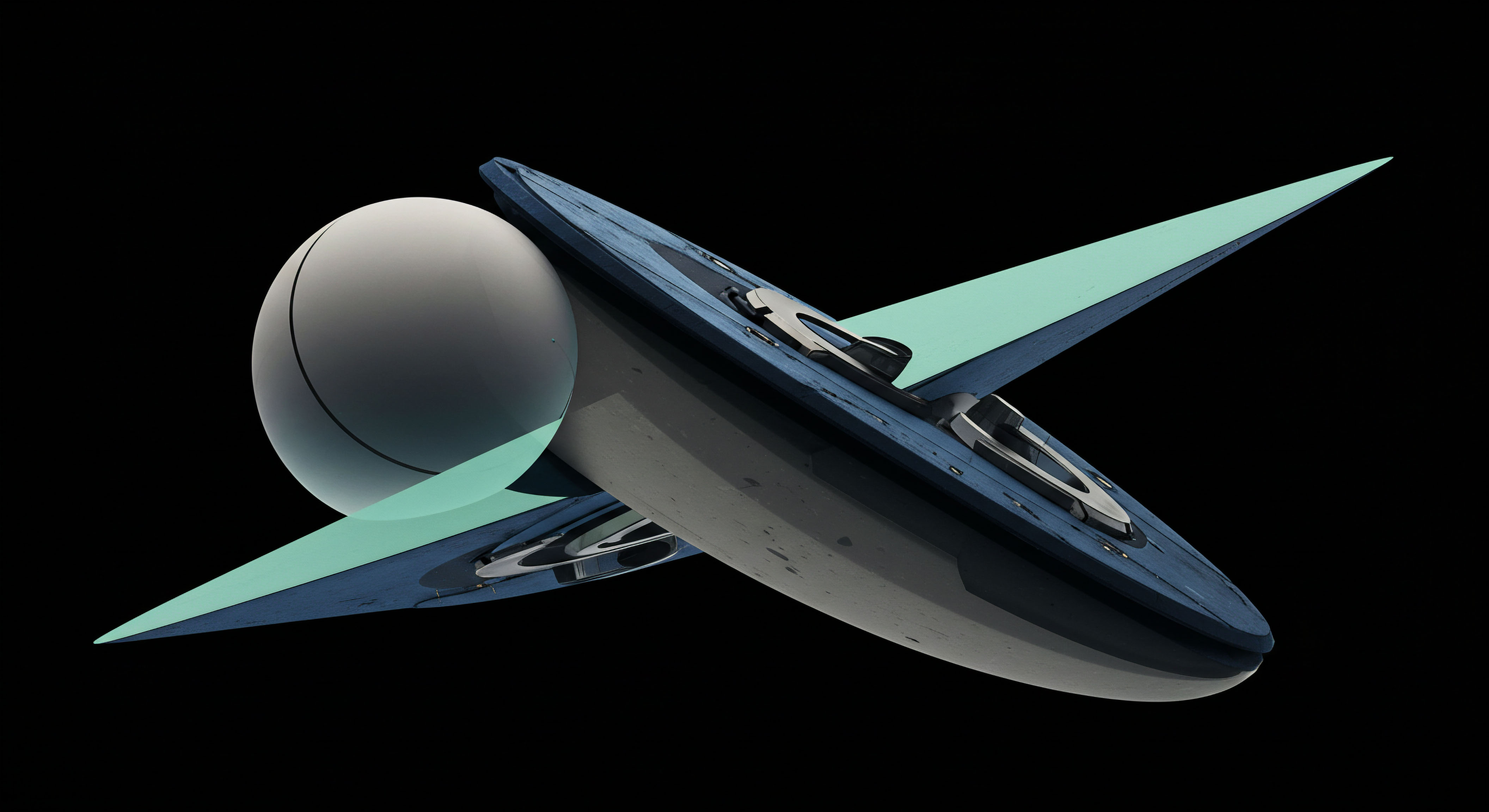

Concept

To comprehend the legal challenges inherent in the enforcement of the first method of antitrust regulation is to understand the foundational shift in the relationship between state power and private enterprise. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was not merely a piece of legislation; it was the establishment of a new economic constitution for the United States. Its core challenge stemmed from its profound linguistic simplicity. The Act’s prohibitions against “every contract, combination. or conspiracy, in restraint of trade” and against any person who shall “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize” were revolutionary in their breadth and, consequently, in their ambiguity.

