allocation of risk and the potential avenues for dispute resolution.

| Standard | Basis of Evaluation | Strategic Advantage for Non-Discretionary Party | Strategic Advantage for Discretionary Party | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasonableness | Objective (The “Reasonable Person”) | Provides a strong, evidence-based ground for challenging adverse decisions. Aligns with market norms and commercial logic. | Encourages justifiable, defensible actions, reducing litigation risk if decisions are sound. | Determining timelines, quality of services, exercising powers like termination for cause. |

| Good Faith | Subjective (“Honesty in fact”) | Protects against outright dishonesty or malicious intent. | Provides wider latitude for action, as long as it is not dishonest. Harder for the other party to challenge successfully. | Obligations to negotiate, situations requiring broad discretion where an objective standard is impractical. |

| Sole Discretion | Subjective (The Party’s Own Judgment) | Minimal protection; only a challenge based on the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is possible. | Maximum flexibility and control over the decision-making process. | Highly sensitive commercial decisions, such as consent to assignment or approval of key personnel. |

Drafting and Performance Strategies

The strategic application of the reasonableness standard extends directly to the drafting process. Instead of leaving terms like “reasonable efforts” or “commercially reasonable endeavors” as vague placeholders, strategic drafting involves building a contextual framework around them. This can be achieved through several techniques:

- Defining the Parameters ▴ Where possible, drafters can specify what “reasonableness” entails in the context of a particular clause. For example, a “commercially reasonable efforts” clause could be supplemented with a non-exhaustive list of required actions, such as a minimum marketing spend, a commitment to assign a certain number of personnel, or adherence to specific industry protocols.

- Establishing Objective Benchmarks ▴ Incorporating external standards or metrics can anchor the concept of reasonableness to concrete data. A clause requiring a price to be “commercially reasonable” can be tied to a specific market index or the average of quotes from three independent suppliers. This transforms a potentially ambiguous term into a calculable one.

- Documenting the Process ▴ During the performance phase, a party’s actions are its primary evidence of reasonableness. A crucial strategy is to maintain a clear, contemporaneous record of the decision-making process. If a party must make a “reasonable” choice, documenting the factors considered, the alternatives evaluated, and the rationale for the final decision creates a powerful evidentiary shield against future challenges. This demonstrates a diligent and considered approach that aligns with what a reasonable person would do.

The core strategy is to control the narrative of reasonableness by defining its boundaries within the contract and substantiating performance with objective evidence.

This proactive approach transforms the reasonableness standard from a source of legal uncertainty into a manageable element of contract risk. By anticipating how a neutral arbiter would view their actions, parties can guide their conduct and shape the contractual language to align with their commercial objectives, thereby minimizing the potential for costly disputes and ensuring the agreement operates as a reliable system for achieving business goals.

