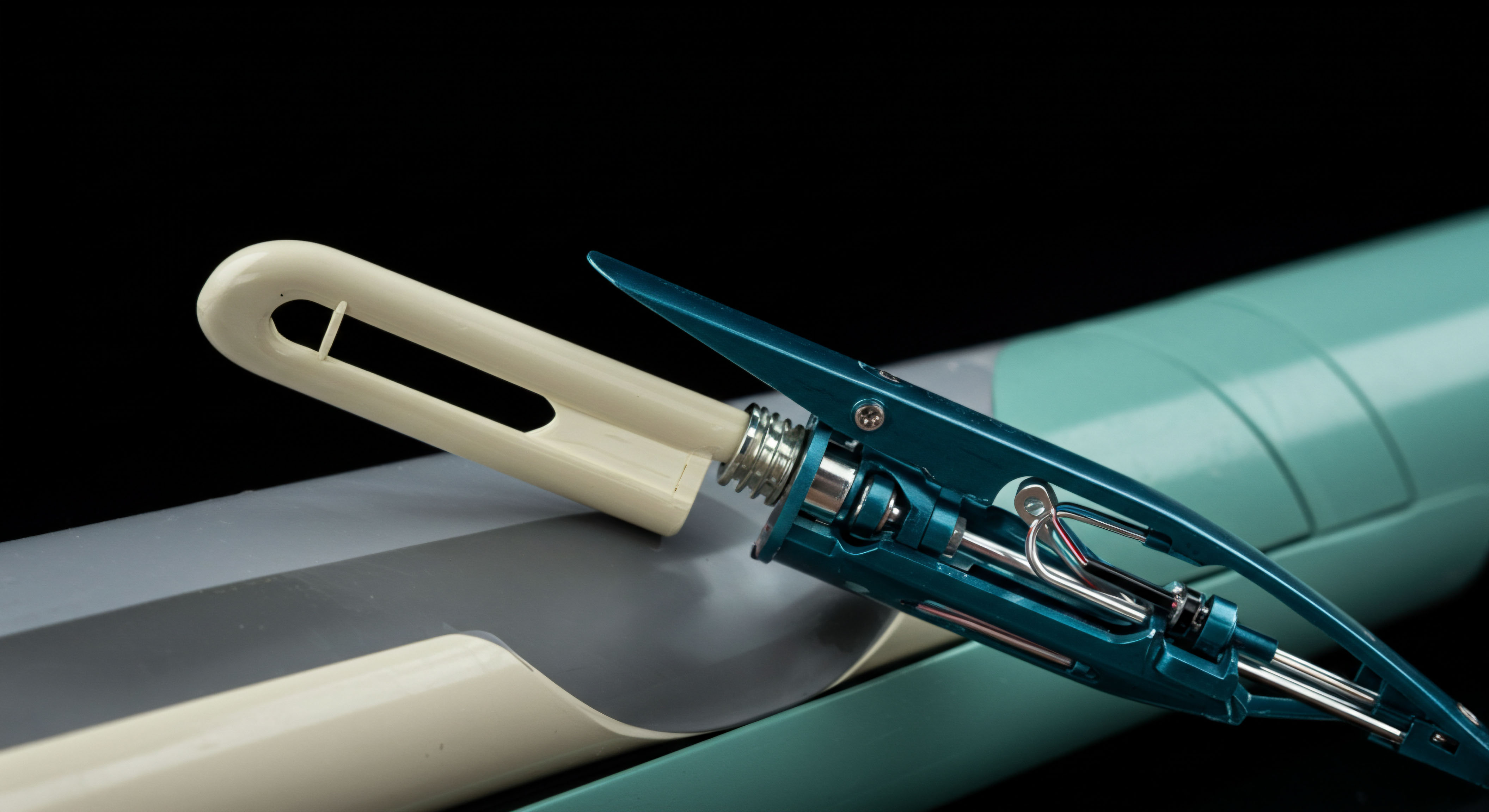

Concept

The architecture of modern financial markets rests on a series of carefully engineered safeguards designed to contain failures before they become systemic contagions. Central Counterparty Clearing Houses (CCPs) represent the core of this architecture, acting as the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. Within this framework, the Cover-2 standard is a foundational risk management protocol. It is a pre-calculated, rules-based answer to a severe, yet plausible, crisis scenario ▴ the simultaneous failure of the two largest clearing members.