The initial and most enduring legal obstacle was the act of translation ▴ converting these broad, almost philosophical prohibitions into a concrete, predictable, and enforceable body of law. This was a task left almost entirely to the judiciary, which for decades wrestled with the fundamental question of what constituted an “unreasonable” restraint of trade versus a natural consequence of vigorous competition. The first method’s enforcement was therefore an exercise in creating a new legal language, one capable of distinguishing between predatory behavior and the legitimate pursuit of market dominance that is the very engine of a capitalist economy.

The Sherman Act’s primary legal challenge was translating its broad, ambiguous prohibitions into a concrete and enforceable body of law capable of distinguishing between anticompetitive behavior and legitimate market competition.

The early legal battles were not just about the actions of specific trusts like Standard Oil, but about the very soul of American commerce. Courts were tasked with drawing lines where none had existed before. For instance, how could a court differentiate between a large company achieving a monopoly through superior products and business acumen, which the law did not forbid, and one that achieved it through “willful acquisition or maintenance” of that power through exclusionary tactics? This distinction, while clear in theory, is extraordinarily difficult to prove in practice.

The evidence required to demonstrate intent to monopolize, as opposed to simply an intent to succeed, became a central legal battlefield. The first method’s enforcement was thus a continuous process of judicial interpretation, a slow, case-by-case construction of a framework for competitive conduct that had to be both flexible enough to adapt to a rapidly industrializing economy and rigid enough to provide clear guidance to businesses. The legal challenges were, in essence, the challenges of defining the rules of a game that was already being played at a ferocious pace.