Execution

Systematizing Reasonableness in Contractual Frameworks

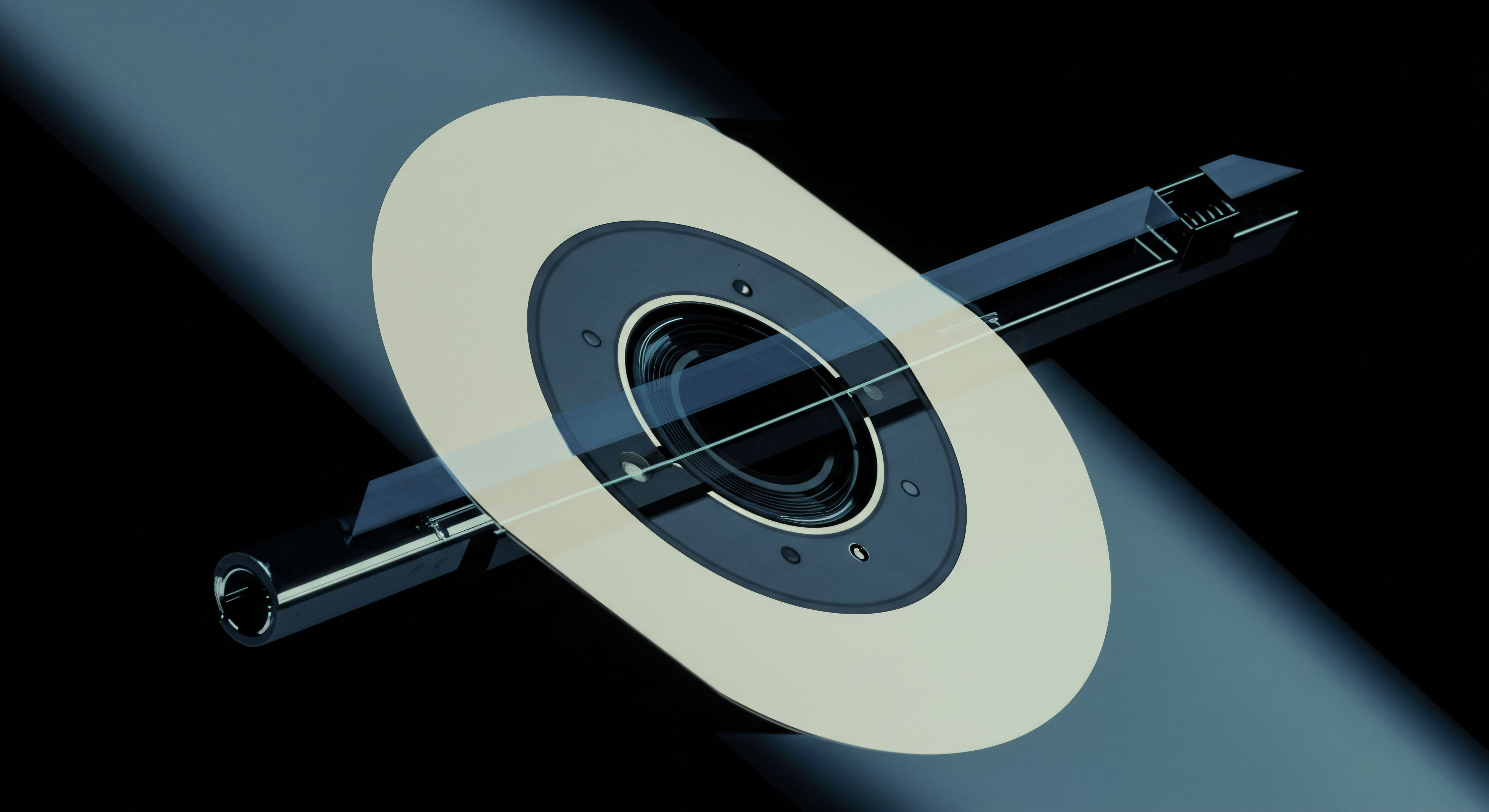

Executing on the concept of reasonableness requires moving beyond theoretical understanding into a structured, operational discipline. For an organization, this means embedding the principles of objective assessment into the entire contract lifecycle, from initial drafting to performance management and dispute resolution. This operationalization is not about eliminating ambiguity ▴ an impossible task ▴ but about managing it with systemic rigor. It involves creating internal protocols, analytical models, and technological systems designed to produce and document conduct that aligns with the legal standard of reasonableness, thereby building a robust and defensible contractual posture.

The Operational Playbook

An effective operational playbook for managing reasonableness risk is a procedural guide that standardizes how an organization approaches ambiguous contractual obligations. It provides a clear, step-by-step methodology for employees, ensuring that decisions made under a reasonableness standard are consistent, justifiable, and well-documented.

- Clause Analysis and Risk Tiering ▴

- Identification ▴ The first step is to systematically scan all new and existing contracts to identify clauses that invoke a reasonableness standard, either explicitly (“reasonable efforts,” “reasonable notice”) or implicitly (gaps in specified timelines or quality metrics).

- Categorization ▴ Each identified clause should be categorized by its function (e.g. performance obligation, discretionary power, condition precedent).

- Risk Tiering ▴ Assign a risk level (High, Medium, Low) to each clause based on its potential financial and operational impact. A “commercially reasonable efforts” clause tied to a core revenue-generating activity is a High-Risk clause. A “reasonable time” for acknowledging a non-critical notice is Low-Risk.

- Pre-Execution Strategy Formulation ▴

- Define the “Reasonable” Actor ▴ For each High-Risk clause, create a profile of the “reasonable person” in that specific context. What industry knowledge would they possess? What are the prevailing commercial norms? This profile serves as the benchmark for all subsequent actions.

- Establish Action Protocols ▴ Develop a specific, pre-defined set of actions that will be considered the baseline for “reasonable efforts.” For a software development contract, this might include assigning a minimum number of senior developers, conducting weekly progress reviews, and using a specific bug-tracking system.

- Set Documentation Standards ▴ Mandate the type and frequency of documentation required to evidence performance. This includes meeting minutes, decision logs, correspondence, and records of resources expended. The goal is to create a contemporaneous audit trail.

- Performance-Phase Monitoring and Documentation ▴

- Active Tracking ▴ Implement a system (ideally within a Contract Lifecycle Management platform) to actively monitor performance against the established action protocols for all High-Risk clauses.

- Decision Logging ▴ For any discretionary decision made under a reasonableness standard, the responsible manager must complete a “Decision Rationale Form.” This form should detail the options considered, the objective criteria used for evaluation (e.g. cost, time, quality), and the explicit reason for the chosen course of action.

- Periodic Review ▴ The legal or contract management team should conduct periodic reviews of the documentation being generated for High-Risk clauses to ensure compliance with the playbook.

- Dispute Resolution Preparation ▴

- Assemble the Evidentiary Package ▴ In the event of a dispute, the playbook allows for the rapid assembly of a comprehensive evidentiary package. This package will contain the risk analysis, the action protocols, and the detailed logs of performance and decision-making.

- Construct the Narrative ▴ Use the evidentiary package to construct a clear narrative demonstrating how the organization’s conduct consistently met or exceeded the standard of a reasonable actor in that commercial context. This shifts the argument from a subjective debate about fairness to an objective presentation of documented facts.

Quantitative Modeling and Data Analysis

While legal reasonableness is a qualitative concept, its associated risks can be modeled quantitatively to inform strategic decisions. By translating qualitative risks into quantitative metrics, an organization can better prioritize resources, price contracts, and make informed choices about litigation.

Table ▴ Reasonableness Risk Score (RRS) Model

This model provides a framework for scoring the risk associated with clauses that rely on a reasonableness standard. The RRS is calculated for each clause to guide resource allocation for risk mitigation.

| Risk Factor | Description | Weight | Score (1-5) | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Impact (FI) | The potential direct financial loss or gain tied to the clause’s outcome. | 40% | 5 | 2.0 |

| Operational Criticality (OC) | The degree to which the clause’s performance impacts core business operations. | 30% | 4 | 1.2 |

| Subjectivity Level (SL) | The degree of inherent ambiguity in the clause’s language (e.g. “reasonable” is more subjective than “commercially reasonable in the automotive industry”). | 20% | 5 | 1.0 |

| Precedent Scarcity (PS) | The lack of clear legal precedent or established industry norms for the specific obligation. | 10% | 3 | 0.3 |

| Total RRS | Formula ▴ (FI 0.4) + (OC 0.3) + (SL 0.2) + (PS 0.1) | 100% | N/A | 4.5 |

An RRS above 4.0 would classify a clause as High-Risk, triggering the full suite of protocols from the Operational Playbook. This data-driven approach ensures that mitigation efforts are focused where they are most needed.