Its function is to ensure the CCP has sufficient pre-funded financial resources to absorb the credit losses stemming from these two defaults under extreme market stress. This standard dictates the minimum size of the CCP’s default fund, a mutualized pool of capital contributed by all clearing members.

Understanding the Cover-2 standard requires viewing the CCP not as a simple intermediary, but as a systemic shock absorber. When a member defaults, the CCP is legally obligated to fulfill that member’s obligations to the market. This process begins with the seizure and liquidation of the defaulting member’s initial margin, which is the collateral posted to cover potential losses under normal market conditions. The default fund, sized according to the Cover-2 standard, represents the next critical layer of defense.

It is a mutualized resource designed to handle losses that exceed the defaulter’s own collateral, thereby protecting the CCP itself and the non-defaulting members from the immediate fallout. The standard is calibrated against “extreme but plausible” market scenarios, a term that encompasses severe price shocks and liquidity dislocations derived from historical crises and forward-looking hypothetical events.

The Cover-2 standard is a critical risk management protocol that requires a Central Counterparty (CCP) to hold sufficient financial resources to withstand the simultaneous default of its two largest clearing members under extreme market conditions.

The implementation of this standard is a deliberate engineering choice. It directly addresses the concentration risk inherent in centrally cleared markets, where a small number of large members often account for a significant portion of total market activity. By preparing for the failure of the two largest participants, the CCP establishes a firewall capable of containing a highly disruptive event. This pre-funded certainty is what allows the rest of the market to continue operating with confidence, even in the face of a significant member failure.

The protocol transforms a potential cascading failure into a manageable, albeit serious, operational event for the CCP. It is a clear articulation of the CCP’s capacity to absorb a defined level of stress, providing transparency and predictability to all market participants.