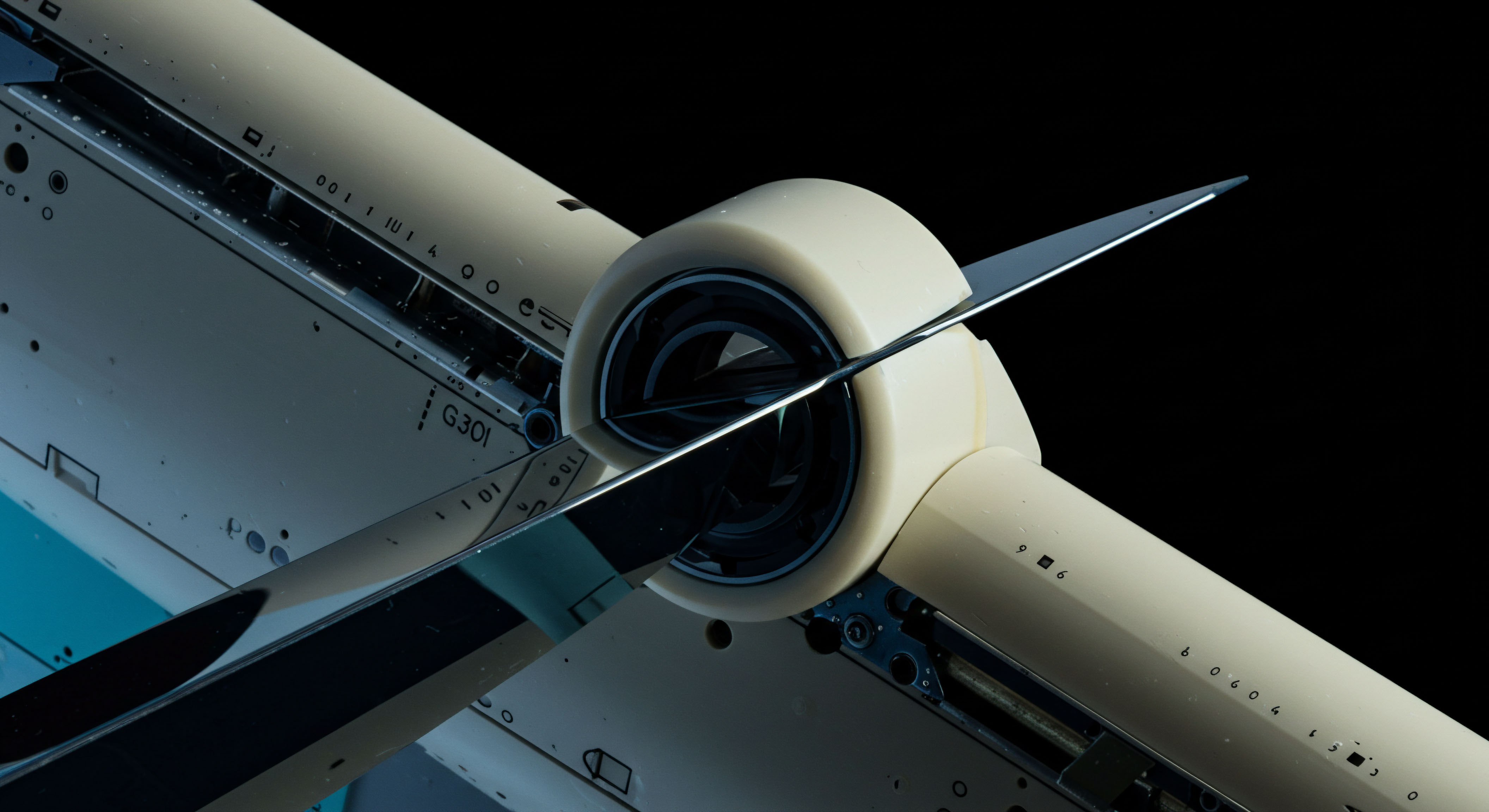

Strategy

The strategic enforcement of the Sherman Act has been characterized by a long and complex evolution, driven by shifting economic philosophies and judicial interpretations. The initial strategy was one of discovery, with the Department of Justice and the courts attempting to give meaning to the Act’s broad language. This led to the development of two critical, and often conflicting, strategic approaches ▴ the “rule of reason” and the concept of “per se” violations. The “rule of reason,” articulated in the landmark 1911 Supreme Court decision against Standard Oil, held that only “unreasonable” restraints of trade were illegal.

This approach required a deep, fact-intensive analysis of a company’s conduct and its effect on the market, making enforcement a costly and uncertain endeavor. In contrast, the “per se” rule emerged for conduct deemed so inherently anticompetitive that it was illegal on its face, without any need to prove actual harm to competition. This category includes practices like price-fixing, bid-rigging, and market allocation. The strategic challenge for enforcers has always been to decide which framework to apply and to convince the courts of their choice.

The Shifting Sands of Enforcement Philosophy

For much of the 20th century, antitrust strategy was heavily influenced by the “structuralist” school of thought, which held that concentrated market structures were inherently conducive to anticompetitive behavior. This led to a more aggressive enforcement posture, particularly against mergers, even those involving relatively small market shares. However, beginning in the 1970s, the Chicago School of economics began to exert a profound influence on antitrust strategy. Proponents of this school argued that the market was largely self-correcting and that many business practices previously condemned as anticompetitive were, in fact, efficient and beneficial to consumers.

This led to a strategic shift toward a more lenient enforcement standard, with a greater emphasis on demonstrating concrete harm to consumer welfare. The “rule of reason” became the dominant mode of analysis, and the bar for proving monopolization was raised significantly. This strategic pivot created new challenges for enforcers, who now had to meet a higher evidentiary burden and contend with more sophisticated economic defenses from accused firms.