Predictive Scenario Analysis

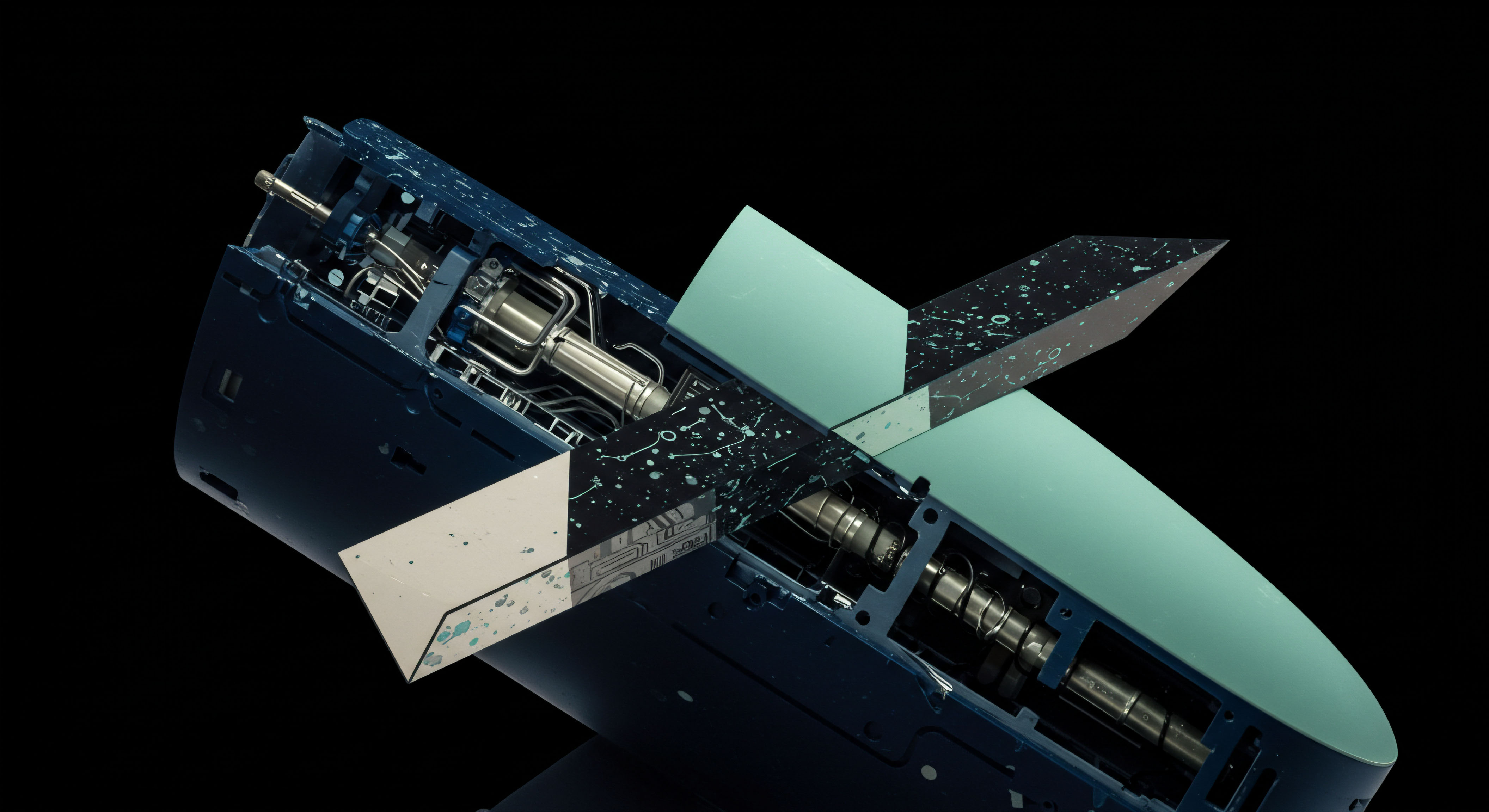

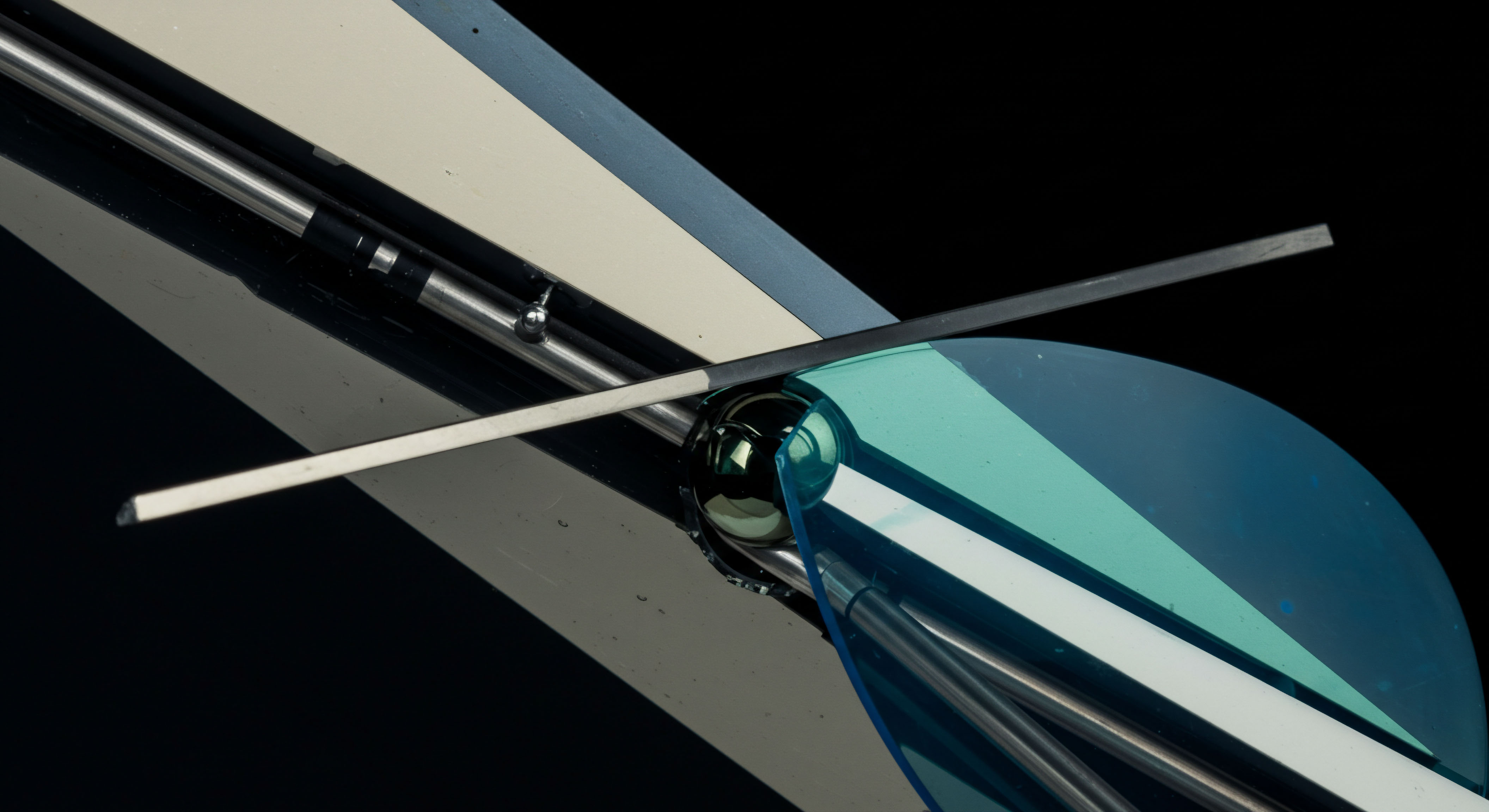

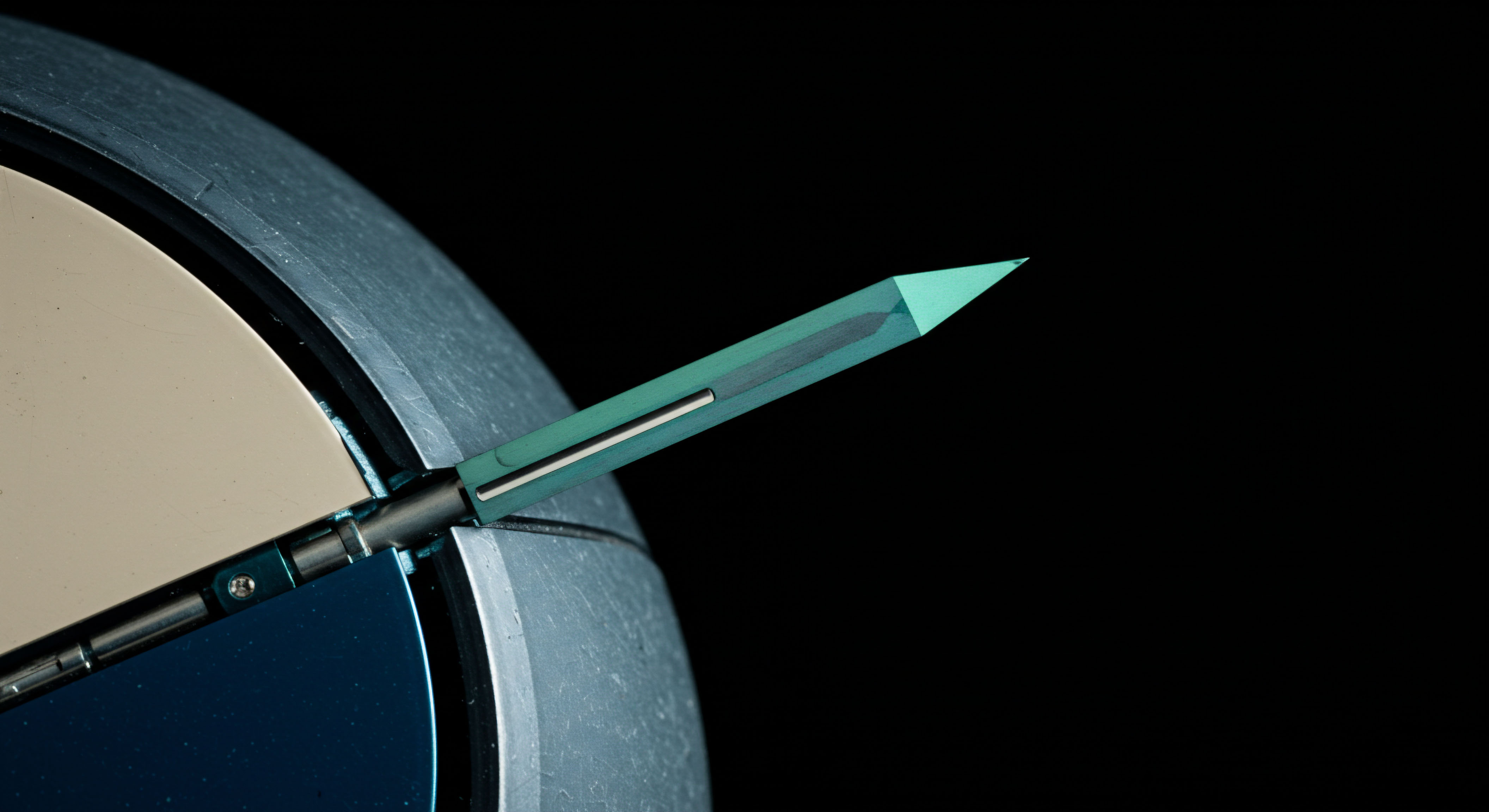

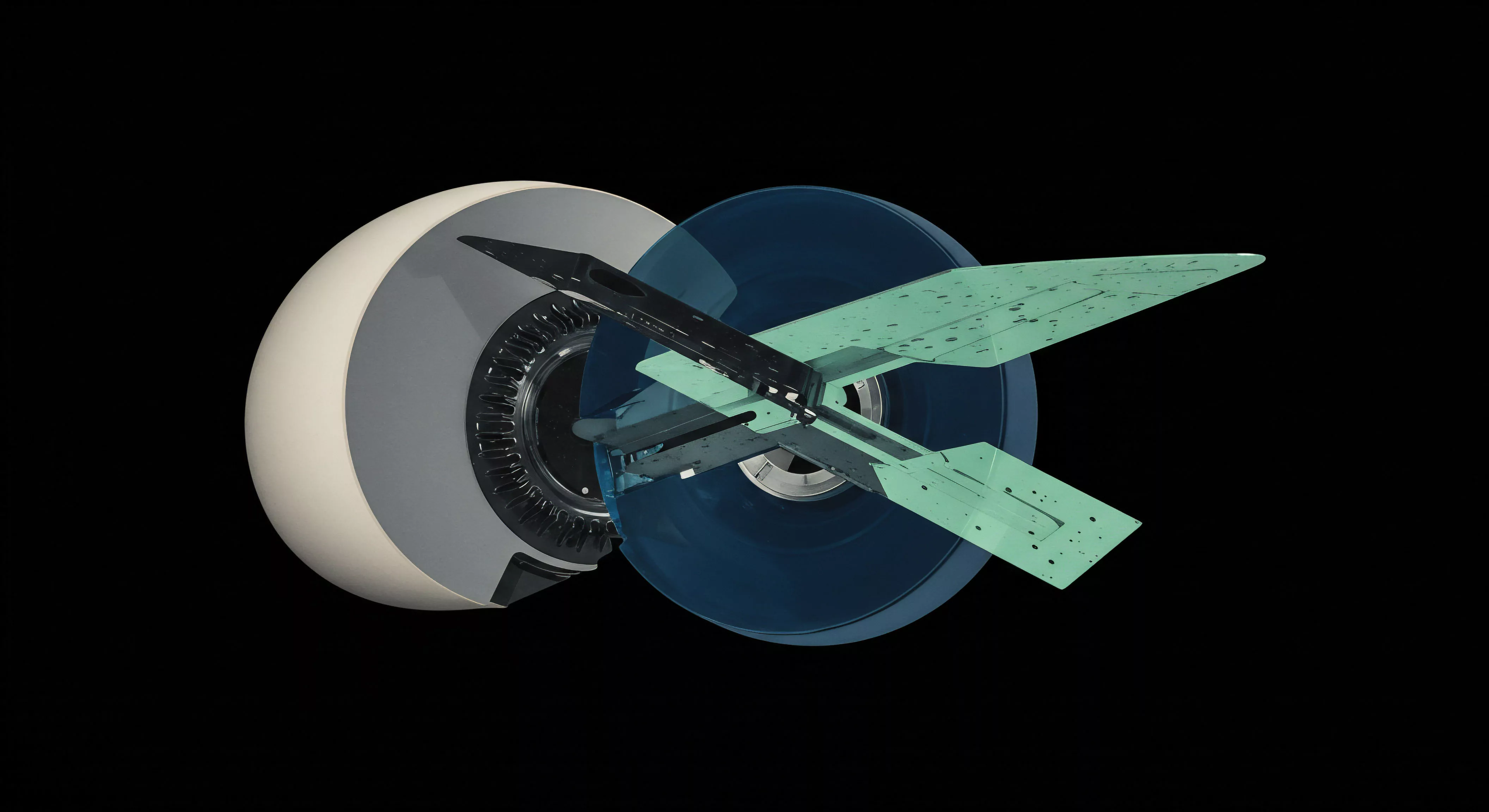

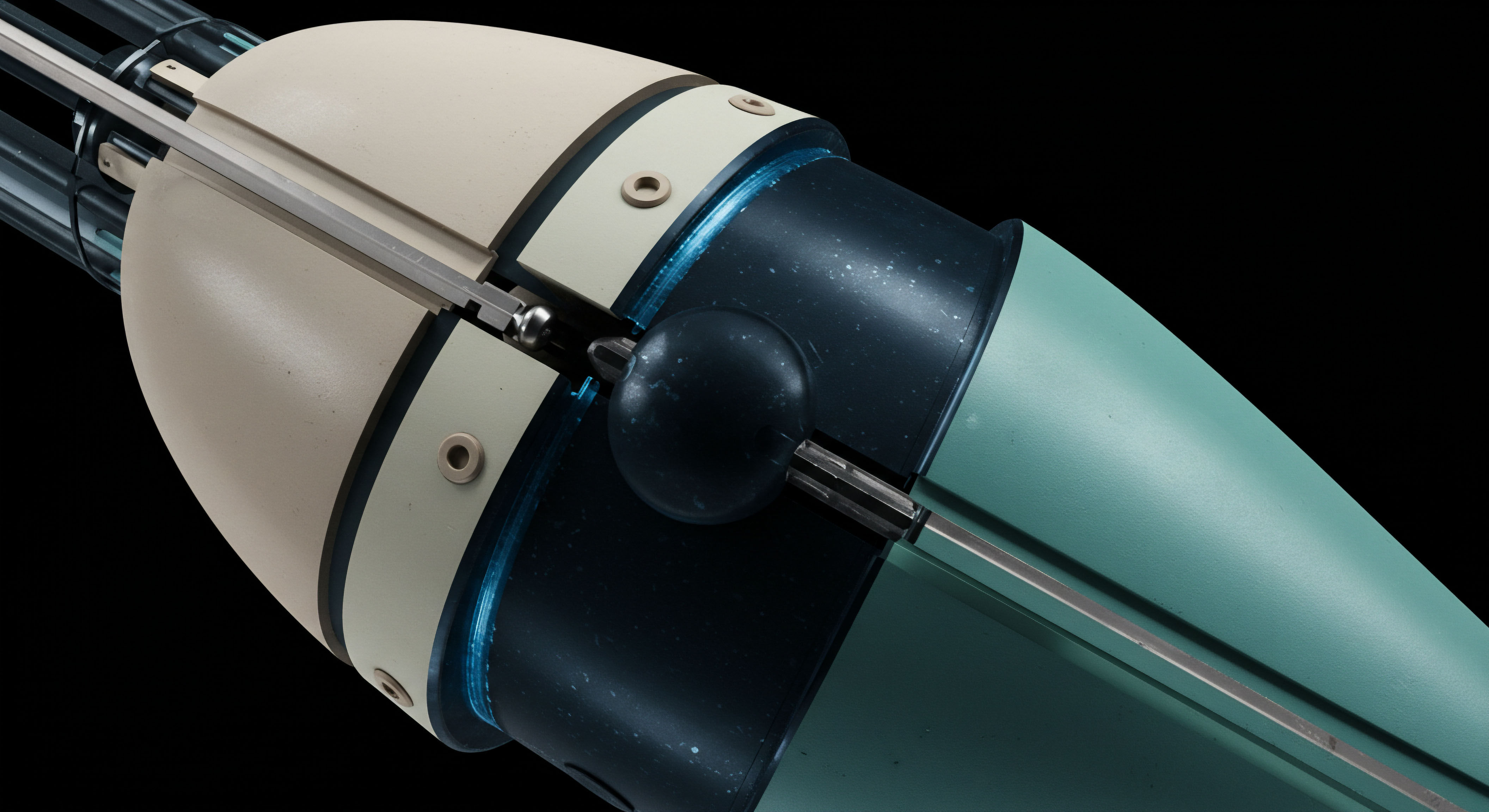

Consider the case of “AeroForge Inc. ” a manufacturer of specialized aerospace components, and “QuantumLeap,” a startup developing a new satellite constellation. They sign a supply agreement where AeroForge commits to using “commercially reasonable efforts” to develop and deliver a novel alloy component by a target date, Q4 2026.

The contract price is $50 million, with a $10 million bonus for on-time delivery. The term “commercially reasonable efforts” is left undefined.

Initially, development proceeds smoothly. AeroForge assigns a standard project team and follows its typical R&D process. Six months in, a key raw material supplier unexpectedly declares bankruptcy, disrupting the global supply chain. The price of the material from alternative suppliers triples.