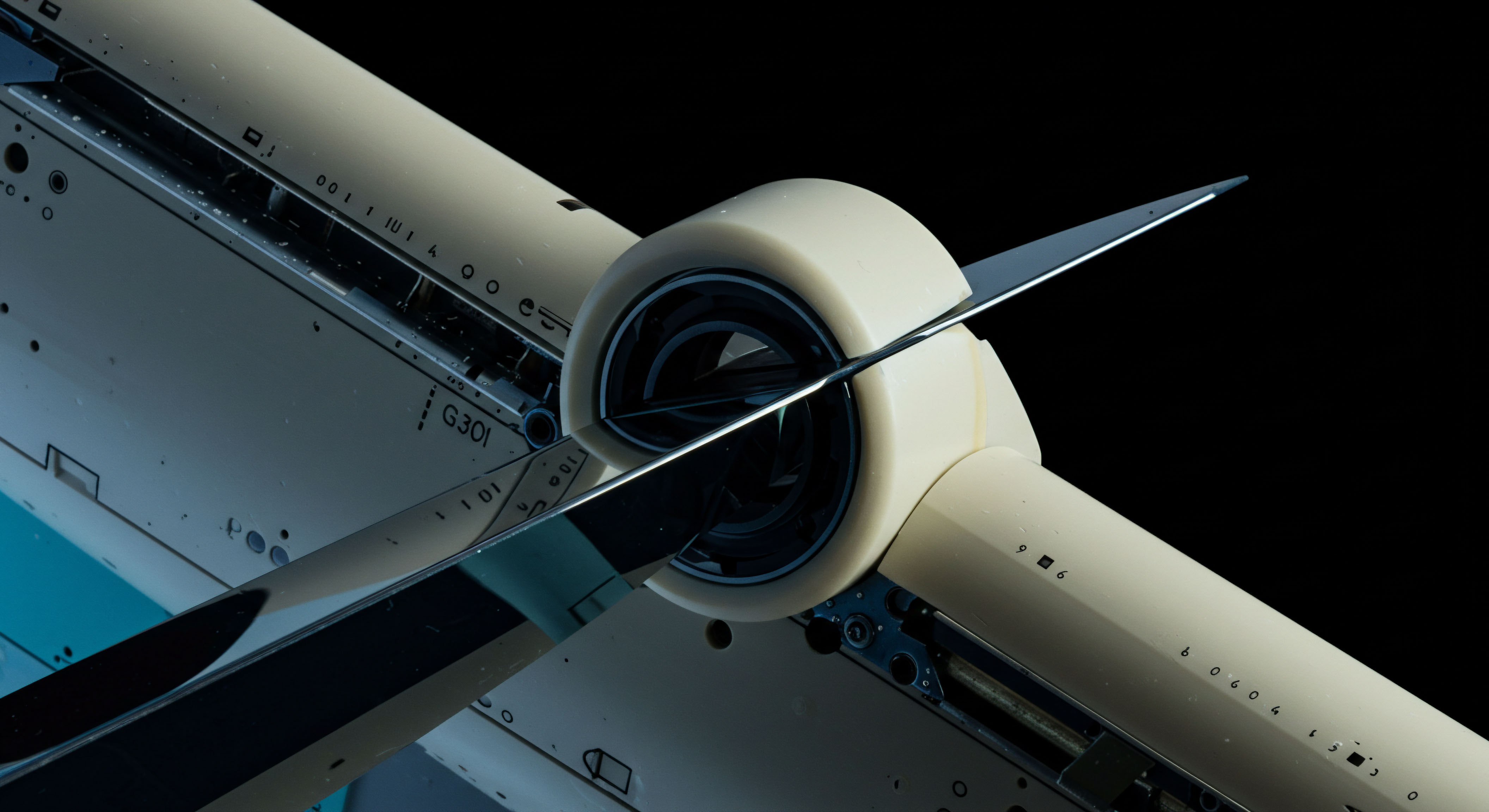

Strategy

The strategic selection of the Cover-2 standard as a global norm for CCPs reflects a carefully calibrated balance between systemic safety and capital efficiency. A CCP’s risk management strategy is a multi-layered defense system, and the default fund is a critical component of this “default waterfall.” The decision to size this fund to cover the simultaneous default of the two largest members is a strategic response to the nature of risk in modern financial networks. It acknowledges that the greatest systemic threat often comes from the failure of a highly interconnected, major participant, and that in a true crisis, failures are rarely isolated events. The default of one major firm can trigger liquidity and solvency issues at another, making a two-member failure a prudent scenario to model.

Why Not Cover 1 or Cover 3?

The choice of “two” is a strategic trade-off. A “Cover-1” standard, while less costly for members who must contribute to the default fund, could be perceived as insufficient. A single major default, especially if it occurs in conjunction with broader market turmoil, might exhaust a Cover-1 fund and force the CCP to use its own capital or, in a worst-case scenario, allocate losses among surviving members. This could undermine market confidence precisely when it is most needed.

Conversely, a “Cover-3” or higher standard would offer a greater degree of protection but at a significant cost. It would require clearing members to post substantially more capital to the default fund, capital that would be idle in non-crisis periods. This increased cost could deter participation in central clearing, concentrate activity among fewer, larger players, or make hedging prohibitively expensive, thereby creating new forms of systemic risk.

The strategic adoption of Cover-2 balances the need for robust protection against systemic contagion with the imperative of maintaining capital efficiency for clearing members.

The Cover-2 standard, therefore, represents a strategic equilibrium. It provides a robust buffer that is widely considered sufficient to handle most severe, multi-actor default scenarios without imposing an excessive financial burden on the market as a whole. This equilibrium builds confidence, which is the ultimate currency of any financial market. It assures participants that the clearinghouse is resilient enough to withstand a significant shock, which in turn encourages greater use of central clearing, enhancing market transparency and reducing bilateral counterparty risk across the system.