The strategic evolution of antitrust enforcement has been a tug-of-war between the fact-intensive “rule of reason” and the more rigid “per se” illegality, with the prevailing philosophy often dictated by the dominant school of economic thought.

The table below illustrates the strategic shift in antitrust enforcement, contrasting the structuralist era with the Chicago School era.

| Strategic Element | Structuralist Era (c. 1940s-1970s) | Chicago School Era (c. 1970s-Present) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Concern | Market concentration and the power of large corporations. | Consumer welfare and economic efficiency. |

| View of Monopolies | Inherently suspect and likely to engage in anticompetitive conduct. | Often the result of superior efficiency; illegal only if maintained through exclusionary conduct. |

| Dominant Analytical Framework | Emphasis on “per se” rules and structural presumptions. | Emphasis on the “rule of reason” and case-specific economic analysis. |

| Burden of Proof | Lower for the government, especially in merger cases. | Higher for the government, requiring proof of anticompetitive effects and harm to consumers. |

Modern Strategic Challenges

Today, antitrust enforcers face a new set of strategic challenges in applying the first method to the digital economy. The rise of platform-based business models, network effects, and data-driven markets has complicated the traditional analysis of market power and competitive harm. For example, how should enforcers define the relevant market for a company like Google, which offers a wide range of interconnected services, many of them for free? Furthermore, the emergence of algorithmic collusion, where pricing algorithms learn to coordinate prices without any explicit human agreement, poses a profound challenge to the Sherman Act’s requirement of a “contract, combination, or conspiracy.” Enforcers must now develop new strategic approaches and analytical tools to detect and prosecute these novel forms of anticompetitive conduct, once again pushing the boundaries of the first method’s interpretation.