Simultaneously, a senior engineer on the QuantumLeap project at AeroForge leaves the company. AeroForge’s management, facing cost pressures from other projects, decides against paying the premium for the raw material and replaces the senior engineer with a more junior one to save on salary costs. They log these decisions internally as “prudent cost-management.” Progress slows, and they miss the Q4 2026 deadline.

QuantumLeap, having missed its satellite launch window, sues AeroForge for breach of contract, claiming damages far exceeding the contract value due to lost first-mover advantage. They argue AeroForge failed to use “commercially reasonable efforts.” AeroForge counters that it acted reasonably given the unforeseen circumstances of the supply chain disruption and personnel change. They present their internal logs as evidence of prudent management.

A court’s analysis, guided by the reasonableness standard, would likely dissect AeroForge’s decisions through an objective, commercial lens. QuantumLeap’s legal team would present expert testimony establishing the industry norm for high-stakes aerospace R&D. This testimony would suggest that a “reasonable” actor in AeroForge’s position, facing a critical supply disruption for a $50 million contract with a $10 million bonus, would have paid the premium for the raw material. The cost, while significant, would be weighed against the immense value and strategic importance of the contract. The decision to absorb the higher cost would be framed as a standard commercial risk in the aerospace sector.

Furthermore, the replacement of a senior engineer with a junior one would be heavily scrutinized. QuantumLeap would argue that a reasonable manufacturer would have actively recruited another senior specialist or reassigned one from a less critical project to ensure the timeline for this high-value contract was met. AeroForge’s internal justification of “cost-management” would be viewed not through the lens of their overall corporate profitability, but through the lens of their specific obligation to QuantumLeap. The court would likely find that these decisions, while perhaps beneficial to AeroForge’s short-term bottom line, were not commercially reasonable in the context of fulfilling their contractual promise to QuantumLeap.

The predictive outcome is a probable finding against AeroForge. The court would conclude that “commercially reasonable efforts” required prioritizing the success of the contract over ordinary cost-saving measures, especially given the high stakes. The damages could be substantial, as the court would consider the foreseeable consequences of the delay for QuantumLeap’s business.

This scenario illustrates that executing under a reasonableness standard requires a dedicated, project-specific focus that may sometimes conflict with broader, internal corporate financial objectives. It is a stark reminder that the standard is external and objective, not internal and subjective.