The Strategic Implications of Mutualization

The default fund is a mutualized resource, meaning the losses of a failed member are borne, in part, by its surviving competitors. This structure has profound strategic implications. It creates a powerful incentive for members to monitor the risk-taking activities of their peers. Since every member’s contribution to the default fund is at risk if another member fails, there is a collective interest in maintaining high standards of risk management across the entire clearing member community.

This peer-monitoring effect is a crucial, albeit informal, layer of the CCP’s risk management framework. The table below illustrates the strategic trade-offs between different coverage levels.

| Coverage Standard | Systemic Safety Level | Capital Efficiency for Members | Strategic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cover 1 | Lower | Higher | May be insufficient to stop contagion in a major crisis, potentially undermining confidence in the CCP. |

| Cover 2 | High | Medium | Represents the industry consensus, balancing robust protection with manageable costs, fostering strong market confidence. |

| Cover 3+ | Very High | Lower | Could make central clearing prohibitively expensive, potentially driving risk into less transparent bilateral markets. |

Furthermore, the Cover-2 standard forces a CCP and its members to engage in rigorous and continuous stress testing. To properly size the default fund, the CCP must constantly model the potential losses that would result from the failure of its two largest members under a wide range of extreme but plausible scenarios. This process is not static.

As market positions change, the identity of the two largest members and their potential loss profiles evolve. The discipline of maintaining the Cover-2 standard ensures that the CCP has a dynamic and forward-looking view of its largest exposures, which is a critical strategic advantage in managing systemic risk.