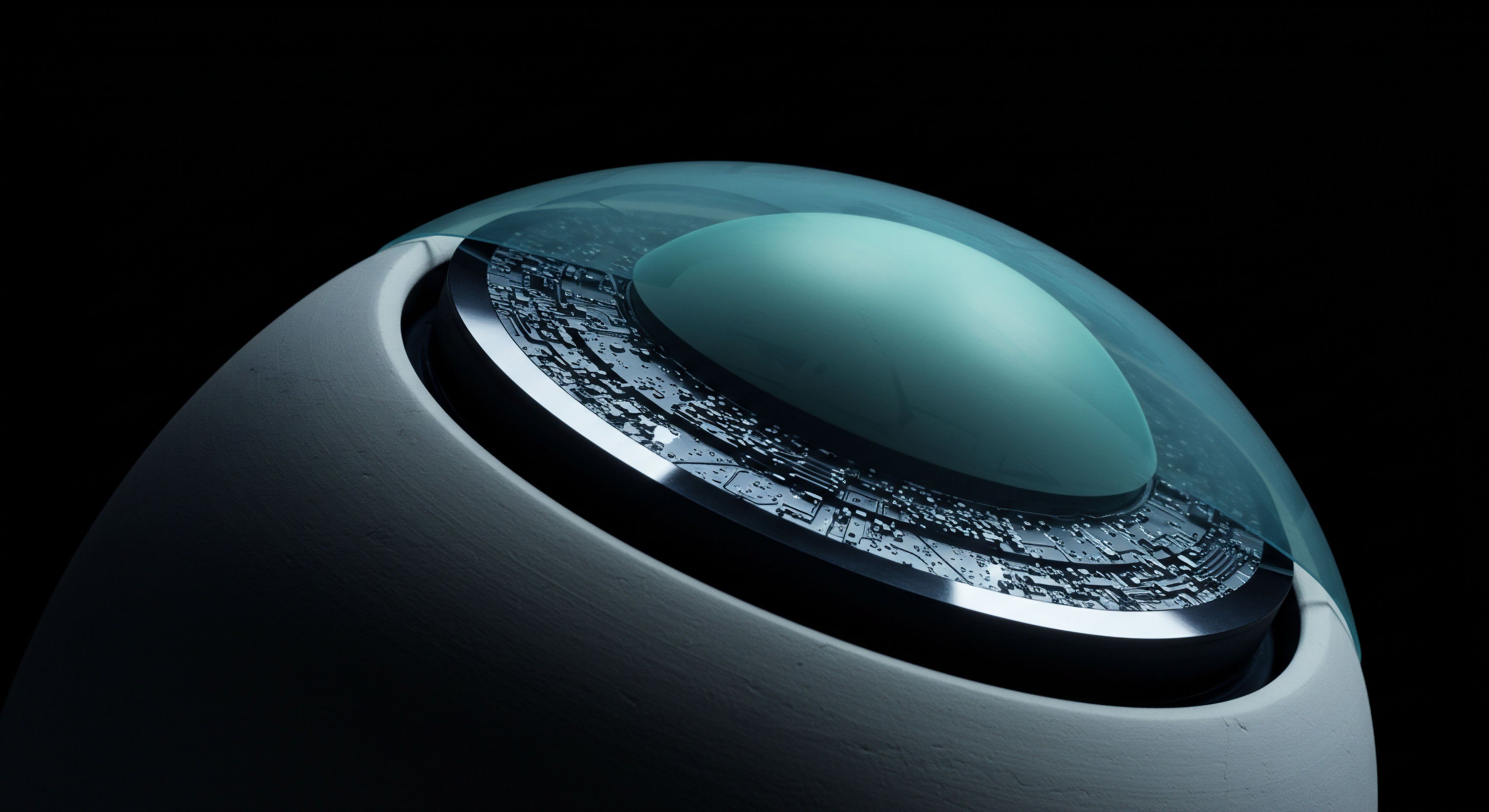

Execution

The execution of antitrust law in the United States is a complex process, shared primarily between two federal agencies ▴ the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). While the Sherman Act is a federal statute, its enforcement is not centralized in a single body. The DOJ has the authority to bring both civil and criminal enforcement actions under the Sherman Act, with criminal prosecutions typically reserved for “hard-core” per se violations like price-fixing.

The FTC, created in 1914, has the power to enforce the Clayton Act and the FTC Act, which prohibits “unfair methods of competition.” While the FTC cannot bring criminal charges, its administrative process allows for a more specialized and expert-driven approach to antitrust enforcement. This dual-enforcement system, while sometimes leading to overlapping jurisdiction, allows for a broader and more flexible application of antitrust principles.

The Anatomy of an Antitrust Investigation

An antitrust investigation is a meticulous and often lengthy process. It can be triggered by a variety of sources, including complaints from consumers or competitors, pre-merger notification filings, or the agencies’ own market monitoring. The initial phase involves a preliminary inquiry to determine if a full investigation is warranted. If so, the agency will issue subpoenas or Civil Investigative Demands (CIDs) to gather documents, data, and testimony from the companies involved.

This discovery phase can be incredibly extensive, involving the analysis of millions of documents and complex economic data. Economists play a critical role in this stage, helping to define the relevant market, assess market power, and model the potential anticompetitive effects of the conduct in question. If the investigation reveals evidence of a violation, the agency will decide whether to seek a settlement, file a lawsuit in federal court, or, in the case of the FTC, initiate an administrative proceeding.

The execution of antitrust law is a bifurcated and data-intensive process, relying on the combined efforts of lawyers and economists to translate legal theory into enforceable actions against anticompetitive conduct.