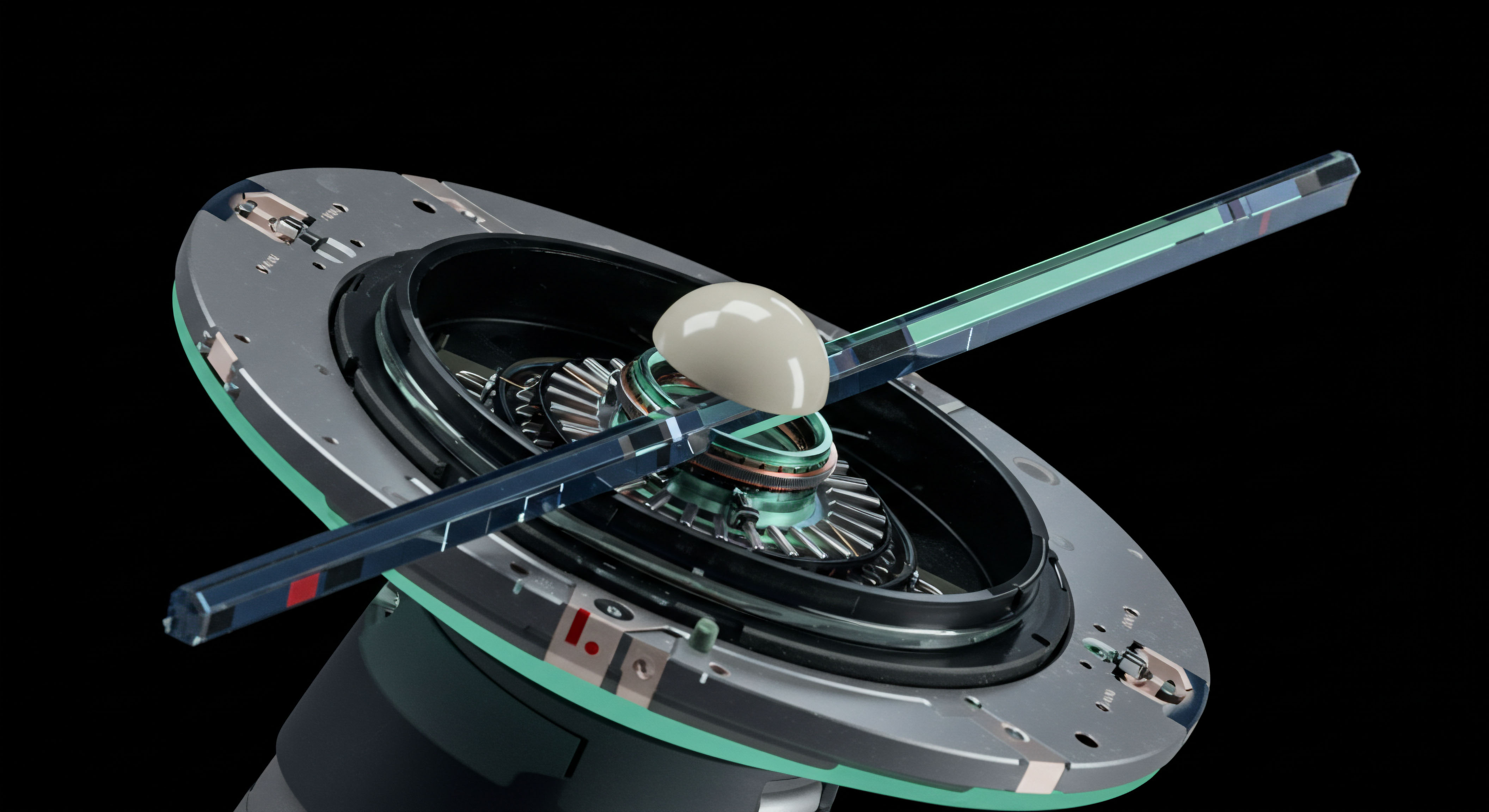

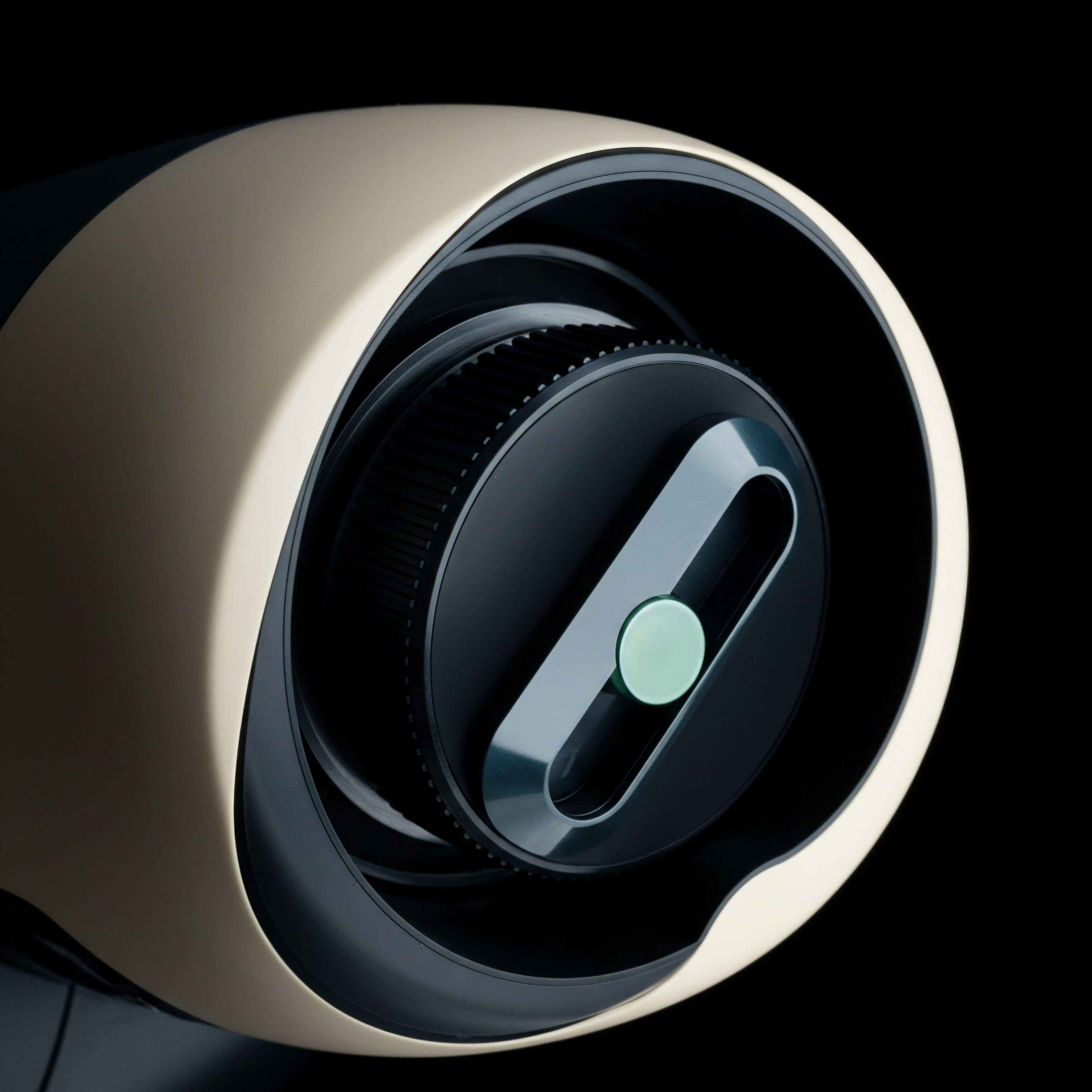

System Integration and Technological Architecture

Modern execution of the reasonableness standard is deeply intertwined with technology, specifically Contract Lifecycle Management (CLM) systems. An advanced CLM platform can be architected to serve as the central nervous system for operationalizing reasonableness.

- AI-Powered Clause Analysis ▴ The system’s architecture should include a natural language processing (NLP) engine trained to automatically detect and flag clauses containing reasonableness language during contract ingestion. This engine can perform the initial risk tiering based on pre-defined parameters, alerting the legal team to high-risk obligations.

- Integrated Obligation Management ▴ Once a high-risk clause is identified, the CLM should automatically create a set of linked tasks and assign them to the relevant business owners. For a “reasonable efforts” clause, this could trigger tasks for project management to upload resource allocation plans, for finance to approve necessary expenditures, and for legal to review progress reports.

- Centralized Documentation Repository ▴ The system must provide a secure, auditable, and centralized repository for all documentation related to performance. This is the technological execution of the “contemporaneous record.” Every email, report, and decision log associated with a specific obligation is linked directly to that clause in the contract database. This ensures that the evidentiary package is always complete and accessible.

- Dynamic Data Integration ▴ For clauses requiring “commercially reasonable” pricing or terms, the CLM architecture can include APIs that integrate with external market data feeds (e.g. commodity price indices, currency exchange rates). This allows the system to provide real-time, objective data to business owners, helping them make and document decisions that are demonstrably reasonable in the context of the current market. This transforms a subjective assessment into a data-supported conclusion.

By integrating these technological components, an organization creates a robust system that not only ensures compliance with the operational playbook but also generates a powerful, defensible record of its conduct. This systemic approach to execution transforms the abstract legal concept of reasonableness into a manageable, measurable, and strategically advantageous component of contract management.

References

- Cole, T. R. H. (1994). The concept of reasonableness in construction contracts. Building and Construction Law Journal, 10(1), 7-17.

- Adams, K. (2021). Reasonableness and Good Faith in Contracts. Adams on Contract Drafting.