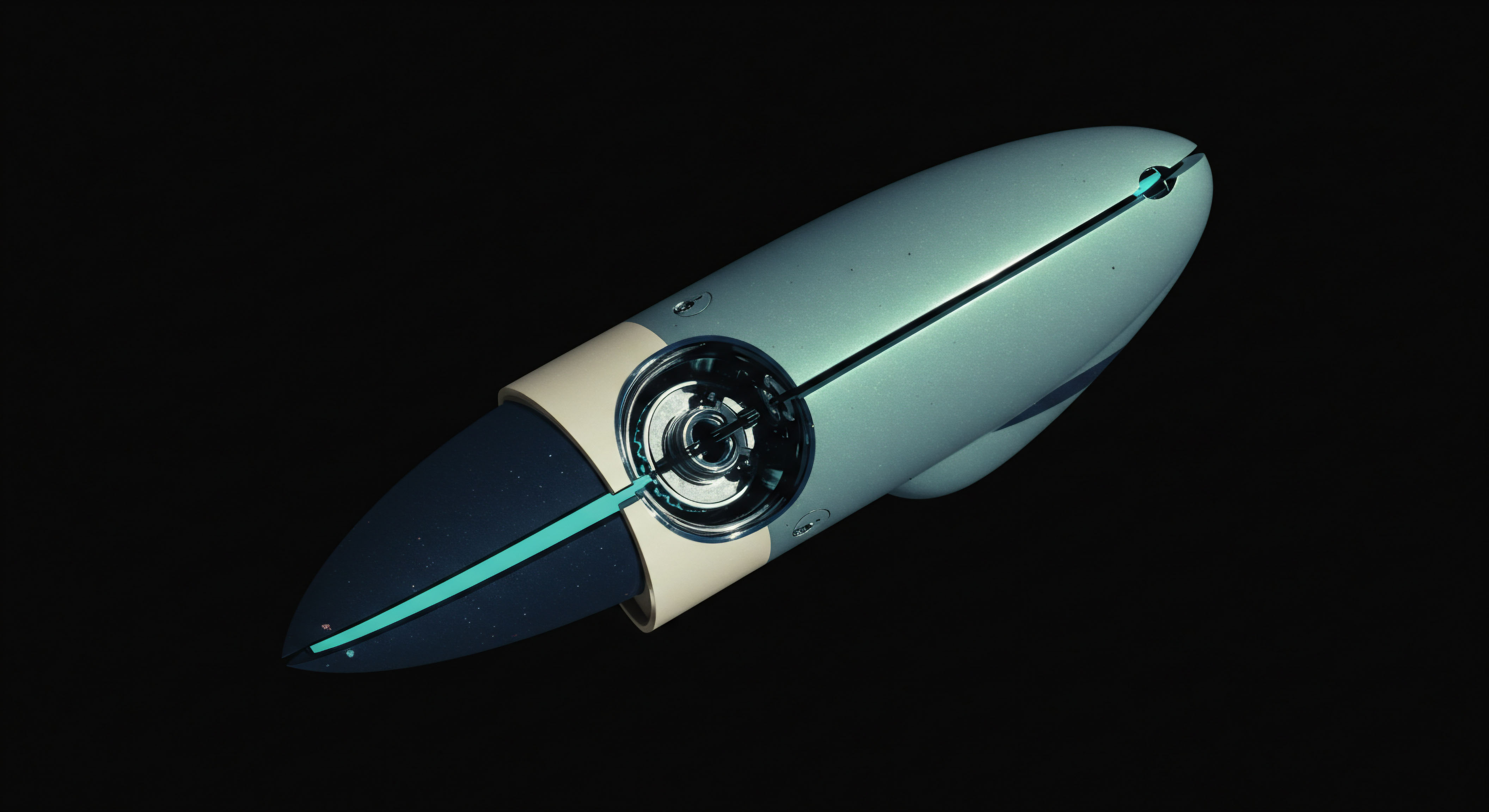

Execution

The execution of the Cover-2 standard moves from a strategic principle to a precise operational protocol during a member default. When a clearing member fails to meet its obligations, the CCP initiates a formal default management process. This process is a pre-defined sequence of actions designed to isolate the failure, neutralize the risk of the defaulter’s portfolio, and protect the CCP and its surviving members.

The Cover-2 standard defines the quantum of one of the most critical resources available in this process ▴ the default fund. The execution is a high-stakes, time-sensitive operation that relies on the clear rules and pre-funded resources established by the risk management framework.

The Default Waterfall an Operational Checklist

The CCP’s response to a member default follows a cascading sequence of steps, often referred to as the “default waterfall.” Each step utilizes a different layer of financial resources to absorb losses. The process is designed to be sequential and predictable. The following list outlines the typical operational execution of a default waterfall in a CCP that adheres to the Cover-2 standard.

- Declaration of Default The CCP’s risk committee, upon confirmation that a member cannot meet its obligations, formally declares a default. This triggers the immediate isolation of the defaulting member’s accounts and positions.

- Use of Defaulter’s Resources The first line of defense is always the capital posted by the defaulting member. The CCP will immediately utilize the entirety of the defaulter’s initial margin and any other collateral held.

- CCP Hedging and Portfolio Auction The CCP takes control of the defaulter’s open positions. Its primary goal is to neutralize the market risk of this portfolio. This is often achieved through hedging trades in the open market. Subsequently, the CCP will attempt to auction the portfolio (or segments of it) to other clearing members. The goal is to transfer the positions to solvent firms in an orderly manner.

- Application of the Default Fund If the losses from liquidating the defaulter’s portfolio exceed the defaulter’s own resources, the CCP will draw upon the default fund. This is where the Cover-2 sizing becomes critical. The CCP will use contributions from the default fund to cover the remaining losses. The process begins with the CCP’s own contribution to the fund (“skin-in-the-game”) and is followed by the pro-rata use of contributions from all surviving clearing members.

- Loss Allocation to Surviving Members In the extremely unlikely event that the default of two large members generates losses that completely exhaust the default fund, the CCP may have the power to call for additional contributions from surviving members, up to a pre-agreed limit. This is a final, unfunded layer of the waterfall.