The following table outlines the typical stages of a federal antitrust investigation:

| Stage | Key Activities | Primary Actors |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Triggering Event | Receipt of complaints, pre-merger filings, or internal market analysis. | DOJ, FTC, consumers, businesses. |

| 2. Preliminary Inquiry | Initial assessment of the credibility and potential impact of the alleged violation. | Agency staff attorneys and economists. |

| 3. Formal Investigation | Issuance of subpoenas or CIDs for documents, data, and testimony. | Agency legal and economic teams. |

| 4. Analysis and Review | In-depth analysis of evidence, including market definition and competitive effects modeling. | Agency economists and legal staff. |

| 5. Enforcement Action | Decision to close the investigation, negotiate a settlement, or file a complaint in court. | Senior agency officials. |

Landmark Cases and Their Execution

The history of the Sherman Act’s execution is best understood through its landmark cases. These legal battles not only shaped the interpretation of the law but also demonstrated the immense challenges of its application.

- Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States (1911) ▴ This case resulted in the breakup of Standard Oil, but more importantly, it established the “rule of reason” as the primary standard for judging restraints of trade. The execution of this decision required a massive corporate restructuring, demonstrating the power of the courts to reshape entire industries.

- United States v. U.S. Steel (1920) ▴ In a significant victory for big business, the Supreme Court ruled that size alone is not an offense. This decision narrowed the scope of monopolization claims and raised the bar for proving illegal conduct, forcing enforcers to focus on anticompetitive actions rather than market structure.

- United States v. AT&T (1982) ▴ This case led to the consent decree that broke up the Bell System, a regulated monopoly. The execution was a monumental undertaking, requiring the divestiture of the regional Bell operating companies and fundamentally restructuring the telecommunications industry.

- United States v. Microsoft Corp. (2001) ▴ The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals found that Microsoft had illegally maintained its monopoly in the PC operating system market through exclusionary practices. While the government initially sought a structural remedy (a breakup), the final settlement focused on conduct remedies, requiring Microsoft to change its business practices. This case highlighted the challenges of applying antitrust law to the fast-moving technology sector.

References

- Twin, Alexandra. “Antitrust Laws ▴ What They Are, How They Work, Major Examples.” Investopedia, 1 May 2025.

- Islam, Aabis. “AI-Driven Antitrust and Competition Law ▴ Algorithmic Collusion, Self-Learning Pricing Tools, and Legal Challenges in the US and EU.” MarkTechPost, 10 August 2025.

- “Modern Antitrust Enforcement.” Yale School of Management, 2020.

- Abbott, Alden. “US Antitrust Laws ▴ A Primer.” Mercatus Center, 24 March 2021.

- “The Antitrust Laws.” Federal Trade Commission.

- “Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890).” National Archives.

- Bork, Robert H. The Antitrust Paradox ▴ A Policy at War with Itself. The Free Press, 1978.

- Hovenkamp, Herbert. The Antitrust Enterprise ▴ Principle and Execution. Harvard University Press, 2005.