- Frisch, D. (2015). Reasonable Standards for Contract Interpretations under the CISG. California Western International Law Journal, 46(1), 1-28.

- Pasternak, M. (2022). The ‘good’ and the ‘reasonable’ in contract law. Journal of Law and Society, 49(2).

- Calnan, A. (2020). The Nature of Reasonableness. Cornell Law Review, 105(2), 1435-1482.

- Miller, A. D. & Perry, R. (2012). The Reasonable Person. New York University Law Review, 87(2), 323-392.

- Benson, P. (2020). The Idea of a Public Basis of Justification for Contract Law. In G. Klass, G. Letsas, & P. Saprai (Eds.), Philosophical Foundations of Contract Law (pp. 91-116). Oxford University Press.

- Hillas & Co Ltd v Arcos Ltd UKHL 2.

- Smith v Hughes (1871) LR 6 QB 597.

- United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), Apr. 11, 1980, S. Treaty Doc. No. 98-9 (1983), 1489 U.N.T.S. 3.

Reflection

The Unseen Partner in Every Agreement

The exploration of the reasonableness standard reveals its fundamental role as the unseen partner in every commercial agreement. It is a dynamic force that shapes obligations, guides conduct, and ultimately ensures the functional integrity of a contract. Understanding this standard is not an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for building resilient and effective commercial systems. The knowledge gained here should prompt an inward examination of your own organization’s operational framework.

How are ambiguous obligations currently managed? Is the process for documenting discretionary decisions robust and systematic? Is technology being leveraged to transform abstract legal risks into manageable, data-informed tasks?

Mastering the interplay with this objective arbiter is about more than just legal compliance. It represents a higher level of operational control and strategic foresight. By embedding the principles of objective reasonableness into your organization’s DNA ▴ its protocols, its technology, its decision-making culture ▴ you are not merely mitigating risk. You are architecting more predictable, more defensible, and ultimately more valuable commercial relationships.

The true potential lies in viewing every contract not as a static set of terms, but as a dynamic system that must be actively and intelligently managed. The reasonableness standard is simply one of the most critical operating rules within that system.

Glossary

Reasonableness Standard

Contract Law

Reasonable Person

Good Faith

Dispute Resolution

Discretionary Powers

Commercially Reasonable

Reasonable Efforts

Commercially Reasonable Efforts

Operational Playbook

Contract Lifecycle Management

Evidentiary Package