Quantitative Modeling a Cover-2 Stress Test Scenario

To understand the execution in practice, consider a hypothetical stress test for a CCP. The CCP has 20 clearing members. Its default fund is sized to the Cover-2 standard based on regular stress testing. The table below shows a simplified view of the CCP’s pre-funded resources before the stress event.

| Resource Layer | Description | Amount (USD Millions) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Margin (IM) | Total margin posted by all members against their positions. | $25,000 |

| Default Fund Contribution (CCP) | The CCP’s own capital contributed to the default fund (“skin-in-the-game”). | $500 |

| Default Fund Contribution (Members) | Total mutualized contributions from all 20 clearing members. | $5,000 |

| Total Prefunded Resources | Sum of all pre-funded resources available to the CCP. | $30,500 |

Now, imagine a severe market shock occurs. Two of the largest clearing members, Firm A and Firm B, default simultaneously. The CCP’s stress test had previously identified these two firms as creating the largest potential loss under this specific scenario. The execution of the default management process unfolds as follows:

- Firm A Default The close-out of Firm A’s portfolio results in a total loss of $3.2 billion. The CCP seizes Firm A’s initial margin of $2.5 billion. This leaves a residual loss of $700 million.

- Firm B Default The close-out of Firm B’s portfolio results in a total loss of $4.0 billion. The CCP seizes Firm B’s initial margin of $3.0 billion. This leaves a residual loss of $1.0 billion.

- Total Residual Loss The combined loss exceeding the defaulters’ own collateral is $700 million + $1.0 billion = $1.7 billion.

- Default Fund Application The CCP must now cover this $1.7 billion shortfall. It first applies its own $500 million contribution from the default fund. The remaining loss is now $1.2 billion. This amount is then drawn, pro-rata, from the $5.0 billion in contributions made by the 18 surviving members. Since the required $1.2 billion is well within the available $5.0 billion, the default is fully contained. The CCP remains solvent, and the market continues to function. This successful execution validates the strategic choice of the Cover-2 standard.

This scenario demonstrates the mechanical, rules-based nature of the Cover-2 execution. It is a pre-planned, quantitatively-grounded process designed to remove discretion and uncertainty in a crisis. The standard ensures that the necessary resources are not only available but are deployed in a predictable sequence, providing a critical anchor of stability for the entire financial system.

References

- Bank of England. “Supervisory Stress Testing of Central Counterparties.” 21 June 2021.

- “The Bank of England on CCP default funds ▴ is ‘cover 2’ enough?” Finadium, 27 Oct. 2014.

- LSEG. “Best practices in CCP risk management.” Accessed 5 Aug. 2025.

- Haene, Philipp, and Gábor Fukker. “Systemic Risk in Markets with Multiple Central Counterparties.” Swiss National Bank, Working Papers, 2022-11-21.

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures & International Organization of Securities Commissions. “Resilience of central counterparties (CCPs) ▴ Further guidance on the PFMI.” Bank for International Settlements, July 2017.