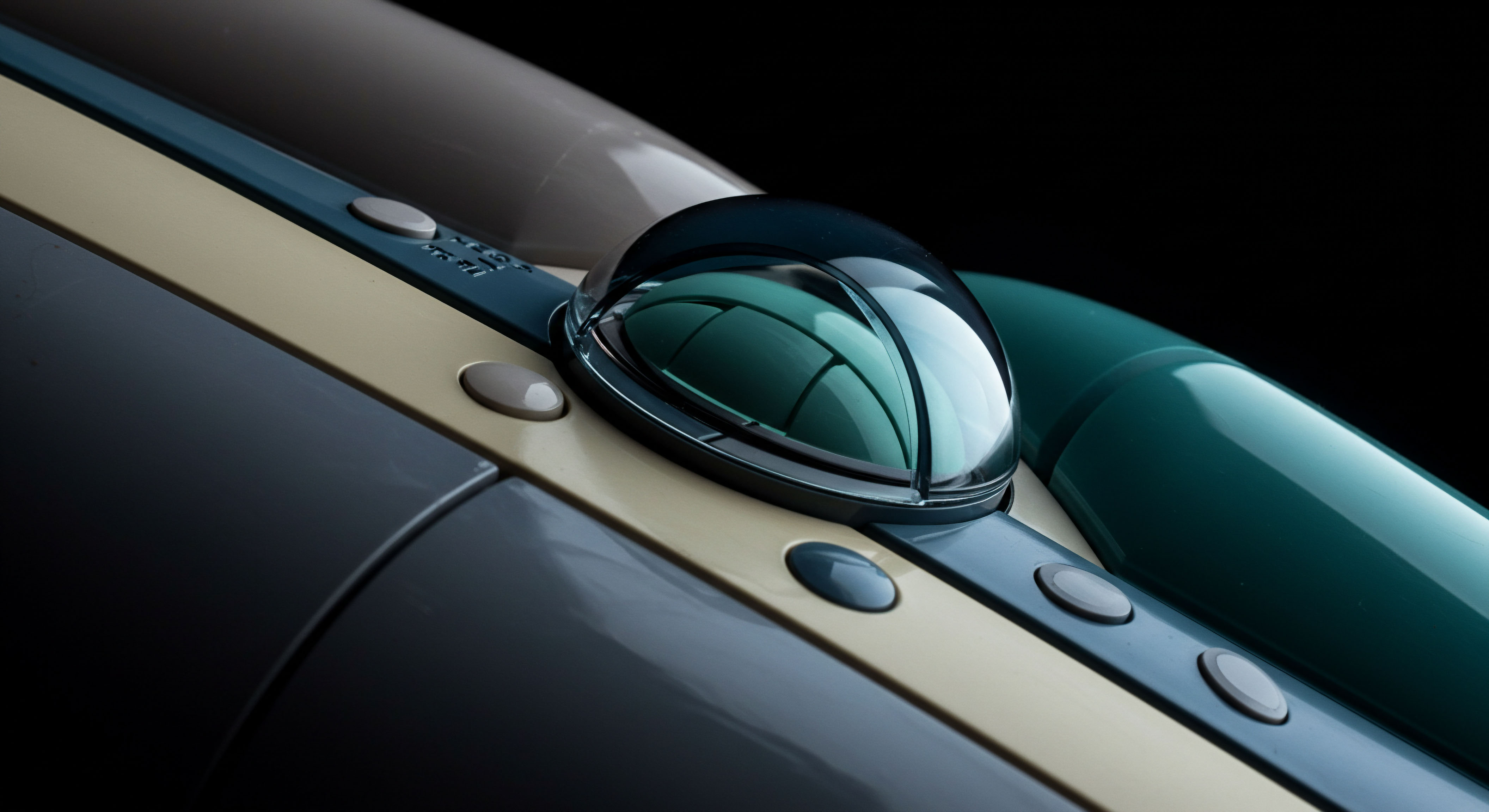

Reflection

The Enduring Questions of Competition

The legal odyssey of the Sherman Act reveals a fundamental truth ▴ the concept of fair competition is not static. It is a dynamic principle, constantly being redefined at the intersection of law, economics, and technology. The challenges faced by the first enforcers ▴ of giving meaning to ambiguous terms and applying them to a rapidly changing industrial landscape ▴ are not so different from the challenges faced by regulators today. The “first method” was not a final answer, but the beginning of a conversation that continues to this day.

As we confront the complexities of digital markets, artificial intelligence, and globalized commerce, the core questions posed by the Sherman Act remain as relevant as ever. How do we preserve the benefits of scale and innovation while preventing the abuse of market power? How do we distinguish between aggressive competition and exclusionary conduct? The answers to these questions will continue to evolve, but the framework for asking them was forged in the legal crucible of the first method.

Glossary

Sherman Antitrust Act

United States

First Method

Sherman Act

Antitrust Enforcement

Algorithmic Collusion

Antitrust Law