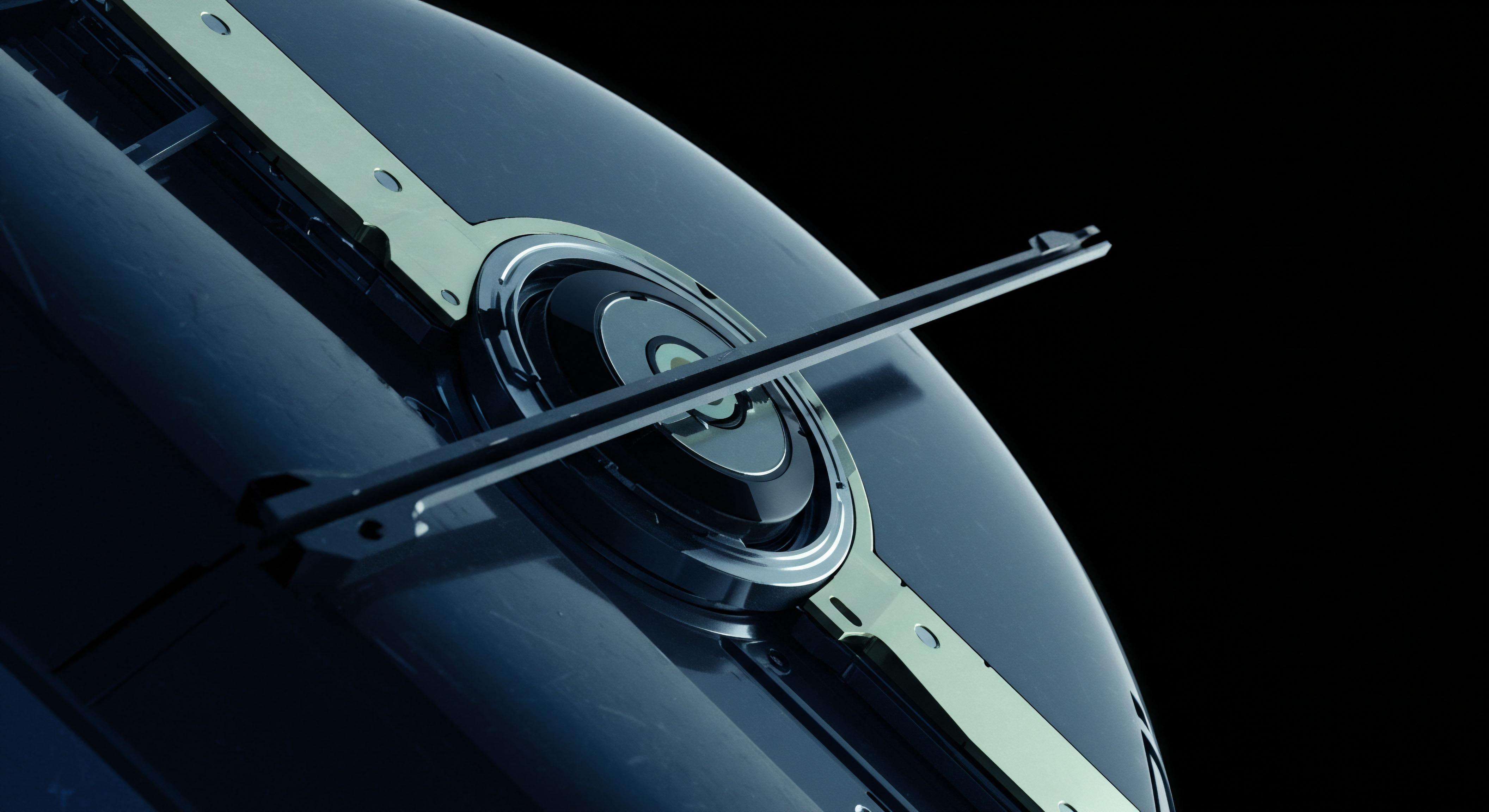

Reflection

The mechanical precision of the Cover-2 standard provides a robust defense against predictable crises. Its successful execution in a stress scenario is a testament to a well-designed system. Yet, the architecture of risk management is never static.

How does this specific component, the Cover-2 standard, integrate with your own firm’s internal model of counterparty and liquidity risk? Viewing the CCP’s default waterfall as an extension of your own risk framework offers a more complete picture of your true exposures.

Does Your Framework Account for Waterfall Depletion?

The successful absorption of a Cover-2 event by a CCP is the expected outcome. A more severe event, however, could begin to deplete the resources of surviving members through loss allocation mechanisms. Acknowledging this possibility, however remote, requires a deeper level of strategic planning.

The knowledge of the system’s design is the first step. The ultimate advantage lies in integrating that knowledge into a holistic, firm-specific view of systemic risk, transforming a public safeguard into a component of your private operational intelligence.

Glossary

Central Counterparty Clearing

Cover-2 Standard

Clearing Members

Default Fund

Initial Margin

Capital Efficiency

Default Waterfall

Surviving Members

Systemic Risk

Risk Management